Firestar

28 November 2017

John (never one to miss the opportunity for a bit of teasing) is fond of conjuring an image of me reading two books at once, one in each hand; not to mention reading two or three books in a day. As with all his teases, these have just enough truth in them to sting. I do not, of course, literally read two books at once. I never heard of anyone who could. But I often have four or five books on the go, so to speak, which I pick up, read and put down as the mood takes me. Just at the moment, for instance, I have been re-reading Jessie Burton’s The Muse (which Georgina lent me), Dickens’ Bleak House, Nick Harkaway’s Angelmaker and… well, we will come back to the other in a moment.

I have always been a voracious reader, and I might just conceivably read two books in a day. But they would have to be pretty short, and I would have to be unusually focused. These days I more often do my reading in short bursts. I’m not sure whether this is due to competing distractions, or to physical constraints. Despite wearing varifocals, I usually remove my spectacles when I am reading, and maybe my unconscious mind is placing a limit on the detailed work that I give to my unequal-strength eyes.

It is true, though, that I am a fast reader. Speed-reading can be trained; for me it comes naturally, but at a price. I often skim, rather than read, and skimming means missing things. So I can, and do, get renewed pleasure from reading books a second or third time. Georgina finds this puzzling, I think. She likes to read a book once and move on to the next, which is probably why there are a lot more books in my house than hers. When she has read a book once, she is quite likely to give it away. I cling on to my books avariciously, just in case I ever want to read them again.

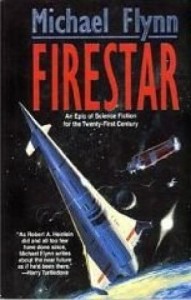

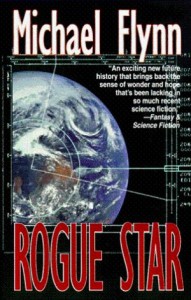

Which brings us to Firestar, the first in a series of four long novels by the American science-fiction author Michael Flynn. The others (in sequence) are Rogue Star, Lodestar and Falling Stars. Firestar was published in 1996 and the others over the next five years. My copies are imports; so far as I can tell they were never published in the UK, or probably therefore in Australia. So you are unlikely to have heard of them. I first read them perhaps ten or so years ago, and for a second time over the last few weeks.

The books are set in what was then the near future, and concern the (re)conquest of near-Earth space, led not by governments but by a wealthy megacorporation and its visionary chairman and co-owner, Mariesa van Huyten. The science part of the fiction is hardcore, detailed and – so far as I can tell – entirely plausible. To give a flavour: one of Flynn’s fictional scientists develops a room-temperature superconductor. No such thing exists in the real world; it is one of the Holy Grails of modern physics. In Firestar’s world a spacecraft is then constructed which uses the thrust of the solar wind against ship-mounted superconductor loops. I had never heard of such a thing, but the concept is perfectly valid: see the Wikipedia entry for “magnetic sail.”

The books are set in what was then the near future, and concern the (re)conquest of near-Earth space, led not by governments but by a wealthy megacorporation and its visionary chairman and co-owner, Mariesa van Huyten. The science part of the fiction is hardcore, detailed and – so far as I can tell – entirely plausible. To give a flavour: one of Flynn’s fictional scientists develops a room-temperature superconductor. No such thing exists in the real world; it is one of the Holy Grails of modern physics. In Firestar’s world a spacecraft is then constructed which uses the thrust of the solar wind against ship-mounted superconductor loops. I had never heard of such a thing, but the concept is perfectly valid: see the Wikipedia entry for “magnetic sail.”

Occasionally Flynn tries a little too hard. I found this most of a problem in the third book, Lodestar, in passages dealing with computer security. Bearing in mind that Lodestar was published in 2000, Flynn’s vision of the opportunities and dangers created by the internet is both vivid and prescient. But there is rather too much of his imagined computer-speak. Granted that computer geeks do often talk what sounds like gibberish to the uninitiated, Flynn has justification for writing this way; but whether real or imagined, it is still tedious.

Occasionally Flynn tries a little too hard. I found this most of a problem in the third book, Lodestar, in passages dealing with computer security. Bearing in mind that Lodestar was published in 2000, Flynn’s vision of the opportunities and dangers created by the internet is both vivid and prescient. But there is rather too much of his imagined computer-speak. Granted that computer geeks do often talk what sounds like gibberish to the uninitiated, Flynn has justification for writing this way; but whether real or imagined, it is still tedious.

Of course too much science would be a bad thing. Firestar and its sequels are novels, not a scientific treatise. Flynn gets this just about right.  There is enough hard (ie solid) science here to make his story feel grounded and plausible, but not so much as to lose his readers. And the books contain a good deal else. Over the course of 3,500 pages or so we get triumph and tragedy, science, adventure, politics, intrigue, family drama, social criticism and a bit of war. We also get a lot of ideas about the direction of American society, a handful of moral dilemmas and a parade of interesting, well-differentiated characters, far more fully developed than the stock figures of most science fiction.

There is enough hard (ie solid) science here to make his story feel grounded and plausible, but not so much as to lose his readers. And the books contain a good deal else. Over the course of 3,500 pages or so we get triumph and tragedy, science, adventure, politics, intrigue, family drama, social criticism and a bit of war. We also get a lot of ideas about the direction of American society, a handful of moral dilemmas and a parade of interesting, well-differentiated characters, far more fully developed than the stock figures of most science fiction.

Flynn handles the series’ thirty-year timespan smoothly. A small core of characters carry through from the first book to the last.  Mariesa is the central figure, but even her role has diminished by the time we get to Falling Stars; control of her megacorporation has passed to the next generation. Other characters, introduced in Firestar, become more important in later books, not always in ways you might have expected. Many others appear only in one or two of the books.

Mariesa is the central figure, but even her role has diminished by the time we get to Falling Stars; control of her megacorporation has passed to the next generation. Other characters, introduced in Firestar, become more important in later books, not always in ways you might have expected. Many others appear only in one or two of the books.

I never felt that Flynn was simply pulling the characters’ strings, to make them do what he needed them to do regardless of plausibility or consistency. On the other hand, I am not sure we ever see them as fully rounded individuals. Flynn shows us only what is necessary for the sake of his story. Characters change and develop over time, but we see those changes in a series of snapshots, not while they are taking place. Only with Mariesa do we get a more or less uninterrupted timeline. There again, it is her obsession which drives the overarching plot; by the end of Falling Stars, we see how it has paid off.

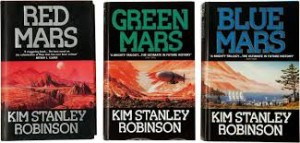

Also in 1996, another American author, Kim Stanley Robinson, published the last book in his Mars trilogy. The three books (which I have also read twice) make up an unquestioned classic, perhaps unique among all science fiction for receiving the accolade of a review in the Economist magazine. They also have their own Wikipedia entry (“Mars trilogy”) which is well worth a look. In them, Robinson sets out a vision of the colonisation of Mars, from the first colonists to a time when terraforming has generated a breathable atmosphere and a hydrosphere with real canals. He gives us much the same range of content as Flynn: well-grounded science, politics, character, revolution and war. Robinson’s is the grander vision, over a longer timescale; as a simple storyteller, Flynn perhaps has the edge.

And there is another difference. Robinson is a socialist, even I think by American standards. His vision is Utopian. He is very critical of big business and the transnational corporations, which he condemns for their amorality, short-termism and cynical manipulation of impotent governments. Flynn, on the other hand, is an unrepentant free-marketeer. He sees government as visionless when it is not actually corrupt, and admires the power of corporations to get things done.

And there is another difference. Robinson is a socialist, even I think by American standards. His vision is Utopian. He is very critical of big business and the transnational corporations, which he condemns for their amorality, short-termism and cynical manipulation of impotent governments. Flynn, on the other hand, is an unrepentant free-marketeer. He sees government as visionless when it is not actually corrupt, and admires the power of corporations to get things done.

When I first read Firestar I thought it may have been written, not just in emulation of the Mars trilogy, but in rebuttal. On rereading, I’m not so sure. Both authors are intelligent enough to admit that good may exist on both sides of a debate. And Flynn’s general world view is much more typical of writers of hard science fiction than Robinson’s. I still think the Mars trilogy was his model, but the element of rebuttal may be a by-product, not a purpose.

Just to be clear: Flynn believes in the power of the market, but what he admires most is ambition. A surprisingly large part of the first book, Firestar, is concerned with Mariesa’s takeover of a New Jersey school where the curriculum and teaching methods are completely overhauled to restore hope and vision which she believes have been lost. It’s not a back-to-basics prescription, but one which replaces process with purpose. Of course Mariesa has an ulterior motive for this involvement, but it is clear that it is Flynn’s own agenda she is pursuing. You may think, as I did, that this part of Firestar is Flynn’s own personal Utopianism, easy to describe but hard to achieve. A bit like his fictional science.

I feel more naturally drawn to Robinson’s point of view thn to Flynn’s, but it is hard not to be swept along by the conviction of Flynn’s narrative. And on one point I agree with them both: the necessity of returning to space, not just for the sake of science but for good hard utilitarian reasons. Their books are not just good stories, but tracts in favour of the exploitation of space, the ambition that is needed to take us there, and the benefits we may expect to accrue. Each series, after many travails, has an upbeat ending. We can only hope that the real world follows suit.

——————–

Firefly

21 November 2017

Firefly is, or perhaps was, a television science-fiction series created by Joss Whedon and first shown on American television in 2002. It was cancelled after only fourteen episodes had been made and eleven of them shown. Since then it has become a fan favourite, with all the trimmings: a DVD box set with all the episodes and “bonus features,” conventions, comic books and petitions for its return.

Firefly is, or perhaps was, a television science-fiction series created by Joss Whedon and first shown on American television in 2002. It was cancelled after only fourteen episodes had been made and eleven of them shown. Since then it has become a fan favourite, with all the trimmings: a DVD box set with all the episodes and “bonus features,” conventions, comic books and petitions for its return.

Some time ago Georgina lent me the box set (four DVDs), and last week I finally got round to watching them. I also enjoyed the audio commentaries, by Whedon and others in the cast or crew – you can choose to listen to them instead of the regular soundtrack. They aren’t very disciplined and contain a lot of pointless banter, but also a few nuggets about production and story which I would otherwise have missed.

The series’ central characters are a crew of independent traders and smugglers on board a Firefly-class spacecraft named Serenity. They ply for trade among the planets and moons of a single star system (not ours). The core planets of the system are high-tech environments, but the outer planets are frontier worlds, mostly deserts, with cultures approximating to the old American West. The show has been described as a “space Western,” an idea reinforced by the theme tune and much of the incidental music which have a strong country-and-western flavour. So we have spaceships, lasers and big explosions, but also horses, bandits and six-shooters.

The series’ central characters are a crew of independent traders and smugglers on board a Firefly-class spacecraft named Serenity. They ply for trade among the planets and moons of a single star system (not ours). The core planets of the system are high-tech environments, but the outer planets are frontier worlds, mostly deserts, with cultures approximating to the old American West. The show has been described as a “space Western,” an idea reinforced by the theme tune and much of the incidental music which have a strong country-and-western flavour. So we have spaceships, lasers and big explosions, but also horses, bandits and six-shooters.

It is a curious mix, and when I first watched an episode of Firefly on television some years ago I didn’t take to it at all, mainly, I think, for this reason. But in fact it’s not unreasonable to imagine that frontier worlds in some future interplanetary civilisation might be places where the dreamers and the desperate go to make their fortunes or a new start or simply to hide, and might be every bit as poverty-stricken and lawless as Firefly depicts.

Whedon makes good use of the opportunities provided by these two separate genre backgrounds. Some episodes are almost entirely one thing or the other: for instance the episodes Shindig and Jamestown are Westerns through and through, while the final episode, Objects in Space, is pure science fiction. Or perhaps not so pure. Its plot (and that of a couple of other episodes) depends on a chance meeting in interplanetary space which any hardcore science fiction fan will tell you is vanishingly improbable, given the vast distances involved and the velocities entailed by space travel. Other science fiction tropes are similarly deployed throughout the series when needed and ruthlessly discarded when they would get in the way.

Not that it matters. The whole premise of Whedon’s first great television hit, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, was complete nonsense. No-one cared. In fact a good deal more work clearly went into giving Firefly a consistent, believable background. The culture it depicts is a mixture of Western and East Asian, the idea being that this reflects the cultures of the star system’s original colonists. Chinese script and costumes recur regularly, and Chinese speech is occasionally used, especially for cursing. But Whedon sensibly decided that he would not allow plausibility of science or background to stand in the way of a good story. All his audience want is for his imagined world to be internally consistent (fans are notoriously picky about continuity errors) and to keep on throwing up challenges for their heroes.

Whedon has said that his original concept was for five seasons, each of 22 episodes. That would be almost unthinkable in modern British television, but is quite normal for American studios. So he had to think big. He needed interesting characters with room for development, challenging enemies for them to confront, and a story arc which would bind together otherwise stand-alone episodes. The binding had to be loose enough for the series not to become a serial, but strong enough for the show to have character and momentum.

To achieve all this required a consistent vision and direction, underpinned by good writing and performance. Buffy’s great success was due in part to razor-sharp scriptwriting with a blend of wit, irony, characterisation and self-awareness. Firefly doesn’t attain such heights, but the writing and especially the direction are still of good quality. The audio commentaries drew my attention to features in the direction and camerawork which, I now understand, help contribute to the interest and coherence of the show.

Whedon gave Serenity a crew of nine. That is another sign of his ambitions for Firefly: with nine major characters there would have been a lot of room for development. As it is, most of the nine have nicely sketched-in contrasting personalities with dominant traits, but they remain somewhat two-dimensional. All are competently acted. In a science-fiction or fantasy show it is essential to maintain the suspension of disbelief, and nothing will lose it faster than poor or uncommitted acting. That is not a problem here. We see more sides of the captain (played by Nathan Fillon, a Whedon regular) and the doctor (Sean Maher), but no doubt future episodes would have revealed more of the others.

Whedon gave Serenity a crew of nine. That is another sign of his ambitions for Firefly: with nine major characters there would have been a lot of room for development. As it is, most of the nine have nicely sketched-in contrasting personalities with dominant traits, but they remain somewhat two-dimensional. All are competently acted. In a science-fiction or fantasy show it is essential to maintain the suspension of disbelief, and nothing will lose it faster than poor or uncommitted acting. That is not a problem here. We see more sides of the captain (played by Nathan Fillon, a Whedon regular) and the doctor (Sean Maher), but no doubt future episodes would have revealed more of the others.

Ever since Buffy, Whedon has had a well-deserved reputation for featuring strong women in his shows, and Firefly is no different in this respect. Four of the nine principal characters are women, all of them different, none of them an adjunct or hanger-on. If I single out Jewel Straite, who plays the hippyish (but wholly competent) ship’s engineer Kaylee, it is only because she has such a gorgeous smile.

I also liked Christina Hendricks (later to become a regular in Mad Men) who appeared in two episodes as a diminutive, super-sexy but utterly untrustworthy con artist. The second time around, Firefly’s crew get the better of her, but the story leaves plenty of room for her to reappear in future episodes. One of the audio commentaries explains how Whedon deliberately includes hooks like this to allow for future development which will increase the show’s continuity and coherence if they are taken up, but will do no damage if they are not. Another sign of ambition and thinking ahead.

I also liked Christina Hendricks (later to become a regular in Mad Men) who appeared in two episodes as a diminutive, super-sexy but utterly untrustworthy con artist. The second time around, Firefly’s crew get the better of her, but the story leaves plenty of room for her to reappear in future episodes. One of the audio commentaries explains how Whedon deliberately includes hooks like this to allow for future development which will increase the show’s continuity and coherence if they are taken up, but will do no damage if they are not. Another sign of ambition and thinking ahead.

Among other antagonists, I particularly liked Richard Brooks who appears as a bounty hunter in Objects in Space; but as he ends the episode marooned in deep space, it seems less likely that he was expected ever to return. Alas, Firefly didn’t last long enough for us to see much of its major villains – the fascistic Alliance, bestial Reavers and sinister Men in Blue. Why have one Big Bad when you can have three? But there are clear hints that they might all have played stronger roles in future episodes which, sadly, we will now never see.

When first broadcast, Firefly’s audiences and ratings were mediocre, and in the cutthroat world of American television it’s easy to understand why the plug was pulled halfway through its first season. But I also think the cancellation was shortsighted. Buffy did not really get going until its second season, when its quirky premise was outweighed by critical appreciation and word-of-mouth endorsement among fans. Knowing this, you might think that television executives might have allowed time for Firefly’s audience base to grow in the same way.

But that’s all history. Firefly isn’t coming back; we must make do with what we already have. Joss Whedon has gone on to bigger (though not necessarily better) things as writer and, less often, director of a number of Hollywood movies, including several recent blockbusters. In 2012 he also made a movie of Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing, using black-and-white film, his own house as a set, and a cast of actors most of whom have been involved in one or more of his television shows. Don’t turn up your nose: it is as good an interpretation of the play as any, and better than most.

——————–

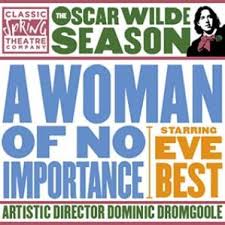

A Woman of No Importance

13 November 2017

John was staying with me most of last week – he arrived on Tuesday evening and went back to Manchester on Sunday. During his stay he visited seven different exhibitions which perhaps he will write about (hint, hint). I mostly had other things to do; but we did go together on Saturday evening to see a production of Oscar Wilde’s play A Woman of No Importance at the Vaudeville theatre in the West End.

John was staying with me most of last week – he arrived on Tuesday evening and went back to Manchester on Sunday. During his stay he visited seven different exhibitions which perhaps he will write about (hint, hint). I mostly had other things to do; but we did go together on Saturday evening to see a production of Oscar Wilde’s play A Woman of No Importance at the Vaudeville theatre in the West End.

We went partly because this is the one Wilde play which neither of us had seen, and partly because one of the leading roles is being taken by Eve Best.

She starred in a production of Eugene O’Neill’s play A Moon for the Misbegotten which we saw at the Old Vic ten years ago (I was astonished to find it was as long ago as that) in which she was simply sensational. We were hoping for more of the same.

A Woman of No Importance, though divided into the conventional four acts. has a curious dramatic structure. Not much happens for about an act and a half, during which the characters – mostly the idle rich – exchange witty Wildean epigrams in empty conversations. Then we realise that one of them, Mrs Arbuthnot, is a “fallen woman” who has brought up her son Gerald on her own after the boy’s father refused to marry her. Now the father, Lord Illingworth (whom she knew under a different name), has coincidentally reappeared on the scene and wants to employ the boy, whom he does not recognise, as his private secretary. The third and fourth acts include several scenes of considerable emotional intensity as this situation plays itself out, intercut with more witty vacuity among the other characters, who remain ignorant of the drama taking place among them.

Literary critics have generally regarded A Woman of No Importance as the weakest of Wilde’s plays. The discontinuity between artifice and drama is too great for them. It is (they say) as if two quite different plays had been spliced together. Michael Billington, usually an insightful critic, says in his Guardian review of this production: “The problem is that the play splits all too easily into two halves: sedentary chat and sentimental melodrama.”

That gives Wilde, one of the greatest playwrights of the last 200 years, a lot less credit than he is due. He surely knew quite well what he had done. The contrast between the idleness of upper-class lives and the double injustice done to Mrs Arbuthnot, by Lord Illingworth and then by society at large, is entirely intentional. Wilde had strong views about the hypocrisy of Victorian morals and the injustice done to women, not least by other women; and he was a satirist. So for the first act and a half we get fairly gentle mockery of the upper classes’ shallow lives, which sets them up nicely for the much fiercer satire which follows.

But the sudden change in tone does make demands. The end of the second act is indeed melodramatic, and there is a risk that the play will go off the rails: either because we don’t sympathise with Mrs Arbuthnot, or believe in her as a character; or because we fail to engage with Wilde’s critique of society, in which case the rest of the play will lack any point. In this production these hazards are avoided thanks to an outstanding turn by Eve Best as the “fallen woman.” We see how she has chafed under the judgement of an unjust society for twenty years without her spirit being broken. She wins our sympathy entirely, being defiant, passionate and just a little alarming. It is a performance and a role that would not be out of place in Ibsen or O’Neill. So much for sentimental melodrama.

But the sudden change in tone does make demands. The end of the second act is indeed melodramatic, and there is a risk that the play will go off the rails: either because we don’t sympathise with Mrs Arbuthnot, or believe in her as a character; or because we fail to engage with Wilde’s critique of society, in which case the rest of the play will lack any point. In this production these hazards are avoided thanks to an outstanding turn by Eve Best as the “fallen woman.” We see how she has chafed under the judgement of an unjust society for twenty years without her spirit being broken. She wins our sympathy entirely, being defiant, passionate and just a little alarming. It is a performance and a role that would not be out of place in Ibsen or O’Neill. So much for sentimental melodrama.

But this is not just a performance of broad brush strokes. When, half way through the second act, she realises who Lord Illingworth might be, you can see how her poise deserts her, in all kinds of little details: her fingers twitch, she clutches her handbag more tightly. The other characters, cocooned in their own little worlds, barely notice. But we know, or can guess, what is going to happen; and we can see that she fears it.

A strong central performance like this runs the risk that everyone else will be blown off stage. But in fact the main players are all good, and where they are weaker it is because Wilde made them so. In particular Dominic Rowan, as Lord Illingworth, makes an admirable foil for Eve Best; suave where she is passionate, cynical where she is earnest, selfish where she is loving; only similar in that they are both credible characters, not just constructions made to carry Wilde’s message or his wit. Illingworth is apparently the villain of the piece, yet he is given many of the smartest comebacks and wittiest lines. No doubt this is intentional. Society values his charm a lot more than it condemns his amorality; but we need to see the charm in order to point the satire, and Rowan shows us a devilish charm.

Among the rich and idle, Ann Reid stands out as a comfortable, well-meaning, ignorant widow and hostess. Eleanor Bron is equally good as a haughty matriarch who just knows she is always right and nags her husband incessantly (one of many small jokes running through the play, to keep us amused). If she hasn’t yet played Lady Bracknell, she should. Emma Fielding plays Mrs Allonby, who is a kind of female equivalent for Lord Illingworth, charming and amoral; they have some sparky exchanges in which Fielding holds her own, and she has a small but crucial role in the development of the plot, but her character fades from view when the drama begins.

Harry Lister Smith does a decent job as Gerald, star-struck by Lord Illingworth; he makes the most of his violent enthusiasms and sudden reversals. I was less convinced by Crystal Clarke as Hester Worsley, an American heiress whose naive earnestness is received with amused condescension. Whether Wilde meant her to be sympathetic or another butt for his satire, I don’t know, but it is a thankless and barely credible role in any case. Sam Cox as the nagged husband and William Gaunt as an elderly clergyman give two stock comedy turns; and Phoebe Fildes plays a young heiress whose every pronouncement seems to convey a satirical double meaning of which she herself is unaware (a bit more Wildean mischief, perhaps).

The production itself is fairly orthodox with a new naturalistic set for each act. While the curtain is down to cover the scene changes, Ann Reid and four of the cast come forward to deliver three Victorian songs, including Father’s a Drunkard and Mother is Dead. Their deadpan delivery adds to the humour. According to the programme, “Anne can frequently be seen performing her own highly successful cabaret show…” and if this is the kind of material she uses then the show is worth seeking out.

A Woman of No Importance is the first play in a season of Oscar Wilde plays planned for the Vaudeville Theatre in 2018. Production is by a new venture, the Classic Spring Theatre Company, whose artistic director is Dominic Dromgoole. The stated aim of the company is to bring new life, and presumably a new generation of audiences, to classic plays which were written for theatres with the traditional proscenium arch. This is an amusing reversal, given that Dromgoole’s most notable previous appointment was as Director of the Globe Theatre in London from 2005 to 2015, with its famous thrust stage.

There have been various attempts at creating new theatre companies in London under well-known artistic directors including Peter Hall, Kenneth Branagh and Jonathan Kent. None of them has lasted very long. Theatre is expensive to produce and rarely covers its costs without subsidy; the exceptions are cut-to-the-bone operations like the Orange Tree in Richmond, long-running successes and transfers from subsidised theatres which have paid off their set-up costs, and high-premium musicals like An American in Paris (see previous blog) which can get away with charging high prices. I applaud the ambition of Dromgoole and the Classic Spring company, but Wilde was a pretty safe choice for their first season – and even so the theatre was not full, on a Saturday night which is traditionally the heaviest booked of the week. Still, I wish them the best of luck. They have made a good start.

——————–

An American in Paris

13 November 2017

Last week Georgina and I went to see the stage production of An American in Paris which is currently running at the Dominion theatre in the West End. The show is based on the 1951 film starring Gene Kelly and Leslie Caron, but with some changes in detail. It has had some very good reviews, including five stars from the Guardian’s theatre critic Michael Billington who is not known for his generosity.

Last week Georgina and I went to see the stage production of An American in Paris which is currently running at the Dominion theatre in the West End. The show is based on the 1951 film starring Gene Kelly and Leslie Caron, but with some changes in detail. It has had some very good reviews, including five stars from the Guardian’s theatre critic Michael Billington who is not known for his generosity.

I have written previously that, with exceptions, I don’t much care for musicals. But there have been so many exceptions in the last year that I don’t think that is sustainable any longer. Rather, let me put it like this: I don’t care for musicals if I don’t think the music is any good. The music for An American in Paris is by Gershwin, so I thought I would be safe enough on that score.

I was also quite curious to see the show because two other musicals I have seen this year, the film La-La Land and the National Theatre’s production of Follies, both pay homage to the MGM musicals of the 1940s and 1950s. The final dream sequence of La-La Land is a direct reworking of ideas from An American in Paris; and Follies is a pastiche of the whole style. I enjoyed them both, and have written about them in earlier blogs.

The production premièred in Paris in December 2014, transferred to New York in 2015 and came to London in March this year. It has been a success everywhere it goes. The choreography is by Christopher Wheeldon and the stage design by Bob Crowley, both of whom have international reputations. With these credentials it looked like a pretty safe bet.

The production premièred in Paris in December 2014, transferred to New York in 2015 and came to London in March this year. It has been a success everywhere it goes. The choreography is by Christopher Wheeldon and the stage design by Bob Crowley, both of whom have international reputations. With these credentials it looked like a pretty safe bet.

And finally, Georgina likes musicals. Even if I was a bit bored, I thought she would enjoy the show.

So we went in with fair expectations… which, I’m sorry to say, were not quite fulfilled. At the end of the first half, we turned to each other and acknowledged that we were, sadly, underwhelmed. The second half was better and we came away happy, but in my case at least with a slight feeling of disappointment too. Granted, Follies has set the bar very high for stage musicals; but An American in Paris didn’t quite match up, and I couldn’t see where those five stars came from.

Don’t get me wrong. It wasn’t bad. The principals, Ashley Day and Daniela Norman, were very good, especially in the dance sequences. Indeed, the dancing generally was of a very high quality. She plays Lise Dassin, a ballet dancer on the brink of stardom, and much of the dance is ballet-influenced or pure ballet in character. He plays Jerry Mulligan, a young American fresh from World War II who has stayed in Paris to pursue his dreams of success as an artist, and falls in love with Lise.

Don’t get me wrong. It wasn’t bad. The principals, Ashley Day and Daniela Norman, were very good, especially in the dance sequences. Indeed, the dancing generally was of a very high quality. She plays Lise Dassin, a ballet dancer on the brink of stardom, and much of the dance is ballet-influenced or pure ballet in character. He plays Jerry Mulligan, a young American fresh from World War II who has stayed in Paris to pursue his dreams of success as an artist, and falls in love with Lise.

Daniela Norman was trained as a ballet dancer, and it showed. Her voice is not so strong, but she only had one shortish number to sing. She is in fact one of the alternates for the regular leading lady, Leanne Cope, who happened to be on holiday the week we went to the show; but neither Georgina nor I realised this until I happened to notice it on the Dominion website when I was preparing this blog.

Daniela Norman was trained as a ballet dancer, and it showed. Her voice is not so strong, but she only had one shortish number to sing. She is in fact one of the alternates for the regular leading lady, Leanne Cope, who happened to be on holiday the week we went to the show; but neither Georgina nor I realised this until I happened to notice it on the Dominion website when I was preparing this blog.

The role of Lise includes the show’s most demanding choreography, but Ashley Day as Jerry was put through his paces too. So far as I could tell he literally did not put a foot wrong. Perhaps he does not quite have the charisma of Gene Kelly; but that is an almost impossible standard, and a cruel comparison for any young performer.

The design was also pretty good. Unlike in Follies, which pays at least lip service to the classic unities of place and time, An American in Paris reflects its origins as a movie by darting all over the place, from a small café to a plush apartment, from the rehearsal rooms in a ballet theatre to the main stage as a performance takes place. The designer somehow has to conjure up all of these locations without cluttering the stage and getting in the way of the dancers. Very good use was made of projected backdrops, which according to the website use new techniques invisible to the audience, to conjure up Parisian scenes and images.

The design was also pretty good. Unlike in Follies, which pays at least lip service to the classic unities of place and time, An American in Paris reflects its origins as a movie by darting all over the place, from a small café to a plush apartment, from the rehearsal rooms in a ballet theatre to the main stage as a performance takes place. The designer somehow has to conjure up all of these locations without cluttering the stage and getting in the way of the dancers. Very good use was made of projected backdrops, which according to the website use new techniques invisible to the audience, to conjure up Parisian scenes and images.

I was particularly struck by what purported to be the designs created by Jerry Mulligan himself for Lise’s ballet: a few bold geometric shapes, in bright contrasting colours. They reminded me of abstract art I have seen somewhere – but though I have been racking my brain, and have searched through all my art books and a range of online resources, I haven’t been able to name the artist. Good for Bob Crowley, who has conjured up a plausible modernist style without descending into pastiche or blatant imitation.

If anything, the show’s weak point, unexpectedly, is the music. Gershwin’s original An American in Paris is a tone poem for orchestra, about twenty minutes long – not remotely enough to support the full length of a feature film or stage show. It is padded out here by the addition of several very familiar Gershwin songs including But Not For Me and I Got Rhythm, There is also, I believe, a small amount of music in the Gershwin style written by the film’s music director, Saul Chaplin.

If anything, the show’s weak point, unexpectedly, is the music. Gershwin’s original An American in Paris is a tone poem for orchestra, about twenty minutes long – not remotely enough to support the full length of a feature film or stage show. It is padded out here by the addition of several very familiar Gershwin songs including But Not For Me and I Got Rhythm, There is also, I believe, a small amount of music in the Gershwin style written by the film’s music director, Saul Chaplin.

But for all this there is quite a lot of repetition and a certain quality of sameness in the music. Some of the numbers also seemed to have been shoehorned into the show without contributing much to either narrative or character. The small orchestra directed by Stephen Ridley gave a taut, idiomatic performance and they earned their round of applause at the end. I just think that if the show had truly been through-composed by Gershwin, instead of being a compilation of his work, it would be a more satisfactory musical experience, with more contrast and better matching of music, character and story.

Still, this is scarcely enough to explain why we left the theatre feeling not quite satisfied with what we had just seen. Now I have had more time to think about it, I wonder whether we may have been reacting to the slick professionalism of it all. The choreography, the design, the performances – all were in place, but none of them conveyed much feeling. The odd thing is that the love story in An American in Paris is certainly stronger (if more predictable) than the paper-thin story of old loves in Follies, yet it is Follies which carried the stronger emotional weight.

Still, this is scarcely enough to explain why we left the theatre feeling not quite satisfied with what we had just seen. Now I have had more time to think about it, I wonder whether we may have been reacting to the slick professionalism of it all. The choreography, the design, the performances – all were in place, but none of them conveyed much feeling. The odd thing is that the love story in An American in Paris is certainly stronger (if more predictable) than the paper-thin story of old loves in Follies, yet it is Follies which carried the stronger emotional weight.

Perhaps this is just a consequence of the music in Follies being composed for the show, where in An American in Paris it has been adapted for the show. But it is also, I think, that Follies is a celebration, indeed a triple celebration: of the MGM musical style, of the inter-war Ziegfeld Follies shows, and of Stephen Sondheim himself, who is surely the world’s leading modern creator of musical theatre. An American in Paris is too remote from the film, and from Gershwin, to be a true celebration of either of them: rather, it uses them as props to justify itself. What it does, it does very well; but it feels just a little empty.

Five stars? No way. Four, perhaps.

By the way, some of the images in this blog are from the New York or Paris productions. Images from the London production are oddly hard to come by.

By the way, some of the images in this blog are from the New York or Paris productions. Images from the London production are oddly hard to come by.

——————–

William Boyd

12 November 2017

A couple of months ago I bought a copy of William Boyd’s 2009 novel Ordinary Thunderstorms from the big second-hand bookshop in Sedbergh. I knew Boyd’s name but could not remember having read any of his books. He is one of a generation of male authors, alongside Julian Barnes, Ian MacEwan and others, whose work is regularly praised by critics but which I have never felt impelled to read.

I knew that Boyd’s previous novel, Restless, had taken the form of a wartime spy story (actually it is a bit more than that, as I was to discover) and from the blurb on the back of Ordinary Thunderstorms I gathered that this was another literary thriller, though this time set among contemporary London’s underclass. The plot is more than enough to keep you reading; and you will probably also enjoy the swipes it takes at Big Pharma, or rather at the finance which stands behind it.

But the novel’s main virtues are the depiction of life among London’s down-and-outs and the vivid characterisation, some of it almost worthy of Dickens on one of his less extravagant days. Most engaging is the development of the protagonist, Adam, from someone to whom things happen into someone with real agency. This is not exactly an original idea – virtually all of Dick Francis’s heroes develop in a similar way – but here there is a moral dimension to Adam’s development. Towards the end of the book he does something at which his earlier self would be horrified, but you understand exactly how he got to that place, and most readers will probably be cheering him on. I know I was.

But the novel’s main virtues are the depiction of life among London’s down-and-outs and the vivid characterisation, some of it almost worthy of Dickens on one of his less extravagant days. Most engaging is the development of the protagonist, Adam, from someone to whom things happen into someone with real agency. This is not exactly an original idea – virtually all of Dick Francis’s heroes develop in a similar way – but here there is a moral dimension to Adam’s development. Towards the end of the book he does something at which his earlier self would be horrified, but you understand exactly how he got to that place, and most readers will probably be cheering him on. I know I was.

I enjoyed Ordinary Thunderstorms enough that I returned to Restless, a copy of which has been languishing on my bookshelves since soon after it was published in 2006. It won the Costa Book Award that year and was much promoted by booksellers. I probably fell victim to the hype but was then distracted by other reading. Perhaps also I was a bit discouraged by the setting: a major strand in Restless concerns spying in the Second World War, and I am not very fond of how that war seems to have infected so much of British consciousness ever since.

But Ordinary Thunderstorms had whetted my appetite and Restless, I was pleased to find, is just as good. The book alternates between the stories of Eva, a young Russian woman who is recruited after her brother’s death to work for the British secret service during the war, and of her daughter Ruth in the 1970s who gradually learns her mother’s secret history. Eventually the two narrative strands come together.

But Ordinary Thunderstorms had whetted my appetite and Restless, I was pleased to find, is just as good. The book alternates between the stories of Eva, a young Russian woman who is recruited after her brother’s death to work for the British secret service during the war, and of her daughter Ruth in the 1970s who gradually learns her mother’s secret history. Eventually the two narrative strands come together.

It is difficult to say more without giving too much away, but as in Ordinary Thunderstorms the book’s main pleasures are not in the story alone but in the characterisation and the setting. The descriptions of Eva’s training and of the work of British Security Co-ordination, whose covert task it was to win support for Britain in the United States in the period before Pearl Harbour, feel authentic. The details of Ruth’s present-day life have a mundane quality by comparison; she is living a slightly haphazard, undirected sort of life. I had some difficulty believing in parts of it which in any event petered out in a rather unsatisfactory way before the end of the book. But I liked her precocious little son Jochen, who has a distinctive, well-drawn character quite unusual for children in adult novels. (Don’t worry: nothing terrible happens to him. Another of my dislikes is novels which use child jeopardy for cheap thrills. Children, even fictional children, deserve more kindness. But I digress.)

Overall I think the plot of Ordinary Thunderstorms is tighter, with very little material included solely for colour; everything that happens is relevant. But the set-up for Restless is more interesting. Boyd claims that no previous novelist had written about British Security Co-ordination; I have no idea whether this is true, but it was certainly fresh to me.

As for themes, some are obvious (the war; differences between generations; secrets; poverty). But I think I detected an underlying idea about how we can be lulled into false security, drifting through life rather than making choices for ourselves. Eva learns to make choices; Ruth has drifted; Adam was drifting, but is shaken out of complacency.

Restless was Boyd’s tenth novel, but the first to be written in a genre mould. His first novel was A Good Man in Africa, which I have not read but is, I understand, a satire rather in the manner of Evelyn Waugh. His others are set against a wide range of backgrounds; he seems not to be one of those authors who, having found a successful formula, are content to repeat it. After Restless, I actively sought out a copy of his previous novel, Any Human Heart, which is a favourite of many online reviewers and seems to be his best-selling work. I finished reading it just a couple of days ago.

Any Human Heart is rather an unusual novel. It purports to be the journal of a fictitious British-cosmopolitan author, Logan Mountstuart, who was born in 1906, died at the age of 85, and who during his life rubbed shoulders with many of the century’s notable authors and a few other historical figures. It is episodic, inconsistent, unreliable but frank, sometimes funny and occasionally tragic. Mountstuart works as an art dealer and critic, an academic, a journalist and a spy. He starts rich and dies poor. He lives in London, Paris, New York, Nigeria and the Bahamas. Along the way he sees the Spanish civil war and the Biafran war at first hand, and gets peripherally involved with the Angry Brigade and Baader-Meinhof.

Any Human Heart is rather an unusual novel. It purports to be the journal of a fictitious British-cosmopolitan author, Logan Mountstuart, who was born in 1906, died at the age of 85, and who during his life rubbed shoulders with many of the century’s notable authors and a few other historical figures. It is episodic, inconsistent, unreliable but frank, sometimes funny and occasionally tragic. Mountstuart works as an art dealer and critic, an academic, a journalist and a spy. He starts rich and dies poor. He lives in London, Paris, New York, Nigeria and the Bahamas. Along the way he sees the Spanish civil war and the Biafran war at first hand, and gets peripherally involved with the Angry Brigade and Baader-Meinhof.

The book is undoubtedly a tour de force. Logan Mountstuart feels like a real person, and this like a real life. You see his golden promise turn to disillusion and decline. Every other figure in the book is peripheral, although there are some amusing vignettes and a measure of satire: Virginia Woolf comes out of it very badly, but I have no idea whether the incidents in which she features are based on real events or entirely out of Boyd’s imagination.

Mountstuart marries three times; all end badly. He also has many affairs, lusts after many more women, and writes about them. In fact quite a lot of the book is concerned with sex: not in an explicit way (mostly), but we see Mountstuart’s libido at work and how it affects his personality and his relationships. Perhaps this is to be expected in a private journal, but it did seem to me a bit excessive, not to say obsessive.

If the book has a theme it is the one which Boyd puts into Mountstuart’s words towards the end. “That’s all your life amounts to in the end: the aggregate of all the good luck and the bad luck you experience… There’s nothing you can do about it: nobody shares it out… it just happens.” And: “You must live the life you have been given.”

The thing is, I don’t altogether believe it. Obviously your life would be different if you were born very rich or very poor, or deaf or blind or lame, or the opposite sex, or any number of different things that Fate can hand out. But you can still choose how to play the hand you are given, with purpose and struggle or with meek acceptance. Of course it is possible that Boyd is writing in character, putting into Mountstuart’s words the thoughts of an old man who knows he hasn’t made the most of his life and is making excuses to himself for this.

I found the last few pages of Any Human Heart the most moving, as Mountstuart acknowledges to himself that he is coming to the end, when acceptance is all that is left. It is the same late-autumnal feeling that is evoked in Richard Strauss’s masterpiece, the Four Last Songs: a wistful melancholy rich in memory. Mountstuart is a memorable creation, and the development of his character from boyhood through to old age is convincingly portrayed. I don’t altogether agree with his philosophy; but this is still a very good book.

——————–

Ministry of Flat Walks 04 : Loughrigg Tarn

7 November 2017

To follow this walk, open another tab on your browser and go to this web address: http://bit.ly/2j6aTDL.

I have not been too lucky with the weather on my visits to the Lake District this year, but this last weekend, the first in November, has been a pleasant exception, and on Sunday morning the skies were bright and clear. John and I did not altogether trust that this would last, so we decided to set out early, while the going was good. We were still hoping to see some autumn colours, though many of the trees are already bare.

We decided to go to Loughrigg Tarn, another location which I remember from holidays when I was a boy. It is a fifty minute drive from Cark, and some of the world’s slowest drivers seemed to be out in their cars, much to John’s annoyance. But we were not really in a hurry; and it’s easy to forget that we are probably more familiar with the twisting, hilly roads than most other visitors.

Loughrigg Tarn lies in a hollow of the hills just north of Skelwith Bridge and the River Brathay which flows into the north end of Lake Windermere a couple of miles to the east. Unlike Tarn Hows, it is a natural feature. The tarn itself and much of the land around it are owned and maintained by the National Trust.

In fact I have a very specific memory of Loughrigg, because when I was a boy this is where we once found a splendid ancient tree which was no fewer than four trees in one. There was a single thick trunk, but another tree had grafted itself into one of the hollows of the V formed where the trunk divided; then this process had somehow repeated itself; and finally mistletoe had grown parasitically on to the tree. I remember the mistletoe, but not any of the other component trees, though I think that sycamore was probably one of them. Alas, there is no sign of it now; I suppose Father Time has swept it away. Somewhere in the family we have, or had, a black-and-white photograph of the tree, but for now neither John nor I can find it. Perhaps it will turn up some time when we are thinking of something else.

I remember the tree and the grassy meadow sloping down to the tarn, but not much else from those early visits with Mum and Dad. However, we have been occasional visitors ever since. I think that one of my favourite photographs in the family album, of Mum with a willow catkin sticking out of her favourite sheepskin bobble hat, was taken at Loughrigg.

I remember the tree and the grassy meadow sloping down to the tarn, but not much else from those early visits with Mum and Dad. However, we have been occasional visitors ever since. I think that one of my favourite photographs in the family album, of Mum with a willow catkin sticking out of her favourite sheepskin bobble hat, was taken at Loughrigg.

The walk around the tarn is pleasant and not very strenuous, though not entirely flat. There were quite a few people out walking on Sunday, but it is, for now, a less well known beauty spot than Tarn Hows, and more unspoiled. Depending on where you start from, and whether you take the short cut across the meadow (we didn’t), the whole walk should take about fifty minutes.

We parked our car in a muddy parking spot (room for several cars) just below the minor road junction south of the lake, and started our walk by following the Grasmere road northwards for about half a mile. There is no official car park, and though there are several off-road spaces which can be used for parking, this may be another location better avoided in high summer, at least if you want to park reasonably nearby.

From where we started, there is one quite steep, but also quite short, hill to be negotiated as you follow the Grasmere road northward. A dry stone wall separates you here from the meadow leading down to the tarn, but there are places where you can see over the wall and across the tarn. Fortunately the road was not very busy, though I believe it does get busier in summer, as for ordinary cars it is a useful way of bypassing the bottleneck at Ambleside if you are going to Grasmere or further north. That’s another reason for coming here in the off-season if you can.

After a while the dry stone wall gives way to a fence of a type I think characteristic of the Lake District and which is a strong feature in my early memories of Loughrigg: three- or four-bar iron railings and fence posts, rising to chest height, in long sections bolted together. In the railings is a gate opening on to the meadow and a path to the far side of the tarn. You can clearly see this path on the map. There was a rather loud group of ramblers just starting along the path when we reached it, prompting much grumbling from John: why do all these people come to enjoy the peace and quiet of the Lakes, and then pollute it with their noise? So we decided not to take this short cut and continued along the road until we reached a gate with various National Trust signs mounted on or near it, leading into the farm track which runs along the hillside above the north side of the tarn.

This is an excellent track for walking along as it is dead flat, with a good, level (though mostly unmetalled) surface, and several benches along the way where you can sit down to rest your feet and admire the view. Last time John and I came here we sat on one of these benches and ate our lunch in a cold drizzle. This time we had no lunch, but there was no drizzle either, and John took several photographs looking westwards into Langdale and towards the Pikes. Here is one of them.

It was a mistake not to bring lunch, as the walk was over all too quickly. We had not trusted the weather, but if we had spent a quarter of an hour longer at Cark I could have made a picnic lunch and a flask of tea for us to take with us.

It was a mistake not to bring lunch, as the walk was over all too quickly. We had not trusted the weather, but if we had spent a quarter of an hour longer at Cark I could have made a picnic lunch and a flask of tea for us to take with us.

Unfortunately, because of Loughrigg’s position tucked into a hollow of the hills, it is difficult to find any way of lengthening the tarn walk without including at least one quite steep hill – just look at the contour lines on the map. But there are several other good walks nearby which may eventually find their way into this series: for instance, along the bank of the Brathay from Skelwith Bridge to Elterwater and back, or around Grasmere and Rydal Water, both of which we have done in previous years. Perhaps next year.

As it was, we returned to Cark for lunch (two of Higginson’s excellent little quiches, one each) and then walked to Cartmel and back in the afternoon, stopping briefly at Cartmel Coffee for a pot of tea. The décor and the furniture have changed, the award certificates earned in previous years have disappeared; and the woman in puce coloured boots who used to be in charge was not there. Checking online this morning, I see there has been a change in management, which is a pity – but perhaps the new owners will be even better. The new furniture, at least, is nicer. Cartmel village was quite quiet, with no sign of the crowds which came for the bonfire on the previous evening. We are now into winter.

——————–

Holker Market and Cartmel Bonfire

6 November 2017

John and I have been up in Cark again this weekend. That’s only a fortnight after my previous visit, which is a bit sooner than usual, but there were two local events that I particularly did not want to miss.

The first was the Holker Winter Market. Just up the road from us – well, not quite a mile away – is Holker Hall, home of a branch of the Cavendish family who are major landowners in the area. The Hall is a proper stately home, though not on the scale of, say, Chatsworth or Woburn. It has extensive grounds and parkland, and is open to the public during the summer.

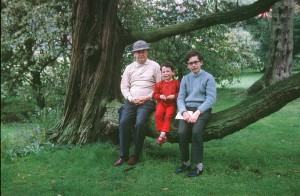

We visited Holker from time to time when I was still a boy. These two photographs, extracted from the family albums, must date from 1968 or 1969, when John was four or five years old; I am fairly sure they were taken in the Holker gardens. Yes, that’s John in the red. And notice that I am as usual carrying a book.

We visited Holker from time to time when I was still a boy. These two photographs, extracted from the family albums, must date from 1968 or 1969, when John was four or five years old; I am fairly sure they were taken in the Holker gardens. Yes, that’s John in the red. And notice that I am as usual carrying a book.

However, it is since John and I bought Stable Mews that we have become more frequent visitors. Various local events take place there each year and I should think that the Winter Market is probably the most successful: we were told that 2,500 people attended this Saturday and 3,000 this Sunday. We went on Saturday and found that the Market was larger than ever, but still had the same range of stalls and shows that we remembered from previous years.

It is an excellent place to buy Christmas presents. John bought a cushion for me there last year after I admired the design. There is a craft stall where all the goods have been made out of marble: John has two little carved elephants which I bought there for him a couple of years ago, and I have a marble toothmug. At a couple of stalls woodcrafts are on display which make excellent presents, except that I have bought so many now for different people that I am afraid of repeating myself. This year I admired a couple of beautifully shaped wooden bowls but resisted the temptation to buy; the truth is that I am running a bit short of shelf space to put my treasures. There was also a stall selling bobble hats. It was with some difficulty that I persuaded John not to take any pictures while I tried on a couple of them.

But the main glory is the local foods. There are cakes and biscuits, bread and cheese, smoked fish and meat, chocolate and fudge, jam and chutney. There are also various outdoor stalls if you want to eat and drink on the spot. We usually resist these, since home is so close by. I was tempted this year by the mulled wine, a treat for a chilly November day. However, John didn’t seem so keen and we resisted the temptation. In the end we went home with two jars of chutney, two jars of jam, some chocolate for Georgina and some fudge for ourselves, which was quite a moderate haul, I thought.

We had one disappointment: the Pudding Lady wasn’t there. I call her the Pudding Lady because that, or something very like it, was what her business was called. The first time we visited the Market, in the year we bought Stable Mews, she had a little stall and we bought two beautiful puddings from her. She told us she had a little kitchen at Water Yeat, on the west side of Coniston Lake and only four or five miles away from Woodgate (Mum and Dad’s holiday cottage). Since that first time I don’t think we have seen her again, and I suppose she must have ceased trading, which is a pity as the puddings were so good. Every time we drive through Water Yeat we wonder what has happened to her.

The second event was the bonfire and firework display at Cartmel. Last year, our first visit, John wrote a blog about it; but we had such a good time then that we thought we would go again. We both love fireworks and the bonfire is quite impressive too.

Fireworks always bring back memories of my boyhood. Each year for Guy Fawkes Night we would go up to Grandma and Grandpa’s house (that’s my Dad’s parents) in Banks near Southport, where we would have a bonfire and our own firework display. The house overlooked arable fields – West Lancashire is noted for its market gardens – so there were no livestock to disturb. Mum made treacle toffee in baking trays which was so hard that it had to be extracted with a chisel, and with edges sharp enough to cut if you weren’t careful. But it was the best I have ever eaten, with a dark treacly flavour that none of the commercial manufacturers seem able to reproduce.

Once I was old enough I was allowed out to help light the fireworks. Grandpa has a black metal tube less than an inch in diameter, but about three feet long, which we planted upright in the earth: it made an excellent launching pad for rockets. A wooden fence post not too close to the house served for catherine wheels. But my favourite was, and still is, the Roman candles which start with a gentle fountain of sparks but at irregular intervals shoot coloured stars high into the air. Rockets are great too, but they are over in a moment; Roman candles are more generous with their display.

In those days you were allowed to buy fireworks at age 13, and also to buy them loose (that is, not in selection boxes), so you could choose exactly what you wanted. I remember going into Fearenside’s newsagents at Childwall Fiveways the first year I was old enough and buying that year’s fireworks. It was a great thrill. I can even remember the names of the manufacturers: Standard (which I preferred), Brock’s, Paine’s, Wessex (which I always deemed slightly inferior). They mostly seemed to have been made in Huddersfield. All those firms have now disappeared and most or all of the fireworks sold in Britain are now imported from China. You can buy them all year round from specialist retailers, and fireworks to celebrate the New Year are quite common: you actually have to buy tickets for a riverside view of the Lord Mayor’s New Year fireworks in London, which are launched from a barge on the Thames not too far from Parliament where it all started.

Anyway, we drove up to Cartmel but parked a little way short of the village – last year we parked closer and after the event were trapped in our car for a long time before we could get home. As we walked into Cartmel there were more and more people assembling. I dislike dense crowds like this, and the darkness makes it worse; we didn’t quite hold hands, but we did make sure not to lose sight of each other. We made our way through the village to the racecourse (incidentally, part of the Holker estate) and stood on a bank, not too far from the bonfire, to watch. It was not as cold as last year, or perhaps we were better wrapped up. I’d estimate there was a crowd of a couple of thousand people and a sizeable sum must have been raised for local charities, which is the ostensible purpose of the event.

The best fireworks I have ever seen, bar none, were in Montreal of all places, when I visited the city one September in the 1990s. The city stages an annual fireworks festival and competition on the St Lawrence river, and I happened to be there for the finals, which the Chinese duly won. I remember that they had rockets which discharged a great spray of coloured stars, and those stars then each broke up into another smaller spray. I have never seen anything to match it and have wondered ever since how it was achieved. The fireworks at Cartmel weren’t quite so spectacular. But they were still pretty good.

Thanks to John for the photos of the Holker Market and the Cartmel fireworks