Days with David and John

24 August 2017

After our visit to the Kew museums (see previous blog) we have had three more days together.

On Sunday we drove out to Rye, in the eastern corner of East Sussex. (Actually John did most of the driving, while I read the map.) This was David’s suggestion as he could not remember ever visiting the town, but John and I were quite happy to go along with it. It was a long drive, about 90 minutes from Oxted, but apart from one nasty queue the traffic was fairly quiet.

Rye is a bit of a backwater. It is not on any major routes, and cannot be reached by rail directly from London, so has little commuting. Until medieval times the town was a port, associated with the Cinque Ports, though not one of the original five. There is a strong connection with smuggling: Russell Thorndike’s Doctor Syn books, in which the smugglers are the protagonists and the enemies are the Revenue men, are set in the area. I remember reading Doctor Syn many years ago, but have no memories of the stories beyond the names of hero and author. Several films were made from them, but the last was in 1963, with Patrick McGoohan and George Cole – truly names from the past; the swashbuckler genre and its classic authors seem to be in eclipse.

In fact Rye has a range of literary associations. The most notable of its residents was undoubtedly Henry James, but others include E F Benson, Radclyffe Hall and (as a child) Joan Aiken, and the painters Edward Burra and Paul Nash. The children’s author Malcolm Saville, whom John, David and I all remember but is another now in eclipse, also lived in Rye for a time. Some of his books are on sale in the tourist information centre, though I cannot imagine that they would satisfy today’s pre-teens.

The town retains a good deal of charm, mainly in its largely unspoiled architecture, and seems able to assimilate the tourists whom it attracts. It has probably been protected by being slightly off the beaten path. The sea has retreated but is still only a mile or so away. We drove down to Winchelsea Beach, but there was a slight haze and we could not see across the Channel to France. I believe that in favourable conditions it is (just) possible to do so.

On Monday we went to the Weald and Downland Living Museum at Singleton, north of Chichester in West Sussex. This was an easier drive, though Horsham does seem (along with Kidderminster and Basingstoke) to have cornered the market in roundabouts. I had been to the museum before, many years ago with Mum and Dad, when it was still called the Weald and Downland Open Air Museum – accurate, but perhaps discouraging for visitors.

The museum is now one of the top tourist and educational attractions in the South East, and it is easy to see why. On the site have been collected and rebuilt a large number of old houses and other buildings, dating from the twelfth to the early twentieth centuries, from across the region. Some have been rebuilt brick by brick, some are reconstructions from available evidence, and some are a bit of each; the museum does not claim exact authenticity in every case, but is careful to show the basis for its reconstructions, and I think all the buildings contain at least some original elements.

The museum is now one of the top tourist and educational attractions in the South East, and it is easy to see why. On the site have been collected and rebuilt a large number of old houses and other buildings, dating from the twelfth to the early twentieth centuries, from across the region. Some have been rebuilt brick by brick, some are reconstructions from available evidence, and some are a bit of each; the museum does not claim exact authenticity in every case, but is careful to show the basis for its reconstructions, and I think all the buildings contain at least some original elements.

Nearly all the buildings are open for visitors to walk through. They are well documented with displays on weatherproof panels outside and a folder with more detailed information inside. Knowledgeable volunteers in some of the buildings will also provide further information. Half a dozen have kitchen gardens with plants typical of their periods, and there are also farm animals including shire horses. From my first visit I remember that they used to keep rare breed pigs too, but those seem to have gone, rather to my disappointment. Perhaps the smell was too bad.

We all enjoyed this visit and came away with a strong feeling of how lucky we are to live today with all our modern amenities and comforts. (Though I dare say that in the 23rd century they may make the same patronising remarks about us.) We had only two regrets: that, this being a Monday, the traditional craftspeople who display their skills at the Museum were not present, and that the weather was a bit damp and gloomy. One other observation of my own is that the buildings are only roughly grouped by type, and that there is no chronological thread running through the display, which makes it a bit harder to follow the gradual progress in domestic design and utilities over the centuries. I would also have liked to set my own pace so I could read the detailed information in all the folders. Of course in that case I might still be there, two days later.

After leaving the Museum we drove on southwards to Selsey Bill, which is a headland jutting out into the English Channel south of Chichester. None of us had ever been here, but I was curious to see it, as it is mentioned several times in Patrick O’Brian’s books (see blog on 26 April). In fact it is an unremarkable place, very low-lying; there is an RSPB seabird sanctuary which on some other occasion we might visit. But the town of Selsey has a faded, faintly desperate air, as though it had been left behind. Perhaps places like this will receive a new lease of life if/when we leave the EU and people can no longer afford to take their holidays abroad. It’s a sobering thought.

Yesterday we drove out to Tenterden, back in the direction of Rye but not quite so far. This was David’s suggestion; he had conceived a desire to visit the Chapel Down winery, which is located there. The winery offers guided tours, followed by a wine tasting. I booked us in for this, and for lunch afterwards at the winery’s restaurant, the Swan.

The tour was quite informative. I now have a better idea of the winemaker’s calendar and of why and how English winemaking is prospering, of how the production of white wine differs from red, of the three ways that rosé wine is produced, and of how red wine gets its colour. I have also had a brief tutorial in the art of wine tasting, and may be better equipped in future to tell the difference between a Sauvignon and a Chardonnay. What John, who rarely drinks wine, made of all this I’m not sure. Afterwards we were let loose in the winery shop. I bought a couple of bottles for Michelle as a guilt offering for forgetting her birthday, and John and I together bought David a pair of elegant Dartington wine glasses as a keepsake present for his 60th birthday, which will fall just after he returns to Australia.

But the main glory of this visit was the lunch, which really was quite exceptionally good: in the same style as at the theatre restaurant in Stratford, emphasising quality above quantity, but two or three notches higher class than that (and Stratford is pretty good). My only regret was that the wine-tasting beforehand had removed my appetite for a glass of wine to go with the meal. Wine-tasting is all very well, but perhaps best not performed on an empty stomach.

After lunch we went back into Tenterden to visit the terminus of the Kent and East Sussex Railway, a heritage line which snakes for ten miles across the empty Sussex lowlands. There were two engines in steam, and we saw them both: an ex-GWR pannier tank and a Terrier tank engine, small and lightweight but surprisingly powerful, which David and John were particularly pleased to see. No doubt they will write more about the engines in their blogs in due course, much more knowledgeably than I can do.

We were a bit too late to ride on any of the trains, and anyway we all agreed it is much more interesting to stand and watch them running. While you are on the train, the one thing you don’t see is the engine. For photographs I recommend you look at John’s or David’s blogs.

And thanks to John for all the photos he has supplied for this and the previous blog.

——————–

Two Kew museums

24 August 2017

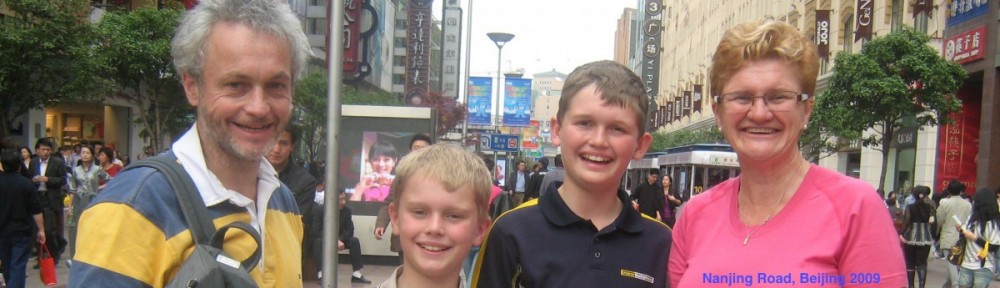

Over the last week I have been entertaining both my brothers, David and John, for a few days here in Oxted. John is here fairly regularly, as he lives in Manchester and comes down three or four times a year so we can go together to the theatre and to exhibitions. David only comes over from Australia once or at most twice a year, and we see him as often in Cark or Manchester, or in some foreign capital where he is attending a conference, as in Oxted. So this has been a rare opportunity.

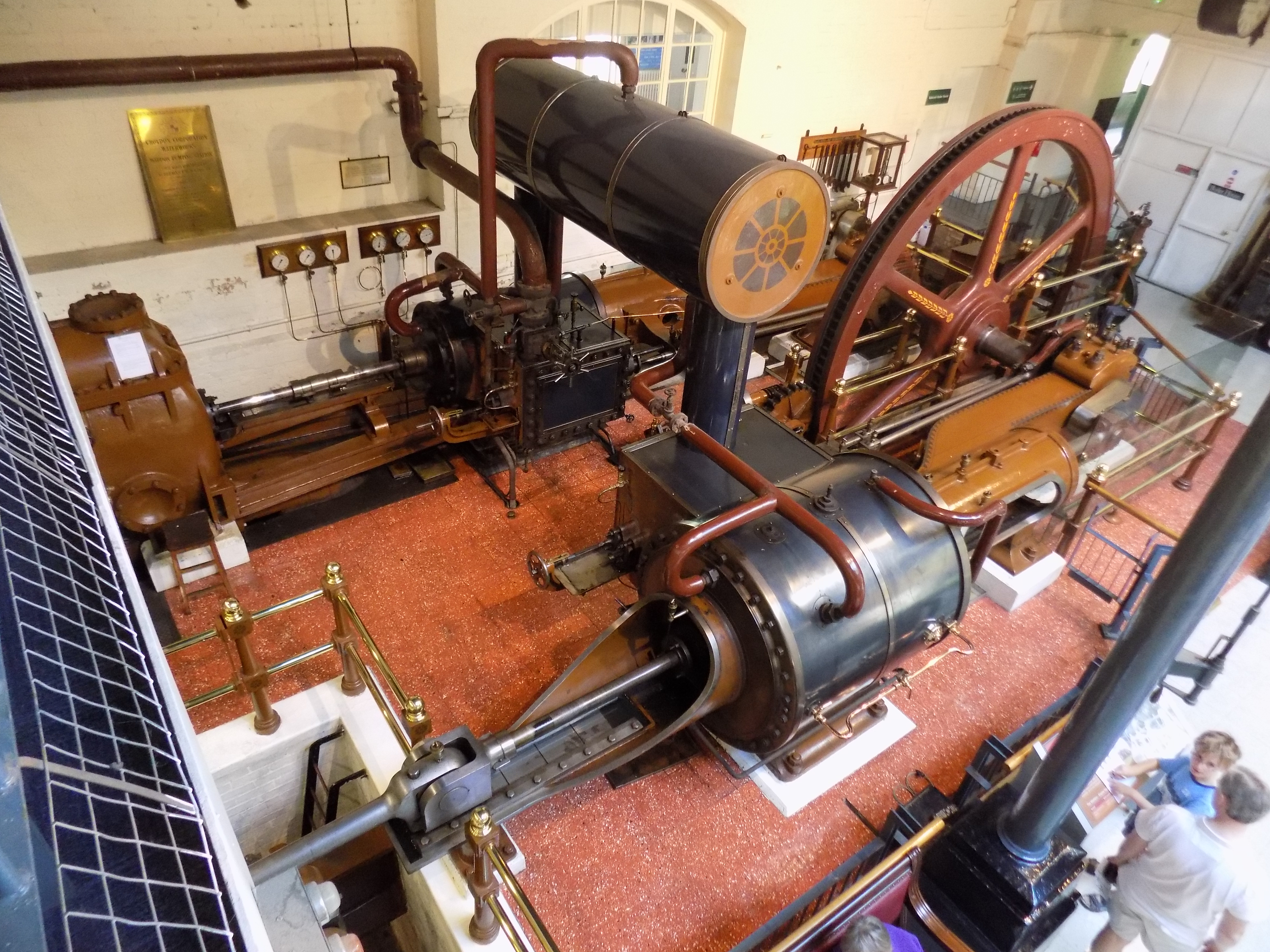

We have had four full days together. The first day was Saturday, and we went up into London to visit two slightly out-of-the-way museums, both recommended by my friend Trevor. The first was the London Museum of Water and Steam, which is housed in an old water treatment plant near Kew Bridge. Its main claim to attention is that it is home to a small collection of working steam pumping engines. (“Working” for this purpose means that the pumps can be fired up and operated; they don’t actually pump anything these days.)

The “Waddon” pumping engine, last of the engines on display at the museum still to be in service. It was decommissioned in 1983. We saw this one in operation; the power is almost palpable

This was a great success, even though only a couple of the pumps were in operation. I suspect that if all were put to work at once the building would shake apart. There is something about steam-powered machinery (not just railway engines, though those are what fascinate David and John the most, as you can read elsewhere in these blogs) that is curiously stirring. Perhaps it is just that the energy being put to use is so visible and, indeed, audible.

But even the pumps not in operation are impressive. We climbed two steep flights of stairs to have a top-down view of the two largest machines: the 90-inch engine, built in 1846, which is still in working order and the 100-inch, which isn’t. You have probably seen pictures of pumps like these. Both are beam engines, with a massive horizontal beam at the top, rather like a colossal pair of scales.

I imagine that the beams must have been cast in situ, but even so I can scarcely imagine how they were hoist into place. Notwithstanding its massive solidity, soon after first being brought into use in 1871 the 100-inch actually cracked during operation – the noise must have been like a thunderclap – but amazingly it was fixed and put back to work. You can still see the join.

I was equally interested by the static displays which tell the history of London’s water supply right up to the present. I had not realised the significance of the giant ring main completed in the early 1990s which helps to secure a continuing supply across the city, nor had I known that some of London’s water is now obtained by desalination at a new plant near Beckton. The water is taken on the ebb tide, when it is a little less salty.

There were also displays to show how water is recycled and purified. I had always wondered what is going on in those circular gravelly pits you can see in sewage works; now I know. But I think the exhibit we all liked best (apart from the engines) was the video of a robot rat running through a sewer line and encountering a real rat along the way. The robot rat is a small automated vehicle, fitted with lights and camera, that is controlled remotely by engineers: it enables small pipework to be inspected and is able even to perform minor repairs.

Some of the other exhibits were curiously – even alarmingly – familiar. The museum has a display showing the development of sanitary ware and technology. One of the pieces on display is a Bendix washer-dryer just like the one which was Mum’s pride and joy.

I remember the machine well. It was set up in the outside porch, and when first put to use it vibrated so strongly that it walked across to the far wall. This was also the machine in which Mum shrank my beautiful woollen cricket pullover to the size of a doll’s: but it was so funny, and she was so mortified, that I forgave her, and the incident has become part of family lore. We were all, however, slightly unnerved to realise that what was state-of-the-art technology in our youth – for we all remembered the Bendix – is now fit to be displayed in a museum. Such are the workings of anno domini.

Just down the road is the Musical Museum, which houses one of the world’s foremost collections of self-playing musical instruments. (Does that sound nonsensical? Think of musical boxes and piano rolls.) We went there after lunch and arrived just in time for the guided tour, which was just as well. You can wander around the museum on your own, but only the guide knows how to make the instruments play. We saw everything from early musical boxes, including a tiny instrument barely larger than a matchbox, to the Wurlitzer cinema organ which they have on the top floor and is in full working order.

It is easy to laugh at old technology, but really, some of the noises made by these strange instruments had to be heard to be believed. In the days when they were being developed, recorded music was unheard of or in its infancy, yet it is hard to imagine that anyone got any real pleasure from listening to their music, beyond their initial amazement at the misplaced ingenuity that had been devoted to their construction. Only the player piano, reproducing a performance by Rachmaninov which had been recorded on a piano roll (made of waxed paper), emitted anything like a pleasant sound; and even in that case, I think the choice of music, a short piece full of strong accents and with little delicacy, was made to show the instrument in the best possible light.

Of course the manufacturers were limited in the range of sounds they could reproduce. A piano is relatively easy to operate mechanically, though none of the machinery to mimic the actions of a live pianist seemed to me to be capable of capturing the nuances of phrasing and expression that are required to make a piano sing. But, beyond that, the designers were limited mostly to percussion instruments, tuned (like xylophones) or untuned (like snare drums). Even allowing for changes in musical taste, the performances given by these machines were just bizarre. There was one machine designed to play two violins – you could see them – but the sound it obtained was almost unrecognisable.

The Wurlitzer was slightly different. For one thing it consists in part of a pipe organ, recognisable from churches and concert halls the world over, capable of producing a wide range of genuinely musical sounds from its array of pipes, including fair imitations of orchestral wind and string instruments. What distinguishes the Wurlitzer is that it also incorporates the tuned and untuned percussion from the earlier generation of mechanical instruments, plus some sounds peculiar to itself – sirens, whistles and so on. It is from the Wurlitzer that we get our modern-day expression “with all the bells and whistles.”

The Wurlitzer can be played by a performer sitting at the keyboard, and I dare say that a concert given by a capable musician would be worth hearing. But it can also be played automatically from a waxed paper roll, and in this way we were treated to a performance of Chopin’s famous Nocturne in E flat. Truly, I have never heard such a travesty. I don’t think the recorded performance was all that great to begin with; Chopin requires a certain amount of rubato (minor variations of tempo for expressive purposes), but this was excessive, and almost random. On top of which the guide took it upon himself to change the stops on the Wurlitzer keyboard so as to demonstrate the machine’s capabilities. Chopin would have turned in his grave. It was horrible.

I had thought that David and John would be more interested by the steam engines, less by the musical instruments, but in fact they seem to have enjoyed both. These museums deserve to be better known; if it had not been for Trevor, I would never have been aware of their existence. Anyway, we all had a good day out.

——————–

Changing a lightbulb

18 August 2017

A couple of years ago the fluorescent light tube in my garage burned out. I took it down to the electrical goods shop to obtain a like-for-like replacement, but when I brought the new one home and fitted it into place it didn’t work. No, actually that is not quite true. If I left it switched on for a minute or two it would flicker slightly. On a couple of occasions I accidentally left it switched on overnight and in the morning noticed that the light was now working perfectly. But, if I switched it off and then back on again, the problem recurred.

Oh, well. Something wrong with the fitting. But I scarcely use the garage anyway. It houses my car, my two toolboxes (which I rarely want), my gardening kit (ditto), and other bits and pieces which I may possibly want at some time in the future and am therefore disinclined to throw away. Of late I have also used it for the specially selected bottles of beer which I keep in store for my brothers when they come to stay. And the gas and electricity meters are in there too.

So when the meter reader comes round, he needs his torch. And if I want to take the car out I have to feel my way past, in the near-darkness, to get to the garage door, which only opens from the inside. The keyhole on the outside of the door was painted over before I bought the house, and anyway I don’t have a key. And it’s a useful security measure.

At least, this was the state of affairs until yesterday. Then my brother David took a hand. He arrived from Australia two days ago, and in search of beer discovered that the garage light didn’t work. I had to explain that it had been like that for quite a while and that it was not a massive inconvenience. But when he volunteered to put it right I was of course grateful. I think he has the idea (not altogether incorrect) that I am not terribly handy about the house, in fact a bit helpless when it comes to minor maintenance. A few years ago he ensured that my coat hooks, which John had managed to pull off the wall, were safely fixed back in place with extra-large strong Rawlplugs to secure the fitting. I wouldn’t even have known such things existed.

David’s first thought about my garage light was that the starter might not be functioning. (Fluorescent tubes need a starter, though not always, for reasons you can read about online.) Sometimes the starter is a visible fitting at the end of the tube, but that was not the case here: evidently the starter was contained within the fitting itself. So I made sure the switch was turned off; then David took out the non-functioning tube and removed the fitting cover. Unfortunately the label inside did not explain which piece was which, and we had to guess which of the various small boxes inside the fitting was the starter.

At this point I said (quite truthfully) that I didn’t particularly want a replacement fluorescent light. If it had been a simple repair, fine; but otherwise I would rather have a different type of light fitting.

The next step was to take down the fitting altogether. We found a suitable screwdriver in my best toolbox and David, with some slight difficulty, detached the fitting from the ceiling and pulled it loose. There was a sudden bang and a flash. Switching the light off had not stopped the current. David didn’t seem surprised and said something about a ring main which I didn’t understand, but I was horrified. Here were four wires hanging down a couple of inches from the ceiling and at least one must have been live. However, the circuit breaker (also in the garage) had tripped, and before we switched the power back on David made sure that the offending loose wires were made safe.

We decided to go to the shops to see if we could find something suitable. We walked into the village only to find that the local hardware shop, Morton the Padlock, has just ceased business – they were actually clearing out the store when we got there.

So we needed to visit the nearest hardware superstore where we could look up and down the shelves for something suitable. As far as I knew the nearest was Homebase in East Grinstead, so we set off in my car. At the roundabout near Godstone there was a sign warning that the East Grinstead road was closed at South Godstone for repair work and directing us along an alternative route. Almost immediately after the roundabout we found a traffic jam, presumably caused by the diversion. Neither of us had any patience for this, so we turned around and came home.

David used his smartphone to check whether there were any other stores within a reasonable distance in other directions, but drew a blank. Meanwhile it had occurred to me that by following minor roads we might be able to bypass both the road works and the diversion. I found my local map and, lo and behold, there is a perfectly good alternative route, passing through Tandridge village an avoiding South Godstone. We gave that a try, and knew we were on the right track when we found at various places along the way improvised warning notices stating that the road was not suitable for HGVs, though if I had been an HGV driver I am not sure I would have paid much attention: the notices looked unofficial to me, and I might have written them off as selfish residents not wanting their sleepy Surrey lanes disturbed by heavy traffic

Anyway, we eventually got to East Grinstead and found in Homebase a nice, bright, circular light, intended for use on bathroom walls but perfectly well adapted for my garage ceiling. It is an integral LED unit, meaning that when the LEDs fail, as they will do eventually, it will have to be replaced. But as that is what I, or rather David, have already had to do this time, it did not seem such a drawback. Besides, it seems likely that the unit actually contains several separate LEDs and they are unlikely all to fail at once. And it has a design life of 30,000 hours, which means it could still be going when I am no longer living here.

We took our trophy home and David fitted it in the garage ceiling for me without electrocuting himself. While standing on the stepladder David had me hand up, and then take back, the two small screwdrivers (one a Philips) he was using. But when we tidied up afterwards, neither of us had any idea what had happened to the one with the red handle. It wasn’t in either of the toolboxes, or on any of the shelves, or on the floor, or in one of our pockets. Nor was it in the kitchen or the downstairs bathroom which were the only other places we had been. Any member of my family will tell you that I am in the terrible habit of putting objects down in the wrong place and forgetting where they are, but a quick search usually turns them up. This one is still a mystery.

I am very grateful for David’s efforts. But changing a lightbulb is clearly more complicated than people say.

——————–

More Old Trafford memories

15 August 2017

My previous blog has put me in mind of other times I watched cricket at Old Trafford. I mentioned the Roses match in 1964 and the Prodger match in 1965, but at around that time Dad and I also saw Lancashire playing Glamorgan. Despite a search of my old Wisdens I cannot work out whether it was in ’63, ’64 or ’65. I know that Ossie Wheatley and Jeff Jones opened the bowling for Glamorgan, but that could have been any of those years.

It was the first time I had heard Dad’s trenchant criticism of bowlers he thought over-rated: Wheatley, he said, was too old, too fat and too slow. He did, however, have a high opinion of Jones, father of Simon Jones who played in the famous 2005 Ashes series. He liked his pace and his classical left-hander’s bowling action, and in fact Jeff went on to play for England, though his career, like his son’s, was curtailed by injury.

As time passed I was trusted to make my own way, by train, to Old Trafford; easy enough, as there was a railway station (now a stop on the Metrolink tram) right outside the ground. One of the first games I went to see was against the touring New Zealanders in 1969. Dick Motz, a fast-medium bowler and lower order batsman, hit over 70 for the tourists, including four straight sixes in the direction of D stand (see previous blog). Six-hitting was much rarer then than it has now become; bats had regular dimensions, not the thick springy planks that top-class cricketers now use, and to clear the boundary required a very clean strike of the ball.

On another occasion my boyhood friend Paul Power (who sadly died in his early twenties) and I went to Old Trafford to watch a pre-season friendly between Lancashire and the then Minor Counties champions, Cheshire, only to discover on arrival that the game had been cancelled because the ground was too wet. No internet in those days. Still, I expect I enjoyed the train journey.

One more successful trip was in 1970 to see another Roses match, this one in the now defunct 40-over Sunday league. Lancashire had won the inaugural competition the previous year and would repeat the triumph if they defeated Yorkshire, which they comfortably did. I have no memory of the play, but I do recall that we sat on the grass behind the boundary rope, which for safety reasons is no longer permitted. On that occasion Old Trafford was packed with a crowd of more than 30,000, supposedly the largest since the war. Unfortunately I have been unable to find any photographs. The first years of the 40-over competition were every bit as popular as Twenty20 is today, and for much the same reasons: finished in a day, definite result, more exciting batting. But over time interest dwindled, which is one of the reasons I fear that in promoting T20 today the cricket authorities may be stuffing too many of their eggs in one rather fragile basket.

Crowd control may be greater now, but what has also changed is the noise. During the 1964 and 1966 Test matches, the crowd was expected to be silent before each ball was delivered. On more than one occasion the batsman refused to take his stance until there was a hush. There was not much barracking, though slow handclapping did break out from time to time if play became unendurably turgid. It’s unimaginable that modern crowds would exercise such self-restraint. Silence is still supposedly the rule at tennis and golf, where the spectators are much closer to the play. But trying to quieten a modern crowd at cricket would be utterly futile, and on the whole I think it is a change for the better.

In the 1960s pitches were still being left uncovered and players disinclined to continue in the slightest rain, so it was quite common to lose playing time. (This was offset by the difficulty of batting on a drying wicket, which led to generally lower scoring and quicker finishes.) As it happens, both the 1964 and 1966 Tests were unaffected by the weather. But modern crowds are inclined to get fractious unless play is plainly impossible, and among Old Trafford’s innovations over the last few years have been far improved drainage and the installation of floodlights. Supposedly play is supposed to cease if the floodlights have “taken over” from natural light, as opposed to simply enhancing it, which is quite a hard distinction to understand, let alone judge. However, it is a good innovation. A good deal of the India Test in 2014 was played with the assistance of floodlights, and so far as I could see the players were not in the least bothered by them, but they were of little help with the torrential downpour on the second afternoon, the worst I have ever experienced at any cricket match anywhere. Even the new improved drainage could not cope.

Crowds often find other ways to amuse themselves. It has become almost traditional for groups to wear fancy dress: this year we noticed a line of red pillar boxes and a row of bananas. This is a great joke to begin with, and quite harmless to others, but I suspect by the end of the day the costumes get rather hot, not to mention smelly. It would never have happened in the ‘60s. Thanks to John for the picture.

Crowds often find other ways to amuse themselves. It has become almost traditional for groups to wear fancy dress: this year we noticed a line of red pillar boxes and a row of bananas. This is a great joke to begin with, and quite harmless to others, but I suspect by the end of the day the costumes get rather hot, not to mention smelly. It would never have happened in the ‘60s. Thanks to John for the picture.

However, some of the crowd’s amusements are more annoying than funny. Thankfully the fashion for Mexican waves seems to have passed, but at least they did express to the players that they were failing to hold the crowd’s attention.

The latest craze, one that has been going for a few years now, is the creation of “beer snakes” by stacking empty plastic beer glasses in long rows, which can stretch for a considerable distance. The problem with this is that it is extremely distracting for other spectators in the same stand who actually want to watch the cricket, and it’s unpleasant to have old beer dripped on your head. John and I endured a particularly bad episode in a Test match a few years ago, since when we have sought the relative safety of the alcohol-free and family stands which have been a recent innovation at Old Trafford. I suspect that we were not the only spectators to complain that their enjoyment of the game had been ruined by the crowd’s wilder antics.

This year, in the family stand I’m sorry to say that after lunch someone produced an inflatable beach ball which was repeatedly punted across the spectators’ heads, much to the enjoyment of the children (but not only the children) in the crowd. This was every bit as distracting as beer snakes, though less disgusting, and I thought it rather selfish. Perhaps I am becoming an old fogey, but if so then John is a young one, as he was at least as annoyed and distracted as I was.

These days I only go to Old Trafford for the Test matches. (Since one-day cricket started to be played in coloured clothing, with a white ball, I have lost interest.) Living in Oxted, my home team is Surrey, who play at the Oval in south London. But I have always found the Oval a rather unwelcoming place, though I believe that, like Old Trafford, it has received some overdue investment in the last few years; perhaps I should try again some time. Surrey are the bloated plutocrats of county cricket and much disliked by the supporters of other teams; on the Guardian cricket blogs they are known by the cognoscenti as “Slurrey,” which is a fair reflection of general disdain.

Of the London-based teams I far prefer Middlesex, who are cricket’s impecunious aristocrats. (You can play this game for quite a while: thus Hampshire are the nouveau riche, Yorkshire the grumpy old men, and so on.) And Lord’s, where they play, is a far nicer ground. But it is rather a long trek for me across London.

So if I want to watch a county game I am most likely to go to Hove, which is a reasonably straightforward train journey and a beautiful compact ground. It is an even easier drive, but parking in Hove is a nightmare. Sussex had a period of success a few years ago and put their prize money into ground improvements, so Hove is now not just welcoming but well-appointed. However, the team is going through a lean patch at the moment, in the lower division of the championship, so they are not playing against Lancashire this year and I haven’t been to see them.

——————–

Old Trafford (the cricket ground)

13 August 2017

John suggested I write this blog after we attended the first two days of the England vs South Africa Test match a week ago. Since then, I have been trying to remember when I first went to a game at Old Trafford. Dad certainly took me to the Roses match in May 1964. It was probably a birthday treat. I do not remember all that much about the day, but I do know it was the first time I saw Geoff Boycott bat. Dad had obviously been reading about him in the newspaper, and pointed him out to me as a future England player. He duly made his debut in the first Test of that summer.

In those days Boycott’s fielding was atrocious (though the general standard was also far poorer than it is today). But what set him apart was his batting, and most particularly his willingness to run sharp singles. I remember how, with his partner Ken Taylor, he ran the Lancashire fielders ragged that afternoon. I wasn’t terribly knowledgeable at the time, and Dad had to point out to me what was going on, but you can see it has stuck in my mind.

That same summer we sat through all five days of the infamous Test match in which Australia scored 656 for 8 declared (their captain, Bobby Simpson, making 311) and England replied with 611 all out (Barrington 256). There was just time for two overs of Australia’s innings and the match was a draw. Not quite pointless: Australia needed only a draw to retain the Ashes, and Simpson quite cold-bloodedly set out to ensure that they did so. But it was a dreadful advertisement for cricket, which was a bit in the doldrums in the 1960s anyway. Dad swore he would never go to see the Australians again, and I believe he never did.

We also went to the West Indies Test match in 1966, a much more entertaining occasion, though England lost by an innings inside three days. It was the only time I saw the great Wes Hall, and my first sight also of Rohan Kanhai, Gary Sobers and Lance Gibbs. That was a great West Indian team and, unlike those of the 1970s and 1980s, did not rely on its pace battery for its success. In fact Gibbs, a truly great off-spinner, played a major role in bowling England out twice within a day and a half.

But I think John really wanted me to write about my memories of the ground itself. Now, bear in mind that in 1966 I was just thirteen years old. But I have a strong impression that visiting Old Trafford in those days was a bit like travelling back to the 1940s or even the 1930s, when crowds turned up to cricket in their thousands and demanded little in the way of facilities. The gents’ lavatories were primitive (to be fair, this seems not to have been uncommon at sports grounds in the 1960s), and the catering was like the worse kind of transport café. For the Tests, hard cushions could be rented to soften the bare wooden bench seats, in case you had a tender behind, or perhaps to forestall one; but for other matches you had to look after your own comforts.

This photo, which I found on the internet after some searching, shows the old D stand just to the left of the white-painted seats which served as a sightscreen. The red building at back right is the old Press box.

It wasn’t all bad. Dad had a strong preference for sitting in D stand, a position almost directly behind the bowler’s arm at the Trafford (eastern) end of the ground. This is by far the best position from which to watch, as you can follow the flight of the ball from the moment of delivery, and can also see whether it swings or spins. The television companies invariably set up their cameras in this position, so it is familiar even to casual viewers. From sideways on it is harder to follow the ball’s flight and you have to infer what the ball is doing from how the batsman plays. D stand was also built with a slightly steeper rake than the stands to either side, giving a better view.

But in D stand you were totally exposed to the elements.: there was no shelter if it rained, though in those days it didn’t take much for the players to return to the haven of the pavilion, so the spectators could at least go and huddle in the limited shelter behind the stands. One year we tried the stand at the opposite end of the ground, with a similar view from behind the bowler and a little more shelter. But the rake of the seating was lower, and the view inferior. I remember in that game a batsman called Prodger, playing for Kent, made a deadly dull 57. Never did a cricketer have a more apposite name; he was clearly born to prodge.

The contrast between then and now is like chalk and cheese. For the purist, the most obvious change is that the playing square has been rotated through ninety degrees, so that where D stand used to be now gives a sideways view of the action; the pavilion, which used to be sideways on, now also has the best view, behind the bowler’s arm. This was done as batsmen in September had started to complain of the low sun in their line of vision, which had not been an issue when the season ended earlier. Amazingly the change of orientation does not seem to have affected the quality of the pitches, which are still truer, faster and potentially more helpful to spin than any other Test ground in England.

For a casual visitor it is the surroundings which have most changed. In the early 2000s Lancashire were told that to keep Old Trafford’s Test match status its facilities needed to be greatly improved. An ambitious redevelopment plan was drawn up and – in the face of some stiff legal opposition from other local developers and landowners – is now on the point of completion. Around the ground are three large new structures: one either side of the pavilion, and one on the other side of the ground. They are, respectively, a conference centre, a hotel and a media centre in which the players’ changing rooms are also located.

Old Trafford on 1 August 2017. An electronic sightscreen, currently showing an advertisement, has been placed in front of the pavilion.

The pavilion itself has also been extended upwards and sideways. When John and I went to the Test match in 2013 only the conference centre had been built, and it looked oversized and hideously out of place. But now the scheme is complete, and it looks fine: not beautiful, but not ugly or ill-proportioned. And the hotel and conference centre should secure Lancashire cricket’s financial future for years to come.

The old scoreboards have also gone, to be replaced by two new large video screens, which at the whims of their operators show the score, replays of the live action (including when the Decision Review System is invoked), or advertisements which I suspect pay for the whole thing. The video replays are fun, but it is a bit of a shame that there is not a permanent display of the score; if the operators decide to show something else, you have to wait for this essential information. And, like the old scoreboards which surprisingly often did not agree, the screens sometimes show different things – which is great if, but only if, you are in a good position to see them both.

Our casual visitor would also notice that the seating has greatly improved. The wooden benches with stencilled seat numbers have been replaced by individual bucket seats, made of hard plastic, a bit cramped (no more so than before) but far more comfortable. The cushions have gone; I think they may have been sold to the Globe theatre in London (see my blog on 23 June). The Gents are now relatively well-appointed and clean, though there are queues, which never used to be the case; and there are proper facilities for ladies, which – to judge by the crowds at last week’s Test – has paid off in terms of attendances. The catering is more varied, though prices are still extortionate, and there is a cricket shop for browsing in the lunch interval, or if it rains. You might even buy something.

I do regret the loss of D stand; you now have to sit in the pavilion (which requires you to be a member of the county club) or be a media person to obtain as good a view. And I feel a nostalgic regret for the old scoreboards. But overall, despite the security queues which have become an unavoidable feature of modern life, Old Trafford is a far more welcoming place than it was fifty years ago. Let’s hope the Test and county game survives long enough to repay Lancashire’s investment.

Thanks to John for his two pictures of Old Trafford.

——————–

Two days at the Test match

6 August 2017

John and I spent yesterday and the day before at the Old Trafford Test match, fourth and final of a series in which England leads South Africa 2–1. These were a curious two days’ cricket in which both teams at different times seemed oddly reluctant to seize the initiative. On Friday it was mostly England; yesterday, possibly decisively, South Africa.

When Joe Root decided to bat first after winning the toss, he knew that the morning session would be largely a matter of survival. So credit to the three England batsmen who toughed it out. Cook, in particular, weathered two opening overs from Morkel which were as hostile as anything I’ve seen. Jennings was the only wicket to fall, and it was scarcely a surprise: his movement and technique are too stiff against high quality pace bowling. You are bound to wonder about the Division 1 attacks against which he has made plenty of runs for Durham during the last two years’ county championships.

But the South Africans contributed to their own lack of success by bowling too short. When the ball is moving off the seam, as it did on the green-tinged turf yesterday morning, the important thing is to pitch it up, so the batsman has no time to adjust. Even Morkel, consistently their best bowler throughout the innings, was guilty. As it was, the batsmen’s frequent playing and missing was safer than it appeared.

After lunch conditions were a little easier, and for nearly all the time South Africa rotated their seamers at one end while the left-arm spinner Maharaj bowled from the other. Maharaj is a good bowler, make no mistake. He is the kind of bowler England have desperately craved ever since Graeme Swann’s retirement, steady and wily in a support role, but also able to go on the attack when conditions favour him. Yesterday he was in containing mode, but it was disappointing that the England batsmen were so willing to accommodate him. Usually you can rely on Root to rotate the strike regularly and coax his partners to follow suit, but on this occasion he seemed content to wait for the very occasional bad ball and not seek to disrupt Maharaj’s rhythm. South Africa came into this match with only four front-line bowlers and England could have wrecked that strategy by milking Maharaj, but they didn’t seem to try.

The batsmen were complicit in all the first five England wickets to fall. Jennings and Westley both succumbed to indecision outside their off-stump, though it should be said in Westley’s defence that up to that point he had largely looked the part of an international No.3.

Cook seemed to play for spin that wasn’t there, an odd lapse from someone who is usually solid against spin, and Root was undermined by over-confidence, playing across the line on the front foot against the medium-fast Olivier, thus giving fresh ammunition to those critics who say he doesn’t convert 50s into 100s often enough for a top batsman. Malan’s downfall, caught off an over-ambitious drive, was horribly reminiscent of James Vince last year, who was dismissed several times in succession in that way. Do cricketers not learn from each other’s mistakes?

The one batsman to be genuinely got out was Stokes, who received a fierce yorker from Rabada that would have dismissed most batsmen. Only in this final spell did Rabada seem to work up serious pace; earlier in the day he had looked a bit out of sorts, perhaps because he was asked to bowl from the Brian Statham end – all the quicks in this match have preferred to bowl from the pavilion end (which Lancashire have rechristened the ”James Anderson” end – a worthy honour, or premature? One of the day’s less necessary debates.)

So Friday ended with England at 260 for 6 and South Africa slightly ahead in the match. But that changed decisively yesterday morning thanks to Jonny Bairstow and to some unwise decisions by South Africa’s captain, Faf du Plessis. The ball was only 9 overs old and du Plessis opted to begin with his two chief bowlers, Morkel and Rabada. Fair enough. Both bowled well, and for the first three overs England did not score a run. Then the batsmen got going. Roland-Jones and Moeen each perished after a couple of pretty shots, and Broad went almost immediately, but after 45 minutes England had put on nearly 50 priceless runs.

At this point du Plessis made a crucial error – in fact two, though one was understandable. He kept Morkel and Rabada bowling in the hope of cleaning up the last wicket quickly, but both were tiring and in retrospect he should have made the change sooner. Worse, he started setting ultra-defensive fields for Bairstow in the hope of forcing him to take singles early in the over and exposing Anderson to the bowling. It revealed a defensive mind-set which must have been discouraging for his team and especially his already tired bowlers. Bairstow farmed the bowling expertly, running twos to the boundary fielders, finding occasional gaps for fours, and trusting Anderson to take a couple of balls each over. Du Plessis had surrendered the initiative and never regained it.

Eventually he had to turn to Maharaj, who had a close lbw appeal against Anderson turned down in his first over and got Bairstow out lbw sweeping in his second. Bairstow had made 99 and the last wicket pair had put on 51, of which Anderson made 4. What made this worse was that on the previous evening Bairstow had clearly been less at ease against Maharaj than against any of the seamers. They say du Plessis is a good leader of his team, but I’d say that tactics are not his strong point.

When South Africa came out to bat, Anderson dismissed Elgar with the third ball, a classic (and plumb) lbw to a late inswinger. Then Amla came in and for a while made batting look easier than anyone else in the match. Suddenly South Africa were racing – and just as suddenly he was out, caught down the leg side off Roland-Jones for 30 that seemed to have taken no time at all.

At which point South Africa shut up shop. The next batsman in was Bavuma, who is technically sound but not one to dominate the bowling, and with him was Heino Kuhn, the opener who was plainly out of his depth but struggling on to save his Test career. Over the next 80 minutes they made just 37 runs before Moeen Ali put Kuhn out of his misery with the help of a sharply taken catch by Stokes at slip.

I won’t go through the whole of the South African innings: enough to say that it was a subdued affair until the ninth wicket partnership between Rabada and Morkel who, with nothing to lose, heaved some cheap runs at Moeen’s expense. Anderson bowled brilliantly, taking four wickets, and Moeen bowled a tidy long spell from the Statham end without ever looking threatening, but it was difficult to see the demons in the bowling which kept the batsmen so quiet. Even de Kock, who is not normally one to hang around, was unnaturally quiet, making just 24 off 66 balls.

England did not even need to be at their best. Bairstow missed two catches and a stumping; none of them easy, but a top-class wicket keeper would have expected to take at least one of them. Anderson missed with a throw, again not easy, when a direct hit would have run out Kuhn taking a sharp single, and Moeen, more culpably, failed to break the wickets first time after receiving a throw at the bowlers end to run out the same batsman. Even Stokes missed a couple of very sharp chances at slip off Moeen, though he made up for it with a stunning catch at gully off the last ball of the day to dismiss Rabada off Broad.

The pitch has clearly helped the bowlers, but not so far as to justify the strokelessness which at times affected both teams. Amla, and to a degree Root, Stokes and Cook, were all able to make steady progress despite the challenges – Amla a bit better than steady. It’s good to see a Test match pitch which gives the bowlers something, as too often in modern cricket their role seems to be purely cannon fodder. But it was a bit dispiriting to see two Test batting line-ups so little able to cope.