Coriolanus

28 September 2017

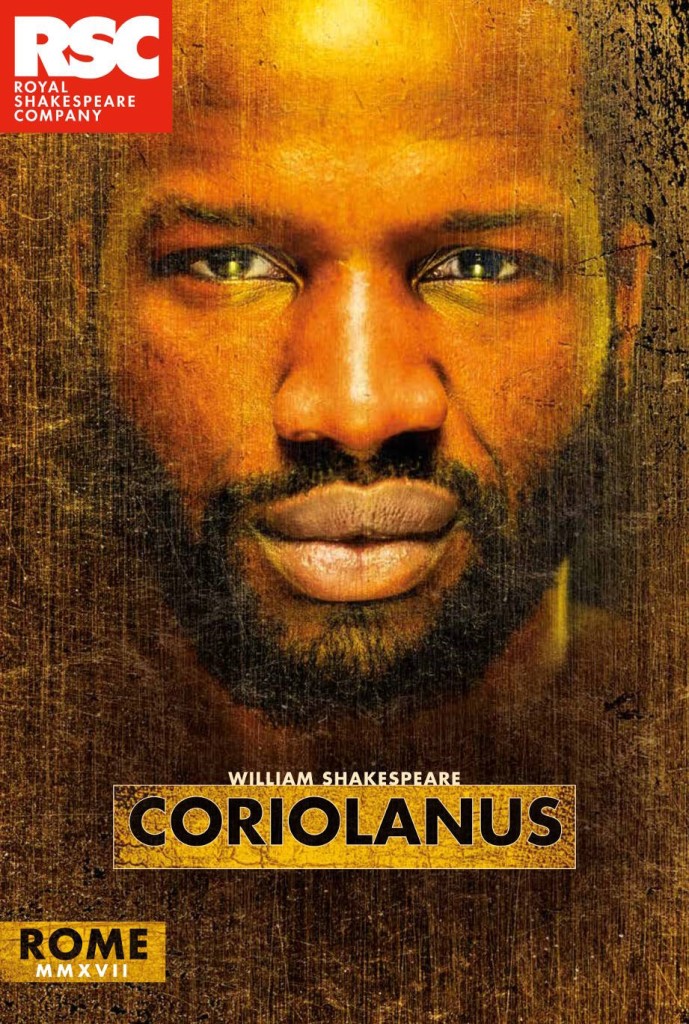

Last weekend John and I went, with my friends Chris and Janet, to see the RSC’s new production of Coriolanus in the main theatre at Stratford. The production is so new that we hadn’t seen any of the reviews in the papers – only the Times’ review had yet been published on its website, and as there is a paywall we weren’t able to read it. So for once we came to this show without any received opinions to interfere with our enjoyment.

Coriolanus is not exactly a rarity such as Henry VIII or Pericles, but it is not a regular staple of the repertoire either. It is one of Shakespeare’s longest plays; only Hamlet is longer, and while Hamlet is occasionally produced uncut (I believe the recent Almeida production, with Andrew Scott, is one such) I have never heard of such a thing with Coriolanus. Consequently the play may change, in large ways or small, from one production to the next.

Coriolanus is not exactly a rarity such as Henry VIII or Pericles, but it is not a regular staple of the repertoire either. It is one of Shakespeare’s longest plays; only Hamlet is longer, and while Hamlet is occasionally produced uncut (I believe the recent Almeida production, with Andrew Scott, is one such) I have never heard of such a thing with Coriolanus. Consequently the play may change, in large ways or small, from one production to the next.

The events of the play take place against a background of famine in Rome – a common theme throughout Roman history, so much so that it is arguable the Empire developed out of the need to secure the city’s grain supply. There had been famine in central England in the early 1600s and it seems likely that this was what initially drew Shakespeare’s attention to the story of Coriolanus as told by Plutarch. It is a late play, written not before 1605 but during the next two or three years.

I have seen the play at least twice before, but had not remembered how very political it is. My memory was that the tragedy of Coriolanus is essentially personal: the driven but prideful personality which makes him a great warrior also makes him unbending and incapable of compromise away from the battlefield. That was a true memory so far as it goes, but it is only part of the picture. This production brought out much more clearly the political confrontation between Coriolanus, representative of a privileged governing class, and the common people who demand respect to go with their bread.

What is interesting is how Shakespeare presents both sides of the argument. The plebeians, urged on by the tribunes who are their representatives, suspect the patricians of hoarding grain; and in this production a bizarre opening scene, involving a fork-lift truck, suggested that they might have a point. When Coriolanus wins a famous victory through an act of personal heroism the grievances are forgotten, but the tribunes connive to reopen the wound by carefully staged protests that exploit his pride and disdain, resulting in his banishment. However, without Coriolanus to lead Rome’s army, the city is defenceless when threatened. We are given a lesson in the expediency of compromise and the dangers of demagoguery (or the limits of democracy, depending on taste).

A couple of years ago John and I saw a very fine RSC production of Julius Caesar, directed by Gregory Doran, which I particularly remember for how well the crowd scenes were handled. It’s not easy to suggest an anxious, impatient, angry mob with fewer than 20 actors, but Doran managed it brilliantly. I think we saw some of the same stagecraft in this Coriolanus, the difference being that whereas in Caesar it is Mark Antony who arouses the crowd by his oratory, here it is the tribunes, and they do as much by behind-the-scenes plotting as by open demagoguery.

The two tribunes, who in history were always men, are in this production played by women: Jackie Morrison and Martina Laird. They were excellent. Their roles are less prominent later in the play, but for the first half they were arguably the stars of the show, operating like a pair of shop stewards manipulating the workers and exploiting the management’s prideful blindness. The RSC seems to have adopted a policy of offering male roles to women actors; we saw a good production of King John in 2012 in which the central role of the Bastard was played very effectively by Pippa Nixon. Both in that case and this, the effect has been illuminating, and so long as due thought continues to be given to meaning and context I hope they continue.

In the second half of the play, Coriolanus is exiled from Rome, joins his former enemy Aufidius (with whom we have earlier seen him fighting hand-to-hand), and eventually leads his army back to the very gates of Rome. The focus moves on to Coriolanus himself and his relationships, with his wife and son, with Aufidius, and above all with his mother. This change of focus makes the play feel fractured: the political themes of the first half are unresolved, while the personal themes of the second half have not been adequately prepared. The first time I saw the play, the role of Volumnia was taken by Janet Suzman, and throughout she seemed almost as important a figure as Coriolanus himself. I suspect that editing to bring out the politics has not been kind to the play’s overall structure.

Haydn Gwynne, who plays Volumnia in this production, is outstanding. The RSC clearly aims always to have its actors speak the verse so it is not only unstilted and meaningful, but has the rhythms and cadences of ordinary speech. Whether to convey passion, anger or grief, to persuade or denounce, it must be not just the words but the whole manner of speaking them that convinces. Suzman is a distant memory; I cannot imagine the role being played better than Gwynne does, and that is in part because she makes it seem so real.

I should put in a word, too, for Paul Jesson, an RSC stalwart, who plays Menenius, a subtle patrician who is ultimately overwhelmed by events, in a manner reminiscent of any number of Tory grandees out of the school of Macmillan. The type is instantly recognisable, and clearly meant to be recognised. Indeed it is clear that the whole production is intended to have contemporary resonances: no-one needs to mention Donald Trump or Brexit to feel that this is a play about bad, selfish, ignorant politics.

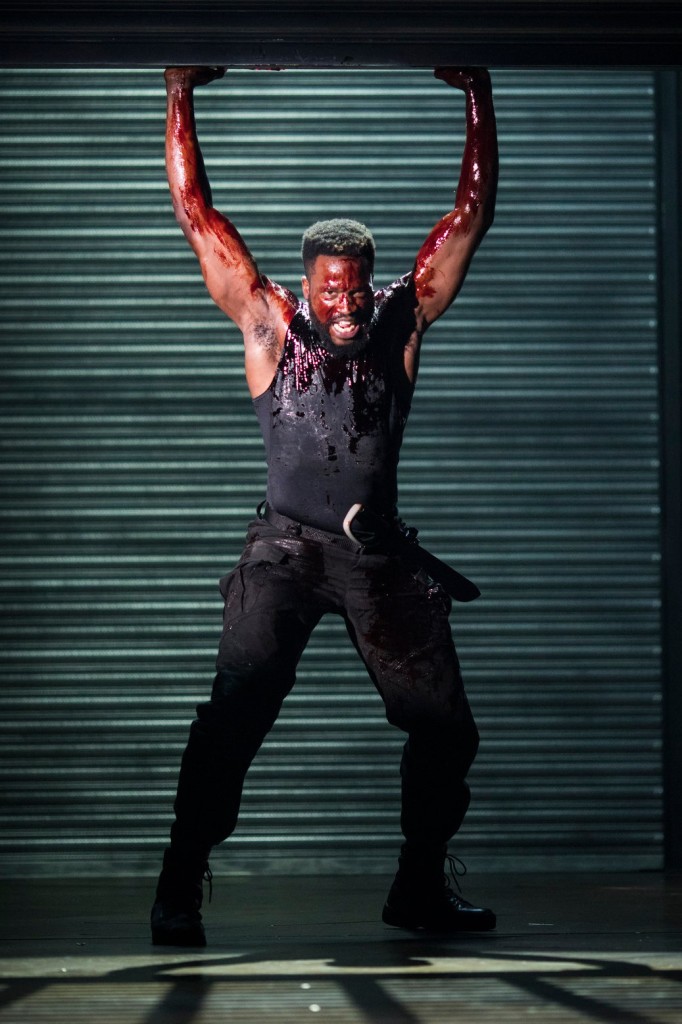

Given all these fine supporting acts, it is a shame that the central performance by Sope Dirisu as Coriolanus is, by RSC standards, poor. Dirisu has the physical presence for the role. His fight with Aufidius during the first half is about as brutal as stage fights can ever get without someone actually being hurt. But he is not at ease with the words. He speaks them clearly enough – no mumbling – but with almost no variation of pace or tone. The contrast with Gwynne, who breathes life into every line, is uncomfortably wide. Nor does he seem at ease in the play’s more private scenes, with Volumnia or his wife Virgilia. It’s just about possible to argue that his unbending demeanour is true to the character, but that seems to me like a cop-out: we need to see more of the inner man, and Dirisu gives us little.

The production has one other weakness worth mentioning, and that is the music, which is for a string group with an occasional solo voice. Stage music is often a bit clichéd, but at any rate it usually reflects the on-stage action. Unfortunately, here it feels out of place. I can think of one or two Shakespeare plays for which a string quartet with an occasional soprano would be fine, but Coriolanus, with its themes of confrontation and betrayal, is not one of them.

Coriolanus is not an easy play to love. The verse is knotty, with few memorable lines, and it lacks a sympathetic central figure: the tragic flaw which leads to his downfall is a bit too obvious. But it is a good drama for politically fractured times. I can imagine better productions, but I shall remember this one for the tribunes and for Haydn Gwynne, to whom I really hope the RSC will offer more roles.

——————–

The squad to tour Australia (part 2)

19 September 2017

(Continued from below)

I’ve never been a great fan of Jonny Bairstow as wicket keeper: I think he would do better for England as a pure batsman (incidentally, filling one of those difficult middle-order slots) and handing the gloves to a better keeper, probably Ben Foakes. But it isn’t going to happen, and though Bairstow’s keeping is still untidy, it has improved. With my plan Foakes would be the number 1 keeper with Bairstow as back-up, but I do not think it works so well the other way round. Foakes might be an adequate batsman for England at number 7 or 8 but nowhere near what is needed for the top order. All the hints are that Foakes will be selected but I think he will be twiddling his thumbs for most of the tour.

If Bairstow is to go as the preferred keeper, I would take Jos Buttler as back-up. Buttler gets a lot of criticism for his lack of playing time in long-form cricket. But he did well in India last winter when called into the side as an emergency batsman – better, in fact, than most of his top-order teammates. And I have in mind a piece by Vic Marks in the Guardian some months ago which said that Buttler is too rare a talent to be excluded. I agree with that. It will be a great shame if Buttler’s potential is never fully realised at Test level because he doesn’t fit into preconceived notions of form or role. He would certainly be in my squad.

The top four quick bowlers pick themselves but behind them there are several contenders, none of whom really stand out. Mark Wood played for England at the start of this summer but lost his place: on form he is as quick as anyone available but there are serious doubts about his fitness and stamina, and when his pace is down he offers nothing else. Jake Ball has played three Tests, most recently in India last winter, but for Australia he doesn’t offer much but honest hard work. Steve Finn, by contrast, has played more than 40 Tests, and for some years was our great fast bowling hope, but technical issues and a certain lack of confidence always seem to have held him back. He is 6’ 7” tall and one of his weapons has always been the bounce he gets: in theory he should do well in Australia. I would not pick him, not least because he had a disastrous tour last time England went to Australia, losing all confidence and form, and I think it would prey on his mind; but I suspect he will get the selectors’ nod, possibly ahead of Ball.

Fast bowlers tend to have short careers at the top (James Anderson being an obvious exception to the rule) and to get the best from them you may need to pick them early. For this reason I would choose Jamie Porter, who has already taken 68 wickets for Essex this season at 17.63, a main reason for the county’s Championship triumph. Porter seems commendably fit, and he would benefit from being in the same squad as Jimmy Anderson: he could potentially develop into a similar type of bowler and if he was half as successful could look forward to a good England career ahead of him. The selectors will think about Porter: I suspect they will prefer to go with the tried and tested Ball or Finn, but to my mind Porter is not just a better long-term prospect but also a better short-term choice.

The selectors will be well aware that in Australia swing and seam tend to be less effective than pace and bounce. That may keep Wood in their thoughts despite his obvious limitations, but they may also think about Liam Plunkett, arguably the most consistent Championship bowler to be taking wickets mainly through sheer hostility. He is also a useful lower-order batsman. I have seen more of Plunkett than most of the other candidates and I don’t think he is quite Test class, so he would not be my choice, but I would not complain too much if he caught the selectors’ eye.

But it is true that in Australia pace often is paramount, and for that reason I would be sorely tempted to take Somerset’s Jamie Overton, who I believe is the fastest England-qualified bowler currently playing. Somerset know his value and handle him with kid gloves: he is not selected for every match, and even so he has had periods out with injury. I would take a leaf out of Somerset’s book and take Overton on tour with the specific plan that he would play only at Brisbane and Perth where the pitches will be most responsive to sheer pace. He is certainly in the selectors’ minds, as he was chosen and bowled well for the England Lions earlier this summer, but they may be discouraged by his fitness record. I think with careful handling he could be a real not-so-secret weapon.

There are a couple of others who will probably be considered. Yorkshire’s tyro Ben Coad started the season like a house on fire, but his star has waned as Porter’s has risen. Bowlers who fare best at the start of the season but less well later are feasting on “English” conditions and likely to struggle in Australia. Coad’s turn may come, but not yet, and better for him if it comes in England. Surrey’s Tom Curran has been picked for England’s short-form squads and is a capable batsman, somewhere between Woakes and Roland-Jones in quality. Last time I saw him he was a bit lacking in pace, but if he has gained a yard or two he becomes a serious contender. Good judges say there’s something about him, which I translate to mean he won’t be put off by Australian sledging and will give as good as he gets. However, he hasn’t taken wickets in the same quantities as Porter or Coad, nor does he offer the pace of Wood, Plunkett or Overton. A near miss, I think.

Finally, the spinner. Whoever is chosen needs to complement Moeen’s attacking off-spin: that means a contrasting style, and steady accuracy. At the start of the year it looked as if Liam Dawson was the preferred reserve and we all groaned: he is not remotely good enough a bowler, and his workmanlike batting doesn’t compensate. However, for the West Indies Tests Mason Crane was preferred, and though he was twelfth man each time he is a much better choice. Crane is a leg-spinner with a nice easy action and an unusual amount of control. He doesn’t bowl lots of fancy stuff (top-spinners, googlies or flippers) but he varies his pace, line and spin subtly and well. And there’s something about him too. Last winter he took himself off, unsponsored, to play grade cricket in Australia, and ended up being selected for one of the state teams. That shows both character and talent.

The need for steadiness absolutely rules out Adil Rashid who went on the India tour. Rashid’s advocates point out that he was the most successful of England’s spinners on that tour, but that is an absurdly low standard: least unsuccessful would be a better description. Rashid’s leg-spin with multiple variations always stands a chance of taking wickets, but at an extravagant cost in runs conceded and loss of control. Tellingly there is no sign that Root, who plays alongside Rashid at Yorkshire, wants him in his team. A better bet would be Somerset’s slow left-hander Jack Leach, who might have been chosen for India but for two things: doubts about his action, now rectified; and a warning from his then county captain, Chris Rogers, that he was not yet temperamentally ready for Test cricket. Leach is a good bowler and his career stats are far better than Crane’s, but a spinner in Australia needs resilience more than anything, and for that reason I favour Crane. And the signs are that the selectors will do so too.

In summary, my squad:

Batsmen: Cook, Stoneman, Root, Malan, Hales, [Livingstone]

All-rounders: Stokes, Moeen

Wicket keepers: Bairstow, Buttler

Quick bowlers: Anderson, Broad, Roland-Jones, Woakes, Overton, Porter

Spinner: Crane

And my prediction:

Batsmen: Cook, Stoneman, Ballance, Root, Malan, Hameed

All-rounders: Stokes, Moeen

Wicket keepers: Bairstow, Foakes

Quick bowlers: Anderson, Broad, Roland-Jones, Woakes, Finn, Wood (if fit) or Plunkett

Spinner: Crane

There are some good videos on YouTube of the bowlers I have mentioned.

——————–

The squad to tour Australia (part 1)

17 September 2017

Now this summer’s Test matches are over, thoughts turn to selecting the squad of 16 or possibly 17 players who will tour Australia this winter to play five Test matches. Let’s start with the certain selections. By my count there are nine:

Batsmen: Cook, Root

All-rounders: Stokes, Moeen

Wicket keeper: Bairstow

Quick bowlers: Anderson, Broad, Roland-Jones, Woakes

That leaves space in the squad for three, probably four more batsmen, at least two of whom should be openers; a reserve wicket-keeper; one or two more quick bowlers; and a specialist spin bowler. If the selectors decide to take only 16, they may omit a fourth batsman or a second extra quick bowler – my list of certainties already includes one reserve. The England Lions will also be touring Australia, to provide a ready back-up, but not close enough if a replacement needs to be brought in on the morning of a match.

The team for England’s most recent Test included three other batsmen: Stoneman (opener), Westley and Malan. I think Stoneman is almost certain to be selected, rightly so. There is nothing obviously wrong with his temperament or technique. In his first three Tests he scored 8, 19 and 52, 1 and 40 not out. Only once was he truly guilty of a mistake that cost his wicket; for each other dismissal, credit must go to the opposition. Most impressively, after the third Test he returned to Surrey and made a chanceless century which suggested he had raised his game to a new level. He is learning, and could do well.

Malan was a left-field selection originally, chosen ahead of several others who might have deserved it more, and to begin with I thought he might prove like James Vince last year: too loose, too flashy, too easily lured into indiscretion. But in fact he has shown he can restrain himself and make ugly runs when the occasion demands, especially his 61 off 185 balls spread over nearly five hours in the second Test against the West Indies. He would not have been my original choice, but now he’s there he has done enough to silence his doubters (for the moment at least) and keep his place. He would be in my squad and I think he will be in the selectors’.

Westley is another kettle of fish. He played five Tests this year, replacing Gary Ballance at number 3, which is a problem position for England. So he was thrown in at the deep end. But you only have to watch him for a couple of minutes to see his weakness. He takes guard on off stump and tries to hit as much as possible through the leg-side using a strong bottom-handed grip. It is an obvious technical flaw which international opponents are sure to have noted, and perfectly set up for the Australians’ quick bowlers to exploit. I fear the selectors may regard him as their man in possession, but he would not be in my squad and he will be a weak link if he goes to Australia.

If not Westley, I think the selectors may be tempted to go back to Gary Ballance, whose form for Yorkshire at the start of this season demanded a return to the England team. He played two Tests before he was injured but did nothing to suggest that he has amended the flawed technique, stepping a long way back towards his stumps, which Test bowlers had previously exposed and led to him being dropped last year. It would appear that England captain Joe Root favours Ballance’s selection, and given the absence of other compelling candidates that may be enough to tip the scales. But the Australian quick bowlers will have noted Ballance’s technical flaws, no less than Westley’s. He does at least have the temperament for the long game and I think he would be a better choice than Westley, but not by much. My prediction is that he will be chosen ahead of Westley, but he would not be in my squad.

If the selectors choose all of Stoneman, Malan and either Ballance or Westley, they will need another opening batsman too, and in the absence of other obvious candidates I am very afraid that they will take Lancashire’s Haseeb Hameed. At the start of 2016 Hameed was widely admired for his technical skill and mature temperament, but there were doubts about his slow rate of scoring. He is slightly built and depends on timing much more than muscle. But during the year his fluidity developed, and when I saw Hameed batting in the Roses match there was no doubt that he was a future star.

He was selected for England’s tour of Bangladesh and India last winter, and made a favourable impression across the board. But then he sustained a serious injury: his hand was broken so badly that he needed surgery and the insertion of a metal plate. And this season his form for Lancashire has been dire, only recovering slightly in the last few weeks during which he has made a handful of painstaking half-centuries. The smooth progress which he made during 2016 has gone and only now is he rediscovering the judgement, mature beyond his age, which made him such a sensation last year.

I don’t have any doubt that Hameed has a long England career ahead of him, but especially given the injury which has triggered such a setback I do not think he should be reintroduced until he has regained the fluidity which was so apparent in the second half of 2016. It is clear this is much a matter of time and confidence as anything, but premature selection could put at risk all the ground he has regained this year. If not selected for the Test squad, he will go on the Lions tour for sure.

There are numerous other candidates around the counties, including Keaton Jennings, who started 2017 as the preferred opener but seems to have lost all form and confidence; Nick Browne, who has made over a thousand runs for Essex’ championship-winning side, but has not so far been recognised by the selectors; and Sam Robson, who played for England three seasons ago with indifferent success (though he did make one century) but is now by all accounts a more complete batsman. Robson played for the Lions against the South Africans without distinguishing himself, and seems the most likely alternative to Hameed. Last year Middlesex’ Nick Gubbins would have been a strong candidate and narrowly missed out on the India tour, but he has spent the second half of this season injured and must have lost a bit of ground because of that.

In any event I think another option is available. Alex Hales opened the innings in all of England’s home Test matches last year, and started well against the Sri Lankans before fading against Pakistan. He missed the tour of Bangladesh and India, a good non-selection in my opinion: Hales’ weakness as a batsman is that he doesn’t move his feet much, and this leaves him vulnerable against swing or spin. India would have given him a hard time. But in Australia the challenge will all be about pace, and Hales is comfortable against quick bowling. In this year’s County Championship he has been batting in the middle order for Nottinghamshire, and that appears now to be his preference. But he could be selected for the tour primarily as a middle-order batsman with the ability to step in as an emergency opener should the need arise. He has continued opening the innings for England in short-form cricket with great success, so the role should not be too unfamiliar to him.

With Stoneman, Malan and Hales in the squad I am not sure that a fourth batsman would be needed: Bairstow, Stokes and Moeen are all capable of batting in the top six should the need arise. But if a fourth batsman were added, I would look to one of the younger generation: most likely Lancashire’s Liam Livingstone who has already caught the the selectors’ eye and is a brilliant fieldsman too, but also Essex’ Dan Lawrence who has the ability to bat long innings against tough bowling and could easily be an England number 3 in the making. Neither has Test experience and it would be tough to take them untried on an Ashes tour, but to my mind either of them would be an improvement on Ballance or Westley. There is also Kent’s captain Sam Northeast, who has been making big runs for Kent over several seasons, and impresses good judges – but Kent are a second division team and no-one really knows how Northeast would fare against top-class attacks. The selectors will think about him, but I should be very surprised if he made the trip. Captain of the Lions, possibly.

(To be continued)

——————–

Follies

16 September 2017

Georgina and I went this afternoon to see the National Theatre’s new production of Stephen Sondheim’s 1971 musical, Follies. The show is produced only rarely, for understandable reasons. It demands at least four principal actors who can sing and dance, at least three other top class singers, and a cast of more than 30, plus a conductor and an orchestra of 15 players. And it requires a lavish set and costumes. The NT sent out begging letters beforehand to members and subscribers (I received one) asking for money to help put on the show.

So this was a brave undertaking by the NT: the more so, since Follies has always divided opinion. The influential theatre critic at the New York Times, Clive Barnes, wrote in 1971: “… it is stylish, innovative, it has some of the best lyrics I have ever encountered,” but he also called the story shallow and Sondheim’s words a joy “…even when his music sends shivers of indifference up your spine.” He was wrong about the music however you look at it, but as for the story… well, we will come to that.

Georgina and I both thought it was great. I’ve written previously that as far as I’m concerned it is the music which makes or breaks a musical: but with Sondheim I thought I would be on safe ground, and so it proved. The orchestra, unseen backstage, are top class, well conducted by Nigel Lilley who allows no slackness in Sondheim’s sharp rhythms. The principals all sing well – in some cases, unexpectedly so: by and large these are actors who can sing, not singers who can have a stab at acting, but they perform Sondheim’s clever, fluid lyrics and unsentimental melodies to the manner born.

The basic idea of Follies is that on the soon-to-be demolished stage of the Weismann Theatre, a reunion is being held to honour Weismann’s “Follies” shows and the beautiful chorus girls who performed there every year. This is clearly inspired by the real-life Ziegfeld Follies which played in New York between the wars: revue-type shows which were famous for their display of beautiful chorus girls, lavishly but (for the day) revealingly costumed. However, overlaid on this is a character study of four principals: Sally and Phyllis, who used to be Weismann girls, and their respective husbands Buddy and Ben. We also get a brief insight into how other girls have managed in their post-Weismann lives.

There is one other conceit central to the show. Each main character is represented by two actors: one as their present-day selves, another as a ghost of how they once were. The ghosts haunt the action, sometimes taking part or playing out a scene which is being recalled, but often also as mute spectators. This sounds like a clumsy, stagey device, but in fact it is in the original stage directions, not just devised for this production, and it works brilliantly.

Follies is not a through-composed show: there is a good deal of spoken dialogue, especially in the first half. The programme lists 22 separate musical numbers, and I’d guess that roughly half of these are loving pastiches of the classic Broadway chorus style. For these the production really goes to town, with intricate, extended choreography. The principal actors/characters may be, shall we say, in mid-career, but they are not spared: they not only sing, but dance too, and are put through their paces – though I did like how the demands is toned down for the older characters, even in ensembles, thus hinting at the melancholy of ageing which is one of the show’s themes.

In the best numbers, the ghost doubles also participate. I particularly enjoyed Mirror, Mirror (correct title: Who’s That Woman?), a real show-stopping routine in which the principals and their ghosts are interwoven. This and other set-piece numbers brought waves of applause from the audience.

Alongside, Sondheim gives us a set of essentially solo numbers in which former Weismann girls reflect on what they were and are. All of these are well sung and acted: Di Botcher in Broadway Baby, Tracie Bennett in I’m Still Here, and Josephine Barstow (a true opera singer, one of two in the cast) in One Last Kiss.

Dame Josephine plays Heidi, the oldest of the Weismann girls, and in truth she looks frail, but she still has a clear, pure soprano, with thrilling top notes. Her solo – in fact, a duet with her ghostly former self – demonstrates Sondheim’s musical facility: it has all the harmonic and melodic touches you might expect in an operetta by Léhar or an orchestral song by Richard Strauss or Korngold. This number, more than any other, conveys the melancholy of time we know has passed, but without the regret or rancour or defiance displayed by other characters.

The story of the four principals emerges slowly, and we have to piece it together from minor incidents and flashes of dialogue and action. A picture emerges: courtships disrupted by war, marriages soured by time, disappointment and infidelity. The reunion brings it all back, passions are roused, weaknesses laid bare. Sally is neurotic, Buddy keeps a mistress, Phyllis has casual affairs, Ben loves no-one but himself. Phyllis hates Sally but wants what she thinks she has; Sally loved Ben, and thinks she still does. All are unfulfilled. One Guardian blogger puts it this way: “The characters: gut-wrenchingly awful, self regarding, navel-gazing, philandering monsters, none of whom anyone could possibly like… two and a quarter uninterrupted hours of these dreadful characters is almost enough to put you off the great songs.”

This is ungenerous. Follies isn’t just about the melancholy of ageing and how we variously deal with it, but also about the wrong turnings we take and how we are haunted by the past. Those ghosts are not just a device; they are part of the plot. The principals didn’t start off as self-regarding, navel-gazing, philandering monsters, but we see a bit of how they got that way. Who wants to see a play, or a musical, about unremittingly virtuous, contented people? And in any event only about a third of the show, perhaps less, is concerned with these four.

But it is true that this strand in Follies is wafer-thin. It is more a situation than a plot. And it is not fully integrated into the rest of the show. Having been in the background for the first hour and three quarters, present but not prominent, it suddenly takes over the stage for the last half hour. According to the programme notes, Sondheim worked on and off on Follies for many years, going through numerous rewrites and at least one major plot change (it was originally intended as a murder mystery – hard to believe, but true). Even in its relatively short performing history several different versions have been produced, with various numbers added or removed. I wonder whether it may have been over-worked, losing sight of the wood for the trees.

In any event this is still a terrific show. The two female leads, Imelda Staunton as Sally and Janie Doe as Phyllis, are outstanding. Staunton is too short to be entirely credible as a chorus line star, but who cares? She conveys Sally’s sparky, neurotic character perfectly. And she is well matched by the hauteur of Janie Doe’s Phyllis whose acidly scornful number Could I Leave You? is another show-stopper. The male leads, Buddy (Peter Forbes) and Ben (Philip Quast) get a little less solo work, but are also convincingly in character, and Ben’s final number Live, Laugh, Love in which he appears to break down on stage has you momentarily wondering whether it is acted or for real.

The title of Follies is clearly a homage to Ziegfeld. But it is also a reference to the follies of youth and age. The plot, such as it is, is imperfectly integrated into the show, but the theme of time’s passing comes through clearly, and despite the mostly upbeat music there is an undercurrent of melancholy running clearly throughout. Follies’ run in the theatre is already almost completely booked out, but it will be shown live in cinemas across the UK on 16 November as part of the NT Live programme. Don’t miss it.

——————–

Panic

4 September 2017

Coming home by train from Barcelona last Thursday, I had a most uncomfortable day. You must make up your own mind whether it shows the descent of old age, an unfortunate family trait inherited from Dad, my own special brand of misadventure, or genuine bad luck.

It started in the morning after I left the apartment where David, John and I had been staying and caught the Metro to Barcelona Sants. I carelessly misread the map and got off at Plaça de Sants, which is not the right stop. I should have gone to Sants Estació. Fortunately this mistake was easily remedied as I had allowed plenty of time – all I had to do was catch a different Metro line for one stop back to Sants station. But by throwing me off balance it did prevent me from doing as planned and buying some food for the journey before I boarded the TGV for Paris.

I was still a bit thrown when, after half an hour, I went to the restaurant car and bought a sandwich I didn’t want (ham and camembert, toasted – it smelled disgusting) and an espresso instead of an orange juice. To make matters worse, just as I was getting back into my seat I tripped over my bag and spilled the espresso over the new book on Modernism which I had intended to give John at Christmas. I spoiled a good handkerchief mopping that up. At least I had the bottle of water which I had brought from the apartment. But the disgusting sandwich went straight in the bin.

The train was fine, and although I had been given a seat on the lower deck (these trains are double-deckers) my view was fine: it was no worse than on an ordinary train in England, and a good deal more comfortable, despite the espresso smell. But after we pulled out of Valence TGV, the last scheduled stop before Paris, the train slowed down and I started to notice odd things – sidings with trucks in them, farmyards backing on to the line, level crossings, and finally a junction on the flat with another line. We semed to have left the high-speed network, and when we drew into Lyon main line station I was sure of it.

This was alarming. Would we be running slow(ish) all the way to Paris? In other circumstances I would have been quite pleased to have a view of Lyon’s railways – it is one of the most important junctions on the French network – but I was too distracted to pay much attention. However, by decoding the messages in French which were shown on the video screens in the carriage, I eventually managed to work out that we had been diverted because of a suspect package at Lyon TGV station which was being investigated. The train was likely to be delayed by 50 minutes.

At least this explanation provided some reassurance. My schedule allowed almost two hours to cross Paris before my check-in time for the Eurostar, and 50 minutes’ delay, though annoying (not least because I was getting quite hungry by now), was tolerable. And, after all that has happened in the last few months, the train company could scarcely be blamed for being cautious. We regained the high-speed line not far north of Lyon, and the rest of the journey to Paris was uneventful.

I was at the back of the 18-coach train and when we reached Gare du Lyon I had a very long walk to the main concourse. There seemed to be some kind of French demo taking place, with men in high-visibility jackets waving placards and chanting, and brass instruments blaring out. So the crowds were a lot worse than on our journey south. I thought I had better head straight for Gare du Nord and not stop to refuel until I was there.

David, John and I had had a rather unsettling time a few days earlier when we transferred between Gare du Nord and Gare de Lyon on the RER suburban train, and I did consider opting for the slower Metro option, but decided that this was a bit cowardly. That was a bad decision. I’m sure regular users of the RER know which trains go from which platforms, but for the uninitiated they are not well signed, and I wasted five minutes on the wrong platform before working this out.

But I did manage to board an RER train going in the right direction, and then came the final, and worst, of the day’s challenges. There is one intermediate stop on the line, Châtelet-les Halles, which according to Wiki is the largest underground station in the world: it has three RER lines on a total of seven tracks, and five Metro lines, each with its own pair of platforms. Before our train could reach Châtelet it stopped in mid-tunnel for about ten minutes, which would have been quite alarming anyway (since I could not understand a word of the on-board announcements) even if I had not by now felt in a bit of a hurry. Eventually it moved into Châtelet and stopped again.

I had meanwhile struck up a conversation in halting French with a fellow passenger standing in the train vestibule, a middle-aged woman, elegant in a very French style, who was wheeling a large suitcase. Anxiety lent wings to my French vocabulary. I was once told that my French accent is impeccable – yes, by a French-speaker too – but I had to explain to her that though I can read French passably I can’t understand it unless it is spoken very slowly, or remember more than a few words on my own account. She said that no, this delay was not normal, but apart from that she didn’t seem to know any more than I did.

After another ten minutes in Châtelet I had had enough. We could be stuck here for half an hour or more; better try the Metro. I picked up my bags and ran up the stairs, stopping on the way to consult a convenient map which was pasted on the wall, and went through the exit barriers. First thing was to get a new ticket: where were the ticket machines? As David and John will confirm, Paris has the most complicated, illogical ticket machines on Earth, but eventually I managed it. Line 4, that was what the map had told me I needed, and it went direct to Gare du Nord. But where was Line 4? I could find signs to all the other lines, but not that one. By now I was getting a bit panicked. I ran up and down, crying out (I think in a mixture of French and English) “Where is Line 4?” No-one answered, though I have an idea there were some funny looks. Those Englishmen (you could tell I was English, because of the hat), they are all mad, n’est-ce pas?

Eventually I found the right platform and the train came quite quickly. 15 minutes still to go before the check-in deadline, and there were six stops en route. But at least I knew where to go when we reached Gare du Nord. All I had to do was get to the first-floor balcony overlooking the main line station: that is where they carry out the security and passport checks. I dashed off the Metro train and up two flights of stairs to ground level, one bag slung over my shoulder, the other in my hand. By now I was seriously short of breath. I was afraid I would collapse on the floor before I could manage to cross the concourse and climb the last flight of steps.

However, I made it. I got through the border checks without difficulty … only to find that my train wouldn’t even start boarding for another ten minutes. I spent those ten minutes in recovery, too exhausted to seek refreshment. At least, when the train started, my carriage was the first to be served dinner. Boy, I needed that dinner. And credit to Eurostar, it was good, with a generous slice of French quiche, a piece of aubergine folded over some sliced peppers and a bread roll, plus a nifty little bottle of red wine, coffee (unspilled) and a bottle of water.

My adventure was over. But the unaccustomed exercise has had its price: my muscles have felt stiff, when I stand up or start to walk round, ever since. Would I go by train again? Yes, probably. I still prefer stations to airports. But I have abandoned the RER for ever.

——————–

Barcelona : Picasso and Miró

4 September 2017

During our visit to Barcelona, John and I visited both the Joan Miró Foundation and the Picasso Museum. We also had in our minds our visit to the Reina Sofia in Madrid earlier this year, which I described in a blog on 18 June, and the major exhibition of Miró’s work which we saw at the Tate Modern in 2011.

In some respects the Foundation and the Museum could not be more different. The Foundation is a purpose built gallery, all concrete and glass, with a wide range of Miró’s work from all of his working life, beautifully laid out. It was commissioned by Miró himself from an architect with whom he collaborated to create a space for the exhibition of his own work and as a centre for other contemporary art and research. In fact, almost everything we saw was Miró’s own: mostly paintings, but also some ceramics (not very interesting, we thought), a kind of knotted tapestry (very striking colours, but a most peculiar object), and a few sculptures which meant nothing to me (but that is an art I have never pretended to understand). There was a temporary exhibition of some other new work: we gave it a quick glance, and passed on.

The Picasso Museum is in five town houses knocked together in Barcelona’s Gothic quarter, where the buildings are old and higgledy-piggledy, full of unexpected alleys, arches and courtyards. As a building it has a lot more character, and perhaps this is appropriate, because it focuses on Picasso’s roots in, and connection with, Barcelona and Catalonia. Thus it has a very large collection of Picasso’s early work but a good deal less from his later life (after 1910 or so), what there is being very patchy in coverage: nothing as famous or easily recognisable as Guernica, which we saw in Madrid. So there is much less sense of his full career.

If I found the Picasso more interesting, it was not only because Picasso is, of two great artists, the greater. Walking through the early rooms you can see Picasso experimenting with various styles which would have been considered modern at the time; mostly impressionist, reminiscent variously of Renoir, Monet or Cézanne, but also numerous portraits and at least one large-scale painting in a more traditional style, Science and Charity, which won him acclaim and prizes. Yet behind this versatility you can sense a restlessness, as if Picasso felt that, for all his precocious mastery, he had not yet marked out his own path.

Of course this may be the wisdom of hindsight. Picasso was enormously prolific and extraordinarily versatile. Art historians can chart various periods during his life when one particular style or theme or image dominated his work, but he does not seem ever to have rested on his laurels. Knowing this, I may possibly be reading more into the Picasso Museum’s exhibition of his early work than is truly present. But in any event I felt that the collection gave me an insight into his development.

Picasso’s later work is not totally absent from the Museum. His versatility is demonstrated by a small group of paintings from a visit which he made to Barcelona in 1917. Harlequin is almost naturalistic; Blanquita Suarez has a strong Cubist flavour; the Passeig de Colom has numerous touches typical of his later work with its stylised, almost childlike representations and multiple overlaid perspectives.

And his facility is shown by his Las Meninas series, 58 works painted within four months in 1957, which reinterpret and recreate parts of a painting by Velasquez. I confess that this was the exhibit which gave me the most trouble, as I could not grasp what Picasso was trying to achieve here, but the sheer productivity still amazes.

By contrast, the career retrospective provided by the Miró Foundation offers only a small selection from the artist’s early work, and his change to a semi-abstract, symbolic style, with hints of surrealism, comes suddenly. The paintings alone give no hint of how this occurred; there is nothing here like his painting The Farm, which we saw at the 2011 exhibition and shows how his art is starting to evolve.

You have to read the commentary which accompanies the Foundation’s exhibits to learn that Miró fell into avant-garde company whose influence seems to have totally changed his style of work. Unfortunately, the texts are also more than usually pretentious, which makes it hard to extract the nuggets of real information from them. There are various references to Miró’s claim that he was working towards the assassination of painting, which – even allowing for nuances lost in translation – struck us as both ironic and ridiculous.

This is not to say that his mature work, with its extensive use of symbols devised by Miró himself, is unappealing. From the 2011 exhibition I remembered that he had produced a series of abstract works with the general title Constellations, and sure enough, one of the paintings from that series, Morning Star, may be seen at the Foundation. The intricate pattern of lines, symbols, primary colours and background shading is both attractive and fascinating. I believe that Miró scholars have decoded his symbolic language and that pictures such as this may have a meaning, or at least a reference point; but I am happy to remain in ignorance.

Unfortunately, it seems to me that Miró’s work gradually deteriorated, from true vision to empty rhetoric. Another picture in the exhibition, Figure in front of the Sun, illustrates this: it is more coarsely painted, and to my eyes lacks any real interest.

I do wonder whether the rather uninteresting ceramics reflect a desire to use this new medium to reawaken the inspiration which has gone from his paintings. If so, I don’t think they were very successful. In the end, I suspect that Miró did indeed rest on his laurels. Work like the Painting on a White Background (1968) is not so much an assassination as a mockery: the kind of thing which gets modern art a bad name.

——————–

Barcelona : Gaudí and Güell

3 September 2017

When we visited Madrid we paid particular attention to the art; but in Barcelona it was the architecture. Barcelona was the home of the architect Antoni Gaudí, and most of his surviving works are to be found there or close nearby. Many were undertaken thanks to commissions or sponsorship from the industrialist Eusebi Güell, and their two names are closely linked.

On our previous trip to Barcelona, John and I visited what is undoubtedly Gaudí’s unfinished magnum opus, the Sagrada Familia church, which has become an icon of the city. It is, in the proper sense, an awe-inspiring building. I think John would have been happy to see it again. But the problem with the Sagrada Familia is that it is so popular. Even if you book in advance there are queues to be endured, and when you get inside there are great crowds to be negotiated. And besides, there were plenty of other Gaudí sites we had not yet visited. So we gave the Sagrada Familia a miss this time.

Our greatest regret on our previous trip (when we did not know that we would be returning) was that we failed to visit the Parc Güell. This is located on one of the hills in the north of the city, and was conceived by Güell as a kind of garden village for Barcelona’s growing elite, with its design overseen by Gaudí. Alas, Güell’s vision was not widely shared and only a small handful of buildings were completed, the rest remaining as parkland. So the Parc Güell is mostly just what it says, a park, with a striking view out to the south over central Barcelona and towards the sea. But at its centre is a small estate of Gaudí buildings, showing many of his most notable characteristics.

Our greatest regret on our previous trip (when we did not know that we would be returning) was that we failed to visit the Parc Güell. This is located on one of the hills in the north of the city, and was conceived by Güell as a kind of garden village for Barcelona’s growing elite, with its design overseen by Gaudí. Alas, Güell’s vision was not widely shared and only a small handful of buildings were completed, the rest remaining as parkland. So the Parc Güell is mostly just what it says, a park, with a striking view out to the south over central Barcelona and towards the sea. But at its centre is a small estate of Gaudí buildings, showing many of his most notable characteristics.

Perhaps I should say what those seem to me to be. In the first place Gaudí didn’t like straight lines, especially in the vertical. He much preferred curves, and had a particular liking for the catenary arch which appears in several of his buildings. (A catenary arch is an upside-down catenary curve, which is the curve that an idealized hanging chain or cable assumes under its own weight when supported only at its ends. It is not the same thing as a parabolic arch, but don’t ask me why.)

In the Sagrada Familia the columns have twisting shapes and many of them branch out at their tops, like the branches of trees. Gaudí liked to mimic natural forms, but he was also a precise geometrician and accurate model-maker: apparently the builders who worked for him were used to taking their instructions not from plans but from scale models in which the details had been carefully worked out. Many of these were destroyed after his death, but modern copies are on display at the Sagrada Familia.

Gaudí was also fond of decoration. He had a particular liking for the Catalan trencadis style, which uses broken pieces of ceramic to form a mosaic, and is particularly suited to the curved surfaces Gaudí preferred. The trencadis dragon (another icon!) which guards the steps leading up to the portico at Parc Güell is a good example. And clearly related to this is a love of stained glass, again best seen at the Sagrada Familia, which has the most beautiful such glass I have ever seen in any building anywhere. Only a small part of this was done by Gaudí himself, but enough (together with the instructions he left) for others to complete.

You might in fact say that one of Gaudí’s principal characteristics was an obsession with detail. He wanted to do things differently, but he also wanted them to be right. The second Gaudí building which we visited, the Casa Batlló, is a good example. He did not design the original building, but he oversaw a complete remodelling. There were new curved wooden frames and new stained glass for the windows of the principal first floor room. (Note also the spiral decoration of the ceiling; not like anything else in my experience.)

The central light well was opened out and retiled in blue, with lighter tiles at lower levels to ensure an even distribution of light on all floors. He designed the furniture, the pillars and screens, the door handles, the light fittings and the fireplaces. The loft has some perfect examples of catenary arches, and is cunningly designed to assist ventilation of the whole building – again, don’t ask me how. There are some straight lines – of course there are; but there are more curves than any other architect then, or I dare say since, would have included.

Above all, he made the roof interesting, reshaping and retiling it to resemble a dragon’s back (the dragon is an important figure in Catalonian folklore). Gaudí clearly loved roofs. In two other buildings which we saw on our previous visit, the Palau Güell and the Casa Milà (La Pedrada), the roof decorations are even more elaborate and fantastic. I do wonder how much this was for his own satisfaction, how much for the owners’; and whether he expected his roofs ever to be seen, except of course by God.

All these buildings are in the city itself. But for our last afternoon in Barcelona David was able to join us, and we decided to make a short expedition out to Colonia Güell, in the town of Santa Coloma de Cervelló, fifteen or so miles to the west and easily reached on a suburban train. With the Güell name you would expect there to be a Gaudí involvement, and so there is.

Colonia Güell is in fact an industrial village created by Eusebi Güell, whose money was made in the textile trade. He wished to promote the well-being and contentment of his workers, and at Colonia Güell built for them a complete community. His factory was on one side of the site; on the other were the workers’ houses, a meeting-place, the church and (unusual in those days) a school. In England, Port Sunlight and Bournville were founded by the Lever and Cadbury families, respectively, along the same lines. Whether you think this was done for humanitarian reasons, or simply to manage the risk of unrest and disease affecting production, depends on how cynical you are; probably it was a bit of both. For the time it was, in any event, quite forward-thinking.

Gaudí was commissioned to design and build the church, and Güell, as usual, seems to have given him more or less a free hand. Gaudí spent years working out the design, which was eventually for an oval church on two levels with a ramp to the upper level, two towers, a tall belfry with a polygonal floorplan, large stained glass windows, and a porch with hyperboloid vaulting (don’t ask).Unfortunately, by the time work eventually started Güell was already ailing, and after his death in 1918 his sons stopped the project. Only the vault, the lower level, the ramp and part of the belfry had been completed. Nonetheless, this was enough to allow the church to be consecrated and it is still in use today.

The Crypt of Colonia Güell, as it is now most often called, exhibits in miniature most of the hallmarks of Gaudí’s style. It was the last of his major works before the Sagrada Familia. Yet when we visited there were barely another half dozen people at the site. There is little advertising, and it does not appear in many of the most popular tourist guides. Even if there were nothing but the Crypt to see, it deserves more attention. As it is, the authorities are evidently trying slowly to develop the whole of the Colonia: for instance there is work under way to restore the school as a tourist site. We found a rather languid information office, where we were each loaned an audio guide – informative, but could have been much more so. When you consider the crowds at the Sagrada Familia and the queues at La Padrera, there is something out of balance.

The reference sources say that Gaudí has been influential in the development of modern architecture. If that is so, his influence is pretty much invisible to my untutored eye. The curved forms of a Gaudí building, the decorative styles, the attention to detail – they all seem to me to be sui generis. Gaudí may have been an obsessive perfectionist, but he was also a genius, and Güell deserves credit and our thanks for enabling his ideas to flourish.

——————–

Barcelona

2 September 2017

David, John and I have just spent the last few days in Barcelona: David attending a conference there, John and I staying with him in an apartment he had rented and enjoying his company in the evenings.

This was our second trip to Spain this year, after visiting Madrid in June, and this time we travelled there by train. We left Oxted at twenty past seven and arrived into Barcelona just twelve hours later. From St Pancras, the journey was quite straightforward: Eurostar to Paris Gare du Nord, RER suburban train to Paris Gare de Lyon, TGV from there to Barcelona. We travelled first class so were fairly comfortable, though tired when we reached our destination.

Within a couple of years the TGV stage will be faster. At present the train runs, rather slowly, on the “classic” (ie not high-speed) network along the south-western coast of France from Nîmes to Perpignan and takes two and a half hours to do so. When the new high-speed line from west of Montpellier to east of Nîmes is complete it should knock half an hour off the timings. The final missing piece in the TGV route, from Montpellier to Perpignan, is still the planning stage and won’t be in service for several years, but when it is Barcelona will be in easy reach from Paris – as easy as Edinburgh from London – and train from London to Madrid will be imaginable.

Anyway, we got to Barcelona safely enough, and had the easiest transfer to our apartment that we have yet managed on any of these short holidays with David. This was the fifth: previously we have been to Amsterdam, Barcelona, Paris and Madrid, and on each occasion there has been some delay, either with transport, or with finding the address, or with getting someone to let us in, which is a bit stressful after a long journey. So that was good.

Lots of people rave about Barcelona, saying it’s their favourite foreign city / tourist destination / hangout. After two visits, I still don’t quite see it. But Barcelona does seem to have something for everyone, and perhaps that’s the reason for its popularity. Few visitors will be completely bored. I will be writing separately about our visits to the Miró and Picasso galleries, and about our encounters with Gaudí’s architecture which is perhaps Barcelona’s most distinctive feature; but that still leaves plenty to talk about.

For one thing: we ate six tapas dinners, in four different restaurants, and every one of them was excellent. Even in Paris the overall standard was lower. Whether I would have been quite so satisfied after a month, I’m not so sure. The tapas menu is a little unvarying from place to place, and there is only so much interest to be found in the different ways of cooking patatas bravas (spicy potatoes) or padron peppers (little green peppers fried with salt). But David said that the fish dishes, especially octopus, were outstanding; and the chorizo sausage, which I think we ate in three different forms (slices, mini-sausages, minced meat) was equally good. True vegetarians, eating neither meat nor fish, might have a hard time, though.

John and I did a good deal of walking around from one attraction to the next. Barcelona is home to the famous Las Ramblas boulevard, on which there was a terrorist atrocity just a couple of weeks ago. The police were out in force here, and the pavement tributes, with flowers, candles, teddybears and placards, were quite poignant; but no-one seemed to be behaving any differently from normal. On our Saturday in the city there was a large, well-publicised official demonstration in the main square, next to Las Ramblas, whose general theme was We Are Not Afraid; which, so far as I could see, seems to be true.

To the east of Las Ramblas is the Gothic quarter, where we spent a good deal of time on our previous visit, not so much this time; and beyond that a lively park where among other things are a nineteenth-century Arc de Triomf in red Catalan brick and a stone mammoth. To the west is Montjuic, a hill with a funicular railway and gondola-type cable car to get you to the top; to the north is the Parc Güell of which I will write separately.

To the east of Las Ramblas is the Gothic quarter, where we spent a good deal of time on our previous visit, not so much this time; and beyond that a lively park where among other things are a nineteenth-century Arc de Triomf in red Catalan brick and a stone mammoth. To the west is Montjuic, a hill with a funicular railway and gondola-type cable car to get you to the top; to the north is the Parc Güell of which I will write separately.

In between, outside the Gothic quarter, the streets are laid out mostly in a grid pattern, with extensive one-way traffic systems except on the widest boulevards. Traffic seemed a little lighter than in Madrid (perhaps because it was August) and much lighter, with less pollution and aggravation, than Paris. There were a few unsavoury-looking types hanging around, but I guess you get that in any city. Walking around, I was neither gasping for breath nor fearing for my safety.

Barcelona also contains some interesting railways. (Non-enthusiasts may look away now, and come back after the next photograph.) There are three different track gauges: the old Spanish broad gauge (5 ft 6 in); standard gauge, used for the new high speed lines and gradually being extended to other lines; and metre gauge for some services running west from the city. In the last 30 years Barcelona Sants has become the main station, served by standard and broad gauge lines which run underground and permit through traffic from east to west.

John and I also briefly visited the other main station, Barcelona França, which was the main-line terminus before Sants was developed, but now seems a bit of a backwater with only three of twelve platforms in use when we were there. It is a far more beautiful station, with a high cast iron arched roof, but now has an air of faded grandeur, a bit like some of the main line stations in the United States. I hope they find a new use for it, just as Eurostar has brought new life to London’s St Pancras station.

Apart from art, architecture and food, our main engagement with Barcelona’s cultural life was on Saturday evening, when we went to a concert of Flamenco music and dance at the Palau de la Musica. This is a concert hall around which we had enjoyed a guided tour on our previous trip: it has gorgeous Art Nouveau decoration, in particular a stunning inverted-dome roof, and we were very keen to hear some music there. In truth, Flamenco wouldn’t have been my first choice; but if I was ever to hear a Flamenco concert, what better opportunity than this?

The concert was led by a guitarist, Pedro Javier González, obviously well-known to the audience. He played his first item solo, and then introduced, in stages, a bassist, a second guitarist, a percussionist and two Flamenco dancers, male and female. The dancing was definitely Flamenco, with a lot of stamping and gesturing. It was impossible to say how much was rehearsed and how much improvised, but John observed that both dancers, especially the man, had a fairly restricted range of moves, though within that range they were very good. We were sitting on the top tier of the concert hall and my view of the dancers, who were performing in front of the musicians, was a bit restricted; but if you have ever seen Flamenco dancing on film, this would have held no surprises.

As for the music, if that first item was, as I suppose, pure Flamenco, its possibilities seemed to me rather limited, with a constant start-stop pattern, each phrase ending with a strong guitar chord and a pause. There is a definite tang of dissonance to the Flamenco harmonies, but it is unvarying, and the music does not develop or build momentum in any way that I could recognise. I was afraid I would be very bored by the end of the evening. However, as the concert continued, the Flamenco element gradually became more diluted, and it was possible to admire the undoubted virtuosity of the playing without being put off by the music. Near the end, González and his group played a version of Dire Straits’ Down to the Waterline, after which I can only say: eat your heart out, Mark Knopfler. I still don’t think I shall be rushing out to any more guitar concerts, or buying any CDs, but I will admit that this concert revealed a wider range of possibilities than I had dreamed possible.

The photographs marked ** were sourced online. Thanks to John who provided all the others.