There is an index of my blogs at the foot of this page. Click on “Mark’s page” above to find separate pages which contain my blogs for each month from January 2017 to September 2019.

Ministry of Flat Walks 34: Haverthwaite to Greenodd (and Rounsea Wood)

14th June 2022

There were a couple of unusual features of this Ministry of Flat Walks episode. Firstly, it is in part a repeat of a previous entry, although from some time ago – see MoFW No 2 from 2017. However the best part (Roudsea Wood) is new. Secondly, Mark was on the train when we did this walk, on his way back to London.

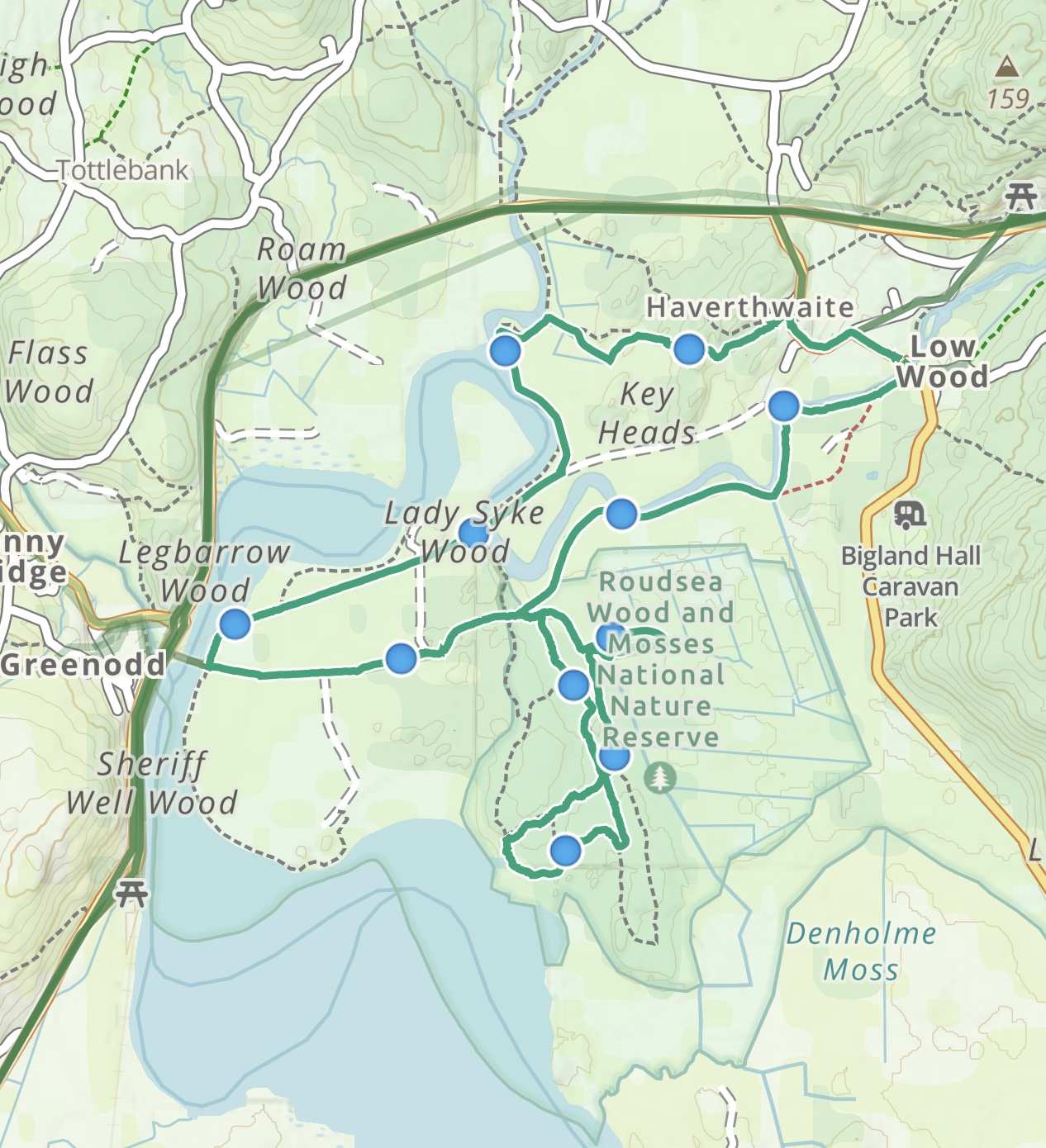

Clearly the personnel were different therefore. John and David (!) left the car at Low Wood and walked from there to Haverthwaite, as shown on this map (courtesy <gaiagps.com>).

The first part was along the road to Haverthwaite villlage, then down a small and very overgrown path to the fields west of the village itself. Much mud, thistles and nettles. We joined the old railway track between Haverthwaite and Greenodd just before Lady Syke cottages and then followed the trackbed to the place where the railway used to cross the estuary. We then walked up an unsealed road towards Roudsea Wood.

The first part was along the road to Haverthwaite villlage, then down a small and very overgrown path to the fields west of the village itself. Much mud, thistles and nettles. We joined the old railway track between Haverthwaite and Greenodd just before Lady Syke cottages and then followed the trackbed to the place where the railway used to cross the estuary. We then walked up an unsealed road towards Roudsea Wood.

Roudsea wood is currently known amongst the ornithological community as a site for ospreys to breed. There were none of these sea-eagles in sight however, perhaps also explaining the complete absence of “twitchers”.

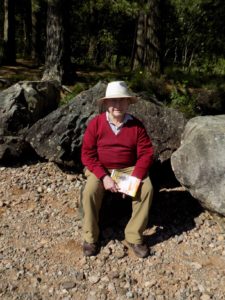

The woods themselves are very beautiful, however.

The woods themselves are very beautiful, however.

John tells me that there used to be a tramway through these woods carrying gunpowder from the Low Woods factory to a pier on the estuary, but we saw no trace of this.

Unless, that is, this well-formed track is the old railway. There is a large derelict shed near the water which apparently is the old gunpowder store.

Whatever minor historical charms the wood might or might not have, it is a lovely walk in the late afternoon, and much recommended.

Mark or no-Mark it is a very pleasant way to spend two to three hours just a very short drive from Cark.

Ministry of Flat Walks 33: Ravenglass and Drigg

12 August 2021

To follow this walk, open another tab in your browser and input this web address: https://bit.ly/3yDNfjH. You will need to scroll the map a little to the north to see the full extent of the route.

This is not an outstanding walk for beauty or interest of the landscape, and it involves quite a lot of road walking, though (with one exception) the roads are almost empty of traffic. But it has two strong virtues. It is very flat: I estimate that it climbs barely more than 25 metres, over a length of 5-6 miles. And along the way, at least at the right time of year, you should see a wide variety of butterflies. John spotted and photographed nine different types, and I dare say there were several more that fled from his lens, as they so often do.

The walks starts in Ravenglass where there is a public pay-and-display car park as well as free parking on the sea front. There is also a public convenience next to the car park. Walk down to the sea front and back from there towards the main line railway bridge. On the seaward side of the bridge, turn to the left and along the footpath which crosses a pedestrian bridge, parallel to the railway, over the River Mite. The mud flats here are covered at high tide, and the view of Ravenglass is most picturesque at that time.

On the far side of the bridge, the path turns left and follows the shoreline for a quarter mile or so until you come to the few buildings in the village – hamlet, really – of Saltcoats. Permanent buildings, that is. On your left, as you turn inland along the road at Saltcoats, is a caravan site occupied by dozens of pale green caravans. I remember seeing these from the train and thinking it must be a bleak place to live.

On the far side of the bridge, the path turns left and follows the shoreline for a quarter mile or so until you come to the few buildings in the village – hamlet, really – of Saltcoats. Permanent buildings, that is. On your left, as you turn inland along the road at Saltcoats, is a caravan site occupied by dozens of pale green caravans. I remember seeing these from the train and thinking it must be a bleak place to live.

You can’t miss your way in Saltcoats as there is only one road, but just past the few buildings is a road junction, where the signs for the cycle route point away to your left. That is the long way round. You should carry straight on and soon enough you will come to the reason for the cyclists’ diversion: Saltcoats Crossing, a manually-operated level crossing over the railway. This is closed to road traffic except on request, but there are pedestrian gates which you can use to cross the line. Neither the road nor the railway is busy, and I feel a bit sorry for the crossing operator who is now based in a Portakabin-type hut on the seaward side of the crossing: he must have a lonely time. On the other side is a building which I think must at one time have been the combined signalbox and dwelling, but it has long since been sold off to be someone’s home.

You can’t miss your way in Saltcoats as there is only one road, but just past the few buildings is a road junction, where the signs for the cycle route point away to your left. That is the long way round. You should carry straight on and soon enough you will come to the reason for the cyclists’ diversion: Saltcoats Crossing, a manually-operated level crossing over the railway. This is closed to road traffic except on request, but there are pedestrian gates which you can use to cross the line. Neither the road nor the railway is busy, and I feel a bit sorry for the crossing operator who is now based in a Portakabin-type hut on the seaward side of the crossing: he must have a lonely time. On the other side is a building which I think must at one time have been the combined signalbox and dwelling, but it has long since been sold off to be someone’s home.

Cross the railway and continue along the road for another quarter mile or so. You should notice two driveways off to your right which lead to houses well back from the road. Just after the second of these is a track leading to the left. There is no signpost, but you really can’t miss it: the track is dead straight, with hedges to either side, and wide enough for a tractor to pass along. Turn on to this track and continue for half a mile or so until you meet the road at the far end.

It was here, in the hedges and borders on either side of the track, that we spotted most of the butterflies, so many of them that I had considerable difficulty in keeping John moving. There are also many wildflowers, including several of varieties unfamiliar to me, though I am no expert. If you have a naturalist in your party, prepare to be delayed.

It was here, in the hedges and borders on either side of the track, that we spotted most of the butterflies, so many of them that I had considerable difficulty in keeping John moving. There are also many wildflowers, including several of varieties unfamiliar to me, though I am no expert. If you have a naturalist in your party, prepare to be delayed.

When you reach the road, turn right – but, before you do, glance left, and you will see that the railway crosses over this road on a bridge. That is why the cyclists are sent by this route: they can cross under the railway without needing to rouse the crossing keeper from his Portakabin.

Now continue along the road. After a quarter mile or so, at the first bend, a lane leads off to the left. Here there is a sign showing that the lane leads to Holmrook. Turn along this lane, which ruins briefly straight and then round a series of bends up to a gate. The River Irt is just to your left, but cannot be seen yet. Go through the gate and into the field beyond. There is no visible path, but if you carry straight on, just to the right of a group of trees, you will come suddenly to a flight of steps down a steep bank towards Holme Bridge, an ancient packhorse bridge with a steep arch across the river.

Cross the bridge and enter a broad meadow. Here is another signpost – Drigg Church to the left, Holmrook to the right. Take the left hand route and follow a path that has been worn through the grass up the side of the meadow, a very gentle climb. After a couple of hundred yards the path bends a little to the left and becomes a worn track suitable for farm vehicles which continues up to the village of Drigg.

Cross the bridge and enter a broad meadow. Here is another signpost – Drigg Church to the left, Holmrook to the right. Take the left hand route and follow a path that has been worn through the grass up the side of the meadow, a very gentle climb. After a couple of hundred yards the path bends a little to the left and becomes a worn track suitable for farm vehicles which continues up to the village of Drigg.

Turn right here on to the road. This is the one part of the walk where you will encounter some traffic. But there is a pavement on one side or the other from here all the way to Holmrook, not quite half a mile, where you meet the A595 coast road from Barrow to Whitehaven. Turn right here, past a row of houses on your right, with on your left a low wall protecting the bank of the River Irt. The road soon takes a sharp left turn across a modern bridge. Just before you cross the bridge there is a narrow gap in the wall on your right and a sign marking a path that leads back to Holme Bridge.

Take this path, which follows the river bank. The line of the path is quite clear and fairly well worn, but the undergrowth rises high on both sides and it is often difficult to see anything of the river: it is only a few feet to your left, but several feet lower than the path.

Take this path, which follows the river bank. The line of the path is quite clear and fairly well worn, but the undergrowth rises high on both sides and it is often difficult to see anything of the river: it is only a few feet to your left, but several feet lower than the path.

Eventually you will arrive back at Holme Bridge. Cross the bridge and turn left, following a worn path which after a few yards turns right and enters a large field. At this point the path disappears, but you should be able to see and head for a gate in the hedge on the far side. After you pass through this gate the path reappears; follow it along the edge of the next field until it turns right down a short lane and through a gate into a road. Turn right here and walk straight along the road, across Saltcoats Crossing and over the River Mite bridge back to Ravenglass.

John and I found the final section of this walk rather tiresome as we were simply retracing our steps, which I generally prefer not to have to do. If we were to try this walk again I think we might do it in one direction only, leaving the car at Ravenglass, catching a train to Drigg and walking back; or possibly the other way round. There is quite a lot of road walking and not enough of interest to compensate for doing it twice.

But the route itself is quite interesting for the level crossing, the packhorse bridge, the rivers and the butterflies. Recommended, with reservations.

Thanks as always to John for the photographs.

——————–

Northern Lakes, again

8 July 2021

John and I are up in Cark for a week, though John is working this morning (Thursday). Such are the benefits of Microsoft Teams – he can interrupt his week’s holiday for a training session. Oh well.

Anyway, this is an ideal time for longer trips, as it is midweek during school term, so places of interest are less likely to be crowded. Three years ago I posted a blog about a trip John and I made round some of the Lake District’s northern lakes. Yesterday we made a similar trip, visiting a couple of lakes we had previously missed.

We started by driving north to Keswick, where John wanted to see Castlerigg stone circle. The journey was not quite uneventful. One effect of Covid has been that even more people than usual are visiting the Lakes, including many newcomers, and some of them clearly have only a hazy idea about how to drive safely even along the main roads, which are often twisty, sometimes narrow and in places quite steep. We were caught a couple of times behind drivers who were suffering from exaggerated caution, and once behind a large coach which was trying to negotiate the tricky section between Skelwith Bridge and Ambleside. John, our usual driver, gets very frustrated when he is forced to drive slower – quite often a good deal slower – than he thinks necessary or safe. Of course he and I have the benefit of knowing the roads at least moderately well. Still, it was probably quite a good thing that I needed a short break at Grasmere while John could recover his composure.

Castlerigg is located on the summit of a hill east of Keswick with splendid views of Blencathra to the north and the central Lakes fells to the south. It is not of course as imposing a monument as Stonehenge, but the location is spectacular and the circle of stones is pretty much complete. No-one really knows why it was built – as a market, a meeting place, a religious site? – but the ancients at least had a good eye for location. An enthusiastic party of 6-7 year olds (my estimate) was just leaving as we arrived, much to John’s relief: they would have spoiled his photography completely, though there were still plenty of visitors and it wasn’t possible to avoid them all.

Castlerigg is located on the summit of a hill east of Keswick with splendid views of Blencathra to the north and the central Lakes fells to the south. It is not of course as imposing a monument as Stonehenge, but the location is spectacular and the circle of stones is pretty much complete. No-one really knows why it was built – as a market, a meeting place, a religious site? – but the ancients at least had a good eye for location. An enthusiastic party of 6-7 year olds (my estimate) was just leaving as we arrived, much to John’s relief: they would have spoiled his photography completely, though there were still plenty of visitors and it wasn’t possible to avoid them all.

From Castlerigg we drove on, avoiding Keswick town centre, and along the road that runs parallel to but some distance from the east side of Bassenthwaite Lake. We tried to find a place we could stop and walk down to the shoreline, but after a couple of failed attempts decided to drive on to the foot of the lake where the River Derwent flows out northwards towards Cockermouth and the sea. There are a couple of car parks marked on the map here adjacent to the lake, but both were already full when we arrived. Instead we parked on a grass verge just by the bridge over the Derwent and walked a couple of hundred yards down to the lake.

Mum used to say that Bassenthwaite was a dull lake, and we always used to take her at her word. On the rare occasions that we ventured into the northern Lakes it was usually to Keswick or Derwent Water or Buttermere, all of which are of course well worth visiting. But John expressed a wish to see Bassenthwaite. So here we were, and I was very pleasantly surprised. The lake is obviously less grand than Wast Water or Coniston but it is still very beautiful and remarkably quiet – though at our picnic spot we were amused by the antics of an enthusiastic golden retriever splashing in the shallows with its owners. I have read that Bassenthwaite is noted for having warmer waters than other lakes, and I can believe it.

Mum used to say that Bassenthwaite was a dull lake, and we always used to take her at her word. On the rare occasions that we ventured into the northern Lakes it was usually to Keswick or Derwent Water or Buttermere, all of which are of course well worth visiting. But John expressed a wish to see Bassenthwaite. So here we were, and I was very pleasantly surprised. The lake is obviously less grand than Wast Water or Coniston but it is still very beautiful and remarkably quiet – though at our picnic spot we were amused by the antics of an enthusiastic golden retriever splashing in the shallows with its owners. I have read that Bassenthwaite is noted for having warmer waters than other lakes, and I can believe it.

After lunch we drove on across the northern moors to Loweswater, which Mum used to say was one of her favourite lakes. Our plan had been to walk round the lake, which we have never done, to add another to my Ministry of Flat Walks. But my sore knee from the previous day’s excursion ruled that out, so we just walked along the shoreline a short way for John to take some pictures.

After lunch we drove on across the northern moors to Loweswater, which Mum used to say was one of her favourite lakes. Our plan had been to walk round the lake, which we have never done, to add another to my Ministry of Flat Walks. But my sore knee from the previous day’s excursion ruled that out, so we just walked along the shoreline a short way for John to take some pictures.

And finally on to Ennerdale. It must be twenty years since I was last there, and my memories of that visit are pretty hazy. Actually what I remember most of that visit is the traces we observed of the old mineral railways that once ran across these fells, allowing iron ore, coal and slate to be carried down from the mines to the main line at Egremont and Cleator Moor, and the port at Whitehaven. My image of Ennerdale itself was of a large empty lake surrounded by trees.

Well, the trees are still there, but a lot has been done to make Ennerdale Water a more attractive spot for the determined traveller. The approach road is still long and narrow, but it has clearly been well resurfaced within the last couple of years: presumably the contribution of Cumbria County Council to the Wild Ennerdale partnership that also involves Forestry England*, Natural England*, the National Trust (all of which own parts of the surrounding countryside) and the utility company United Utilities. There is a website: http://www.wildennerdale.co.uk.

Well, the trees are still there, but a lot has been done to make Ennerdale Water a more attractive spot for the determined traveller. The approach road is still long and narrow, but it has clearly been well resurfaced within the last couple of years: presumably the contribution of Cumbria County Council to the Wild Ennerdale partnership that also involves Forestry England*, Natural England*, the National Trust (all of which own parts of the surrounding countryside) and the utility company United Utilities. There is a website: http://www.wildennerdale.co.uk.

Among other things, the partnership has created a new car park at the end of the approach road and posted several notices explaining what can be seen at Ennerdale, including a colony of red squirrels and the rare marsh fritillary butterfly. Sadly we did not manage to spot either of these while we were there, though John did chase after several other butterflies in hope.

It looks as if the partners have also upgraded the footpath round the lake: 6 miles long, a full day’s outing especially when you take into account the drive there and back, but one we shall certainly want to do on a future occasion. We will however have to take our own refreshments. The nearest café seems to be at Ennerdale Bridge, several miles away, and it had closed before we could get there. Perhaps it is a good thing that no-one has seen fit to construct a visitor centre or café at the lake, or even to park a refreshment van there. As I’m sure the partners are well aware, there is a fine balance to be struck between preservation and accessibility. Ennerdale’s principal attraction is not so much the scenery – the wide expanses of trees have a certain sameness to them – as its remoteness and tranquillity. The approach road is more difficult than, say, the corresponding approach to Wast Water which has a similarly remote location, and that probably plays its part in discouraging casual visitors. Still, I suspect it will not be long before the county council feels obliged to invest in further improvements.

It looks as if the partners have also upgraded the footpath round the lake: 6 miles long, a full day’s outing especially when you take into account the drive there and back, but one we shall certainly want to do on a future occasion. We will however have to take our own refreshments. The nearest café seems to be at Ennerdale Bridge, several miles away, and it had closed before we could get there. Perhaps it is a good thing that no-one has seen fit to construct a visitor centre or café at the lake, or even to park a refreshment van there. As I’m sure the partners are well aware, there is a fine balance to be struck between preservation and accessibility. Ennerdale’s principal attraction is not so much the scenery – the wide expanses of trees have a certain sameness to them – as its remoteness and tranquillity. The approach road is more difficult than, say, the corresponding approach to Wast Water which has a similarly remote location, and that probably plays its part in discouraging casual visitors. Still, I suspect it will not be long before the county council feels obliged to invest in further improvements.

Thanks to John as always for his photographs.

* Probably better known to you as the Forestry Commission and the Countryside Commission, respectively.

——————–

——————–

Ministry of Flat Walks 32 : Silverdale circuit

8 July 2021

To follow this walk, open another tab in your browser and input this web address: https://bit.ly/3hK0bxn.

The area round Arnside and Silverdale is one of our favourite places for walking. The area is criss-crossed by paths, most of which are not steep. This walk includes part of an earlier one (see 1 April 2018), but enough is different that it deserves separate inclusion in the Ministry.

Start at the car park shown in the top right hand corner of the map. You should be able to see the telephone symbol on the map: the car park entrance is just to the left, facing a minor road, The Row. The car park itself is little more than a rough clearing in the trees, packed earth with a little loose gravel. This, like much of the land round Silverdale, is National Trust land, and the Trust is responsible for the car park, but there is no charge.

From the car park, go north through a gate and along the track, up a very gentle slope until you meet the Eaves Wood path, marked as green dots on the map. Turn left here and follow the path steadily uphill through the wood. This is less taxing than I had feared (see the earlier blog). After a while another path leads to the left down a hill and then there is a fork in the route, with the right fork climbing further uphill. Take the left fork here and continue, with a high stone wall on your left and some curious low brick structures (possibly water tanks, now disused?) on your right, until you come to an opening with a tarmac road passing to your left and a bench to sit on.

From the car park, go north through a gate and along the track, up a very gentle slope until you meet the Eaves Wood path, marked as green dots on the map. Turn left here and follow the path steadily uphill through the wood. This is less taxing than I had feared (see the earlier blog). After a while another path leads to the left down a hill and then there is a fork in the route, with the right fork climbing further uphill. Take the left fork here and continue, with a high stone wall on your left and some curious low brick structures (possibly water tanks, now disused?) on your right, until you come to an opening with a tarmac road passing to your left and a bench to sit on.

Leave the path here, momentarily turning on to the tarmac and then back to your right (westwards) on a narrow gravelled path between walls.

Leave the path here, momentarily turning on to the tarmac and then back to your right (westwards) on a narrow gravelled path between walls.

Follow this path. It can be easy to miss your turning and end up in someone’s private drive, so take care. For a time the path joins a narrow road that provides access to some of the large houses in this corner of Silverdale. Keep going straight ahead, on the level – if you start climbing up or down a hill you have missed your way.

Eventually the access road takes a sharp turn to the left. Go straight ahead through another gap and very shortly you will find yourself alongside the Silverdale–Arnside road. Continue in the same direction, with an overgrown meadow behind metal railings on your left, to the corner where the road turns sharp right. Leave the main road here and walk down the lane towards The Cove, clearly signposted. This is evidently a well-known Silverdale location: we found Cove Road, Cove Lane, Cove Drive and Cove House.

Eventually the access road takes a sharp turn to the left. Go straight ahead through another gap and very shortly you will find yourself alongside the Silverdale–Arnside road. Continue in the same direction, with an overgrown meadow behind metal railings on your left, to the corner where the road turns sharp right. Leave the main road here and walk down the lane towards The Cove, clearly signposted. This is evidently a well-known Silverdale location: we found Cove Road, Cove Lane, Cove Drive and Cove House.

At the foot of the lane is the Cove itself, a corner of rough shingle sloping down to the mud of Morecambe Bay, or possibly to the sea if it is a high tide. On your right, accessible over rocks, is a small cave: John went to have a look, but from his account and his photos it is not really worth the effort.

At the foot of the lane is the Cove itself, a corner of rough shingle sloping down to the mud of Morecambe Bay, or possibly to the sea if it is a high tide. On your right, accessible over rocks, is a small cave: John went to have a look, but from his account and his photos it is not really worth the effort.

From the Cove a footpath, clearly visible and signposted, leads away southwards. For a hundred yards or so it clings to the cliff edge, and then turns inland through a stile on to an open meadow. The route across the meadow is well worn down and easy to follow.

The path crosses the meadow, through another stile and across another meadow, before emerging on to Lindeth Road at a sharp bend. (You can see the street names if you expand the map to its greatest magnification.) At this point you are back in Silverdale village. Turn left and follow the bend round to the right. Ignore the road that turns uphill to the left.

The path crosses the meadow, through another stile and across another meadow, before emerging on to Lindeth Road at a sharp bend. (You can see the street names if you expand the map to its greatest magnification.) At this point you are back in Silverdale village. Turn left and follow the bend round to the right. Ignore the road that turns uphill to the left.

Continue straight on and almost immediately there is a signpost pointing down a path to the right. Follow this path. This is not the most interesting part of the walk as you are passing the backs of gardens to right and left, and many of them are shielded by high walls or fences. However, after a while the left side of the path opens up at the edge of Scout Wood.

Continue straight on and almost immediately there is a signpost pointing down a path to the right. Follow this path. This is not the most interesting part of the walk as you are passing the backs of gardens to right and left, and many of them are shielded by high walls or fences. However, after a while the left side of the path opens up at the edge of Scout Wood.

Ignore all turnings to the right, and continue until you come to a T junction in the path. Turn left here and you will soon arrive at a tiny pond and a signpost. The pond is barely visible on the map: look just below and to the left of the blue W.

John and I made a mistake here. We wanted to follow the northbound route, which the signpost names as the cliff path. You can see the cliff on the map a good deal more easily than the pond. It’s not quite Beachy Head, but it is a vertical stone face, perhaps 25 feet higher on the eastern side, with trees to either side. Somehow John and I missed our way, and ended up on a false path through the bushes and trees on the lower side of the cliff. We became more and more tangled and eventually I stumbled, skinned my knee quite badly and bruised my leg in several places.

Eventually we fought our way up to the top and after a couple of dead ends found our way back to the path, but I strongly advise you to exercise more caution. Make sure that from the pond your route takes you up and above the cliff face. I’m not sure how we came to miss the path, but it must be there.

Eventually we fought our way up to the top and after a couple of dead ends found our way back to the path, but I strongly advise you to exercise more caution. Make sure that from the pond your route takes you up and above the cliff face. I’m not sure how we came to miss the path, but it must be there.

The correct path crosses an open patch of thick grass, then re-enters the wood. There is a sharp right turn and it runs behind some houses and through a narrow exit, with a tall hedge on the right and a driveway on the left, into Stankelt Road.

That’s the difficult bit done. Now turn right along the road for a couple of hundred yards, then turn left into Bottoms Lane. Walk along the lane for a couple of hundred yards until you come to a path leading off to the right, signposted to Burton Well and The Row. Take this path, which is very easy to follow, down a very gentle slope, around a bend to the left, until you come to the well. I’m afraid that, as a well, it’s a bit disappointing: it’s not round but rectangular, there is no bucket and chain but a stagnant pond half-covered with green slime.

The well stands at the entrance to Lambert’s Meadow, a rather damp patch of open grassland. indicated by a National Trust sign. Follow the path along the left hand side of the meadow until you come to a footbridge across the ditch – actually this “bridge” (see the symbol FB on the map) is no more than a low walkway. Cross the bridge to the far side of the meadow and continue through the woods down to The Row. Turn left, and follow the road back to the car park.

The well stands at the entrance to Lambert’s Meadow, a rather damp patch of open grassland. indicated by a National Trust sign. Follow the path along the left hand side of the meadow until you come to a footbridge across the ditch – actually this “bridge” (see the symbol FB on the map) is no more than a low walkway. Cross the bridge to the far side of the meadow and continue through the woods down to The Row. Turn left, and follow the road back to the car park.

Thanks to John for the photographs.

——————–

Ministry of Flat Walks 31 : Easedale

4 June 2021

To follow this walk, open another tab in your browser and input this web address: https://bit.ly/3cdqnhK.

I was in two minds about whether to publish a blog about this walk, which John and I undertook a few days ago. It was not one of our greatest successes. We were obliged to abandon part of the route I had planned, which turned out not to exist, and so were forced to retrace our steps, a there-and-back exercise which we usually prefer to avoid. However, after the first 100 yards or so the route is pretty flat, and offers an excellent view of the fells from a quiet valley within walking distance of one of Lakeland’s principal centres. So you may think it worthwhile. Some extra uphill exertion would take you to Easedale Tarn, high in the fells. That is too much for me these days, but you may have more endurance, or fortitude.

I was in two minds about whether to publish a blog about this walk, which John and I undertook a few days ago. It was not one of our greatest successes. We were obliged to abandon part of the route I had planned, which turned out not to exist, and so were forced to retrace our steps, a there-and-back exercise which we usually prefer to avoid. However, after the first 100 yards or so the route is pretty flat, and offers an excellent view of the fells from a quiet valley within walking distance of one of Lakeland’s principal centres. So you may think it worthwhile. Some extra uphill exertion would take you to Easedale Tarn, high in the fells. That is too much for me these days, but you may have more endurance, or fortitude.

The walk starts at the crossroads in the centre of Grasmere, where the main road (a loop off the A590 Ambleside to Keswick trunk route) makes a right-angle bend. You can see the spot in the bottom right hand corner of the map; a telephone box symbol points it out. However, you may have to walk a fair way even to get this far. Grasmere has two public car parks but on busy days they can both fill up, and you will then be reduced to searching for kerbside or off-road parking further away from the centre. Don’t say you weren’t warned.

From the crossroads head north west along the route marked with green circles on the map. After a few yards the road starts to climb and passes a notice stating that it leads up to the National Trust property at Allan Bank. (John tells me that he has been here once before, as Allan Bank is one of the sites where red squirrels may be seen, though he didn’t spot any.) However, you need not climb very far. Soon a gravelled footpath leads away to the right and winds its way across a grassy meadow. Follow this path until you come to Easedale Road, which is named on the map. The path now runs parallel to the road, but separated from it by a tall hedge, until you come to Goody Bridge.

From the crossroads head north west along the route marked with green circles on the map. After a few yards the road starts to climb and passes a notice stating that it leads up to the National Trust property at Allan Bank. (John tells me that he has been here once before, as Allan Bank is one of the sites where red squirrels may be seen, though he didn’t spot any.) However, you need not climb very far. Soon a gravelled footpath leads away to the right and winds its way across a grassy meadow. Follow this path until you come to Easedale Road, which is named on the map. The path now runs parallel to the road, but separated from it by a tall hedge, until you come to Goody Bridge.

You are now in a part of Grasmere well away from the usual tourist spots and it is fairly quiet, though you will certainly encounter other walkers. Follow Easedale Road over the bridge and continue straight ahead until the road bends to the right. Shortly afterwards, this road will turn westwards and follow the north side of Easedale towards Lancrigg, from where a path continues further up the valley and into the fells. We had hoped to be able to return along this path. However, where the road first bends to the right there is also a path leading straight on across a bridge over Easedale Beck. (The map marks a ford here, but there is no need to get your feet wet.) Follow this path, which continues its more or less straight course up the south side of the valley, with the fells ahead and on both sides.

After a few hundred yards you will come to New Bridge, which stands almost isolated in the middle of the fields. A barely visible track from here crosses the beck and leads towards a group of buildings at Lancrigg. You could make a short loop by following this track and returning along the road. We, however, were hoping to make a longer loop further towards the head of the valley, and continued along the main path.

After a few hundred yards you will come to New Bridge, which stands almost isolated in the middle of the fields. A barely visible track from here crosses the beck and leads towards a group of buildings at Lancrigg. You could make a short loop by following this track and returning along the road. We, however, were hoping to make a longer loop further towards the head of the valley, and continued along the main path.

Another few hundred yards further on you will come to a gate where the path crosses a farm track that leads on the right to Brimmer Head Farm. We met a postman here and asked us whether it was possible to cross to the other side of the valley from further along, but he didn’t know. He did tell us that, though he had himself driven through Brimmer Head Farm, that was by permission; the track is gated and marked Private. The “right to roam” extends across much of the Lake District, but it does not include farmyards, and in any event I would not want to walk across someone’s yard without permission. So this route across the valley is blocked.

Just the same, it’s a shame that Brimmer Head Farm is kept private. According to Historic England, parts of the building date back to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It would be interesting to have a closer look.

After crossing the farm track the path continues onward, climbing gently at first and then more steeply. You can see this very clearly in the top left corner of the map where the contour lines start to gather. From here the path climbs, quite steeply and very steadily, up the mountainside until it disappears over the crest to Easedale Tarn, not shown on the map. If you are feeling energetic you might want to make the attempt; according to signposts the distance is less than a mile. We did not.

I had hoped that we might be able to make our way from here across to the other side of the valley, thus enabling us to complete a loop. If you look carefully at the map you can see there are two walls close together, suggestive of a path. However, if you look even more closely you will see that the black dots which show the line of a minor path lead across the first stream and then swing uphill, parallel to a wall, around Ecton Crag. Alas, there are no gates or stiles in this wall, and no other way across that we could find. So we were forced to turn back, disappointed.

Back in Grasmere we took solace in a cup of tea in one of the many cafés and then paid a visit to Barney’s, a newsagent and gift shop which offers a fine selection of jigsaws. Who would expect to find this in Grasmere? I bought several which John kindly carried for me back to the car.

I am not sorry to have visited Easedale, one of the corners of the Lake District we had not previously explored. The walk up and back is a nice stroll, quiet and free of traffic. But I confess that I did not find it altogether satisfying.

Many thanks to John for the use of his photographs.

——————–

Ministry of Flat Walks 30 : Nether Wasdale

3 June 2021

To follow this walk, open another tab in your browser and input this web address: https://bit.ly/3ph0Ucz. I have used the 1:50,000 scale map here so as to show the entire route, but you may also find it helpful to use 1:25,000 scale, as it includes extra detail such as field boundaries. To do so, use the zoom control in the bottom right hand corner of the screen.

To follow this walk, open another tab in your browser and input this web address: https://bit.ly/3ph0Ucz. I have used the 1:50,000 scale map here so as to show the entire route, but you may also find it helpful to use 1:25,000 scale, as it includes extra detail such as field boundaries. To do so, use the zoom control in the bottom right hand corner of the screen.

This is a walk of 5 to 6 miles, with only a few very minor climbs. Wastwater is one of our favourite places in the Lakes, but does not offer many options for flat walking, so we are very pleased to have found this one. It makes use of a number of well-laid paths which I imagine did not exist when our family were regular visitors to the area in the years before 2001.

The walk starts in the bottom left hand corner of the map at the little triangle of roads just east of Nether Wasdale village. You should be able to park your car here on one of the verges, though in some places they have been blocked off with stones. Be very cautious about using the signed parking area: it contains spaces for only a handful of cars, and backing out again is tricky, as we found out the hard way.

Head south across the bridge and immediately turn left on to the farm track towards Easthwaite. The track is wide enough for a tractor and well surfaced with sandy gravel. You will have an excellent view from here up the valley to the lake and the fells beyond. Continue on the track, which now bends to the left round the farm buildings at Easthwaite – the 1:50,000 map is not quite up to date on this point. Continue through a gate to a junction and bear left, now heading north east directly towards the foot of the lake. This is the same track that you would follow if you were planning to walk across the screes on the south east side of the lake, a course I do not recommend as it is hard work and unrewarding.

Head south across the bridge and immediately turn left on to the farm track towards Easthwaite. The track is wide enough for a tractor and well surfaced with sandy gravel. You will have an excellent view from here up the valley to the lake and the fells beyond. Continue on the track, which now bends to the left round the farm buildings at Easthwaite – the 1:50,000 map is not quite up to date on this point. Continue through a gate to a junction and bear left, now heading north east directly towards the foot of the lake. This is the same track that you would follow if you were planning to walk across the screes on the south east side of the lake, a course I do not recommend as it is hard work and unrewarding.

After a while the track turns eastwards and passes through another gate into a grassy meadow. Turn left here, leaving the route towards the screes, and walk across the grass, following the hedge now on your left down to the river at Lund Bridge. There is a wire fence at the foot of the meadow but a wooden gate allows access on to the riverside path. Turn left on to this path and cross the bridge.

After a while the track turns eastwards and passes through another gate into a grassy meadow. Turn left here, leaving the route towards the screes, and walk across the grass, following the hedge now on your left down to the river at Lund Bridge. There is a wire fence at the foot of the meadow but a wooden gate allows access on to the riverside path. Turn left on to this path and cross the bridge.

Ahead is a farm track barred by a gate. Beyond this gate, barely visible in the photograph below, is another small gate in the stone wall on your right.

Go through this small gate and turn right on to the path that makes its way round the edge of Low Wood. I am told that the wood is carpeted in bluebells in April and early May, but this year we were just too late. The path starts through the wood but quickly drops down towards the water’s edge.

Go through this small gate and turn right on to the path that makes its way round the edge of Low Wood. I am told that the wood is carpeted in bluebells in April and early May, but this year we were just too late. The path starts through the wood but quickly drops down towards the water’s edge.

Before you reach Wastwater proper there is a small lagoon here, attractive and very still even on a windy day. This lagoon offers picnic places on both banks, very attractive for families with children, especially on the far bank which is grassy and open. The only way to cross the water is by swimming (or by boat, I suppose) but you can reach the far bank quite simply by continuing along the path towards the screes, mentioned earlier. Along the Low Wood path there are several benches where you, like we, can sit and eat your picnic while admiring the view up the lake.

Before you reach Wastwater proper there is a small lagoon here, attractive and very still even on a windy day. This lagoon offers picnic places on both banks, very attractive for families with children, especially on the far bank which is grassy and open. The only way to cross the water is by swimming (or by boat, I suppose) but you can reach the far bank quite simply by continuing along the path towards the screes, mentioned earlier. Along the Low Wood path there are several benches where you, like we, can sit and eat your picnic while admiring the view up the lake.

The path winds its way along the side of the lake, gradually turning left around the headland. Now the woods gradually give way to meadow, and the path turns back to the right (that is, north east), passing Wasdale Hall on your left. The Hall is now a youth hostel, but this is not hostelling as our Mum would have known it: we found several cars parked outside, along with a trailer loaded with canoes. Clearly this is a well-known launching place, though the wind blowing down the lake from the hills must sometimes make things tricky for canoeists.

The path winds its way along the side of the lake, gradually turning left around the headland. Now the woods gradually give way to meadow, and the path turns back to the right (that is, north east), passing Wasdale Hall on your left. The Hall is now a youth hostel, but this is not hostelling as our Mum would have known it: we found several cars parked outside, along with a trailer loaded with canoes. Clearly this is a well-known launching place, though the wind blowing down the lake from the hills must sometimes make things tricky for canoeists.

The path now passes through a small clump of rhododendrons and you come to a set of steps hewn into the rock leading up to a gap in a stone wall. There are only about eight steps up in total – not too difficult, though my sudden appearance in the gap did startle a woman on the other side who wasn’t looking. Beyond the wall is the road which runs alongside the lake up to Wasdale Head. This is a minor road, single track with passing places, but at holiday time it can be busy, so take care. Over the last few years drivers have started parking their cars on the carriageway itself, as well as in the various off-road spaces, which adds to congestion and probably a few lost tempers as well. I imagine yellow no-parking lines are not far off in the future.

The path now passes through a small clump of rhododendrons and you come to a set of steps hewn into the rock leading up to a gap in a stone wall. There are only about eight steps up in total – not too difficult, though my sudden appearance in the gap did startle a woman on the other side who wasn’t looking. Beyond the wall is the road which runs alongside the lake up to Wasdale Head. This is a minor road, single track with passing places, but at holiday time it can be busy, so take care. Over the last few years drivers have started parking their cars on the carriageway itself, as well as in the various off-road spaces, which adds to congestion and probably a few lost tempers as well. I imagine yellow no-parking lines are not far off in the future.

Follow this road along the side of the lake and over the stone bridge across the beck (which I see from the map is called Countess Beck, though I have never heard that name anywhere else). At the next junction turn left. You can try a short cut here if you prefer – the map suggests one possibility. But the ground can be marshy and the beck, which runs through a surprisingly deep gully, can be awkward to cross.

From here the road runs across the heathland for several hundred yards broadly westwards before reaching a clump of buildings at Greendale and crossing a bridge (easily missed) over Greendale Gill. Just beyond the bridge a signpost points down a footpath to the left. Turn on to this path, which follows the line of the gill southwards through Roan Wood. This is a very attractive part of the walk through a very different type of woodland from Low Wood – there is much more greenery and undergrowth here, but the path is clear to follow, though we did have to clamber over a couple of fallen trees.

From here the road runs across the heathland for several hundred yards broadly westwards before reaching a clump of buildings at Greendale and crossing a bridge (easily missed) over Greendale Gill. Just beyond the bridge a signpost points down a footpath to the left. Turn on to this path, which follows the line of the gill southwards through Roan Wood. This is a very attractive part of the walk through a very different type of woodland from Low Wood – there is much more greenery and undergrowth here, but the path is clear to follow, though we did have to clamber over a couple of fallen trees.

This path eventually comes to a stone wall and turns right, leading up to a field gate. Go through this gate into open hill pasture. You may find the 1:25,000 map particularly useful here, using the field boundaries to help navigate where the line of the path is unclear. The ground has clumps of reeds and is marshy in places which you may need to find your way around, but so long as you continue to head broadly south west you should be fine. Dabs of yellow paint on rocks show the way – you can just see one in the picture below.

After crossing the first field into open heath the track becomes clearer. The western corner of this patch of land is named on the map as Ashness How, and from here you are back on farm tracks. Continue straight on until the track takes a sharp turn to the left and leads down to the road. Turn right here, and within a couple of hundred yards you are back at your starting point.

After crossing the first field into open heath the track becomes clearer. The western corner of this patch of land is named on the map as Ashness How, and from here you are back on farm tracks. Continue straight on until the track takes a sharp turn to the left and leads down to the road. Turn right here, and within a couple of hundred yards you are back at your starting point.

Although Roan Wood was a pleasant walk, the final stage of this route, wet in places and without a clear path, was a bit annoying. We will probably do this walk again, and I think we may try an alternative to this final stage, continuing on the road a little further to Buckbarrow and then turning on to the marked path past Scale Bridge and Mill Place.

Thanks as always to John for his excellent photos.

——————–

Ministry of Flat Walks 29 : Malham

3 June 2021

This blog was written in early May but not posted immediately as I had some problems with the website’s Edit functions. I hope all is now OK.

This blog was written in early May but not posted immediately as I had some problems with the website’s Edit functions. I hope all is now OK.

To follow this walk, open another tab in your browser and input this web address: https://bit.ly/3uqFYlm. There are two short walks here, each starting and finishing in Malham village, but they are short enough to be combined in a single visit, as John and I did this week. The same map will do for both.

I first visited Malham on a school trip in 1967. I remember the year, because that spring I had surgery for appendicitis and was forbidden any strenuous exercise for fear of tearing open the wound. I resented not being able to play cricket that year; and, though I was able to join the party for Malham, I had to stay in the village while the other boys walked and climbed to see all the interesting geology which was the ostensible reason for the trip.

In the decades since then, Malham has become a well-known destination for day trips. On the south west edge of the Yorkshire Dales, half way between Skipton and Settle, it is well within reach from Bradford and Leeds, and not much further from Liverpool and Manchester. As a result it becomes very crowded in high summer and during school holidays. I strongly recommend, if you wish to visit or to follow these walks, that you do so on a sunny midweek day in spring or early summer before the schools break up for their holidays. There will still be plenty of people around, but you will not feel crowded out.

Malham is approached by road from the south, and at the entrance to the village is a large car park run by the National Park authority. The fee for day-long parking is modest. There is no parking in the village itself, but the car park is a bare 200 yards short of the low stone bridge across Malham Beck which is at the centre of the village. Just beyond the bridge is the village green, and clustered around on both sides of the beck, are several pubs and cafés. On a previous visit John and I had a memorable cream tea in one of these establishments.

For the first walk, start from the car park and walk into the village but do not cross the bridge. Continue on the road northwards. When you come to a sign warning that the road ahead is steep, on the right you will see a gate in the stone wall. Go through this gate and follow the gravel path which leads steadily towards the sheer limestone face that is Malham’s chief attraction. You absolutely cannot miss it. The fields at this time of year are full of sheep and lambs, so if you have a dog it must be kept on a lead (and is probably better left at home). We encountered a couple of dogs which, despite all the warning signs, had been let off the leash. There are some irresponsible people around.

For the first walk, start from the car park and walk into the village but do not cross the bridge. Continue on the road northwards. When you come to a sign warning that the road ahead is steep, on the right you will see a gate in the stone wall. Go through this gate and follow the gravel path which leads steadily towards the sheer limestone face that is Malham’s chief attraction. You absolutely cannot miss it. The fields at this time of year are full of sheep and lambs, so if you have a dog it must be kept on a lead (and is probably better left at home). We encountered a couple of dogs which, despite all the warning signs, had been let off the leash. There are some irresponsible people around.

The area at the foot of the cliff is known as Malham Cove. You can only get right up to the cliff face if you are prepared to get your feet wet, or have brought your wellington boots. But you can get quite close enough to be awestruck by the vertical cliff face, more than 250 feet high. You may occasionally see climbers attempting the ascent; several routes are known. On your left is a path – really more of a scramble – up to the top of the cliff, as mentioned below. At the foot of the cliff is a cave from which the stream emerges, but it is for serious cavers only.

The area at the foot of the cliff is known as Malham Cove. You can only get right up to the cliff face if you are prepared to get your feet wet, or have brought your wellington boots. But you can get quite close enough to be awestruck by the vertical cliff face, more than 250 feet high. You may occasionally see climbers attempting the ascent; several routes are known. On your left is a path – really more of a scramble – up to the top of the cliff, as mentioned below. At the foot of the cliff is a cave from which the stream emerges, but it is for serious cavers only.

Turning back towards Malham, you will soon see on your left a low bridge – really, no more than stone slabs – across the beck. Walk over this bridge, marked FB on the map, and up the grassy bank. There is no marked path here but the route is fairly obvious. The climb is short and only moderately steep. Perhaps 30 feet up you will come to a path, not gravel but clear to follow, leading across the hillside. Simply follow this path back into Malham.

Turning back towards Malham, you will soon see on your left a low bridge – really, no more than stone slabs – across the beck. Walk over this bridge, marked FB on the map, and up the grassy bank. There is no marked path here but the route is fairly obvious. The climb is short and only moderately steep. Perhaps 30 feet up you will come to a path, not gravel but clear to follow, leading across the hillside. Simply follow this path back into Malham.

As you reach the village you will cross this picturesque slate bridge.

As you reach the village you will cross this picturesque slate bridge.

The total length of this walk is no more than two miles and it is easily done in an hour plus time for admiring the scenery and taking photographs

Starting the second walk also from the car park, head towards the village centre with the beck on your right, but before you come to the main bridge cross a smaller pedestrian only bridge and turn back southwards along the path on the east side of the beck.

Go through a gate and follow the path, which is well gravelled, as it turns to the left across grassy meadows.

Go through a gate and follow the path, which is well gravelled, as it turns to the left across grassy meadows.

After half a mile or so the path heads into a wooded dell filled with wild garlic plants – their scent is quite noticeable. Slowly the path climbs and its surface becomes less even until you come to a large pool in the beck fed by a sheer waterfall. This is Janet’s Foss – you can see the name on the map. You may well find there are people splashing and swimming in the pool, though the water must be icy cold, especially at this time of year.

After half a mile or so the path heads into a wooded dell filled with wild garlic plants – their scent is quite noticeable. Slowly the path climbs and its surface becomes less even until you come to a large pool in the beck fed by a sheer waterfall. This is Janet’s Foss – you can see the name on the map. You may well find there are people splashing and swimming in the pool, though the water must be icy cold, especially at this time of year.

This is the top of the dell and the path ends here, but to the left of the falls you can clamber up over the rocks, no more than 30 feet or so, on to the road above. This is a bit of a scramble and you may need hands as well as feet, but it is a very short section and not too difficult. When you reach the top the landscape has changed completely and you are suddenly in semi-wild moorland – fields demarcated by dry stone walls, frequent patches of bald rock peering out through bare grass.

This is the top of the dell and the path ends here, but to the left of the falls you can clamber up over the rocks, no more than 30 feet or so, on to the road above. This is a bit of a scramble and you may need hands as well as feet, but it is a very short section and not too difficult. When you reach the top the landscape has changed completely and you are suddenly in semi-wild moorland – fields demarcated by dry stone walls, frequent patches of bald rock peering out through bare grass.

The road here, Gordale Lane, is a cul-de-sac. To your right it leads up only to farmhouses, so you will encounter very little traffic: probably more walkers than vehicles. Turn left on to the road. There is a further climb for a couple of hundred yards and then you start to descend slowly back into Malham village. The walk when completed is about two miles long.

The road here, Gordale Lane, is a cul-de-sac. To your right it leads up only to farmhouses, so you will encounter very little traffic: probably more walkers than vehicles. Turn left on to the road. There is a further climb for a couple of hundred yards and then you start to descend slowly back into Malham village. The walk when completed is about two miles long.

A much longer walk is possible, continuing from Gordale Lane, but it is a good deal more challenging and I have not attempted it for some years. Starting from Gordale Bridge, this path – named on the map as the Dales High Way – climbs across the fields, crosses another road and turns westwards to the top of the cliff at Malham Cove. If you can manage the extra effort it’s worth doing this, as you can admire the limestone formations, and enjoy a magnificent view southwards towards Malham village and beyond. From here there is a well-trodden scramble down to the valley floor, as mentioned earlier. Lots of people do go this way, but it cannot by the widest stretch of the imagination be called a flat walk.

Many thanks to John, as always, for the use of his photographs.

——————–

Ministry of Flat Walks 28 : Smardale

21 August 2020

To follow this walk, open another tab in your browser and input this web address: https://bit.ly/3j0TSo3. Be warned, however, that very unusually this map is not quite up to date and does not include some useful details.

Please also be warned that to complete this walk as described involves an act of trespass. When we were there, no-one else seemed to be paying much attention to the No Entry signs; but still, if you are particularly law-abiding, you should look away now.

This was our first new walk for some time. I had not been up in Cark since the start of the Covid pandemic in the UK until I drove up for a fortnight’s holiday a few days ago. John has been here almost every weekend since the first easing of lockdown, so the house has at least been lived in. But I dare not commit myself to a train journey, and the six-hour drive up from Oxted is far too much for a casual weekend.

The idea of a walk in Smardale was not new. I had spotted the possibilities when looking at the Ordnance map of the area some months ago. And the walk features in a guidebook of local nature reserves which we were given when we joined Cumbrian Wildlife. John has evidently been making excellent use of the guidebook while I have been absent.

This is quite a long walk – about six miles – and involves some backtracking at start and finish, which I usually prefer to avoid, but in this case it is worthwhile. Two thirds of the distance is along an old railway line converted to a path, which is flat and easy walking. The loop at the far end dips down to the valley floor and the climb back up is quite strenuous and rough in places but not really steep.

Smardale Gill is a steep sided valley in the fells west of Kirkby Stephen. Scandal Beck (sic) runs along the valley floor. At one time the valley was threaded by a railway which ran from Tebay to Kirkby Stephen and on to Barnard Castle, built primarily as a freight route for coal trains from Northumberland to Barrow. The Smardale section of the line was closed in 1952, but the trackbed which runs along the side of the valley remains, as does Smardale Gill viaduct, a remarkable curving structure with 14 arches half way down the valley. The central section of the valley, including the trackbed, is now a protected nature reserve and Site of Special Scientific Interest. The viaduct is a preserved structure, maintained by the Northern Viaduct Trust.

There are (I understand) car parking opportunities at Brownber, near the south end of the dale, but we preferred to start at the north end where there is a small car park maintained by Cumbrian Wildlife. It’s not shown on the map, but if you follow the road in the top right corner eastwards from the ford, past the drive to Smardale Hall and another road leading off to the right, the car park is about 200 yards further along on the right, occupying a section of the old railway.

From the car park you walk west, up a boardwalk which leads back up to the road just before the junction, and straight on to the Smardale Hall drive. On your left here are the remains of Smardale station, which looks over-provided for the tiny community it served. The station building has been converted very elegantly into a private home and you can still see the remains of the two platforms in John’s photograph. As usual, my thanks to him for all the photos I have used to illustrate this blog.

From the car park you walk west, up a boardwalk which leads back up to the road just before the junction, and straight on to the Smardale Hall drive. On your left here are the remains of Smardale station, which looks over-provided for the tiny community it served. The station building has been converted very elegantly into a private home and you can still see the remains of the two platforms in John’s photograph. As usual, my thanks to him for all the photos I have used to illustrate this blog.

Turn left on to the Hall drive and immediately right through a gate up to the old railway. Now you can follow the trackbed all the way to Smardale Gill viaduct. A short way along you will pass under an arch of another viaduct, Smardale Viaduct, on the still-operational Settle to Carlisle line. Nearby is a rusting metal framework of another bridge over the path, but we were unable to determine its history and purpose; it is not mentioned in any of the guides we have consulted.

Turn left on to the Hall drive and immediately right through a gate up to the old railway. Now you can follow the trackbed all the way to Smardale Gill viaduct. A short way along you will pass under an arch of another viaduct, Smardale Viaduct, on the still-operational Settle to Carlisle line. Nearby is a rusting metal framework of another bridge over the path, but we were unable to determine its history and purpose; it is not mentioned in any of the guides we have consulted.

The next stretch of the walk is very pleasant, as flat as you could possibly wish, mostly through woodland with occasional breaks in the trees through which you can see the other side of the valley. John really enjoyed himself photographing butterflies, and we spotted at least six different varieties: Red Admirals, Peacocks, Meadow Browns, Dark Green Fritillaries (confusingly, not green at all, but orange with dark spots), some unidentified white butterflies and the rare Scotch Argus. We had our picnic lunch on one of the benches along this section: there are several.

The next stretch of the walk is very pleasant, as flat as you could possibly wish, mostly through woodland with occasional breaks in the trees through which you can see the other side of the valley. John really enjoyed himself photographing butterflies, and we spotted at least six different varieties: Red Admirals, Peacocks, Meadow Browns, Dark Green Fritillaries (confusingly, not green at all, but orange with dark spots), some unidentified white butterflies and the rare Scotch Argus. We had our picnic lunch on one of the benches along this section: there are several.

The route of the published walk extends over Smardale Gill viaduct, but it appears that health and safety panjandrums have determined that the railings on either side of the viaduct (which is wide enough to accommodate a double track railway – at least 15 ft wide) are unsafe, and it has been closed to pedestrians. However, the closure appears to be rather half-hearted. The fences that have been erected at each end are easily bypassed, and several groups of walkers seemed happy to do so. I would be uneasy allowing a young child to walk across unsupervised, but complete closure does seem unnecessarily officious. It is clearly also unenforced, and largely ignored.

The route of the published walk extends over Smardale Gill viaduct, but it appears that health and safety panjandrums have determined that the railings on either side of the viaduct (which is wide enough to accommodate a double track railway – at least 15 ft wide) are unsafe, and it has been closed to pedestrians. However, the closure appears to be rather half-hearted. The fences that have been erected at each end are easily bypassed, and several groups of walkers seemed happy to do so. I would be uneasy allowing a young child to walk across unsupervised, but complete closure does seem unnecessarily officious. It is clearly also unenforced, and largely ignored.

Anyway. From the other side of the viaduct, the line of the railway continues down the other side of the valley, now on a ledge across typical fell country. A short way along on the right are the arches of two old lime kilns, and as the line starts to turn away to the right (westwards) you come to a short cutting and an overbridge. On the far side of this bridge, to the left, are steps leading up the side of the cutting. Turn up these steps which join a well marked footpath that leads down to the floor of the valley. This path is marked on the map with short red dashes, and crosses a tributary beck on stepping stones (on the map this is at the marked 221 ft spot height) to join a track leading west and east. The track west leads down towards Brownber. Instead, turn left (eastwards) here and cross Smardale Bridge.

Anyway. From the other side of the viaduct, the line of the railway continues down the other side of the valley, now on a ledge across typical fell country. A short way along on the right are the arches of two old lime kilns, and as the line starts to turn away to the right (westwards) you come to a short cutting and an overbridge. On the far side of this bridge, to the left, are steps leading up the side of the cutting. Turn up these steps which join a well marked footpath that leads down to the floor of the valley. This path is marked on the map with short red dashes, and crosses a tributary beck on stepping stones (on the map this is at the marked 221 ft spot height) to join a track leading west and east. The track west leads down towards Brownber. Instead, turn left (eastwards) here and cross Smardale Bridge.

This is the toughest section of the walk as you now need to follow the track uphill for a couple of hundred yards until you come to a gap in the wall to your left with an signpost. Go through the gap and join the path signed back to Smardale. This path is not marked on the map at all, but it more or less follows the line of the beck northwards, rejoining the old railway just east of the viaduct. The path is uneven, somewhat up and down but rising towards the end, and is muddy in places, but it offers excellent views in both directions.

This is the toughest section of the walk as you now need to follow the track uphill for a couple of hundred yards until you come to a gap in the wall to your left with an signpost. Go through the gap and join the path signed back to Smardale. This path is not marked on the map at all, but it more or less follows the line of the beck northwards, rejoining the old railway just east of the viaduct. The path is uneven, somewhat up and down but rising towards the end, and is muddy in places, but it offers excellent views in both directions.

One feature which John and I both found fascinating is that, while the crags on the west side of the valley are clearly limestone, as is confirmed by the presence of old lime kilns, equally clearly the rock on the east side is red sandstone. It was unclear to us whether this just happens to be a geological fault line or boundary, or whether one or other stone is an outcrop. John’s photograph shows the contrast very clearly. I have not been able to find a sufficiently detailed geological map which might answer the question.

From the viaduct you simply retrace your steps back to the car park.

——————–

Vallotton

25 October 2019

A few weeks ago John and I went to the Royal Academy to see an exhibition of work (paintings and prints) by the Swiss-French artist Félix Vallotton. I have become increasingly choosy about the exhibitions I visit: so John was, I think, a little puzzled what it was that had attracted my interest.

A few weeks ago John and I went to the Royal Academy to see an exhibition of work (paintings and prints) by the Swiss-French artist Félix Vallotton. I have become increasingly choosy about the exhibitions I visit: so John was, I think, a little puzzled what it was that had attracted my interest.

I did at least know Vallotton’s name, which is not always the case with the exhibitions John goes to see. More specifically, Vallotton was a contemporary and colleague of Pierre Bonnard, about whose work I wrote in a previous blog (15 March 2019), and of Édouard Vuillard among others.

The RA exhibition was subtitled Painter of Disquiet. I’m not entirely sure about that, but it is true that quite a lot of the paintings on display have an ambiguous quality. Here are a couple of examples. The first is from 1892, early in his career, titled La Malade (The Patient). At first it looks well executed but unexceptional. Look again. The maid seems scarcely aware of the patient. The relationship between the two figures is distinctly odd, and strongly contrasting. What exactly is going on here?

The RA exhibition was subtitled Painter of Disquiet. I’m not entirely sure about that, but it is true that quite a lot of the paintings on display have an ambiguous quality. Here are a couple of examples. The first is from 1892, early in his career, titled La Malade (The Patient). At first it looks well executed but unexceptional. Look again. The maid seems scarcely aware of the patient. The relationship between the two figures is distinctly odd, and strongly contrasting. What exactly is going on here?

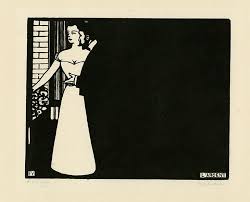

Here’s another painting, from 1903: Interior with Woman in Red. Is that a mirror ahead of us, mounted on the door of a wardrobe? And if so why doesn’t it reflect the room in front of it? Or is it another doorway, leading to another room, leading to another doorway? I am not over-fond of the idea that paintings contain narrative: at best they illustrate scenes from a longer narrative. In classical paintings from mythology we know what the narrative is, but in these paintings by Vallotton we have to make it up for ourselves, and there aren’t many clues to guide us.

Here’s another painting, from 1903: Interior with Woman in Red. Is that a mirror ahead of us, mounted on the door of a wardrobe? And if so why doesn’t it reflect the room in front of it? Or is it another doorway, leading to another room, leading to another doorway? I am not over-fond of the idea that paintings contain narrative: at best they illustrate scenes from a longer narrative. In classical paintings from mythology we know what the narrative is, but in these paintings by Vallotton we have to make it up for ourselves, and there aren’t many clues to guide us.

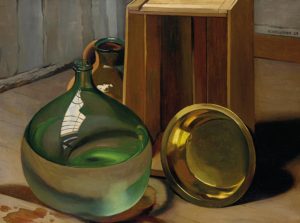

Vallotton was an artist with a very wide range of subjects: not just these ambiguous scenes, but landscapes (urban and rural), still lifes, portraits and nudes. The exhibition included examples of all these genres. Disquiet is present, I should say, in only a small number of them. But perhaps detachment would be nearer the mark. Still lifes, of course, are the perfect opportunity for detachment, for the artist to display his or her skill without any overlaid emotional content. I particularly admired this late painting, Demi-Jeanne et Caisse (1925), for its use of light and reflection. This may be a modern(ish) painting but it is absolutely classical in its subject and approach.

Vallotton was an artist with a very wide range of subjects: not just these ambiguous scenes, but landscapes (urban and rural), still lifes, portraits and nudes. The exhibition included examples of all these genres. Disquiet is present, I should say, in only a small number of them. But perhaps detachment would be nearer the mark. Still lifes, of course, are the perfect opportunity for detachment, for the artist to display his or her skill without any overlaid emotional content. I particularly admired this late painting, Demi-Jeanne et Caisse (1925), for its use of light and reflection. This may be a modern(ish) painting but it is absolutely classical in its subject and approach.

The portraits frankly didn’t mean much to me, but I was very struck by this self-portrait, made when Vallotton was a young man. It’s too easy to find in a picture what we want or expect to find, but this painting does seem to me to capture the notion of Vallotton the detached observer.

The portraits frankly didn’t mean much to me, but I was very struck by this self-portrait, made when Vallotton was a young man. It’s too easy to find in a picture what we want or expect to find, but this painting does seem to me to capture the notion of Vallotton the detached observer.

As for the nudes, the exhibition had several, of which the most striking is probably La Blanche et La Noire. Is it just me, or does the white girl’s posture look positively uncomfortable? And what’s happened to her left arm? This is another painting which, if it doesn’t precisely tell a story, seems to demand one which we are left to fill in for ourselves; Vallotton leaves no clues.

For me, though, Vallotton’s most interesting and attractive paintings are the landscapes. Sometimes these, too, are ambiguous, or invite us to imagine a story. The Ball at first looks like a landscape, not a very interesting one either. But where exactly is the ball?

For me, though, Vallotton’s most interesting and attractive paintings are the landscapes. Sometimes these, too, are ambiguous, or invite us to imagine a story. The Ball at first looks like a landscape, not a very interesting one either. But where exactly is the ball?

You don’t see it at first: it’s a little red dot, barely distinguishable, in bottom right. And what’s going on in the background? Is there any relationship between the young figure with the ball and the distant couple?

You don’t see it at first: it’s a little red dot, barely distinguishable, in bottom right. And what’s going on in the background? Is there any relationship between the young figure with the ball and the distant couple?

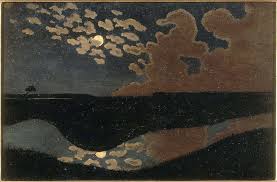

Not all of his landscapes contain these ambiguities. Here are two more, both on view at the exhibition, but painted almost thirty years apart: Moonlight (from 1895) and Sandbanks on the Loire (1923).

In Moonlight you can see how Vallotton came to be thought of as post-impressionist, although to my eye there’s also an expressionist quality to this painting, conveying feeling as much as image. It is at any rate not at all naturalistic. Sandbanks on the Loire, however, is very characteristic of a lot of Vallotton’s later work, much more true to life, though in a highly stylised, simplified form.

In Moonlight you can see how Vallotton came to be thought of as post-impressionist, although to my eye there’s also an expressionist quality to this painting, conveying feeling as much as image. It is at any rate not at all naturalistic. Sandbanks on the Loire, however, is very characteristic of a lot of Vallotton’s later work, much more true to life, though in a highly stylised, simplified form.