Quiz

15 December 2017

Beware : spoilers

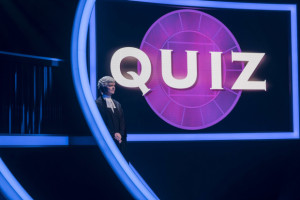

I went a few days ago to see a production of James Graham’s new play, Quiz, which is the last in this year’s Chichester Festival. Just now Graham is a wunderkind of the British theatre. He has two plays running in the West End, Ink and Labour of Love, and another, This House, currently on a national tour. I wrote about Ink on 16 July when it was still at the Almeida: its West End run is well deserved. This House, which is a play set in the Whips’ Offices of the major political parties during the 1970s (the time of the Lib-Lab Pact), was at the National Theatre in 2013 and I thought it the best play about politics I have ever seen. So I booked for Quiz without waiting for reviews, and as neither John nor Georgina seemed very interested I went on my own.

Quiz is based on a cause célèbre from 2001, when a certain Major Charles Ingram, a contestant on the hugely popular quiz show Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?, was accused of cheating. It was alleged that he used accomplices in the audience to endorse (or reject) his tentative answers by coughing at strategic moments. He, his wife and another man were eventually brought to trial and convicted of conspiracy to steal. They received very light sentences but of course Ingram had to resign his Army commission.

Quiz is based on a cause célèbre from 2001, when a certain Major Charles Ingram, a contestant on the hugely popular quiz show Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?, was accused of cheating. It was alleged that he used accomplices in the audience to endorse (or reject) his tentative answers by coughing at strategic moments. He, his wife and another man were eventually brought to trial and convicted of conspiracy to steal. They received very light sentences but of course Ingram had to resign his Army commission.

I enjoyed Quiz, but I do not think it is quite as good a play as Ink or This House. It is by turns funny, satirical, polemical, an examination of our love of quizzes, an exposé of the TV quiz show, a courtroom drama and a character study. I am not sure that the story can bear this much weight. In a programme note, Graham says that his main target is the unhealthy way in which our various public realms – politics, the media, the justice system and the police – are unhealthily entangled in ways that are often hidden from view. This is certainly a worthy subject. But in fact it only emerges for a few minutes in the second half of the show, when the Ingrams’ trial becomes a media circus and their lives are damaged in ways than go far beyond any due punishment.

The first half of the play offers a brief examination of the British love of quizzes and a potted history of television quiz shows, including pastiches of Take Your Pick, Bullseye and The Price is Right, with the versatile Keir Charles playing the roles successively of Des O’Connor, Jim Bowen and Leslie Crowther. The audience lapped it up. We also got a remarkably cynical look at the relationship on TV between quizzes and light entertainment, and a cruel portrayal of the television executive David Liddiment. I wonder if he has seen the show; it is not at all flattering.

Graham’s thesis is that most TV quizzes are not so much about general knowledge as they are about character. The contestants are exposed to public scrutiny, just as in modern reality television, of which these shows are thus a precursor. To get the best ratings requires sympathetic characters to do well. Graham suggests that TV executives caused the questions on Who Wants to Be….? to be more related to popular culture, so that “ordinary people” (ie the ITV demographic) could be seen to succeed. He also suggests that potential contestants are profiled in advance, and that questions are selected on the fly to be more or less within the individual contestant’s range of knowledge, depending on their audience appeal. I had never really thought about this; but it is horribly plausible.

In the second half of the play we see that Graham has not only shown us the inner workings of TV quizzes but tied them closely in to his plot. He suggests that Ingram and his wife had, in effect, broken the code. They wanted Ingram, in real life a rather staid, unimaginative man, to become a “character,” so that the producers would treat him kindly. So he apparently stumbles over successive questions, arriving at the right answer each time only after much hesitation. This of course looks suspect to the producers who suspect cheating in some form. The best role in the whole play is given to Sarah Woodward as Sonia Woodley QC, the Ingrams’ defence barrister, who (to my mind) demolishes the prosecution argument as a case of confirmation bias. The quiz’s producers couldn’t believe that this apparently limited Army major was about to walk off with their £1 million; therefore, he must be cheating; therefore the coughing conveyed messages; therefore it was all right to edit the tapes of the broadcast to draw attention to the coughing; it was also all right to ignore the fact that the Ingrams had never even met their alleged co-conspirator whose coughing it was. On this evidence (which I am sure is not all that emerged at the trial) the Ingrams were not criminals but victims.

It would be wrong to suggest that Graham’s purpose here is entirely polemical. Legal and media opinion remains divided on the case. Books have been written about it. What Graham does show is how a single set of facts are open to multiple interpretations and how the public at large can be, directly or indirectly, complicit in which interpretation prevails. He also shows the hidden forces at work: in this case, the television producers and executives who had a major stake in the continuing success of Who Wants to Be…?, since the show was franchised to the USA and many other countries, with royalties in the millions.

With all this substance to digest, it is easy to lose sight of the play. It was very well acted, directed and produced. The set is designed to suggest the studio for a television quiz show, but changes in lighting and a few props are used to conjure up other locations such as a pub, the Ingrams’ home or Liddiment’s office. Graham and the director, Daniel Evans, deserve credit for ensuring that the rapid flow of action (including different timeframes) never becomes confusing.

Most of the cast play multiple roles. I’ve mentioned Keir Charles’ quick-change act as a series of TV quiz show hosts, but his main role is as Chris Tarrant in a series of brief “clips” from Who Wants to Be…? This is caricature as much as anything; and of course TV personalities are often caricatured, so how can they object? Greg Haiste’s main role was as Paul Smith, the part-producer of the quiz, who (like Liddiment) is unlikely to feel his profile has been enhanced by the play: he is portrayed as the main persecutor of the Ingrams. Not nasty or malicious, but deeply cynical.

Where the play is perhaps a little lacking is in the exploration of character. Gavin Spokes gives an excellent performance as Charles Ingram, and you really feel his bewilderment as he is taken out of his comfort zone by the quiz’s demands. Whether you ultimately think him innocent or guilty depends partly on how you read his character, and this performance is nicely ambiguous. I did think, however, that the part of his wife Diana, played by Stephanie Street, was under-written. She gives a good answer to the question of why she likes quizzes: because, she says, she likes the certainty of knowing things in an uncertain world. But that’s more or less all we get. Other characters – family members and fellow quiz-lovers – are very lightly sketched in, and this leaves Ingram and his wife in a partial vacuum. There is a nice little flashback scene where we see how Ingram proposed to Diana, but this again tells us more about him than about her.

The play opens with a little quiz for the audience, and winners were announced at the start of the second half. (Not everyone was selected to participate; I was ignored.) I did not feel this served much purpose. I’ve learned, since seeing the play, that it is to have a West End run next year. That would be a good opportunity for a little editing to cut out the audience quiz, show us a bit more about Diana and the Ingrams’ world, and make a good play better still.

——————–

Films of the shows of the films

15 December 2017

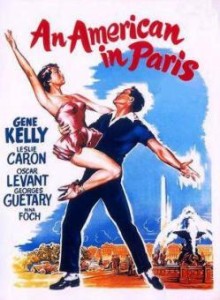

I wrote recently about An American in Paris, which Georgina and I saw at the Dominion theatre a few weeks ago. Afterwards she gave me a DVD of the film on which the show is based, and I have now watched that too.

I wrote recently about An American in Paris, which Georgina and I saw at the Dominion theatre a few weeks ago. Afterwards she gave me a DVD of the film on which the show is based, and I have now watched that too.

The relationship between show and movie is looser than I had imagined. The central love triangle is unchanged, but the music features a completely different selection from Gershwin’s work. Amazingly, though the story in the show is thin enough, I thought it even thinner in the movie. And I didn’t feel any more for the characters in the movie than in the show. In fact I found Jerry Mulligan, as played by Gene Kelly, rather annoying. The way he pursues Lise would these days be considered borderline harassment, and there is nothing to show her softening to him – she goes from shy and reticent to yielding and complaisant with no intermediate stages. On stage at least we saw Jerry wooing Lise with wit and gifts as well as persistence.

Part of the problem is that this is first and foremost a Gene Kelly film, and he gets the lion’s share of the camera’s attention. Leslie Caron built a Hollywood career out of her role as Lise: she is gamine and charming, but we scarcely see her dance at all until the lengthy final sequence. Kelly, on the other hand, gets three major numbers in which he sings and tap-dances to Gershwin numbers. The tap-dancing is sensationally good, but it screams “Look at me!” By contrast, on stage Jerry and Lise express their feelings in dance together. If they are showing off, it is to each other and not to the audience.

Part of the problem is that this is first and foremost a Gene Kelly film, and he gets the lion’s share of the camera’s attention. Leslie Caron built a Hollywood career out of her role as Lise: she is gamine and charming, but we scarcely see her dance at all until the lengthy final sequence. Kelly, on the other hand, gets three major numbers in which he sings and tap-dances to Gershwin numbers. The tap-dancing is sensationally good, but it screams “Look at me!” By contrast, on stage Jerry and Lise express their feelings in dance together. If they are showing off, it is to each other and not to the audience.

Some of my reaction to the film no doubt reflects changing tastes, as well as improvements in the style and techniques of film-making. An American in Paris begins with some classic shots of Paris in 1950 (notice the free-flowing traffic, scarcely believable today), but we are soon back in the studio, with flimsy sets and painted backdrops. Contrast this with, say, La-La Land, much of which – including the musical numbers – was clearly filmed on location. You do notice the difference. I thought the soundtrack a bit muddy too, and the image less than razor-sharp.

The film does at least make more of the character of the pianist, Adam, who opens the stage show. In the film he is played by Oscar Levant, an almost unknown name nowadays, who was once familiar to American audiences as a concert-standard pianist and comedian in Hollywood and a panellist on radio shows. We see him daydream of playing quite a long excerpt from Gershwin’s Piano Concerto, and the camera switches round to show that he is also conducting, playing the violins (all of them) and applauding wildly from the audience. Quite a dream! Levant’s performance on the piano is genuinely brilliant, even if it takes rather a long time to reach the punchline. The stage show wisely does not attempt to reproduce this sequence.

The film does at least make more of the character of the pianist, Adam, who opens the stage show. In the film he is played by Oscar Levant, an almost unknown name nowadays, who was once familiar to American audiences as a concert-standard pianist and comedian in Hollywood and a panellist on radio shows. We see him daydream of playing quite a long excerpt from Gershwin’s Piano Concerto, and the camera switches round to show that he is also conducting, playing the violins (all of them) and applauding wildly from the audience. Quite a dream! Levant’s performance on the piano is genuinely brilliant, even if it takes rather a long time to reach the punchline. The stage show wisely does not attempt to reproduce this sequence.

The history of the film is quite interesting too. It was directed by Vincente Minnelli and mostly completed by September 1950, at which point production was halted while Minnelli left to work on another movie. He returned six weeks later to film the concluding sequence, which is a stunning 17-minute ballet set to the music of Gershwin’s original concert piece, An American in Paris. Nothing like it had ever been attempted previously, and it has rarely been imitated since, though La-La Land does so and explicitly acknowledges the earlier film’s influence. The cinematography, revolutionary at the time, would nowadays be regarded as nothing special; but the art direction, with sets and costumes reflecting the work of French painters including Dufy, Renoir, Utrillo, Rousseau and Toulouse-Lautrec, is well beyond anything Hollywood would likely attempt today. There is an excellent appreciation of this final ballet sequence at http://bit.ly/2zRXt1H which is well worth a read.

The cinematography, revolutionary at the time, would nowadays be regarded as nothing special; but the art direction, with sets and costumes reflecting the work of French painters including Dufy, Renoir, Utrillo, Rousseau and Toulouse-Lautrec, is well beyond anything Hollywood would likely attempt today. There is an excellent appreciation of this final ballet sequence at http://bit.ly/2zRXt1H which is well worth a read.

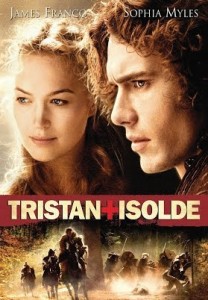

Georgina also lent me a DVD of a filmed version of Tristan and Isolde which I have just watched. Strictly, this is not a film of the stage show which we saw earlier this year at the Globe theatre (see blog on 23 June), nor is that show a remake of the film: rather, both are interpretations of a legend which goes back to Malory and earlier. The show and the film are about as different as they could be while still remaining true to the source material.

Georgina also lent me a DVD of a filmed version of Tristan and Isolde which I have just watched. Strictly, this is not a film of the stage show which we saw earlier this year at the Globe theatre (see blog on 23 June), nor is that show a remake of the film: rather, both are interpretations of a legend which goes back to Malory and earlier. The show and the film are about as different as they could be while still remaining true to the source material.

I’m afraid I didn’t like it at all, for a variety of reasons. Quite a lot of things happen in the film, including one big set-piece battle, two Irish raids, an ambush, a tournament, a siege, a secret tunnel, jealousy and treachery, as well as the love story. Despite all this it is curiously unexciting. I don’t think this is just that the story is too familiar: in any event, in this version it has been expanded considerably. But it has no rhythm. The central story is one of the great romantic tragedies, and it should have a cumulative impact as events rush to their doomed climax. Here I could feel no momentum.

Tristan, played by James Franco, fights heroically but is moody and dim. When he first meets Isolde and she claims to be a lady-in-waiting he somehow fails, despite numerous clues, to see through the deception. Isolde, played by Sophia Myles, is given far more agency than in traditional tellings of the legend – fair enough, in keeping with modern sensibilities. But she uses it only when it serves the purpose of the narrative. I could neither believe in nor sympathise with either of them, and that is deadly to the story.

Tristan, played by James Franco, fights heroically but is moody and dim. When he first meets Isolde and she claims to be a lady-in-waiting he somehow fails, despite numerous clues, to see through the deception. Isolde, played by Sophia Myles, is given far more agency than in traditional tellings of the legend – fair enough, in keeping with modern sensibilities. But she uses it only when it serves the purpose of the narrative. I could neither believe in nor sympathise with either of them, and that is deadly to the story.

The third character in the love triangle is King Marke, played by Rufus Sewell, who does his damnedest to be a sympathetic leader and cuckold. But he suffers even more than the other leads from jarring anachronism. He makes repeated attempts to unify the warring British tribes against the Irish, and to get them literally to sign a peace treaty; at one point he even unscrolls a parchment map. This tendency to muddle up the Dark Ages (when the story is set) and the Middle Ages persists throughout the film and is exacerbated by Anne Dudley’s music which has a persistent medieval lilt.

The third character in the love triangle is King Marke, played by Rufus Sewell, who does his damnedest to be a sympathetic leader and cuckold. But he suffers even more than the other leads from jarring anachronism. He makes repeated attempts to unify the warring British tribes against the Irish, and to get them literally to sign a peace treaty; at one point he even unscrolls a parchment map. This tendency to muddle up the Dark Ages (when the story is set) and the Middle Ages persists throughout the film and is exacerbated by Anne Dudley’s music which has a persistent medieval lilt.

Other improbabilities mar the film. The Irish champion Morholt taints his weapon with poison from the puffer fish, which is unknown in British waters. That was just careless: fungal and vegetable poisons abound, if one needed to be named at all. Tristan twice crosses the Irish Sea, alone: the first time, believed dead (but in fact half-dead) in a funeral barge; the second time in a tiny boat with remarkably modern-looking oars and rigging. No thought of currents or winds or tides. And James Franco’s elaborately coiffed hair-do is just ridiculous. Game of Thrones has shown how heroes can be heroic without recourse to the salon.

Other improbabilities mar the film. The Irish champion Morholt taints his weapon with poison from the puffer fish, which is unknown in British waters. That was just careless: fungal and vegetable poisons abound, if one needed to be named at all. Tristan twice crosses the Irish Sea, alone: the first time, believed dead (but in fact half-dead) in a funeral barge; the second time in a tiny boat with remarkably modern-looking oars and rigging. No thought of currents or winds or tides. And James Franco’s elaborately coiffed hair-do is just ridiculous. Game of Thrones has shown how heroes can be heroic without recourse to the salon.

There is one missing element and I fear that it too is crucial. In the original legend, and in most subsequent retellings, Tristan and Isolde unwittingly consume a love potion which overwhelms all responsibility and honour. Perhaps the writers and director wanted the film to be a straight quasi-historical drama (though that is belied by the many anachronisms) without supernatural elements. But the potion is an essential part of the tragedy: Tristan and Isolde have no free choice, and they betray Marke despite themselves. They are victims as much as he is. Without the potion they are scarcely better than Melot and Wictred who betray them to Marke.

Many years ago, Mum watched (on television) a Hollywood version of one of Jane Austen’s novels. It departed so far from the original in content, style and mood that she declared it to be a “travesty” and refused to watch to the end. There is lots of cinematic potential in the Tristan story, but it needs coherence, believable and sympathetic characters, and sufficient attention to detail to permit suspension of disbelief. This film achieves none of that. It is a travesty.

Many years ago, Mum watched (on television) a Hollywood version of one of Jane Austen’s novels. It departed so far from the original in content, style and mood that she declared it to be a “travesty” and refused to watch to the end. There is lots of cinematic potential in the Tristan story, but it needs coherence, believable and sympathetic characters, and sufficient attention to detail to permit suspension of disbelief. This film achieves none of that. It is a travesty.

——————–

Games weekend

5 December 2017

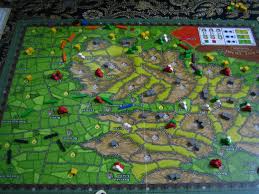

Three of my friends – David, Mark and Trevor – and I have just spent the weekend in Cark playing board games. I can come to Cark whenever I wish, and in fact do so about once a month. But for the others it was a break from routine and an opportunity to indulge our hobby in a beautiful part of the country where the food and beer are good. David comes from London, Trevor from Brighton and Mark from Bath, so it was a long drive for them all. Trevor had an unexpected duty at work and could not join us until Saturday lunchtime; the others had arrived on Friday.

The first game we played, on Friday afternoon, was Last Train to Wensleydale. Numerous board games have been made with a railways theme, but this one has a unique twist. Players represent 19th century entrepreneurs who construct branch railways leading into the Yorkshire Dales and the North Pennines, make a quick profit and sell out to the major rail companies before maintenance costs take hold. (This is more or less the historical reality.) In the process they have to use local influence to overcome the objections of suspicious landlords. Players take turns to bid for influence, construct track, lease locomotives, carry goods and passengers to the main lines, and sell out. It’s quite a tight and competitive game, as the map quickly becomes congested and profits are hard to come by. Mark won this one and I came third; no complaints, as I had been planning too far ahead and overlooked the cardinal necessity of leasing enough train capacity from the start of the game.

I cooked dinner for us on Friday evening but by the time that was over we were all too tired to play any more. So we started again the next morning. Our second game was Tempus, quite an old design with another familiar theme, the growth and development of a civilisation, from tribe to empire. Games of this type are frequently long and complex, but Tempus deliberately boils gameplay down to essentials. A map is built out of hexagonal tiles, so no two games are quite the same. Players start with three tokens on the map and gradually grow their populations, move across the map, conduct research, build cities and sometimes fight one another. The winner is the player who has the best cities and the most other tokens on the board at the end. The rules are contrived so that players who are lagging behind on one turn can catch up quite quickly, and our game was close throughout. But Mark won this one as well, despite having never played the game before: his cities were not as good as mine, but he occupied far more of the map with his other tokens. Sometimes there is quite a lot of combat in Tempus but on this occasion there was almost none. We don’t often play games in which there is direct conflict; as a result I think David and I were lulled into allowing Mark to get away with too much.

Trevor arrived at lunchtime and after lunch we played our third game: Russian Railroads. Despite its title, the railway flavour is slight. RR is a good example of the worker placement style of game, in which each player has a certain number of pawns, representing workers, and competes for opportunities to deploy those workers on a central board. When deployed they allow the player to take a specific action and deprive opponents of the chance to do so. I like this game because, more than any other that we play, it rewards you for having a consistent strategy which you follow through the game with as few distractions as possible. Most of our other games are much more tactical, requiring their players to devise rapid responses to constantly changing positions. I won this one by concentrating on industrial development until it would go no further, then switching to minor development of other options which gave good bonuses towards the end of the game. Trevor, who has won two of our previous three games of RR with a well-proven strategy, on this occasion tried something new which was a lot less successful.

Trevor arrived at lunchtime and after lunch we played our third game: Russian Railroads. Despite its title, the railway flavour is slight. RR is a good example of the worker placement style of game, in which each player has a certain number of pawns, representing workers, and competes for opportunities to deploy those workers on a central board. When deployed they allow the player to take a specific action and deprive opponents of the chance to do so. I like this game because, more than any other that we play, it rewards you for having a consistent strategy which you follow through the game with as few distractions as possible. Most of our other games are much more tactical, requiring their players to devise rapid responses to constantly changing positions. I won this one by concentrating on industrial development until it would go no further, then switching to minor development of other options which gave good bonuses towards the end of the game. Trevor, who has won two of our previous three games of RR with a well-proven strategy, on this occasion tried something new which was a lot less successful.

On Saturday evening we went for dinner to the Engine pub in Cark. The Engine has been a favourite ever since John and I bought Stable Mews, but it has recently had a change of management. The previous owners had I think been too ambitious, remaining open for long afternoons with little midweek custom; and I understand that they also had difficulty retaining staff, though I don’t know why. Anyway, John and I had heard murmurs that maybe the new regime was not up to the standard of the old.

On Saturday evening we went for dinner to the Engine pub in Cark. The Engine has been a favourite ever since John and I bought Stable Mews, but it has recently had a change of management. The previous owners had I think been too ambitious, remaining open for long afternoons with little midweek custom; and I understand that they also had difficulty retaining staff, though I don’t know why. Anyway, John and I had heard murmurs that maybe the new regime was not up to the standard of the old.

I needn’t have worried. It was just as well we had made a reservation, as the pub was busy and crowded. The beer was good and the food was excellent. We were asked five or six times – by the bar staff, someone whom I took to be the manager, and finally by the lady chef – whether we were happy, and were able to reassure them all. I had roast ham with sweet potatoes and sprouts with bacon, and will certainly have it again if given the chance.

After we returned home Mark decided he wanted an early night, but Trevor, David and I played another game: Metropolys. We’ve played this several times in the past and know it to be a shorter, simpler game. Nominally its theme is city building: the playing area is a map of an imaginary city divided into five districts, each of which contains ten separate neighbourhoods of five different types. Some neighbourhoods are seeded for bonus points. But the map might as well be an abstract design and there is nothing in the play to model actual city construction. The game consists of a series of structured auctions in which players compete to take control of the different neighbourhoods. Points are scored for achieving two different secret objectives and for having the best building in each district, as well as the various bonuses. I won this one as well, as I have done every time we have played, but on this occasion Trevor pressed me very close. It often happens that one of us discovers a good strategy for a game and the rest of us imitate it when we play that game again: gradually we learn, collectively, how to play better.

After we returned home Mark decided he wanted an early night, but Trevor, David and I played another game: Metropolys. We’ve played this several times in the past and know it to be a shorter, simpler game. Nominally its theme is city building: the playing area is a map of an imaginary city divided into five districts, each of which contains ten separate neighbourhoods of five different types. Some neighbourhoods are seeded for bonus points. But the map might as well be an abstract design and there is nothing in the play to model actual city construction. The game consists of a series of structured auctions in which players compete to take control of the different neighbourhoods. Points are scored for achieving two different secret objectives and for having the best building in each district, as well as the various bonuses. I won this one as well, as I have done every time we have played, but on this occasion Trevor pressed me very close. It often happens that one of us discovers a good strategy for a game and the rest of us imitate it when we play that game again: gradually we learn, collectively, how to play better.

On Sunday morning we played one more game, Canal Mania. The design of this game was inspired by the canal building boom in the nineteenth century which left England with a tangled network of canals. The game takes place on a map of England divided into hexagonal spaces and requires players, by acquiring and then deploying cards, to add tiles to the map, representing canals with locks, aqueducts and tunnels. CM is similar to several railway building games, but with the important difference that the canal routes are largely predetermined by contracts which the players acquire in the course of the game. Despite a few rough edges it is a good game, not too difficult and not requiring players to oppose each other directly.

On Sunday morning we played one more game, Canal Mania. The design of this game was inspired by the canal building boom in the nineteenth century which left England with a tangled network of canals. The game takes place on a map of England divided into hexagonal spaces and requires players, by acquiring and then deploying cards, to add tiles to the map, representing canals with locks, aqueducts and tunnels. CM is similar to several railway building games, but with the important difference that the canal routes are largely predetermined by contracts which the players acquire in the course of the game. Despite a few rough edges it is a good game, not too difficult and not requiring players to oppose each other directly.

I won this too, the first time I have won at CM, giving me a hat-trick for the weekend. Trevor ended without winning any of the games, but he usually wins his fair share on our regular games days, so he will be a bit disappointed but not dismayed. David also didn’t win any, though he came a close second in Canal Mania. He is a slower player than the rest of us but it doesn’t seem to do his results any good. In most of our games I tend to start quickly, slow down a bit when the position becomes more complex, then speed up at the end when it is just a matter of carrying a plan to completion, though I also look for any little tactical advantages that can be taken on the last few turns. Playing board games is a social activity and, without wishing to sound too pious about it, I don’t think taking a long time over your turns is very sociable. We all do it occasionally, when we are in a bind, but it’s a poor habit to develop.

When Canal Mania was finished we packed up quickly and went out for lunch to the Pheasant inn at Allithwaite, a couple of miles up the road towards Grange. John and I had never been there, but our neighbours Derek and Shirley had recommended it to me. They were right. We had an excellent meal, except that my roast potatoes had been back in the oven once too often and were tough. Trevor and David both had the special fish main course and pronounced it top class. For dessert I had a lemon posset, obviously homemade (it was served in a champagne flute glass), which was absolutely delicious. That is another recipe I shall have to learn.

When Canal Mania was finished we packed up quickly and went out for lunch to the Pheasant inn at Allithwaite, a couple of miles up the road towards Grange. John and I had never been there, but our neighbours Derek and Shirley had recommended it to me. They were right. We had an excellent meal, except that my roast potatoes had been back in the oven once too often and were tough. Trevor and David both had the special fish main course and pronounced it top class. For dessert I had a lemon posset, obviously homemade (it was served in a champagne flute glass), which was absolutely delicious. That is another recipe I shall have to learn.

After lunch we went our separate ways. A successful weekend; next year we shall have to do it again. We have plenty more games to try.