Time’s Witness

31 March 2018

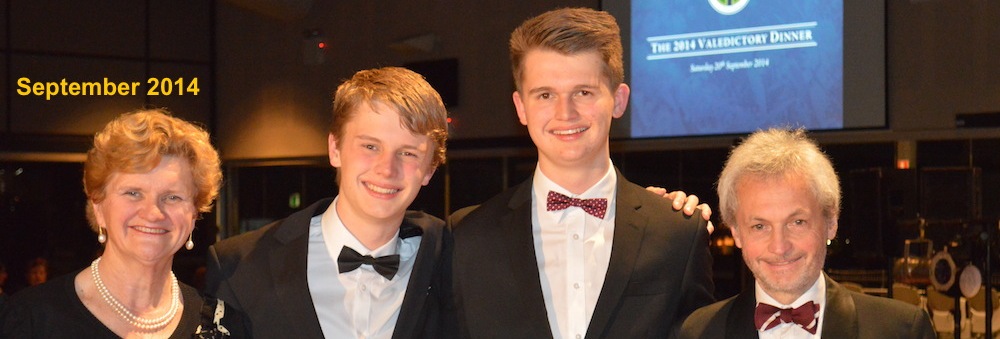

I came up north a few days ago. Usually I travel by train direct to Cark; but at Easter time the trains on the main line to Scotland tend to be uncomfortably crowded. So I came up to Manchester instead and stayed overnight with John before we drove up to Cark the following day. While I was with John I browsed through his bookshelves and found a book which I first read possibly as long as twenty years ago: Time’s Witness, by Michael Malone. I remembered the book and thought I would enjoy reading it again. So I did.

I came up north a few days ago. Usually I travel by train direct to Cark; but at Easter time the trains on the main line to Scotland tend to be uncomfortably crowded. So I came up to Manchester instead and stayed overnight with John before we drove up to Cark the following day. While I was with John I browsed through his bookshelves and found a book which I first read possibly as long as twenty years ago: Time’s Witness, by Michael Malone. I remembered the book and thought I would enjoy reading it again. So I did.

This was not, for me, unusual. The books which I like, I often read more than once. I don’t mean that when I reach the last page I immediately turn back to the beginning and start again. I have been known to do that, but only very occasionally. Most often I put the books back on the shelves and at some later time, when the mood takes me, take them down and read them again.

Why do I do this? I have never thought it particularly odd. I know for a fact that John does the same. I’m pretty sure that David does too, and Mum and Dad did in their time. It is at the very least a family habit. As for why, I get renewed pleasure from re-reading books that I like. And when I do I often notice fresh details that I had missed before. Some authors plan for this: they deliberately plant foreshadowings, often the slightest of hints, whose significance is not apparent on first reading but which pay off later. Dorothy Sayers (my favourite writer of detective stories) makes notably good use of this device. Only on re-reading do I notice, and gain added satisfaction from the subtle ironies and the author’s skill in placing them.

It was a surprise to me to discover that Georgina’s reading habits are quite different. When she has once read a book, she says, she rarely wants to read it again. She seems to be a slower reader than I am, but I suspect she takes in more of what she reads. So Georgina doesn’t (by her own account) own so many books as I do, My house is full of them: there are bookcases in every room except the bathrooms, and more books piled in corners where I hope they may be out of the way. I almost never throw books away (since very few are worthless) and it gives me almost physical pain to give them away to the charity shop even if I don’t expect ever to want to read them again.

But to return to Time’s Witness. The chances are that you have never heard either of the book or its American author. In fact it was Malone’s fifth novel, the second in what eventually became a series of three featuring chief of police Cuddy Mangum and his aristocratic sidekick Justin Savile V. The book was published in 1989, but afterwards Malone seems to have been sidetracked into American television, where he became a successful and much-lauded writer.

For a description of the book I do not think I can improve on this, taken from the back cover of John’s paperback (Abacus edition):

“Things have changed in Hillston, North Carolina… But the ghosts of the Old South sleep lightly. A young black man is on Death Row, racism and the invisible empire of the Klan are rearing their heads, and a dirty tricks campaign is mounting against the womanising candidate for state governor – who also happens to be the husband of Cuddy’s one true love.

To this political and racial intrigue… add what is certainly the best Southern trial scene since To Kill A Mockingbird….”

The blurb goes on to describe Malone as “one of today’s most outstanding crime writers,” but I think this misses the mark, and does Malone a good deal less than justice. I haven’t read all of his books, but from descriptions online it is clear that only the three in this series could plausibly be described as crime novels. And although the complex plot of Time’s Witness centres on a single killing of a corrupt white policeman by a victimised black man, that does not make Malone a crime writer any more than Greene or Dickens.

Time’s Witness examines issues of class and race, democracy and corruption, idealism and compromise, justice and punishment, the death penalty and individual conscience. It is also a doomed love story (though the participants do themselves no favours) and a vivid character portrait of two men: Cuddy Mangum, who rose from a blue-collar childhood through the power of education to be a sympathetic and credible liberal figure, and Isaac Rosethorn, the lawyer who was once Cuddy’s mentor, and who conducts the defence in the trial scene which occupies much of the second half of the book. Isaac’s handling of the defence is both deft and entertaining, but his set-piece speeches at the start and end of the trial make an eloquent case for racial equality and against the death penalty that is still resonant today.

Cuddy himself is the narrator here (though not in the other two books of the series), and Malone gives him a literate, sardonic voice. I wouldn’t describe Time’s Witness as laugh-out-loud funny, but Cuddy’s wit is often in evidence, both in narration and in dialogue. Other readers have described the book as a comedy, but if that is all they find in it they are missing the point.

More than anything, the book is a portrait of society high and low in the American South at a time of change, when voices like Cuddy’s are increasingly heard and old prejudices and divisions are being challenged. And the tone is ultimately optimistic. There is one irredeemable villain, perhaps necessary for the plot, and some of the other characters read like caricatures: the matriarch Edwina Sutherland, the journalist Bubba Percy, the priest Paul Madison. But the central characters are more complex, and believable. The liberal politician Andrew Brookside, a candidate for the State governorship whose womanising has made him vulnerable, has more than a bit of Kennedy about him; and among the other characters there may be resonances for American readers which pass over my head. Cuddy, though, is an Everyman; or at least the kind of honest, straight-talking, principled Everyman we might like to imagine ourselves to be. But Cuddy makes a fool of himself with Lee Brookside and it makes him more human.

I am tempted to write that it is a shame Malone has not written more than three books about Cuddy, Justin and Isaac. But in fact the third in the series, First Lady, which was written twelve years after Time’s Witness and which I also read much later, is a far more routine piece of work, a serial killer story lacking the scope and breadth of the earlier book. Rather than regret what might have been, we should be grateful for Time’s Witness: a timely reminder that, whatever we may read in the news, there are still liberal, humane voices to be found in America.

——————–

Ashes 2017-18 : where England went wrong

4 March 2018

England’s cricketers have at last reached the end of their tour of Australia. They won’t be coming home just yet: their one-day series in New Zealand is currently under way and they have a Test series against the same opponents still to come. But most England cricket fans will probably be feeling that, with the Ashes series comprehensively lost, the main business of the tour is over. Some of the cricketers are probably feeling the same way.

England’s cricketers have at last reached the end of their tour of Australia. They won’t be coming home just yet: their one-day series in New Zealand is currently under way and they have a Test series against the same opponents still to come. But most England cricket fans will probably be feeling that, with the Ashes series comprehensively lost, the main business of the tour is over. Some of the cricketers are probably feeling the same way.

Where did it all go wrong? The comments columns on the Guardian website have been full of answers, usually reflecting the bloggers’ long-held prejudices rather than informed observation. Perhaps that is inevitable in the immediate aftermath, which is why I have waited until now to set down my own thoughts.

First, we should give credit to the Australians, who turned out to be stronger opponents than we had expected, and who got most of their calls right. Starc, Cummins and Hazlewood are a formidable pace bowling trio. None of them is individually quite as ferocious as Mitchell Johnson on England’s last tour. And as a group I don’t think they quite match up to the great West Indians when Michael Holding or Malcolm Marshall or Curtly Ambrose were in their prime. But they are as good as anything since then, relentless and – crucially – fit. It is no coincidence that England managed to force a draw in the one match which Starc missed through injury.

First, we should give credit to the Australians, who turned out to be stronger opponents than we had expected, and who got most of their calls right. Starc, Cummins and Hazlewood are a formidable pace bowling trio. None of them is individually quite as ferocious as Mitchell Johnson on England’s last tour. And as a group I don’t think they quite match up to the great West Indians when Michael Holding or Malcolm Marshall or Curtly Ambrose were in their prime. But they are as good as anything since then, relentless and – crucially – fit. It is no coincidence that England managed to force a draw in the one match which Starc missed through injury.

England should have seen this coming, and probably did. But it is quite clear that they did not foresee how effective a foil Nathan Lyon would be for Australia’s fast men. None of England’s batsmen seemed to have any strategy for dealing with Lyon, and he was allowed to bowl long spells almost unchallenged while the fast men got their breath back. Lyon’s success should not have been a surprise. He has taken 290 Test wickets, including – unprecedented for an Australian spinner, let alone an off-spinner – 19 in four Tests on Australia’s tour of India in 2017. This was a major failure by England’s batsmen and, in particular, by the coaching staff. What else are they there for?

England should have seen this coming, and probably did. But it is quite clear that they did not foresee how effective a foil Nathan Lyon would be for Australia’s fast men. None of England’s batsmen seemed to have any strategy for dealing with Lyon, and he was allowed to bowl long spells almost unchallenged while the fast men got their breath back. Lyon’s success should not have been a surprise. He has taken 290 Test wickets, including – unprecedented for an Australian spinner, let alone an off-spinner – 19 in four Tests on Australia’s tour of India in 2017. This was a major failure by England’s batsmen and, in particular, by the coaching staff. What else are they there for?

The Australian batsmen also surpassed themselves, albeit against increasingly lacklustre bowling. Steve Smith was utterly dominant, plainly the best Test batsman anywhere in the world right now. But I refuse to believe that Usman Khawaja, or Shaun or Mitchell Marsh, are nearly as good as England allowed them to be. The selection of the Marsh brothers was a surprise, and controversial with Australian fans to begin with, but amply justified in the event. This was one of several good calls by the Australian selectors, which also included the recall of Tim Paine as wicket-keeper and the jettisoning of Peter Handscomb whose batting technique was quickly shown up by England. Only the inclusion of the untried Cameron Bancroft, ahead of the out-of-form but more solid Matt Renshaw, seemed questionable.

The Australian batsmen also surpassed themselves, albeit against increasingly lacklustre bowling. Steve Smith was utterly dominant, plainly the best Test batsman anywhere in the world right now. But I refuse to believe that Usman Khawaja, or Shaun or Mitchell Marsh, are nearly as good as England allowed them to be. The selection of the Marsh brothers was a surprise, and controversial with Australian fans to begin with, but amply justified in the event. This was one of several good calls by the Australian selectors, which also included the recall of Tim Paine as wicket-keeper and the jettisoning of Peter Handscomb whose batting technique was quickly shown up by England. Only the inclusion of the untried Cameron Bancroft, ahead of the out-of-form but more solid Matt Renshaw, seemed questionable.

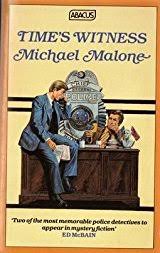

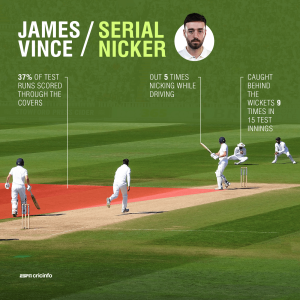

By contrast, England’s selectors plainly got several things wrong, not only with the wisdom of hindsight. They chose James Vince to bat at 3 despite all the evidence which shows that four times out of five he will give a catch to the slips or wicket-keeper, probably after making an elegant 20 or so. Never was a Test batsman so predictable. The selectors then compounded this error by choosing Gary Ballance as back-up. If you look only at Ballance’s Test match average he would seem a good first-choice selection, never mind a reserve. But if you look at the trajectory of his performances, from a bright start he has declined to mediocrity at best. His idiosyncratic method works against county bowling, but Test bowlers clearly have his measure. If (as has been suggested) he was selected at the direct insistence of Joe Root, it reflects badly on Root, coaches and selectors alike.

By contrast, England’s selectors plainly got several things wrong, not only with the wisdom of hindsight. They chose James Vince to bat at 3 despite all the evidence which shows that four times out of five he will give a catch to the slips or wicket-keeper, probably after making an elegant 20 or so. Never was a Test batsman so predictable. The selectors then compounded this error by choosing Gary Ballance as back-up. If you look only at Ballance’s Test match average he would seem a good first-choice selection, never mind a reserve. But if you look at the trajectory of his performances, from a bright start he has declined to mediocrity at best. His idiosyncratic method works against county bowling, but Test bowlers clearly have his measure. If (as has been suggested) he was selected at the direct insistence of Joe Root, it reflects badly on Root, coaches and selectors alike.

The absence of Ben Stokes had an impact on the whole tour: England not only missed his batting, bowling and fielding, but the balance and flexibility he brings to the team, not to mention his spirit and determination. The selectors could not have foreseen his absence or the reasons for it. But they should have recognised more of the implications. With Stokes in the team it was possible to imagine Bairstow batting higher up the order and ceding the wicket-keeping duties to Ben Foakes: Stokes and Moeen batting at 6 and 7 would have kept the team balanced. Without Stokes, Foakes became a fifth wheel. He could not be included without unacceptably weakening the side. There would have been less of a problem if Jos Buttler had been added to the party, either replacing Foakes or (if that was considered too harsh) alongside him. Buttler has a natural talent which is currently being wasted. His lack of recent first class matchplay should not have been held against him.

The absence of Ben Stokes had an impact on the whole tour: England not only missed his batting, bowling and fielding, but the balance and flexibility he brings to the team, not to mention his spirit and determination. The selectors could not have foreseen his absence or the reasons for it. But they should have recognised more of the implications. With Stokes in the team it was possible to imagine Bairstow batting higher up the order and ceding the wicket-keeping duties to Ben Foakes: Stokes and Moeen batting at 6 and 7 would have kept the team balanced. Without Stokes, Foakes became a fifth wheel. He could not be included without unacceptably weakening the side. There would have been less of a problem if Jos Buttler had been added to the party, either replacing Foakes or (if that was considered too harsh) alongside him. Buttler has a natural talent which is currently being wasted. His lack of recent first class matchplay should not have been held against him.

The selectors cannot be blamed for the rash of injuries which affected England’s back-up fast bowlers: Toby Roland-Jones, Jamie Overton, Mark Wood, Liam Plunkett and Steve Finn were all ruled out before the series started. TRJ, in particular, was a sad loss as his method, which relies on bounce rather than swing, would have been well suited to Australia. Jake Ball proved a disappointment and was dropped after the first Test, but I don’t think his inclusion was a mistake at the time. The other replacements, Tom Curran and Craig Overton, did as well as could be expected; they were lucky to be there, but Overton did well enough to suggest we may see more of him.

England’s greater problem was with the established bowlers. James Anderson bowled accurately and intelligently, and the Australians took no liberties against him, but he was rarely threatening. Stuart Broad was England’s best bowler on the disastrous 2013-14 tour, but he seems to have misplaced his mojo and was neither economical nor any kind of threat. It’s hard to say whether this dip in form will be temporary or permanent. When he’s on song he is unstoppable, but how long can we afford to wait? Chris Woakes was the most disappointing, though it is not clear that he was always fully fit. His pace was down and his ability to swing the ball was neutered by the conditions. I don’t think his place in the team is secure when Stokes returns.

Finally, no-one could have foreseen the total collapse in Moeen’s form and confidence, with both bat and ball. But the selectors should have realised that his bowling was vulnerable. For the last fifty years English off-spinners have struggled in Australia: the only exception has been Graeme Swann in 2010-11, bowling alongside a strong English pace attack against a troubled Australian batting line-up.

The back-up spinner on tour was the inexperienced Hampshire leg-spinner Mason Crane. In other circumstances this would have seemed a brave, forward-thinking selection, and Crane may well have a bright England future ahead of him. But if it was foreseeable that Moeen would struggle in Australia, then it was also foreseeable that an alternative might be needed, and Crane plainly is not yet ready.

England’s stocks of capable spin bowlers are not great, but it is not true that they had no alternatives. The best orthodox spinner in the country is Somerset’s Jack Leach (slow left-arm), who though he is still young has two full seasons’ experience in the county game, so is no novice. The decision to leave him at home now looks inexplicable.

The fact is, however, that even if England had been free of injuries and other distractions, and had chosen their best available team, they would probably still have lost. The matches might have been closer, but ultimately England had neither the firepower to trouble Australian batsmen in Australian conditions, nor the batting strength to resist Australia’s potent attack. Australia are on the rise, as they are currently showing on their tour of South Africa. Losing to them was no disgrace.

——————–

A new word

3 March 2018

The weather has been bad for the last week or so. We had blizzards (yes, really) on Tuesday and the snow has not shifted since then. It has also been fiercely, bitingly cold. So I have spent nearly all my time indoors, only venturing outside on Thursday and again this morning (Saturday) to lay in essential supplies, and scuttling home as soon as possible.

The weather has been bad for the last week or so. We had blizzards (yes, really) on Tuesday and the snow has not shifted since then. It has also been fiercely, bitingly cold. So I have spent nearly all my time indoors, only venturing outside on Thursday and again this morning (Saturday) to lay in essential supplies, and scuttling home as soon as possible.

To keep myself occupied I have been binge watching television series on the Amazon Prime video streaming service. This is quite unusual for me. I am much more likely to spend my time playing the piano or writing music, playing board or computer games, or reading. Watching TV is much more passive than most of my other occupations, so perhaps this bingeing is something to do with a general lack of energy brought on by the persistent cold I caught at Christmas and have not been able to shake off.

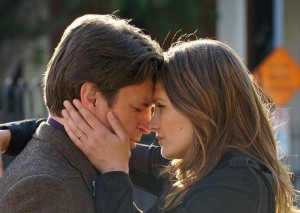

The series I have been watching for the last couple of weeks is Castle, a genre-hopping comedy-romance-crime drama based in New York. Richard Castle (played by Nathan Fillion) is a famous mystery novelist. He is brought in by the New York Police Department for questioning after a copy-cat murder is based on one of his novels. Castle is intrigued by Kate Beckett (played by Stana Katic), the detective assigned to the case, and decides to use her as the model for the main character of his next book series. He gets his friend the Mayor to pressure the police into allowing him to shadow Beckett as she goes about her job. Castle’s exuberant man-child personality clashes with the more reserved and professional Beckett, but the two eventually become friends and then lovers.

The series I have been watching for the last couple of weeks is Castle, a genre-hopping comedy-romance-crime drama based in New York. Richard Castle (played by Nathan Fillion) is a famous mystery novelist. He is brought in by the New York Police Department for questioning after a copy-cat murder is based on one of his novels. Castle is intrigued by Kate Beckett (played by Stana Katic), the detective assigned to the case, and decides to use her as the model for the main character of his next book series. He gets his friend the Mayor to pressure the police into allowing him to shadow Beckett as she goes about her job. Castle’s exuberant man-child personality clashes with the more reserved and professional Beckett, but the two eventually become friends and then lovers.

The show was immensely successful when first broadcast. It ran for eight seasons (2009-2016) and 176 episodes in the USA, but in the UK, so far as I can tell, it has been broadcast only on an obscure satellite network, and I had never heard of it. I stumbled over it rather by chance, as I scanned through the various TV shows offered by Amazon Prime. I thought it sounded fairly routine but also quite undemanding and good-natured. Checking out the online reviews I found this: “Castle proves that even a show with an unoriginal idea can be interesting and enjoyable if done well.” Good enough to be worth a look. And once I had seen the first episode I was hooked.

I’ve mentioned Fillion before, in my blog about Joss Whedon’s science fiction show Firefly (21 November 2017). That show had an ensemble cast, and in truth I did not think Fillion stood out among them; if anything I thought him a little one-note, though to be fair that may have been how his character was written, rather than any flaw in his acting. (I liked Firefly’s women better, but there may of course be other reasons for that.) In Castle, however, he gets the opportunity to project his charisma and charm, and really earns his top billing. As another critic has written: “[Fillion’s] real appeal comes from his ability to keep things light without winking at the audience. [He] plays characters with dangerous levels of charm, but they’re characters first of all.”

I’ve mentioned Fillion before, in my blog about Joss Whedon’s science fiction show Firefly (21 November 2017). That show had an ensemble cast, and in truth I did not think Fillion stood out among them; if anything I thought him a little one-note, though to be fair that may have been how his character was written, rather than any flaw in his acting. (I liked Firefly’s women better, but there may of course be other reasons for that.) In Castle, however, he gets the opportunity to project his charisma and charm, and really earns his top billing. As another critic has written: “[Fillion’s] real appeal comes from his ability to keep things light without winking at the audience. [He] plays characters with dangerous levels of charm, but they’re characters first of all.”

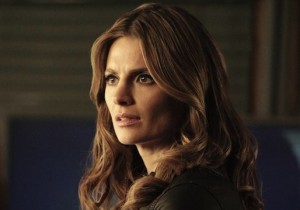

From time to time I have found Fillion’s character, Castle, a bit annoying – which is probably what the writers intend. He is far too smug. But I confess that my annoyance is tinged with jealousy, because his co-star Katic is absolutely gorgeous. A complete stunner. A parade of beautiful women feature as guest stars in almost every episode, but Katic outshines them all. It is completely implausible that such a glamorous woman should also be a successful homicide detective in a tough New York precinct, but who cares?

From time to time I have found Fillion’s character, Castle, a bit annoying – which is probably what the writers intend. He is far too smug. But I confess that my annoyance is tinged with jealousy, because his co-star Katic is absolutely gorgeous. A complete stunner. A parade of beautiful women feature as guest stars in almost every episode, but Katic outshines them all. It is completely implausible that such a glamorous woman should also be a successful homicide detective in a tough New York precinct, but who cares?

She isn’t just eye candy, but a capable actress, more than a match for Fillion. That same critic writes: “Katic’s cop is tough … but the actress suggests unspoken vulnerability and need.” I think the word I would use is brittle. It’s not the easiest of qualities to convey, but Katic gets it spot on. And as the series proceeds, we get to understand how Detective Kate Beckett came to be that way.

The basic format of Castle is the familiar murder-of-the-week, but this is underpinned by story and character arcs to keep the audience watching even through the more humdrum episodes. Apart from the developing romance between Castle and Beckett, there are two other main arcs: Beckett’s backstory, which unwinds through a string of episodes running from the first series to the seventh (I believe – I haven’t got that far yet), and Castle’s relationship with his teenage daughter Alexis, played by Molly Quinn, who is fifteen years old when we first meet her.  Quinn is herself just a year older than her character, which perhaps explains why she is so convincing: all the teenage traumas which the writers dream up for her (and which incidentally allow us to see another side of her father’s personality) might easily have been playing out in her real life or her contemporaries’. She doesn’t have Katic’s looks, but the show would not have the same emotional depth without her.

Quinn is herself just a year older than her character, which perhaps explains why she is so convincing: all the teenage traumas which the writers dream up for her (and which incidentally allow us to see another side of her father’s personality) might easily have been playing out in her real life or her contemporaries’. She doesn’t have Katic’s looks, but the show would not have the same emotional depth without her.

The show’s only real weakness is the crime stories around which each episode is constructed. It’s an intermittent weakness. Beckett’s backstory and the conspiracy which is gradually revealed to lie behind it have a realistically dark tone. Some of the other stand-alone stories are equally plausible and work well. The procedural detection offers plenty of twists and turns. But as the series has progressed, the writers’ striving to keep the stories fresh has become increasingly visible and intrusive. In this respect Castle reminds me of an older series, CSI New York, whose down-to-earth presentation of the business of detection was applied to stories that were often frankly bizarre.

But it doesn’t matter. Castle doesn’t strive to be realistic. It’s a fantasy, in the way of many crime series, like Elementary and Sherlock about which I wrote last year (13 March 2017), and distinct from, say, the novels of Graham Hurley or TV series like Homicide and The Wire. What we care about are the characters, and the great thing about a series of this length is that it allows room for them to develop in a natural way. You can guess that Castle and Beckett will eventually get together, but watching how they do so is still fun, especially with two such contrasting individuals. I have enjoyed seeing, too, how the writers have gradually allowed the characters’ qualities little by little to influence each other, so that Castle is no longer quite so superficial, nor Beckett quite so intense. They are in a few words good for each other, and it is oddly fulfilling to watch how they come to realise this.

But it doesn’t matter. Castle doesn’t strive to be realistic. It’s a fantasy, in the way of many crime series, like Elementary and Sherlock about which I wrote last year (13 March 2017), and distinct from, say, the novels of Graham Hurley or TV series like Homicide and The Wire. What we care about are the characters, and the great thing about a series of this length is that it allows room for them to develop in a natural way. You can guess that Castle and Beckett will eventually get together, but watching how they do so is still fun, especially with two such contrasting individuals. I have enjoyed seeing, too, how the writers have gradually allowed the characters’ qualities little by little to influence each other, so that Castle is no longer quite so superficial, nor Beckett quite so intense. They are in a few words good for each other, and it is oddly fulfilling to watch how they come to realise this.

Without much effort you can find various websites created by Castle fans, who quite clearly share the view that the Castle/Beckett romance is the show’s primary focus, not the murders and associated mayhem. There are lengthy articles detailing the tiny steps by which the relationship advances, carefully plotted by the showrunners to keep audiences engaged and anxious. Some bloggers suggest psychological reasons why these two (entirely fictional) characters have difficulty committing to each other despite their increasingly obvious feelings. Will they/won’t they is a very old trope, but it still works. And sustaining it for 80+ episodes before the couple do eventually get together is quite a feat.

Without much effort you can find various websites created by Castle fans, who quite clearly share the view that the Castle/Beckett romance is the show’s primary focus, not the murders and associated mayhem. There are lengthy articles detailing the tiny steps by which the relationship advances, carefully plotted by the showrunners to keep audiences engaged and anxious. Some bloggers suggest psychological reasons why these two (entirely fictional) characters have difficulty committing to each other despite their increasingly obvious feelings. Will they/won’t they is a very old trope, but it still works. And sustaining it for 80+ episodes before the couple do eventually get together is quite a feat.

It’s on the fansites that I came across a word, or rather a usage, which was new to me: shipping, derived (I think) from relationship, and used to mean endorsing a fictional romantic pairing, or wishing it would occur. The couple may be given a ship name which combines their two individual names. Thus Castle and Beckett become Caskett, which fits so well that I have been wondering whether the showrunners intended it that way from the outset, or whether it is just a happy accident.

It’s on the fansites that I came across a word, or rather a usage, which was new to me: shipping, derived (I think) from relationship, and used to mean endorsing a fictional romantic pairing, or wishing it would occur. The couple may be given a ship name which combines their two individual names. Thus Castle and Beckett become Caskett, which fits so well that I have been wondering whether the showrunners intended it that way from the outset, or whether it is just a happy accident.

I’m also a bit surprised to find myself among the ranks of the Caskett shippers. I know I have a romantic side, which expresses itself in music but otherwise is usually buried under layers of logic and practicality. It seems to have been unexpectedly evoked by the skill of Castle’s writers (and perhaps by my admiration for Stana Katic). Let no-one say that genre television is worthless or trivial if it can have such power.