Salomé

30 July 2017

John and I generally reckon to visit Stratford-on-Avon four or five times a year, to see productions in one of the Royal Shakespeare Company’s two theatres. As a general rule, the main theatre is used for Shakespeare productions, which are more popular, not least with the American and other tourists who populate Stratford in great numbers, especially during the summer. The smaller theatre, the Swan, is used for a wider variety of plays, but with an emphasis on the work of Shakespeare’s contemporaries, and on new plays.

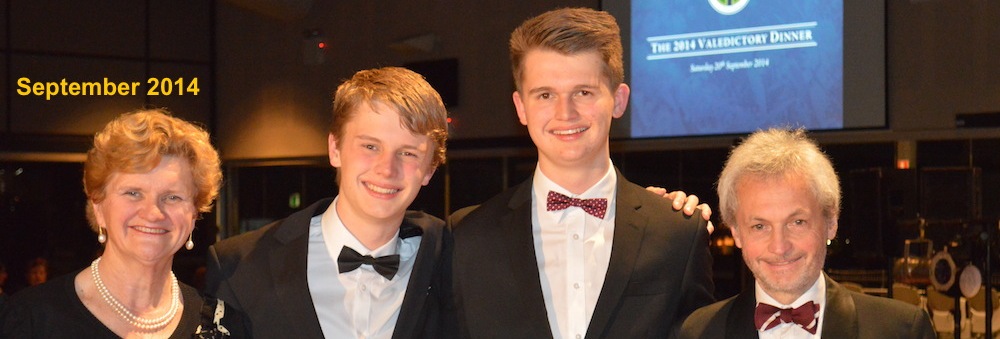

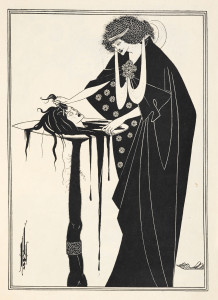

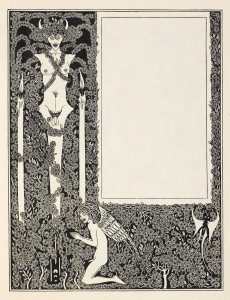

We have become quite picky about what Shakespeare we choose to see. Some plays are done too often, or we have seen such good productions already that we are in no hurry to see them again. But we may be attracted by a favourite play (Much Ado), or a good director (Gregory Doran), or a rarity we haven’t seen recently (Troilus and Cressida). We generally prefer the Swan, especially its revivals of older plays. This year, however, the Swan has moved away from its usual repertoire. We have already seen Vice Versa, a new play by Phil Porter based on an old Roman comedy by Plautus, which we enjoyed, though I didn’t blog afterwards as I didn’t have much to say about it. And this weekend we have been to see a rare production of Oscar Wilde’s Salomé.

The play was originally written in French, at a time when Wilde was living in Paris and influenced by the literary and artistic movements there. But within a couple of years it had been translated into English. The show consists of a single act lasting about ninety minutes, and has a classical unity of time and place. Its story is the infatuation of Salomé, King Herod’s daughter, with the imprisoned Jokanaan (John the Baptist). When he rejects her, she performs the notorious Dance of the Seven Veils for Herod and, in return, receives Jokanaan’s head on a silver platter. When it was first written, the play was banned in Britain on account of its (allegedly) blasphemous and pornographic content.

I had not previously read the play, but I do know the opera by Richard Strauss, which is based closely on Wilde, though with cuts in the text to suit the music: I have an excellent recording, with Cheryl Studer in the title role and a full multilingual libretto so I can follow what is being sung; and I have also seen the opera live on stage. So I had some idea of what to expect, not least Wilde’s intentionally simple, mannered, repetitive words, and I wasn’t shocked by the dénouement, when Salomé gloats over the severed head and ultimately kisses its lips. This is a sufficiently transgressive scene still to be quite shocking if you are not prepared for it.

John did not know either the play or the opera, but he had read the reviews. So he knew one thing which I didn’t: that in this production Salomé is played by a man. I was quite startled when I realised this was the case. However, I was quickly won over by an outstanding performance from Matthew Tennyson, as Salomé. His stage movement was fluid, his presence androgynous, his manner somewhat (but not crudely) camp, by turns cajoling and petulant, swinging in an instant from infatuation to cruelty. If this had been a male role, it would have seemed a gross parody of a certain kind of ostentatious gayness; but here it fitted perfectly.

Whether it makes dramatic sense for Salomé to be male is another question. The moments in the play when Salomé is explicitly stated to be Herodias’ daughter feel awkward. When at the end of her dance Salomé is fully nude, even drunken Herod can surely see that she is in fact a man. Of course this is not a naturalistic play, or production, but these incongruities are hard to wish away. You can, however, see what director Owen Horsley is trying to achieve: partly referring to Wilde’s own ambiguous sexuality, partly reinforcing the transgressive nature of the plot and restoring any shock value that may have been diluted over the years since the play was first produced. In the theatre programme, Horsley says he is trying to introduce a reference to gay politics and the acceptance of gay lifestyles, but this seems unnecessary to me and (with one exception, discussed later) does not intrude into the production. On the whole I do not think that Salomé as a man makes much sense, but Tennyson is so good that it doesn’t matter.

At any rate, when Salomé’s shrewish mother Herodias and her brutish, drunken stepfather Herod are introduced, you can see at once how her personality has been distorted. Salomé is not a story about abusive parenting, but in this production it has a ring of psychological truth. Strauss’ opera focuses more strongly on Salomé herself, editing out much of Herod and Herodias (though it gives more attention, partly for reasons of musical contrast, to Jokanaan). In Wilde’s original, Herod is a much more significant figure: a classic study of the insecure tyrant, craving his overlord Caesar’s approval, glorying in the flattery of his toadies, alternately defiant and troubled in the face of omens and prophecies, but gloating over his enemies and lustful for his stepdaughter. It is a gift of a role, the only danger being how easily it can become ridiculous. We must remember that Herod is not just a lustful drunkard, but a powerful, dangerous man. Matthew Pidgeon, playing Herod, brought out the drunken caprice without ever quite going over the top.

The third corner of the triangle is represented by Jokanaan, played here by Gavin Fowler. At the start of the play an open hatch at front stage represents the cistern in which Jokanaan has been imprisoned and from which his (amplified) voice boomingly emerges. This seems a rare mis-step, since despite the amplification Jokanaan’s words are not always audible. Later in the play Jokanaan makes his ominous pronouncements from high in the wings of the theatre: again not very naturalistic, since he is supposed to have been returned to the cistern, but perhaps emphasising the doom which is closing in on Herod’s court. I confess that I did rather miss Strauss’ music for Jokanaan, which is assertively diatonic, in dramatic contrast to the lush chromaticism of the rest of the score. In this production Jokanaan seems under-developed, which I think is more down to the director than to the actor or the author.

But for me, and I suspect for many others in the audience, the shadow of Richard Strauss constantly hangs over the play. His opera is, I should guess, a good deal more often performed than Wilde’s original: it is an unquestionable modern masterpiece and revived regularly in opera houses all round the world, whenever they can find a singer capable and willing to play the demanding title role. Owen Horsley must have been aware of this risk and the music for the production is very deliberately not Straussian. Unfortunately it is also not very good or appropriate. To me it sounds like a pastiche of Freddie Mercury and Queen. This is clearly not an accident, since Mercury was famously bisexual; Horsley’s agenda of gay awareness does intrude here.

I don’t think this is just a matter of disliking Queen’s music. But theatre music done well can underpin what you see on stage. This music, consisting in part of songs performed on stage by a singer with a microphone who is completely separate from the dramatic action, does not underpin, but intrudes. It forces us into a completely different world from that of the play. It doesn’t belong.

I should in fairness acknowledge other, better aspects of the show. The opening scene can feel quite disjointed as, though it introduces the setting and theme, it consists of three different overlapping conversations, intercut with one another. Here, thanks to clear diction and effective lighting, it comes across clearly. When we meet Herod, he is accompanied by a crowd of sycophants; later in the play, they also fulfil the role of Jewish religious leaders, quarrelling over trifles. Their Jewishness is not emphasised, but their disputes add a leavening of humour which is well brought out. One of the actors is the spitting image of Michael Gove. I wonder….

——————–

The Tempest

20 July 2017

Last Friday John and I went to the Barbican theatre in London to see the RSC’s latest production of The Tempest, with Simon Russell Beale as Prospero. We missed it at Stratford, which may in fact have been for the best, as I shall explain. But several friends had told us it was a must-see production, so we were glad when it transferred.

We couldn’t recall the last time we came to the Barbican Centre, which is the performing arts complex opened in 1982 by the City of London and funded by the City Corporation. It has a fine concert hall, two exhibition spaces, and other versatile spaces as well as the theatre: the London Symphony Orchestra is now resident there. When the Centre was first opened, the RSC used it as their London base, but that arrangement was controversially – and acrimoniously – terminated in 2002 during Adrian Noble’s brief tenure as the RSC’s Artistic Director. Fortunately Noble was removed before he could do too much other harm, but it took more than a decade for the breach between the RSC and the Barbican to be repaired. In the meanwhile the RSC has had to hunt for other London venues when it wants to transfer its Stratford shows. So it is good news that the RSC is back, although I am not clear whether the arrangement is intended to be permanent.

In the meanwhile, the RSC has radically reconfigured its main theatre at Stratford, from a traditional proscenium layout to an apron stage, with the audience on three sides of the action. It is in many ways an improvement: the new layout means that the seats furthest back from or above the stage are much closer than they used to be, and the rake, which enables those in seats further back to look over the heads of those in front, is no longer a problem. It has also had an effect on productions, since with an apron stage it is necessary to manage with a bare-bones set, so that sight lines from the sides are not obscured. As this is akin to how Shakespeare and his contemporaries’ plays were originally performed, it is not usually a problem, but when shows transfer they have to be adapted for the proscenium stage which is almost ubiquitous in London theatres. The Barbican is no exception, though it is a large theatre with an unusually broad stage.

Directors at Stratford do not seem, thus far at least, to have had any difficulty finding interesting ways to use the theatre in its new layout. But this production of the Tempest was something quite out of the ordinary, with a range of lighting effects that I had not previously seen. The RSC website and the programme for the show proclaim that it was developed in partnership with Intel, the tech giants who manufacture computer chips (and probably other stuff too that I don’t know about). The fruits of this co-operation were visible throughout the play.

The set for the play consists of a wooden framework, with horizontal planks and curving vertical stanchions, at either side of the stage. The overall effect is to suggest the hold of a large wooden ship. At Stratford, they presumably cleared, and used, the whole backstage area, some of which is not visible from either side of the apron stage. But at the Barbican there were no problems with sighting.

The set for the play consists of a wooden framework, with horizontal planks and curving vertical stanchions, at either side of the stage. The overall effect is to suggest the hold of a large wooden ship. At Stratford, they presumably cleared, and used, the whole backstage area, some of which is not visible from either side of the apron stage. But at the Barbican there were no problems with sighting.

The set enabled the shipwreck scene which opens the play to be done more effectively than usual – we could scarcely hear or see the actors above the sound and lighting effects which represented the storm. No doubt Intel can claim their share of credit. Later in the play, the shipwrecked sailors find a feast apparently laid out for them, only for it to burst into flames as they approach. This was again done purely with lighting, but the flames were extraordinarily realistic, and the effect was truly startling even if you were expecting it. Other lighting effecs were equally spectacular, as for instance in the forest scene below.

But Intel’s main contribution came in the presentation of Ariel, the fairy sprite who assists Prospero. Ariel was played by Mark Quartley, a member of the Imaginarium Studios which specialise in motion-capture performance. The Studios were founded in 2011 by Andy Serkis, who was memorable as Gollum in Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings. Motion capture involves placing sensors all over the actor’s body and using the feed from those sensors to construct an image, which can then be digitally manipulated – changing colour, stretching and bending, turning or inverting. There is an excellent article about how motion capture was used in The Tempest at https://www.creativereview.co.uk/tech-comes-to-the-tempest-in-new-rsc-production.

But Intel’s main contribution came in the presentation of Ariel, the fairy sprite who assists Prospero. Ariel was played by Mark Quartley, a member of the Imaginarium Studios which specialise in motion-capture performance. The Studios were founded in 2011 by Andy Serkis, who was memorable as Gollum in Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings. Motion capture involves placing sensors all over the actor’s body and using the feed from those sensors to construct an image, which can then be digitally manipulated – changing colour, stretching and bending, turning or inverting. There is an excellent article about how motion capture was used in The Tempest at https://www.creativereview.co.uk/tech-comes-to-the-tempest-in-new-rsc-production.

A complication of this approach was that the image cannot (yet) speak, or interact with the stage actors, and therefore at times there were two Ariels on stage, the actor and the digital image. You might think this would ruin the illusion, but somehow it didn’t. Perhaps we implicitly accepted that the duality has been caused by Prospero confining the spirit Ariel into an earthbound form. In any case, Mark Quartley gave a fine performance: he managed to suggest chafing against his confinement, yet at the end of the play, when Prospero releases him, he also conveyed a real sense of regret.

A complication of this approach was that the image cannot (yet) speak, or interact with the stage actors, and therefore at times there were two Ariels on stage, the actor and the digital image. You might think this would ruin the illusion, but somehow it didn’t. Perhaps we implicitly accepted that the duality has been caused by Prospero confining the spirit Ariel into an earthbound form. In any case, Mark Quartley gave a fine performance: he managed to suggest chafing against his confinement, yet at the end of the play, when Prospero releases him, he also conveyed a real sense of regret.

Which brings us back to Simon Russell Beale as Prospero. He was outstanding: vengeful, regretful, wise, petulant. He spoke the verse beautifully, so that both the poetry and the meaning were transparent. John and I have seen him in several roles now, including Sir Harcourt Courtly in London Assurance, Benedick in Much Ado, Timon of Athens and Leontes in The Winter’s Tale; but Prospero fitted him perfectly. Last time we saw The Tempest, Prospero was played by Patrick Stewart, a fine actor but with a rather stern stage presence. Russell Beale was in complete contrast and you could not but sympathise with the mixed feelings of victimhood and guilt which he conveyed.

John sometimes says, of that great actor Judi Dench, that these days she simply plays herself. I don’t think he means it unkindly, but it is true that she has such a well-established persona that it’s hard to break out. I do wonder whether Russell Beale is in danger of going the same way. In his early career he made a point of playing a wide variety of roles: his Hamlet and Lear, both for the National, won plaudits from critics and audiences alike. But there is a particular sensibility to his acting and, while it fitted Prospero perfectly, I’d like to see him do something quite different, with a director who makes different demands.

Russell Beale, and Quartley in his different way, were both outstanding: but the production was a triumph for the whole company. My only, minor, quibble might be that Jenny Rainsford as Miranda was a bit more knowing than she has any right to be. But Joe Dixon made Caliban both brutal and pathetic, especially in his scenes with the comic pair Trincolo (Simon Trinder) and Stephano (James Hayes). It sometimes seems as if Shakespeare’s comic episodes have dated less well than other parts of his plays, but in recent productions the RSC has shown that this need not be a problem, and on this occasion Trincolo and Stephano were genuinely funny without being at all laboured.

The production also included the full wedding masque, complete with gorgeous costumes and heavenly singing, which Prospero conjures up to celebrate his daughter’s betrothal. The masque was an important part of court performances in Shakespeare’s time, and was an opportunity for extravagant display, but in The Tempest modern directors often shorten or leave it out altogether as it is a distraction from the story. However, its rather showy nature fitted well into this production and was the opportunity for some more spectacular stage effects.

It has become commonplace to interpret Prospero’s speech “Our revels now are ended…” as Shakespeare’s farewell to the theatre, and directors often overlay this thought on to their productions. There was none of that here. This Tempest was presented purely as an entertainment of words and music, light and sound, pathos and joy; and was all the better for it.

——————–

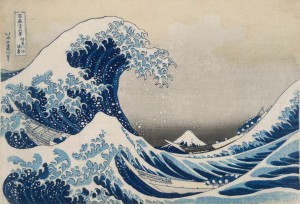

Beyond the Great Wave

16 July 2017

Apart from our two theatre visits this weekend, John and I also went to see the exhibition at the British Museum, Beyond the Great Wave, which features the work of the Japanese artist Hokusai, mostly from the final 30 years of his life. Apart from the crowds – most of the paintings are quite small, and the exhibition is very popular – it was brilliant. Beyond the Great Wave has my highest recommendation if you are the least bit interested in pictorial art, or in life and culture of Japan. But book now: admission is controlled and many time slots are already full.

Hokusai lived to the age of 90. According to art historians, and on the evidence of this exhibition, his art improved with age. If you wish to cavil, you might point out that his daughter, who from other work is known to have been a considerable artist in her own right, assisted Hokusai towards the end of his life, and it is possible that his final paintings owe as much to her as to him. Regardless, he had an extraordinary late flowering at an age when most are hanging up their tools.

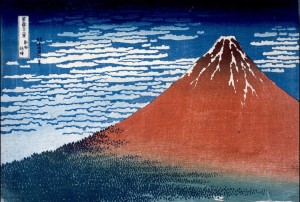

Hokusai’s most famous picture is, of course, the one known as The Great Wave. Not for nothing has it become a global icon. But the exhibition showed me at least three things about this picture that I hadn’t known. First, that is not its proper title. The picture comes from a series called 36 Views of Mount Fuji, and its title is Under the Wave off Kanagawa. In the picture you can see a tiny image of Fuji which is almost completely framed by the towering wave. Hokusai cannot have been unaware of how the eyes are drawn first to the wave, then to the boats and only thirdly to the mountain: it is a kind of playfulness that is repeated many times through the exhibition.

Second, its use of perspective is revolutionary in Japanese art. Previously the convention had been that more distant objects were depicted higher up the image. Hokusai learned the use of perspective from Western models and adopted it in his own work. We take the use of perspective for granted, and tend to wince when it is not properly applied, or to think it revolutionary when perspective is deliberately distorted or disregarded. For Hokusai it was the other way around.

Third, though I knew that this picture is in fact a print from a woodblock, I had not properly understood all the implications. If you look closely you will see there is almost no shading, just areas of uniform colour. Only five colours are present: white, grey, dark blue, light blue and a sort of mid-blue which I suspect is a mixture of the other two. (I believe there may be a sixth colour, very pale orange, for the boats, but it is not easily discernible in this reproduction.) The pink in the sky is not, I think, authentic. Only in the grey background is there perceptible shading in colour. Hokusai achieves his effects not by shading but by skilful juxtaposition of areas of related or contrasting colour. This is in complete contrast to Western oil painting: compare The Great Wave’s restricted palette with the intoxicating range of greens in Rousseau’s painting Surprised! which I featured in my blog on 4 July.

I had also not properly understood that Hokusai’s original no longer exists, as it was destroyed in the creation of the first woodblock. That block was used to make a set of prints, or possibly more than one set; from those prints new blocks may then be made; and so on. The picture may thus change subtly over the generations, not just in outlines but in colouration. For instance, experts believe that one picture on show, popularly known as “Red Fuji,” may well have originally been coloured a much paler pink. The curators do not state, and perhaps don’t know, how many generations of blocks have passed before each picture in the exhibition was printed. I should think that these are early prints, as extravagant care is being taken to protect them, but the idea of a Hokusai “original” is clearly moot.

The exhibition includes two short videos which show how a woodcutter prepares he woodblock by carving along the lines of the original drawing, thus reducing it to shreds, and how colour is then applied to the block. Unfortunately the videos don’t go on to show how the successive colours are applied or how the shading, which is visible on the grey horizon of The Great Wave and in other skies and mountainscapes, is achieved. I have come away wanting to know more.

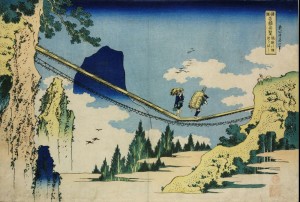

Hokusai apparently drove his woodcutters to distraction with his technical demands, and when you look at the pictures you can easily understand how they must have felt. But there was method in his madness. Western painters needed to find wealthy patrons for their work, but Hokusai’s prints could find a wider market, either as single items or bound together into books. After the 36 Views of Mt Fuji, he published other series such as Unusual Bridges and A Tour of the Waterfalls. In some respects the Japanese idea of the picturesque is evidently not so different from our own. The Bridges pictures in particular (see examples, right) show a considerable variety and illustrate Hokusai’s versatility even with this limited medium.

Hokusai apparently drove his woodcutters to distraction with his technical demands, and when you look at the pictures you can easily understand how they must have felt. But there was method in his madness. Western painters needed to find wealthy patrons for their work, but Hokusai’s prints could find a wider market, either as single items or bound together into books. After the 36 Views of Mt Fuji, he published other series such as Unusual Bridges and A Tour of the Waterfalls. In some respects the Japanese idea of the picturesque is evidently not so different from our own. The Bridges pictures in particular (see examples, right) show a considerable variety and illustrate Hokusai’s versatility even with this limited medium.

But he was not confined to painting for woodblocks. He also produced paintings on silk bound into hanging scrolls, of which the exhibition has a fair number; and when some high-quality “old Dutch paper” (as the catalogue has it) came into his hands, the work he produced shows what he could do when not constrained by what the woodcutters could reproduce. Look for instance at the picture Year-end Accounts, which has the same delicacy of drawing and eye for detail as his other work, but in addition makes most skilful use of shading to bring out the folds in the fabric of curtains and clothes, and the grain in the wooden panelling.

This picture also illustrates the range of Hokusai’s subjects. Much Western painting up to the nineteenth century has a fairly restricted range of subjects: portraits and religious images, still lifes and landscapes, maritime scenes and public occasions. (This is of course a gross generalisation – think of Turner! – but you only have to go round the National Gallery, the Louvre or the Prado, to see what I mean.) Hokusai paints anything he sees, or in some cases imagines. There is a good deal of daily life in his pictures.

He also has a sly sense of humour, as shown in the picture Ejiri in the Suroka Province. The trees are bent by the force of the wind, which has blown away a pile of sheets of paper. One figure is clutching his hat; another hat is in mid-air. This picture (another woodcut, by the way; the carver must have had a field day with this one) can scarcely have been posed, yet it is wonderfully evocative.

He also has a sly sense of humour, as shown in the picture Ejiri in the Suroka Province. The trees are bent by the force of the wind, which has blown away a pile of sheets of paper. One figure is clutching his hat; another hat is in mid-air. This picture (another woodcut, by the way; the carver must have had a field day with this one) can scarcely have been posed, yet it is wonderfully evocative.

Another feature of Hokusai’s work I hadn’t previously known is his marvellously attentive and detailed depiction of plants, animals and birds. We particularly liked his eagle with its knowing expreession. All his creatures seem alive. And look too at the phoenix below: this reproduction does it less than justice, but you can still admire the colours and the beady eye. The phoenix was painted as the model for a temple ceiling which still exists today.

Another feature of Hokusai’s work I hadn’t previously known is his marvellously attentive and detailed depiction of plants, animals and birds. We particularly liked his eagle with its knowing expreession. All his creatures seem alive. And look too at the phoenix below: this reproduction does it less than justice, but you can still admire the colours and the beady eye. The phoenix was painted as the model for a temple ceiling which still exists today.

At the end of the exhibition John and I indulged ourselves in the shop. Art exhibitions usually end with a shop selling souvenir goods, not always of much interest or value; but those at the British Museum tend to be better than most. The exhibition catalogue was an eye-watering £35, but we found another book with high-quality colour plates for a more reasonable price. We also bought each other a mug with a Hokusai design, John bought a print of the phoenix picture and a set of postcards which he will no doubt paste into one of his scrapbooks or albums, and I bought several other things which I won’t enumerate as they may find their way into Christmas stockings.

——————–

Ink

16 July 2017

Beware : spoilers

(Note for Australians: the Almeida and Orange Tree are small studio theatres which characteristically stage a wider repertoire than you will find in the major London venues, though their best productions sometimes transfer to the West End. The Almeida is in fact in Islington, and the Orange Tree in Richmond.)

John and I do not go to see new plays all that often. Many of our best theatrical experiences have been with revivals of neglected plays like Granville Barker’s Waste or Racine’s Berenice. If directors think an old play is worth reviving, it usually has at least something going for it. But new plays are much more of a lottery. Theatre tickets are too expensive for us to take a punt on new work unless there is some specific draw – most likely a writer, or director, or company, whose work we trust.

We do sometimes go to see new plays when the reviews are in. But the reviews are not always reliable. We went to see Alastair McDowall’s Pomona, when it transferred to the National Theatre, on the strength of the reviews it received when first produced at the Orange Tree. It was execrable – crass and incoherent; worse, it squandered a startling original premise which is never developed as it might have been.

Still, when we went to see the Almeida’s production of James Graham’s new play Ink, our hopes – well, mine at least – were good. We have a high regard for the Almeida and its artistic director Rupert Goold, whose production this is. And James Graham’s previous play, This House, which I saw when it was staged at the National a couple of years ago, was riveting. He had good material to work with: the story of how the Callaghan government limped through the late seventies despite having no Parliamentary majority. But he made the most of it.

The great success of This House was that it didn’t take sides, but did take the lid off how the Whips Office struggled to keep the Government afloat almost from night to night. (In those days, not so long ago, most Parliamentary votes took place in the evenings.) So, when I saw that Ink, his new play at the Almeida, would be about the early days of the Sun newspaper after it was taken over by Rupert Murdoch, I hoped that Graham would be able to pull off the same trick.

Well, I am pleased to say that, when we went to see Ink yesterday, John and I were not disappointed. It has the same behind-the-scenes quality as This House, showing the human motivations and drama behind the public events.

Graham is careful not to load the dice. What we see is not the present-day Rupert Murdoch, the media tycoon who is hated and feared in equal measure by competitors, politicians and victims, but Murdoch as he then was, the Australian outsider determined to break into the elitist cartel of British newspaper owners and editors who talked down to the common people when they didn’t ignore them altogether. He had a vision of how this could be done, and in Larry Lamb, the new Sun’s first editor, whose enlistment is the first scene of the play, he found an able accomplice. More than able: by the end even Murdoch, in this account, seems just a little alarmed by the beast he has helped to unleash. One review I have seen compares Murdoch and Lamb to Mephistopheles and Faust, but to me it seemed more like Frankenstein and the monster. Only with hindsight does Murdoch become the Devil.

There is an undeniable excitement to the first half of the play as we see Lamb assembling his team of writers and editors through a mixture of flattery, bribery and intimidation; how he leads, cajoles and drives them to adopt a different ethos in which there is no place for how things used to be done; how the first edition is produced against an impossible deadline, and how its immediate success sends Fleet Street rivals, notably Hugh Cudlipp at the Daily Mirror, into a panic. After the interval the pace slows a little, and we get two episodes from the Sun’s first year: the kidnapping and presumed murder (a body was never found) of Muriel McKay, wife of the deputy editor; and the introduction of the Page 3 girl.

I had completely forgotten the (true) story of the kidnapping: but Graham uses it to show Lamb’s drive and his insensitivity, as he splashes the story across his newspaper. It is a clever foreshadowing of how the Sun would go on to trample over all sensitivities, regardless of harm caused, in the years ahead. As for the Page 3 girl, there is a long, awkward scene in which Lamb gradually gets round to telling the model, Stephanie Rahm, what he wants. It is well done, but does not feel quite true to the character of Lamb, as if this was an intrusion from a different play. However, the climactic three-way confrontation after publication between an unapologetic Lamb, a faintly horrified Murdoch and a distraught Rahm, is dramatic and very well handled.

In one brilliantly choreographed sequence we see all the stages involved in turning the journalists’ copy into print. These were the days of the print unions, where the closed shop still ruled and jobs were handed down through families. All this was later overturned by Murdoch with his move to Wapping and adoption of new technology; that story lies outside the play’s time frame, but Graham ingeniously shows its genesis.

The well-designed sage set has press room clutter upstage and, at the top, a ledge large enough for a secondary acting space. In the climax before the interval we see Cudlipp and his executives in conference on this ledge, panicking at the threat to the Mirror’s dominion, while Murdoch, Lamb and Sun staff celebrate their early success downstage. Good use is made of the trapdoors, enabling various large props – ranging from a restaurant table to a printing machine – to be easily hoisted into centre stage and removed while action continues round them. Other props such as billboards are cleverly deployed, notably a slate on which daily sales of the various tabloids are displayed as a horizontal bar-graph. We see the Sun’s sales increase, and are left to judge for ourselves at what cost.

The well-designed sage set has press room clutter upstage and, at the top, a ledge large enough for a secondary acting space. In the climax before the interval we see Cudlipp and his executives in conference on this ledge, panicking at the threat to the Mirror’s dominion, while Murdoch, Lamb and Sun staff celebrate their early success downstage. Good use is made of the trapdoors, enabling various large props – ranging from a restaurant table to a printing machine – to be easily hoisted into centre stage and removed while action continues round them. Other props such as billboards are cleverly deployed, notably a slate on which daily sales of the various tabloids are displayed as a horizontal bar-graph. We see the Sun’s sales increase, and are left to judge for ourselves at what cost.

The acting is uniformly excellent. Bernie Carvel as Murdoch is far from a lookalike, but he brilliantly conveys the man’s vision and drive, someone who can switch between cajoling and confrontation in an instant. The Australian accent is present if you listen for it, but subtly done. There is a brilliant scene of a TV interview in which a nimble Murdoch blocks every thrust and manages some neat counter-attacks of his own against the interviewer’s easy assumptions.

Richard Coyle as Lamb conveys the same drive and ruthlessness, but comes across much more as a workplace bully. Early in his career Coyle was a screen heartthrob (for instance as John Ridd in BBC mini-series of Lorna Doone, back in 2000) but here there are elements of seediness and desperation in the performance: passed over for promotion at the Daily Mirror, he is now on his last chance, and he knows it.

The rest of the cast of thirteen are made to work hard, most of them taking several roles, but I was particularly taken by David Schofield as Hugh Cudlipp, the Welsh working-class boy made good. He has the play’s single most resonant line when he warns Lamb that if you pander to people’s basest instincts, you create an appetite you can never satisfy. Pearl Chanda also comes to the fore in the second act: putting on a sassy, streetwise front in her interview with Lamb, then despairing and frantic when she realises how she has been exploited, as we know so many others will be in the years to follow. A lot of the play is like this, telling a simple story which is nonetheless full of forward echoes: in this respect it outstrips even This House.

I did not think the second half of Ink, when the first chickens come home to roost, had quite the impact of the first half. The pace is down, and the tone is more uneven, though there are still some fine moments. And I regretted that the time span did not extend to Wapping: what would Graham have made of that? But it is still a fine play. A West End transfer is planned, and if you haven’t already been to see it, the effort is well worth while.

——————–

Ministry of Flat Walks 02 : Haverthwaite to Greenodd

10 July 2017

To follow this walk, open another tab on your browser and input this web address: http://www.streetmap.co.uk/idld.srf?x=333395&y=482715&z=115&sv=333395,482715&st=4&ar=Y&mapp=idld.srf&searchp=s.srf&dn=688&ax=333395&ay=482715&lm=0.

John and I tackled this walk on Saturday. We have done it twice before, and I think John has done it at least once when I haven’t been with him. It is one of my favourite walks as it is almost completely flat but also a good length, about 5 miles I should say. However, it can only be done when the weather has been dry, as there are some sections that can become extremely boggy. So it is essentially a summer walk.

John parked the car at Low Wood (near the right edge of the map). The river which flows across the map from right to left is the Leven, and just south of the bridge where the road from Cark to Haverthwaite (B5278) crosses the Leven you can just see a lane turning to the west, parallel to the river. On the map, the lane is partially obscured by the line of green dashes denoting a public right of way. Here, by the river edge, is a parking place for three or four cars. We have also in the past used a parking place by the side of the B5278 just north of Haverthwaite village, along the straight section before the road turns to meet the A590: there is more room here if the Low Wood spaces are all taken.

Road bridge over the River Leven at Low Wood. This photograph was taken from near our favoured car parking space.

The least interesting part of this walk comes first, as you follow the B5278 into Haverthwaite village, just past the old railway bridge. The bridge itself has been taken down, but the piers on either side of the road are still in place. Just to the left here, before you pass the railway bridge, is the Levens Valley Sports Club, where there is an elaborate children’s playground and a cricket field. Levens Valley play in the lowest division of the Westmorland League (see blog on 15 May): they have a pretty ground, but with no sightscreens, so batting there must be quite challenging. A match was in progress on Saturday and we stayed to watch a few overs: the bowlers were definitely on top.

Shortly beyond the old railway bridge, where the B road swings to the right, a lane leads straight ahead between the houses. You follow this for a short distance and then turn left down a footpath in front of another house. This path is somewhat overgrown, with brambles, nettles and thistles to obstruct your passage. It runs along the edge of a field and then climbs briefly over a spur of rising ground before dropping down to a gate at the edge of reedy pastureland. When you pass through the gate, ahead and to your left is a rocky outcrop with trees. On the map, the path here is shown as following the hedge to the right (north), but that isn’t recommended as it is very reedy and boggy. Instead, you climb over the rising ground (not steep, easily manageable) in the middle of the field, but keep the rocky outcrop to your left. On the far side of the pasture is a gate for a farm track (also shown on the map). You follow this track and turn left a few yards along where the track crosses the path.

The rest of the walk is pretty easy to follow. The path follows the raised bank at the side of the river, past the point where Rusland Pool flows into the Leven, and turns southward to join the line of the old railway just to the east of its bridge over the Leven. The bridge is still in place and in serviceable condition: some of the ironwork bears the mark BSC, presumably for British Steel Corporation, which means it was erected after the steel industry was nationalised in 1967, after the line was closed. How this came about, I have no idea. I believe John has attempted to follow the line of the railway back towards Haverthwaite, but this section of the route is now in private hands and protected by fences and hedges. A pity.

I can just barely remember travelling with Grandma and Grandpa on this line from Ulverston up to Lakeside, where we boarded the lake “steamer” for the round trip to Bowness and Ambleside. I can also just remember the station at Greenodd (closed some time earlier) and the railway viaduct across the Leven, both of which were still in place when Mum and Dad bought their cottage at Woodgate in 1966. Within a few years, however, the viaduct and station had been demolished to make way for the new road bridge over the River Crake, thus putting paid to any prospect of the line being reopened. Even the iron piers of the viaduct have gone.

The path follows the line of the railway to Greenodd where there is a new footbridge across the Leven into the village. This is one of the places where Dad and David, sometimes with John in attendance, used to go fishing, and to dig up lugworms as bait. Dad’s painting of David and John with fishing gear, which has pride of place above the sideboard in my living room in Oxted, shows this scene.

The footbridge is a good vantage point for admiring the scenery, whether you are interested in the Lake District hills, visible on the horizon to the north behind the trees which line the Leven valley, or the salt flats to the south where the river flows into Morecambe Bay. The waters here are tidal; on this occasion the tide was low but there was a family of eleven geese proceeding in a stately formation southwards, under the bridge, towards the sea.

We had started late on the walk and by now it was past six o’clock, so our return to Haverthwaite was a bit of a route march; the walk is more pleasant if you have more time. From the bridge at Greenodd a footpath leads eastwards across two pastures, with reeds and thistles, before it joins a metalled road coming in from the right. This road is a cul-de-sac, serving only Mearness Farm, a few hundred yards south, and Lady Syke Farm, to which another lane branches off to the north a little further on.

Along the way you pass Roudsea Wood, which is a national nature reserve and a site of special scientific interest. If you input “Roudsea Wood” into Google you should get a link to a pdf copy of a very informative Natural England booklet about the site. John and I really ought to obtain a permit for a visit: permits are required, but free, and John would surely find lots of interest for his camera.

The metalled lane leads all the way back to Haverthwaite, but near the end a short cut across the water meadows is possible as you are approaching Low Wood. This is another section of the walk which can become seriously waterlogged, but on Saturday it was fine. We eventually got back to the car some time after seven o’clock: a fifteen minute drive home, and dinner was eventually ready at half past eight. Next time we do this walk, we must allow a whole afternoon.

Thanks to John who provided two of the photos for this blog.

——————–

Ministry of Flat Walks 01 : Levens Park

10 July 2017

I have never been terribly fond of walking uphill, as it doesn’t take much for me to become uncomfortably short of breath. But in the last 15 months I have found it more and more difficult, which is I think due less to the passing years than to the hormone implants I am being given as part of the treatment for prostate cancer (see blog on 10 February).

So, for when I am staying at Cark, it has become more important than ever to search out walking routes which, if not entirely flat, are at least manageable. Most of the well-known walks in the Lake District are quite hilly, but with a bit of research and ingenuity we have found several which are flat enough for me to enjoy, and I plan to write about some of them here.

I’d like to illustrate my blogs with clips from the excellent Streetmap website which uses the Ordnance Survey 1:25,000 and 1:50,000 maps as its data source, but so far I haven’t been able to work out how to do it. The difficulty may be intentional, as the OS no doubt wants to protect its product, but I expect there is a workaround if I can find it. Anyway, for the meanwhile, to follow today’s walk you need to open another tab on your browser and input this web address:

John and I tackled this walk on Sunday. It is not in fact a flat walk at all, but the hills are gentle and brief enough to be manageable. In length it is a bare 4 miles, but as there are sections where I have to go quite slowly it feels a bit longer.

In the centre of the map you can see Levens Hall and Levens Bridge, both marked in antique script. The A6 crosses the River Kent on Levens Bridge and just north of the bridge is a junction where a spur leads off the A6 to join the A590 westbound towards Ulverston and Barrow. Just north of this junction is a layby where John parked our car. It’s a popular parking spot, but there is plenty of room.

On this map the footpaths are marked as lines of pink dots, denoting public rights of way. The line of the walk starts immediately north of Levens Bridge where a marked footpath leads north east through the parkland away from the road. Levens Park is part of the Levens Hall estate which is privately owned by the Bagot family, and in the park they keep a herd of rare breed Bagot goats (some connection, surely – Ed). It is also a deer park; the deer are shy, but on previous visits we have been able to spot them, usually in the shade under the trees. However, on this occasion they were elusive.

At this point the path consists of a mown lane through the high grasses of the meadow. It was quite amusing to watch John stalking the small Meadow Brown butterflies, whose habitat this is, through the grasses; but I must say that his patience was rewarded with at least one really good photograph – see right. He has become a patient and skilful photographer.

The path winds its way upwards to the far side of the park where there is a locked gate and a stile leading into a minor road. You cross the stile into this road and turn right, past a couple of well-appointed cottages and down towards the river and the A590 dual carriageway. The road comes to a dead end, but a path continues down a set of steps and along a kind of gallery, under the A590 while overlooking the River Kent. On the far side, the minor road resumes – I suspect it was severed when the dual carriageway was built – past more cottages to a junction and a road bridge over the river.

At this point you can cross the bridge and turn right for a shorter walk, but John and I continued along the road by the west side of the river for another half mile or so, turning right at the first junction and ignoring the next turning to the left, which leads uphill to the farm and craft shop at Low Sizergh Barn (Low Sizergh is marked on the map). We recently discovered this shop and now visit it regularly, as John can buy Ennerdale Darkest beer there which has rapidly become one of his favourites. The shop also has excellent ice cream and a good display of cheeses, honeys and jams, biscuits and chocolate. But halfway round a country walk is not, perhaps, the wisest time and place to go shopping, so on this occasion we resisted the temptation.

The riverbank on this side is wooded, so after the turning for Low Sizergh you need to keep your eyes open for the footbridge. It is a suspension bridge and a warning notice states that the maximum load is 25 people, but doesn’t say anything about people who deliberately bounce around to make the bridge sway, as John mischievously delights in doing.

Anyway, you cross the bridge and turn right, heading back southwards. You follow this path, which quickly becomes a minor road, back to the road bridge where you could have turned earlier. Now you continue along this road up a slight hill and across the dual carriageway on an overbridge. Just beyond this bridge is a gate on the right hand side which leads back into Levens Park, on the other side of the river from where you started.

You still have the best part of a mile to go, but from here the walk is pretty straightforward, and a least you have left the tarmac behind. You follow the marked path, initially along an avenue of trees, then branching out through the meadow by the side of the river. This was a good place for John to indulge his favourite pastime of throwing stones into any open water that he walks past, and as the river is 20 feet or more below the level of the path he was able to make some good splashes.

It was also on this side that we found the Bagot goats, sitting comfortably in the middle of the footpath. They seemed quite docile, but the males (I presume they were the males) have the most ferocious-looking horns; if they took a dislike to you, watch out! A couple of walkers just ahead of us made a careful detour into the meadow so as not to disturb the beasts, and John and I followed suit. At least they didn’t object to being photographed.

The path comes out at another stile on the main road immediately south of Levens Bridge, within sight of where our car was parked. What with hills, goats, butterflies and photography, the walk took us about two hours. A good way to spend a sunny Sunday afternoon.

Thanks to John who provided all the photos for this blog.

——————–

Green

4 July 2017

A few days ago I decided that I had had enough of staring at my computer screen. I switched off the PC and took the car out for a drive.

John is very rude about my car, which he knows I do not choose to drive very often. He says I neglect it and that as a consequence it is entombed in spider webs and rats’ nests. Which isn’t true. But it is true that I don’t generally enjoy driving very much. There is too much traffic, at least in the South East where I live; too many people, in too much of a hurry, and thus too frequent traffic queues. Last time I drove to visit Michelle and Andy in Kingston, it took me nearly half an hour just to reach the M25 junction which is barely three miles away from my garage door, and the full journey lasted an hour and a half. I would have reached Kingston as quickly by train even though that involves travelling all the way up to Clapham Junction, waiting there for a connection in the opposite direction, and a 10-minute walk from the station at Surbiton.

So I rarely go out just for a drive. I like to have a purpose in mind. On this occasion I decided to visit two farm shops that I know: the Flower Farm at Godstone, a couple of miles away from here, and Painshill Orchard which is in the deep Sussex countryside some way beyond Edenbridge..

It is 20 years or more since I first visited the Flower Farm, with Mum and Dad when they were staying with me at my old house in Eastlands Way. (I moved down the road a few hundred yards to my current home, nearer Oxted town centre and the park, in 2001.) At the time the farm shop consisted of a simple pick-your-own operation in a large field just off the main road, with a wooden shack where punnets were handed out and the fruit you had collected was weighed. I remember that we collected two large baskets full of the most beautiful raspberries, most of which I later froze, and which kept me going for a year or more.

But when I went back, on my own, a couple of years later, the place was in decline. The raspberry canes had been poorly tended and the fruit was sparse. After that I stopped going, and for some years the field lay fallow.

So I was pleased when, three or four years ago, driving towards Redhill, I found that a new sign had been erected with directions to a farm shop on the other side of the road from the old raspberry field. The shop has been established in what looks like an old farm building, and as well as fruit and vegetables (which are clearly not all locally grown) there are also fresh bread and cakes, beer from the local microbrewery, and fresh meat on offer. The vegetables are particularly good because they often include slightly unusual things such as yellow tomatoes or golden beetroot, though they are not cheap. There is also a tea room which I haven’t (so far) investigated.

This time, I thought I would look for strawberries and raspberries, because I have become very fed up with what the supermarkets have on offer: modern hybrid varieties which have clearly been produced for their hardiness rather than their flavour. I was very pleased to find that the Flower Farm has restarted its pick-your-own business, though in a different field. I filled two small baskets with raspberries and brought them home; they are delicious, far superior to the supermarket varieties. I confess I chose to buy ready-picked strawberries, though, as I didn’t fancy all the bending down. Besides, there were already several other strawberry-pickers at work.

Afterwards I drove on to Painshill. There is a very pretty, and not too heavily used, B road which runs south from Oxted across the heathland at Limpsfield Chart to Edenbridge, then onward between East Grinstead and Tunbridge Wells, across the Weald and through the Ashdown Forest, past the pretty village of Hartfield, towards Uckfield and the south cost between Eastbourne and Lewes. Painshill is on the edge of the Forest just before you get to Hartfield.

The road across the Chart passes under a thick canopy of trees, and it put me in mind of our return from Madrid when John and I admired the green British countryside after the ochre-yellows of Spain. Mum used to love the springtime when the trees first put out their new leaves and all the green seems bright and fresh. Today it’s early July and spring has turned to summer, but there is still a whole range of greenness to be enjoyed, if you care to look. In the English language we have, curiously, far more names for tints of red – crimson, scarlet, maroon, vermilion, cerise – than we do for green, yet it is surely green which is the colour of England.

The road across the Chart passes under a thick canopy of trees, and it put me in mind of our return from Madrid when John and I admired the green British countryside after the ochre-yellows of Spain. Mum used to love the springtime when the trees first put out their new leaves and all the green seems bright and fresh. Today it’s early July and spring has turned to summer, but there is still a whole range of greenness to be enjoyed, if you care to look. In the English language we have, curiously, far more names for tints of red – crimson, scarlet, maroon, vermilion, cerise – than we do for green, yet it is surely green which is the colour of England.

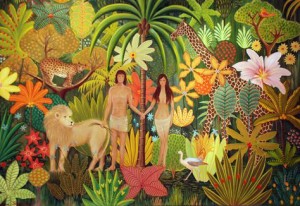

Perhaps it takes a painter’s eye to appreciate this. A few years ago John and I completed a jigsaw of Henri “Douanier” Rousseau’s painting Surprised! which gave us an entirely new appreciation of his mastery of colour. Rousseau understood green. There are hundreds of green shades in this picture: they help to give it life. The jungle of Rousseau’s imagination is nothing like the English countryside, but if you look at the countryside with Surprised! in mind you will see an equal range of greens, not just in the spring but at the height of summer too.

Surprised! is on view at the National Gallery. But a few years ago there was an exhibition at the Tate Modern of many more of Rousseau’s paintings. Now, the truth is that Rousseau was self-taught, and it shows: his paintings of human figures, especially portraits, are almost embarrassing, a bit like McGonagall’s “poetry”. But if you disregard his portraits and focus on the jungles and other landscapes, there is clearly a unique imagination at work.

At least, it was unique at the time. After Rousseau, as I discovered at that Tate exhibition, a whole school of naive art has developed, characterised by vivid, sometimes eccentric, colouration and “incorrect” perspective. A painting by the contemporary British artist Daphne Stephenson, Jungle Scenes, particularly caught my eye: this would make a good jigsaw too, though as far as I know none exists.

But Stephenson is just one among literally hundreds of artists in the naive style, though I would argue that their technical skills go far beyond what naive might imply. To see a wider range of their paintings, just put “naive art images” into Google and see what comes up. It’s like discovering that modern music is not all like Stockhausen and Berio, after all, but encompasses a much wider range of styles, some of which are far more pleasing to the ear without being in any way meretricious.

At Painshill I bought a couple of bottles of the local dark beer in readiness for John’s next visit. I also bought a large screw-top bottle of Kent cider for when I make beef stroganoff, and a locally made chicken and bacon pie, which I have since eaten; it was pretty good. There were gooseberries in punnets too. We used to grow gooseberries at Score Lane in Liverpool, where Mum and Dad were living when I was born, and I seem to remember that in my boyhood gooseberries were far more widely sold than they are today. Of course, that was before the advent of polytunnels, which have extended the English soft fruit season, especially for strawberries, by several weeks. Who will choose gooseberries when strawberries are available?

Actually, I might. My gooseberry pies are pretty nice, even if I say so myself, and they can be put aside in the freezer, ready for the winter when they will be more than welcome. But the gooseberries at Painshill were ridiculously expensive. £3 a punnet – no, thank you. I can wait for the pick-your-own berries at Leapers Rock Orchard near Carnforth, where I shall be next week.

——————–

A Sea Symphony

3 July 2017

When I first came to London I spent all my spare cash, and then a bit more besides, on cheap seats at concerts or the theatre, or occasionally at the opera or ballet. I improved my musical education immeasurably, and still have the concert programmes in a box upstairs in the loft to prove it.

But in recent years I have been a much less regular concert-goer. While I was still working, I came to realise that in concerts I often nodded off to sleep (and sometimes jerked awake when the music became especially loud, which was embarrassing). Since I retired, attending a concert up in London has meant a time-consuming return journey by train, with extra time spent hanging around when the connections at Clapham Junction are not convenient. And, besides, I have a good collection of CDs to satisfy my musical cravings.

So, when I went up to the Festival Hall last week for a concert, it was the first time in several months that I had done so. But this was a special occasion. The Bach Choir, accompanied by the Philharmonia Orchestra, were performing Vaughan Williams’ Sea Symphony, which is rarely programmed as it requires a large orchestra and choir with two soloists, takes a full hour and is not guaranteed to draw a large audience. Also on the programme were Elgar’s Cello Concerto and a short new work for unaccompanied choir by James MacMillan.

So, when I went up to the Festival Hall last week for a concert, it was the first time in several months that I had done so. But this was a special occasion. The Bach Choir, accompanied by the Philharmonia Orchestra, were performing Vaughan Williams’ Sea Symphony, which is rarely programmed as it requires a large orchestra and choir with two soloists, takes a full hour and is not guaranteed to draw a large audience. Also on the programme were Elgar’s Cello Concerto and a short new work for unaccompanied choir by James MacMillan.

Michelle and Andy came too. Michelle has become something of an opera buff, certainly more knowledgeable than I am, and can be persuaded to join me for concerts when there is plenty of singing. She is not usually so keen otherwise. Andy sometimes comes too, but I’ve never been quite sure whether he actually likes the music, wants to learn, or is just there for moral support.

In any event I don’t think either of them knew what they were letting themselves in for. I did, at least up to a point. One of my CDs is a recording of an old performance of the Sea Symphony, conducted by André Previn. But after last week’s performance I wondered whether I had ever listened to the music as closely as I had thought.

It was really good. Really, really good. I might quibble about details: the orchestral ensemble was not quite perfect; the baritone soloist Roderick Williams, whom I know to be an excellent singer, was a bit underpowered on this occasion. But the Bach Choir were on top form, and David Hill, who is their regular chorus master and on this occasion also conducted (sometimes they bring in guest conductors), gave the music both a sweep and a shape, which in a work of more than an hour is no easy thing. It held my attention from first to last and I was in no danger of nodding off.

The Sea Symphony is a setting of words by Walt Whitman, selected and arranged by the composer. It combines a vivid literal depiction of the sea, complete with calms and storms, endless horizons and surging power, with an extended metaphor of the soul as a ship at sea, passing through life and beyond. The opening movement begins with a fanfare, and as I listened to the music which follows (the movement is about 20 minutes long) I suddenly realised that this is the wellspring from which much modern film and television music is derived. Only Debussy’s La Mer, which was written at about the same time as the Sea Symphony, has been equally influential. La Mer is of course a recognised masterpiece, and Debussy’s calms and storms are as evocative as the Sea Symphony, but Vaughan Williams’ broad, flowing tunes for the ocean expanse, and his triplet lilt for the ship at sea, are entirely his own.

It isn’t unusual for film and television composers to borrow from the classical repertoire; indeed many 20th century composers wrote for both the screen and the concert hall. But I don’t think I had ever previously realised how central the Sea Symphony has been to those borrowings. Nor had I realised how far it may be regarded as the progenitor of a long tradition of symphonic writing in Britain. The Sea Symphony precedes even Elgar’s two symphonies (which in my opinion are much inferior works), though Elgar was Vaughan Williams’ senior by 15 years, and is a precursor to symphonies I have enjoyed by Arnold Bax, William Alwyn, Robert Simpson, Edmund Rubbra, and others.

The two central movements of the Sea Symphony are relatively short. The second movement is a slow nocturne, setting Whitman’s poem On the Beach at Night Alone, a calm contrast to the fortissimo climaxes of the first movement. The third is a scherzo in which the choir (no soloists here) are really put through their paces. This was a highlight in last week’s concert: no recorded performance, however fine, can match the excitement of a top class choir at full tilt in a challenging work.

But it was in the final movement that I thought David Hill really showed his mettle. This is the point at which the metaphor of the soul as a ship at sea, which has been in the far background up to this point, is made explicit. The movement lasts a full half hour, and in other hands it can feel rambling and episodic; but not on this occasion. I found it riveting from first to last, and if the structure is episodic, which would in a way fit the depiction of the soul’s journey, I can only say that I didn’t notice.

David Hill and the choir must have been very satisfied by how the audience received their performance. The symphony ends pianissimo with pizzicato chords on cellos alone (I think) and after the last note was played there was a profound silence for several seconds before the applause began. This is a true mark of appreciation whenever it happens. The Festival Hall was by no means full, but the audience was attentive, and pleased.

I should also say something about the Cello Concerto. This is Elgar’s late masterpiece, written after the Great War in which he had lost family and friends, and the music is suffused with melancholy, and occasionally passion, which reflect the composer’s feelings. It was one of Mum’s favourite pieces, and she would have enjoyed the fact that the soloist Ralph Wallfisch didn’t engage in any histrionics. Mum disapproved of the way that some violin and cello soloists grimace and sway while they are playing, as if this adds passion and commitment to their playing. (She was right: it doesn’t.) We once saw Jacqueline Du Pré, the finest ever interpreter of Elgar’s Cello Concerto, in performance and Mum was dismayed by how much she swayed around, tossed her hair and generally emoted.

As for Wallfisch, I’m afraid this was rather a passionless performance. It’s impossible to play the Elgar without some feeling creeping through, but I think he left a lot unexpressed. Feeling should be conveyed in the dynmics, and in the rubato (that is, the subtle variation in tempo) which underpins the musical phrasing. In a concerto it is usually the soloist, rather than the conductor, who leads these things, and Wallfisch seemd to me to be too four-square for the music.

While Wallfisch was notably self-contained, the same could not be said of David Hill. Michelle and I were much amused by the energy he put into leading his choir and orchestra. Except in the quietest moments he was constantly on the move; by the end of the concert he must have been exhausted. I did notice however that he kept a firm beat throughout, and his energy was all expended in encouraging and directing his singers and players: none of it seemed gratuitous. I haven’t always been convinced by David Hill’s conducting at previous concerts, but on this occasion he was on top form, especially in the Vaughan Williams: I really do not think that any other conductor, however eminent, could have done it better.