JRPG

28 July 2018

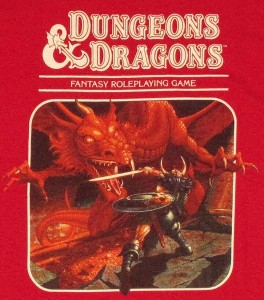

Any player of modern board or computer games should recognise the term RPG: Role Playing Game. Even if you don’t play, you may well recognise the name Dungeons & Dragons, arguably the first RPG ever published and certainly the most influential. The success of D&D spawned an entire genre that subsequently spread from niche board games to collectible card games, to computers, to online and multiplayer games like World of Warcraft. You have probably heard of that too.

In the original D&D one participant takes on the role of Dungeon Master while the other players represent individual characters. The DM creates an imaginary world or adopts one from many hundreds of published scenarios. The players respond to the challenges created by the DM, and roll dice to determine outcomes. Those challenges include puzzles and plots, clues and combat.

In the original D&D one participant takes on the role of Dungeon Master while the other players represent individual characters. The DM creates an imaginary world or adopts one from many hundreds of published scenarios. The players respond to the challenges created by the DM, and roll dice to determine outcomes. Those challenges include puzzles and plots, clues and combat.

A central feature of D&D is that the players group together as a party, each member of which has certain desirable qualities: one may be a skilled fighter, another a scout or thief, a third may be a healer, and so on. An unbalanced party, with (for example) all fighters but no healer, is likely to have a hard time of it. The need to work together as a group reinforces the social element of play.

Essentially the worlds of D&D are open-ended. The players decide where to go and what to do; the DM adapts and extends his world to respond to their choices. When RPGs made the leap to computers they had to be designed a little differently. Even today, it isn’t possible to programme a fully open-ended world, though the best games create worlds large enough that most players’ patience will be exhausted before they have explored all the possibilities.

CRPG designers also had to choose between giving the player a single character to control or a whole party. Either is possible. Most of the best CRPGs allow the player a whole party, but perhaps the best of them all, the Elder Scrolls series (Morrowind, Oblivion, Skyrim), use a single character. I shall be writing separately about them at some time in the future.

Virtually all computer RPGs contain a central story for the player to follow, though some are created with multiple endings, depending on the player’s actions and choices earlier in the game. But the story element is usually quite weak. Typically it involves a master villain seeking to conquer the world (think Sauron in Lord of the Rings), and the player’s actions throughout the game are ultimately aimed at building up their capabilities for the final confrontation. The larger games often also include sub-plots, but these are similarly weak, involving combat, delivery or collection of items or knowledge, or a combination of these. You don’t play the game for the story: the pleasure lies in exploration, acquisition of power, and combat.

Virtually all computer RPGs contain a central story for the player to follow, though some are created with multiple endings, depending on the player’s actions and choices earlier in the game. But the story element is usually quite weak. Typically it involves a master villain seeking to conquer the world (think Sauron in Lord of the Rings), and the player’s actions throughout the game are ultimately aimed at building up their capabilities for the final confrontation. The larger games often also include sub-plots, but these are similarly weak, involving combat, delivery or collection of items or knowledge, or a combination of these. You don’t play the game for the story: the pleasure lies in exploration, acquisition of power, and combat.

Most games also involve a collection of non-player characters (NPCs – another term derived ultimately from D&D) with whom the player interacts. But by and large these NPCs are no more than ciphers. Even if the script gives them motivations, they are largely devoid of personality.

CRPGs don’t need to be made like this. A trade-off is possible: more interesting stories, with more fully developed characters, but a less open-ended world, so the player is following a more closely defined script. Choices are still possible, in how the player develops the characters and manages combat, but it is not possible to stray far from the main storyline. This is a typical quality of RPGs made in Japan: JRPGs.

Not all JRPGs make it to the West. The story element means there is a lot of text to be translated into adequately idiomatic English. If text appears in the visuals (say, in street or shop signs, on banners or noticeboards) those have to be altered too. If there is speech, a whole new cast of voice actors have to be employed. For the game I have just been playing it is claimed that the full text amounts to something like 700,000 words, though you won’t get to read them all in any one playthrough.

That game is Trails in the Sky. It is the first in a series of three, all of which have now been localised for the Western market, and I expect that in due course I will get round to playing the other two, though it may be a while before I do: this one took 90 hours to complete, and the next is said to be twice as long. I needed something to occupy my time and distract me from the discomfort caused by my catheter (see previous blog), and Trails was largely successful in doing so.

That game is Trails in the Sky. It is the first in a series of three, all of which have now been localised for the Western market, and I expect that in due course I will get round to playing the other two, though it may be a while before I do: this one took 90 hours to complete, and the next is said to be twice as long. I needed something to occupy my time and distract me from the discomfort caused by my catheter (see previous blog), and Trails was largely successful in doing so.

My brother John doesn’t play computer games, but he is fond of Japanese manga books and anime films, and I imagine he would find quite a lot of the story elements in Trails very familiar. The game is story-heavy, featuring a conspiracy which is only gradually uncovered, and a series of reveals and reversals in character development. The characters are well drawn, both those in your own party (many of whom come and go throughout the game) and the NPCs. There is quite a lot of sly humour which has been well translated; time and effort was clearly spent on the localisation, and it shows. Your principal characters are teenagers and a romantic relationship between them gradually develops in the course of the game. There are also a couple of game long side-quests to pursue which involve collecting various items, some of which you have to go quite far out of your way to find. I had the advantage of a couple of game guides available online to help me, but even so I didn’t manage to complete all the side-quests, although I did finish the main storyline.

Trails has another peculiarly Japanese quality. Most RPGs involve monsters for you to fight. D&D, and most of its successors, adopted a Tolkien-like bestiary of goblins, ogres and dragons, with additions mostly drawn from other mythologies.

Trails has another peculiarly Japanese quality. Most RPGs involve monsters for you to fight. D&D, and most of its successors, adopted a Tolkien-like bestiary of goblins, ogres and dragons, with additions mostly drawn from other mythologies.

In JRPGs the monsters are bizarre, impossible creations: (clockwise from top left) a Boiled Egger, a Roly-Poly, a Giantfoot, a Halo Mole, among many others. The inhabitants of the world seem to regard these extraordinary beings with remarkable sangfroid, not to worry in the least about the peculiar ecology that produced them. I suspect John would find this element quite familiar too.

In JRPGs the monsters are bizarre, impossible creations: (clockwise from top left) a Boiled Egger, a Roly-Poly, a Giantfoot, a Halo Mole, among many others. The inhabitants of the world seem to regard these extraordinary beings with remarkable sangfroid, not to worry in the least about the peculiar ecology that produced them. I suspect John would find this element quite familiar too.

Trails isn’t the only JRPG I have played. The most well known of all JRPG series is Final Fantasy, now in its fifteenth iteration (each game is a stand-alone, not a sequel) and I have played two of them, FF7 and FF8. Both have similar qualities to Trails, particularly in their bestiary, their emphasis on story and their characterisation, including a range of teenage protagonists. The story of FF7, in which one sympathetic player character gives her life for the cause, is widely recognised among aficionados as one of the best ever created for a game. Unfortunately the FF series also features mini-games (that is, separate games embedded within the main game), some of which are excessively juvenile and tiresome: Trails is blessedly free of these.

One area where FF definitely has the edge is in the music. Not that Trails’ music is poor – far from it. You can hear it all at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AwxitM8L7Y0, but as that is nearly two hours’ worth I suggest you try numbers 22, 15 and 2, just to get a feel. However, FF’s music is so good that it is now earning a regular place in Classic FM’s annual Hall of Fame list, much to the disgust of more conservative listeners: see http://halloffame.classicfm.com/2015/chart/position/9/. Or if you prefer you can just listen to a selection of FF numbers (it is surely wrong to call them “songs” when mostly they do not feature voices at all): https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLED9329985AA3469E.

One area where FF definitely has the edge is in the music. Not that Trails’ music is poor – far from it. You can hear it all at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AwxitM8L7Y0, but as that is nearly two hours’ worth I suggest you try numbers 22, 15 and 2, just to get a feel. However, FF’s music is so good that it is now earning a regular place in Classic FM’s annual Hall of Fame list, much to the disgust of more conservative listeners: see http://halloffame.classicfm.com/2015/chart/position/9/. Or if you prefer you can just listen to a selection of FF numbers (it is surely wrong to call them “songs” when mostly they do not feature voices at all): https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLED9329985AA3469E.

I don’t really care about Classic FM or its Hall of Fame; but the level of recognition for this music is undeniable. Music for computer games serves a similar function to film music and is at least as challenging to create, possibly more so as it has to bear frequent repetition. Try playing these games in silence and it is quickly apparent that the composer’s contribution is every bit as great as the programmers’ or the artists’. It is odd, and perhaps a little sad, that these Japanese games use music clearly drawing on a Western tradition. Such is cultural imperialism. But its effectiveness in creating atmosphere is undeniable.

——————–

Catheter

28 July 2018

WARNING. This blog contains a certain amount of necessarily explicit medical detail. If you are nervous, squeamish or too imaginative for your own good, look away now.

John tried to persuade me not to publish anything on this subject at all. Once out there on the internet, it can never be reclaimed. But there is nothing here that I am ashamed of or want to keep hidden. If I do have any dark secrets (and I’m not saying), you won’t find them here, or anywhere online.

When I had radiotherapy for prostate cancer (see my blog on 10 February 2017), I was told that one of the possible side effects might be blood in the urine, and not to worry about it. So, a couple of months ago, when I noticed some mild bloodstains on the front of my underpants, I thought that was the most likely explanation. The stains appeared intermittently, about one day a week on average; I wasn’t leaking blood all the time. Nonetheless, as 18 months had passed since the radiotherapy, I didn’t think I should take anything for granted, and went to see my GP.

At Oxted Health Centre every patient has a regular GP for routine appointments, but if you ask for an urgent appointment you will see whoever happens to be on duty that day, and that is what I did. The GP did a quick dipstick test to check that I was not suffering from an infection and, when that proved not to be the case, referred me to East Surrey Hospital. Within a couple of days I received a letter inviting me for consultation with the urology team.

Unfortunately it was not the consultant (whom I know, and trust) that I saw, but one of his registrars. She told me that, though radiotherapy damage was the most likely explanation for my symptoms, they needed to rule out other possibilities such as kidney disease or bladder cancer. So I would be invited for a CT scan to check my kidneys, and for a flexible cystoscopy to look into my bladder.

The CT scan came first. I had expected something like the MRI scans which I have had previously, but a CT scan is different. An MRI scan builds a 3D image using magnetic scanning; a CT scan uses X-rays. For an MRI you are pushed into a long tube (a bit like the medical device in Star Trek) and have to lie still, possibly for half an hour (the longest I have had took 25 minutes) while the machine revolves around you. It’s pretty loud, unpleasant if you have claustrophobia, and can’t be used if you have metal implants. For a CT scan you similarly have to lie still, but the apparatus is just a loop, not a tube. Before the scan, the nurses injected an iodine dye into my bloodstream to help the CT images show up more clearly. I didn’t like that, but they seemed to think it was necessary. Anyway, after all that, the results were normal. I do not have a kidney disease.

So far so good. But the flexible cystoscopy was quite different. This involves pushing a small optical instrument up through the urethra into the bladder. Apparently the instrument is about the same diameter as a pencil, which seems pretty large to me; but plenty of patients have had this procedure without difficulty. It is performed under local anaesthetic only, which means that once the instrument gets inside, you may feel it. And unfortunately it caused me significant pain, enough that the surgeon abandoned the procedure and decided that I needed an optical urethrotomy to release the strictures (ie tightenings) which were causing an obstruction. These strictures might themselves have been caused by scar tissue following radiotherapy and might also be the cause of the bleeding.

I had the optical urethrotomy done on 9 July, in the short-stay surgery unit at Crawley Hospital, and came home the same day. As it was done under general anaesthetic, I was not trusted to make my own way home. A friend from Oxted collected me from Crawley, and Georgina came to stay overnight in case of emergencies.

I was returned home with a catheter: a narrow tube passing through the urethra into the bladder, where it is held in place by a small balloon. When first discharged from the hospital I was fitted with a leg bag, attached to the catheter through a valve, and was given a supply of night bags, one to be attached every evening when I went to bed and removed the following morning. But during the daytime, after the first day I had no bag attached, just the valve at the end of the catheter. I could use the lavatory in a more or less normal way by opening the valve.

My discharge notes from Crawley Hospital stated that the catheter would be removed, at East Surrey Hospital, five days later; they would send me an appointment. However, when the appointment letter arrived it was for a fortnight later. Instead of tolerating the catheter for five days I would have to do so for fourteen. I was not best pleased. I don’t know whether Crawley genuinely expected it to be five days, or whether that is the optimum (minimum?) time for the catheter to be used, or whether they knew it was unlikely to be achieved, but in any event I felt very let down.

And, just to be clear about this: wearing a catheter is unpleasant and uncomfortable. You can feel it pretty much all the time, both inside your body and alongside your leg where the catheter and valve are held in place. You need to drink a lot of water, not tea or coffee, juice or beer. You dare not stray too far from a lavatory because you experience sudden feelings of urgency. I was able to nip out to the shops, half an hour and back, but other than that I could barely leave the house. Most of the time I spent in my underclothes because wearing trousers added to the discomfort. Sitting down was worse: in order to sit at the computer I piled a folded-up blanket, two cushions and a towel on top of my usual chair. I was only ever really comfortable lying down at night.

What made it worse was that the urology registrar had warned me that there was a risk I might need to have a catheter permanently fitted, and/or to perform regular self-catheterisation, after this one was removed. I suppose you can get used to anything, and it is true that by the end of the fortnight the discomfort seemed a bit less (I had removed one of the cushions), but a permannt catheter was a horrible prospect.

And this all seemed like a gross escalation from my original complaint. No-one set out for me the balance of risks, as in: you can have this procedure which will enable us to see whether there is anything wrong inside your bladder, which there probably isn’t but it could be bad if there is, and there is a risk you may need a permanent catheter afterwards; or we can stop here, your symptoms may continue, and there is a small chance that we will fail to diagnose a serious disease or malignancy. I would probably have made the same choice, but no-one asked.

I had the catheter removed last Monday, 23rd July. That’s a very peculiar feeling: not painful exactly, but still horrible. The surgeon was now able to perform the flexible cystoscopy which had not been possible earlier, and I didn’t feel a thing. Indeed, I was able to watch the screen showing the inside of my own urethra and bladder. That’s a very odd experience. He found nothing untoward apart from a little redness caused by the catheter. Afterwards they kept me in the urology ward for a couple of hours, and made me drink lots of water so they could check I was able to empty my bladder properly without assistance. I did; I was; and I was discharged without any further need for catheterisation. I will have a follow-up appointment in five weeks or so, presumably to check that everything is still all right and to tell me what to do in case of any future problems. Perhaps they will also confirm what so far I have only inferred, that the original bleeding was caused by the strictures, which were probably caused by the radiotherapy. At last, I hope there will be nothing else.

So, subject to that further appointment, this story seems to have a happy ending. Fingers crossed. But I have had a very uncomfortable and anxious fortnight.

——————–

Macbeth at the NT

19 July 2018

A couple of weeks ago John, Janet, Chris and I went to see the National Theatre’s production of Macbeth, directed by Rufus Norris, starring Rory Kinnear and Anne-Marie Duff. Given the casting, this looked set to be a popular show, and I had booked early, before the reviews were in. When they appeared, they were not good: 2 stars out of 5 in the Guardian, 2/5 in the Telegraph, 3/5 in the Independent. Chris and Janet were anxious that they might have made the long journey down to London for no good purpose.

A couple of weeks ago John, Janet, Chris and I went to see the National Theatre’s production of Macbeth, directed by Rufus Norris, starring Rory Kinnear and Anne-Marie Duff. Given the casting, this looked set to be a popular show, and I had booked early, before the reviews were in. When they appeared, they were not good: 2 stars out of 5 in the Guardian, 2/5 in the Telegraph, 3/5 in the Independent. Chris and Janet were anxious that they might have made the long journey down to London for no good purpose.

We needn’t have worried. This was not a definitive Macbeth: could there be such a thing? It was heavily cut, though in this case (compare my preceding blog, about Maria Aberg’s Duchess) without compromising the plot or the poetry, and with a definite gain in momentum and intensity. And a creepily dark atmosphere was sustained throughout, reinforced by an all-black set dominated by an ominous, anonymous broad ramp: rotated, advanced and withdrawn by the Olivier Theatre’s stage machinery.

This was a grungy Macbeth. Dominic Cavendish, the Telegraph’s theatre critic, noted that “Duncan [here] seems to be presiding not so much over a kingdom as a localised turf-war.” A fair observation, but I didn’t feel that it mattered. Cavendish described the feel of the production as modern-day apocalyptic (perhaps he meant post-apocalyptic), and in that context who is to tell what is worth fighting for?

This was a grungy Macbeth. Dominic Cavendish, the Telegraph’s theatre critic, noted that “Duncan [here] seems to be presiding not so much over a kingdom as a localised turf-war.” A fair observation, but I didn’t feel that it mattered. Cavendish described the feel of the production as modern-day apocalyptic (perhaps he meant post-apocalyptic), and in that context who is to tell what is worth fighting for?

For all its Elizabethan trappings, Macbeth (like Othello, but unlike Lear) has always seemed to me to have a strong modern resonance, being concerned with power, ambition, cruelty and overreach. The problem for a modern-day interpretation of Macbeth is more practical. The witches trigger the Macbeths’ ambition, but witches in a modern setting can easily become absurd. That was a big problem in Rupert Goold’s version of the play for the RSC a few years ago, set somewhere approximating to WWII: he could make no sense of the witches, and even the incomparable Patrick Stewart as Macbeth couldn’t rescue the production.

But in a post-apocalyptic world, anything goes. You can combine modern dress with machetes, grunge with witchcraft. I am sure I detected traces of voodoo, which is another staple of post-apocalyptic fiction. And Norris had the good sense to curtail the witches’ scenes, so they retained impact but had no time to become ridiculous. No more hubble bubble, which anyway (according to the programme notes) may have been a later addition by Thomas Middleton. Perhaps the witches were Macbeth’s drug-induced nightmare? Apparently there were drug-taking references in the on-stage action, which somehow I completely missed.

Norris also curtailed the long, creepy scene in which Lady Macduff and her children are murdered. It’s a horrible scene which always makes me cringe and I was glad it wasn’t dragged out. And he contrived to omit the character of Dunalbane altogether, which I didn’t notice until afterwards. It can be difficult, sometimes, to tell Shakespeare’s courtiers and other minor characters apart; I can’t say that I cared.

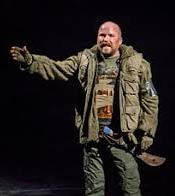

So much for the production; but it was the performances we had come to see. Rory Kinnear was not perhaps the most obvious choice for Macbeth, who is more often played as a tragic martial hero falling into temptation. Kinnear doesn’t really do heroic. He can be cool, or comic, or a tortured soul as in his paranoid Hamlet at the National a few years ago, which John and I admired. Anne Marie Duff is a terrific actress in almost any part: from Saint Joan at the National a decade ago (for which John has still not forgiven me, because he was not invited to my office theatre outing), to Berenice (Racine) at the Donmar in which she made a static play thrillingly alive. She looks like a natural for Lady Macbeth.

So much for the production; but it was the performances we had come to see. Rory Kinnear was not perhaps the most obvious choice for Macbeth, who is more often played as a tragic martial hero falling into temptation. Kinnear doesn’t really do heroic. He can be cool, or comic, or a tortured soul as in his paranoid Hamlet at the National a few years ago, which John and I admired. Anne Marie Duff is a terrific actress in almost any part: from Saint Joan at the National a decade ago (for which John has still not forgiven me, because he was not invited to my office theatre outing), to Berenice (Racine) at the Donmar in which she made a static play thrillingly alive. She looks like a natural for Lady Macbeth.

Unusually, we didn’t all agree about Kinnear. I thought he was pretty good, though it was not a conventional reading of the part. From the outset, Kinnear’s Macbeth is twitchy, paranoid, unpredictable. The witches don’t so much turn his head as tease out something that is already there. But in the final scenes, as the unlikely twin prophecies come to pass, he at last calms down and faces the oncoming doom unflinchingly; as if another part of him has known all along. I don’t think I have ever heard these lines better spoken:

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow,

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day,

To the last syllable of recorded time:

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

Macbeth as Hamlet. Very effective.

Anne-Marie Duff lived up to expectations, utterly convincing as the slightly brassy First Lady of this… mob. I particularly liked her controlled panic in the banquet scene, covering up for Macbeth when he starts seeing ghosts.  However she was not quite the dominating figure, whose ambition exceeds and fires her husband’s, that you get in some productions, and that I had expected from Duff; this was a more nuanced reading, and all the better for it. There is a danger that when Lady Macbeth disappears from the stage with half an hour to go, the rest can seem like an anti-climax, but that did not happen here. Rather, the loss of his wife is he first in the series of blows which destroy Macbeth.

However she was not quite the dominating figure, whose ambition exceeds and fires her husband’s, that you get in some productions, and that I had expected from Duff; this was a more nuanced reading, and all the better for it. There is a danger that when Lady Macbeth disappears from the stage with half an hour to go, the rest can seem like an anti-climax, but that did not happen here. Rather, the loss of his wife is he first in the series of blows which destroy Macbeth.

I cannot honestly say that the rest of the cast made much impression one way or another, except for the witches, and that was mostly for the gymnastics they were asked to perform. Banquo (Kevin Harvey), who can be a significant figure in the play, embodying the better side of Macbeth’s personality, the light against the dark of Lady Macbeth, was reduced in this production to a minor character alongside the others. Perhaps this weakened the impact of his murder, but it was consistent with the overall concept.

The other notable feature of the production was the soundscape. The music was by Orlando Gough, again; he is having a busy year. But much of the action was accompanied by a kind of collage of sound – not just sound effects like trumpets, or doors being knocked, or fire crackling, but a whole array of sounds selected and arranged for effect. The programme credits Simon Allen for something called sonic bricolage, which is not a term I recognised, but which according to the online Oxford Dictionary means “(in art or literature) construction or creation from a diverse range of available things.” The sound designer is Paul Arditti, a veteran of many shows at the National.

The concept of a soundtrack, with effects as well as music, is of course familiar in the cinema, or on television. This was very similar. Here the soundscape added to the atmosphere of horror and menace, without detracting from the rest of the show; Arditti and the live musicians took care to remain in the background, not to drown out Shakespeare’s verse. It fitted well with the concept of the production, which owed more than a little to the horror movie genre. But I also think it is a device with restricted uses, and I hope its effectiveness here will not encourage the National to disfigure other productions with unnecessary soundtracks.

——————–

——————–

A visit to Oxford : America’s Cool Modernism, at the Ashmolean

11 July 2018

A couple of weeks ago John came down to Oxted for a few days, and on the Friday, after I had spent an uncomfortable ninety minutes at the dentist, we went together to Oxford, to see an exhibition at the Ashmolean Museum: America’s Cool Modernism. It was the first time I had been to Oxford for some years, and my first opportunity to see the Ashmolean after the programme of renovations and extensions which it has undergone since 2000. John did not remember being in Oxford since he was a boy, when he came with Mum and Dad as they were driving me to or from college at the start or end of term. He had never seen much of the city, or the colleges.

We travelled by train from Paddington, and for John that was itself an adventure. Unlike the other stations which he and I use regularly – London Euston and Victoria, Manchester Victoria and Piccadilly, Birmingham New Street – Paddington has retained much of its original character, and Brunel’s beautiful wrought iron arched roof has been repainted and reglazed to make an airy, welcoming space. (Unfortunately the train departure screens do not quite match up to this standard.)

John was even more pleased to discover that some of the platforms are barrier-free, so he was able to walk towards the far end of the station and take several photographs, though he was a bit disappointed by the range of multiple-unit trains on view: no locomotives for him to gloat over. I admire multiple units for their functionality… but that’s another story.

John was even more pleased to discover that some of the platforms are barrier-free, so he was able to walk towards the far end of the station and take several photographs, though he was a bit disappointed by the range of multiple-unit trains on view: no locomotives for him to gloat over. I admire multiple units for their functionality… but that’s another story.

The main line out of Paddington is being electrified, but the wires have not yet reached Oxford, where the station has changed only superficially over the last 40 years: the same two through platforms bustling with people, the same crowded footbridge. The automatic ticket barriers are new, and the retail spaces have been extended, but it is no easier than it ever was to obtain information.

Once you get out of the station, however, the changes are everywhere. In the early 1970s, when I was at college, this area was faintly dilapidated, with large swathes of barren tarmac and old hotel buildings that had seen much better days. It has been completely cleaned up and is now dominated by the new Said Business School, named after its chief benefactor Wafic Said, a controversial Syrian-Saudi Arabian billionaire arms dealer and philanthropist. Whatever its origins the building is smart and dominant in a slightly kitschy way.

Once you get out of the station, however, the changes are everywhere. In the early 1970s, when I was at college, this area was faintly dilapidated, with large swathes of barren tarmac and old hotel buildings that had seen much better days. It has been completely cleaned up and is now dominated by the new Said Business School, named after its chief benefactor Wafic Said, a controversial Syrian-Saudi Arabian billionaire arms dealer and philanthropist. Whatever its origins the building is smart and dominant in a slightly kitschy way.

Traffic management in front of the station has been much improved too. In fact this may have been what I noticed most, all around Oxford: motor vehicles, apart from buses, are channelled along a few main streets, but there are bicycles and bicycle racks everywhere, and pedestrians can walk around in (relative) comfort. It’s almost as if the city has gone European.

We walked along New Road towards Carfax, the crossroads at the city centre, with Ruskin College on our left and Oxford Castle on our right. The castle had been used as a prison from Civil War times right up until 1996, and used to be shielded here by a high stone wall; but it has since been converted into a tourist attraction and hotel, the wall has been breached in several places, and the road now offers a more welcoming approach to the centre of Oxford. I had some difficulty dragging John away; he loves castles, but was eventually persuaded that this was more ersatz tourist attraction than authentic history.

We walked along New Road towards Carfax, the crossroads at the city centre, with Ruskin College on our left and Oxford Castle on our right. The castle had been used as a prison from Civil War times right up until 1996, and used to be shielded here by a high stone wall; but it has since been converted into a tourist attraction and hotel, the wall has been breached in several places, and the road now offers a more welcoming approach to the centre of Oxford. I had some difficulty dragging John away; he loves castles, but was eventually persuaded that this was more ersatz tourist attraction than authentic history.

At Carfax we turned right down St Aldate’s for a couple of hundred yards and then stopped for lunch in a little Italian café not far across from the main gate at Christ Church. We did peer into several of Oxford’s old inns – the Old Tom, the Bear, the Turf, the White Horse – but after my dental work in the morning I didn’t fancy grilled pub food, and though John loves his beer it does make him drowsy, not ideal when you are planning to visit an exhibition.

We walked back past Carfax, up Cornmarket, past the two churches on the right, and then left into Beaumont Street to the Museum. John kept asking me about the buildings and I was ashamed how few I could name, apart from the colleges. I had to think hard to remember the Town Hall (part of it is now a city museum.) I couldn’t identify any of the churches, or the other civic buildings. I spent four years at Oxford and was abashed to realise just how little of the city, apart from the university, I had learned.

My memories of the Ashmolean were similarly vague, but the modernisation, though discreet, is obvious: the museum has been extended backwards and upwards. We walked up three flights of stairs to find the new gallery for temporary exhibitions. Despite much publicity on posters around London and in arts publications, the gallery was not over-full and we were able to have a leisurely viewing. And the exhibition, though not large, would have been well worth the trip to Oxford even if we had done nothing else while we were there.

My memories of the Ashmolean were similarly vague, but the modernisation, though discreet, is obvious: the museum has been extended backwards and upwards. We walked up three flights of stairs to find the new gallery for temporary exhibitions. Despite much publicity on posters around London and in arts publications, the gallery was not over-full and we were able to have a leisurely viewing. And the exhibition, though not large, would have been well worth the trip to Oxford even if we had done nothing else while we were there.

I’m not sure that the label Modernism is all that helpful. The Tate website defines it as “…a global movement in society and culture that from the early decades of the twentieth century sought a new alignment with the experience and values of modern industrial life…” So far as I can see, that might encompass just about any type of painting, from Monet to Warhol. In this exhibition, however, what we mostly saw were a mixture of abstracts and built landscapes, though with the styles bleeding into one another, as in this one by the African American painter Jacob Lawrence.

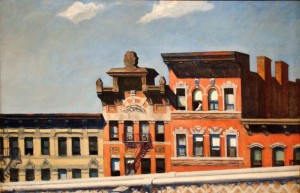

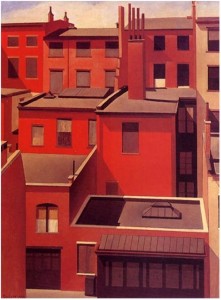

What most characterised this selection of paintings was the absence of the human form. Even where present, as in these two paintings by Edmund Hopper, all we see is a tiny figure against a massive background.

What most characterised this selection of paintings was the absence of the human form. Even where present, as in these two paintings by Edmund Hopper, all we see is a tiny figure against a massive background.

Solidity and massiveness were much in evidence, as instanced by the paintings of Charles Sheeler. Another characteristic of these images is precision: lots of clear straight lines. And just count the windows. So pervasive are they, you could almost have called this exhibition Windows on America.

Clearly defined spaces are also evident in the abstracts, including this wonderful Sunflower by Edward Steichen (who later devoted himself to photography and destroyed nearly all his paintings): for my money the outstanding exhibit here, better even than the Hoppers, and they are very good.

I was also very struck by another abstract, Sound by e e cummings (yes, the poet had a sideline in painting).

But the one painting which I actively disliked was another abstract, by Marsden Hartley, which – though it has an interesting, intricate design – is poorly executed, as if by a talented child. Perhaps the single thread running through the rest of the exhibition is a slightly alienating perfection, whether in abstract or landscape. It is an interesting perspective on the artists’ world view.

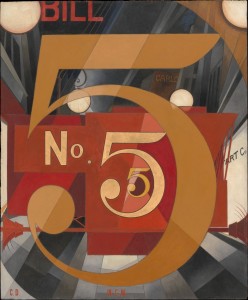

As with last year’s America after the Fall exhibition (see my blog Russians and Americans, 8 April 2017), you can see in many of these paintings the seeds of later commercial art and design. Perhaps this is most visible in Charles Demuth’s striking I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold, another abstract/landscape, drawing inspiration from a poem by the painter’s friend Walter Carlos Williams. You would not be the least bit surprised if this was in fact advertising a brand of No.5 cigarettes.

After the exhibition we wandered round Oxford for a bit longer. I think John would have liked to see more of the Ashmolean’s permanent exhibits, but they clearly deserved more time than we had. In one respect the museum does not seem to have changed much from my memories of forty years ago: the exhibits are packed into the display cases, clearly intended more for the devoted student of archaeology and art than for the casual tourist with a visitor’s guide. In other words, they demand your full attention. But we saw enough to know we want to see more. We shall be back.

After the exhibition we wandered round Oxford for a bit longer. I think John would have liked to see more of the Ashmolean’s permanent exhibits, but they clearly deserved more time than we had. In one respect the museum does not seem to have changed much from my memories of forty years ago: the exhibits are packed into the display cases, clearly intended more for the devoted student of archaeology and art than for the casual tourist with a visitor’s guide. In other words, they demand your full attention. But we saw enough to know we want to see more. We shall be back.

——————–

Maria Aberg’s Duchess

10 July 2018

Last Saturday John and I, with my friends Janet and Chris Pitt-Lewis, went to the theatre in Stratford to see the RSC’s production of The Duchess of Malfi, written by John Webster in 1612-13, and here directed by Maria Aberg. We had read in the early Press reviews that this was a bloody, expressionist production which focused on the feminist themes in the play. John and I last saw the play in 2012, at the Old Vic, with one of our most admired actresses Eve Best in the title role. But none of us had much memory of the play, though as it is a Jacobean tragedy we were fairly sure that everyone would die.

Last Saturday John and I, with my friends Janet and Chris Pitt-Lewis, went to the theatre in Stratford to see the RSC’s production of The Duchess of Malfi, written by John Webster in 1612-13, and here directed by Maria Aberg. We had read in the early Press reviews that this was a bloody, expressionist production which focused on the feminist themes in the play. John and I last saw the play in 2012, at the Old Vic, with one of our most admired actresses Eve Best in the title role. But none of us had much memory of the play, though as it is a Jacobean tragedy we were fairly sure that everyone would die.

The performance lasted just over two and a half hours, including interval, and used a text that had been heavily cut. This seems an increasingly common practice and I am starting to wonder whether directors are taking it too far. Three named characters in Webster’s original text, Castruchio, Pescara and Malateste, were omitted altogether. Who knows what we missed?

Quite possibly, a bit of context. Jacobean tragedy often concocts more or less implausible plots in order to arrive at a final cathartic bloodletting, but even so in this retelling the story seemed almost incoherent. The newly widowed Duchess, without many preliminaries, fastens upon Antonio to be her lover and husband. The marriage is kept secret for long enough for them to have three children – time which passes, on stage, almost unnoticed and unremarked; we just have to work it out for ourselves. Then her evil brothers, Duke Ferdinand and the Cardinal (unnamed), discover the marriage and plot to destroy it. They enlist the services of a mercenary, Bosola, who repents after murdering half the cast, and murders most of the others.

All the main characters, except perhaps Antonio who is a bit of a cipher, are psychologically interesting. They were well portrayed, especially Duke Ferdinand (played by Alexander Cobb) and the Duchess herself (Joan Iyiola). There is a subtext that Ferdinand incestuously loves the Duchess, which at the Old Vic was made explicit but was almost invisible here. Only the Duchess’s motivation, to be her own self and choose her own partner without regard to tradition or propriety – Antonio is not of her social class – is really made clear in this production. We are clearly meant to understand that it is this assertion of her rights as a woman, in a society in which men expect and are expected to call the shots, that drives Ferdinand and the Cardinal to anger. But their murderous response seems out of all proportion, because the abridged text lays so little groundwork for it. Bosola (Nicolas Tennant), who starts wicked and ends repentant (and dead), should be arguably the most interesting of all, but here you had to pay quite a lot of attention even to notice.

All that said, so long as you are not worried by incoherence of plot and character, this was a highly dramatic telling of the tale. And most importantly, the cast spoke their lines clearly and with meaning from the outset. Iyiola, in particular, was exemplary. I often find at performances of Elizabethan and Jacobean drama that it takes ten minutes or so to tune in to the dialogue, as I reaccustom myself to its rhythms and idiom. Even the RSC, which is the best of our theatres in this respect, has had its share in recent productions of actors who are too shrill, or who simply speak the lines too fast. That was not the case here at all. It was the production’s one outstanding feature.

All that said, so long as you are not worried by incoherence of plot and character, this was a highly dramatic telling of the tale. And most importantly, the cast spoke their lines clearly and with meaning from the outset. Iyiola, in particular, was exemplary. I often find at performances of Elizabethan and Jacobean drama that it takes ten minutes or so to tune in to the dialogue, as I reaccustom myself to its rhythms and idiom. Even the RSC, which is the best of our theatres in this respect, has had its share in recent productions of actors who are too shrill, or who simply speak the lines too fast. That was not the case here at all. It was the production’s one outstanding feature.

As usual at Stratford the stage set and props were minimal. Against the back wall was a short row of orange plastic chairs, the kind you can stack up. Goodness knows what they were supposed to tell us. In front of those, two parallel lines of railings, as on a football terrace. A few steps down, and a ledge from under which, early in the play, a double bed was pulled, right to the front of the apron stage. That at least was an understandable prop. To the right, suspended from the ceiling by a long chain, was the over-size, distended, headless body of a pig – at least I think it was a pig, complete with trotters. A male chauvinist pig, perhaps? In the opening scene the Duchess pulls on the chain but succeeds only in raising the body of the pig, which had been lying on the floor, to a vertical position. I suppose this was symbolic too.

As usual at Stratford the stage set and props were minimal. Against the back wall was a short row of orange plastic chairs, the kind you can stack up. Goodness knows what they were supposed to tell us. In front of those, two parallel lines of railings, as on a football terrace. A few steps down, and a ledge from under which, early in the play, a double bed was pulled, right to the front of the apron stage. That at least was an understandable prop. To the right, suspended from the ceiling by a long chain, was the over-size, distended, headless body of a pig – at least I think it was a pig, complete with trotters. A male chauvinist pig, perhaps? In the opening scene the Duchess pulls on the chain but succeeds only in raising the body of the pig, which had been lying on the floor, to a vertical position. I suppose this was symbolic too.

The characters remarkably fail to notice this bizarre object all through the play except directly after the interval when Ferdinard, surrounded by his cronies, carves a great gash in the pig’s belly. Thereafter blood seeps out of the wound and slowly across the stage, even dripping down the sides (audience members in the front row were given protective gear). By the end of the play just about all the characters were dripping with the stuff. An effective image, but a bit OTT: at one stage I was wondering about how it was made, as the usual formula for stage blood would scarcely have sufficed, while Chris was speculating on the cleaning bills. I’m not sure that an expressionist device can be entirely successful if it makes you think not about what it signifies but how it is done.

Music was by Orlando Gough, a contemporary of mine at college. He has written music for several other plays we have seen recently, and from his website I see that he has developed a solid career as (among many other projects) a composer for the stage. One of his particular qualities is that he is equally at home in a wide variety of idioms: in this show, a heavy metal number, a blues, a beautiful piece for counter-tenor and an even better wordless lament, faultlessly performed and reprised by Iyiola. The blues (sung by Aretha Ayeh, playing the Cardinal’s mistress whom he later murders) doesn’t really fit, but is just about acceptable for the emotion expressed. That heavy metal, though: it accompanies a dance number, early in the production, in which the men in the cast perform violent macho routines. Not remotely justified by the action of the play; all with the purpose of driving home a point we had already understood. I hated this. We would have been much better off with five minutes more of Webster and five less of posturing.

Perhaps I was more irritated by the music than I need have been because of an absurd programme note, not by Orlando but by the show’s music director David Ridley, in which he accuses generations of musicians of misogyny because of how musicology uses the terms masculine and feminine. (For the record, I have never used these terms in the way described.) Orlando’s own account of how the music was conceived is far more convincing: http://www.orlandogough.com/present-projects-2 (you need to scroll down a bit).

He notes the same criticism that I make of this interpretation of the play, though politely, as befits a member of the production team: “you could argue that there is more to it than [the misuses of masculinity] – issues of class, honour, jealousy, greed.”

All together, I enjoyed the production. It was well acted, very well spoken, contained some powerful images and some of the music was very good. But I think there was too much Aberg in it and not enough Webster.

——————–

More school cricket

10 July 2018

Most of the photographs I use in these blogs come from one of three places. I find them online, or John provides them, or I select them from our digitised archive of slide transparency photos taken by my parents. Unfortunately, none of these three sources helps much when it comes to my cricketing memories. Dad used to come to watch me playing cricket when he could: during the period 1969-1971 he was managing his recovery from malignant hypertension, and was able to take the time off work. But he doesn’t seem to have taken any pictures, or if he did they have been lost.

He did, however, share some of my exploits with the family. After my year as captain of the Colts I was hoping to find a place in the 2nd XI (all ages) but to begin with I was not selected: another boy, Pete Wilson, a bit bigger than me but with (I dare say) no more cricketing talent and a lot less cricketing knowledge, was preferred. However, he was for some reason unavailable for an away match against Caldy Grange school, on the Wirral, and I was asked to play.

The 2nd XI were a better team than the Colts (not difficult), and in particular we had a boy called Graham Schofield, a properly quick bowler and a good batsman too. Graham was good enough for the 1st XI, but preferred the 2nds where he had more opportunities, particularly to bowl. Anyway, I was stationed to field at second slip when Graham was bowling, and managed to take a good catch there: it came straight to me, but quickly and very low. I don’t think Pete would have caught it.

Our captain didn’t however think very much of my batting, and I was not sent in to bat until number 10. We were being beaten, but if I could hold out for a few overs (let’s say 8 – it might have been 6, or 10) we would scrape a draw. I blocked all the straight ones and left all the wide ones. I made no attempt to score any runs. The fielders came in closer and closer, but my dead-bat defence, owing everything to Trevor Bailey, gave them not a chance, and the match was drawn. Unknown to me, Dad had come to watch at some point during our innings, so he witnessed this dramatic rearguard, and told the family about it. John noticed I’d not included this story in the previous blog; so here it is. After that, of course, I was a regular selection, and sometimes I batted a bit higher up the order too.

I don’t in fact remember all that much of our cricket that year; I must have batted from time to time, I guess without much success, but after Caldy I don’t remember a single other innings that I played. On rare occasions I was also invited to bowl, and I still have a vivid memory of taking three wickets against St Mary’s Crosby. Our captain was Ken Spain and I think he just wanted to get me involved. I was still trying to bowl off-breaks, using a very short run-up, but on this occasion I suddenly started to make the ball swing through the air, great looping inswingers changing direction by 10 or 12 inches in flight, which bewildered the batsmen about as much as it surprised me. In the course of six or seven overs I had one batsman lbw, one caught at square leg, the third caught and bowled.

Then Ken took me off. I was most disappointed. I had (I thought) an excellent chance of taking five in an innings, and then my name would have been read out at school assembly the following day. Everyone knew I was bright, but to demonstrate sporting prowess would definitely have earned me some extra respect. Of course, it would not have been wholly deserved. It hadn’t been my intention to make the ball swing like that; I was just smart enough to take advantage when it did. And I still don’t know why it happened. Over later years I discovered that my bowling action (probably my wrist position) naturally imparted a small amount of inswing, but I never again achieved that much loopiness.

During the summers of 1969 and 1970, when I was in the sixth form, I played for either the 1st or the 2nd XI, as opportunity and the need arose. Our 1st XI had some decent cricketers: among others, a left-arm pace bowler Mal Harris who actually had a trial with Lancashire 2nd XI and so is immortalised in Wisden, and a fine batsman and leg-spin bowler Geoff Pollard who went on to play regularly in the Liverpool Competition (that is one step below county 2nd XI level).

Geoff features in another of my memories. There was an annual match, quite hotly contested, between the 1st XI and the school masters, some of whom were seriously good cricketers. We batted first and set them a moderate target, but bowled well enough that with their last man in they were still short. Geoff was bowling; we had set a close field, and I was standing at slip. The batsman, not one of their best, edged the ball and it flew high over my right shoulder. I remember momentary gasps of disappointment from the other fielders, which turned to congratulations when I stuck out my right hand and caught it as I stretched backwards. I don’t think I have ever taken a better catch, and I have certainly missed easier ones.

One of the best of our players was Andy Baker, who was 1st XI captain in my last year at school. I remember our match at Manchester Grammar: he declared when he was himself 96 not out. We couldn’t believe it. I don’t think he knew; it wasn’t quixotic, just unselfconscious. Centuries in schools cricket are rare, and in fact in all the cricket matches I have ever played there has only been one century, made by a brilliant West Indian batsman whom I had dropped when he was still in single figures. Not one of my best memories, but – unlike the catch – it has stuck.

However, that was many years later. My one other clear memory of school cricket also come, I think, from 1970: at any rate I was playing for the 1st XI against our old boys team, the Liobians. We batted second and I went in at number 3 (you see I had climbed in the order a bit). The Liobians had a really good medium-fast bowler called Phil Isaacs, who mostly bowled outswingers but could also deliver an inswinger on occasion. That’s a dangerous combination. He had all our batsmen in trouble, except me. I took most of his bowling, and left everything I could, including several deliveries which started on the stumps and swung away, much to Phil’s annoyance. But somehow I also detected the inswingers which started just outside off stump but had to be blocked. I had no idea, then or now, how I was able to tell the difference; was there a subtle change in his action which I unconsciously noted? Was I simply playing the line? Was I guessing? Whatever, it worked: I batted 70 minutes for 4 not out, and we won by seven wickets.

Of course the other boys teased me mercilessly for my Boycott-like batting, but I didn’t care. I had achieved my goal of neutralising the most dangerous bowler, and so ensured that we were able to win. The following year I played for the Liobians and got to know Phil quite well. He teased me too, but I think there was a bit of respect in it: he had not been able to get me out, and he had certainly tried.

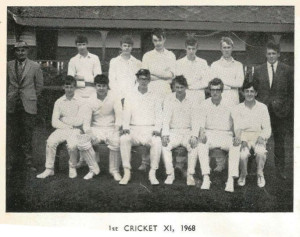

Here is the only vaguely relevant photo I have been able to find: the Liverpool Institute First XI in 1968. I’m not in it, but several of the other players I’ve mentioned can be found here: back row, from left, Les Abbie and Mal Harris; from right, Andy Baker and Graham Schofield; front row, Steve Tetlow at left, Geoff Pollard at right. The master in charge, on the right wearing a suit, is John Grace, who I remember once gave me out lbw, padding up outside the off stump against an off-spinner. I didn’t think I was out, and he told me afterwards that he had just wanted to teach me a lesson. As I had just played a straight drive for 3, with which I was rather pleased, I thought it was a bit uncalled for, but my defensive reputation had preceded me. The photo is from the Liobians website. Unfortunately the focus is poor, but it’s all I have.

——————–

——————–

Cricket captain

3 July 2018

Between the ages of eleven and seventeen, I attended the Liverpool Institute High School for Boys. The Institute was well known as the best grammar school in Liverpool, with a fine academic record, and I have good memories of my time there. Among those memories is the term which I spent, then aged fifteen, as the captain of the Colts (15 and under) cricket team. The year was 1968.

I have been fond of cricket ever since I was quite a small boy. Dad gave me a cricket bat when I was nine years old; I remember taking it to school and playing cricket, with a tennis ball, in the playground during breaks. I also remember on a holiday in Cwm Pennant, in North Wales, playing with Dad on a patch of flat ground next to the cottage which we had rented. I hit the ball into the manure heap.

I remember my first game for the Colts. I was pleased to have the opportunity, as I had missed school cricket in both the previous years: in 1966 I was absent for most of the summer term because of my asthma, and in 1967 I was recovering from appendicitis. The game was against Hillfoot Hey, another local school, and our captain was a boy called Paul Rodgers. He was our best bowler, and a decent batsman too – in fact, a much better cricketer altogether than I was. But all the decisions – batting order, field placing, bowling changes – were in fact taken by the master in charge, who was also umpiring at one end. After the match was over I remember suggesting to him that I might be able to help with the captaincy, whereupon he promptly appointed me to replace Rodgers. (In those days, the boys mostly knew each other by our surnames.) To his credit I don’t recall that Rodgers resented this; he may even have been a little relieved.

We were not a very good team. Our one saving grace was that we had two good opening bowlers, Rodgers and a boy called Graham Jackson. I had private reservations about Jackson’s bowling action, but I kept them to myself. After those two we didn’t have much else. Our batting was awful. None of our batsmen exceeded 20 during the whole term: that was by Norman Raby, our opening batsman. My personal top score was 19, so I suppose I was pulling my weight, such as it was. We’ll come back to that.

For most of the term we didn’t win a single match and lost most of them. We drew one, against a school in Birkenhead, which we ought to have won but for what we thought were blatant delaying tactics orchestrated by our opponents’ master in charge, who was umpiring. All I remember about that match, now, is the indignation which we felt afterwards. On another occasion, against St Mary’s school in Crosby, I remember their batsmen stealing a run when our fielders were sloppy in returning the ball to the bowler. The batsmen were within their rights, but I thought it sharp practice: once the ball has been returned to the wicket keeper, the rules do not allow runs to be stolen in this way, but to return the ball to the keeper every time slows the game down, so it seemed to me that St Mary’s were taking advantage of our laudable willingness to keep the game moving.

There was one match in which we were hopelessly outclassed by an under-15 team from Manchester Grammar School. I suppose it was traditional for the Institute, as Liverpool’s premier grammar school, to arrange fixtures against its equivalent in Manchester, but the truth is that they were light years ahead of us. A few years later Manchester Grammar would go on to provide several county cricketers for Lancashire, two of whom, Mike Atherton and John Crawley, eventually played for England.

To make matters worse we played not on the Institute’s primary ground, at Mersey Road, but on the reserve ground at Riverside Road. There was a considerable difference in the quality of the pitches. Anyway, Manchester turned up with three fearsome fast bowlers, put us in to bat, and wreaked havoc.

That was the match in which I made 19. I had in my mind, I think, that I had been taught to keep my eye on the ball, and not to back away. I also had decent forward and backward defensive shots, which I had learned from careful study of a coaching book Dad gave me a couple of years earlier, Trevor Bailey’s Improve Your Cricket.  I must have frustrated the Manchester boys a bit, because at one point they brought on a slow left arm spinner, hoping (I thought) to tempt me into an indiscretion. It didn’t work. 12 of my 19 runs came from ambitious cover drives against the fast bowlers that I edged safely over the close fielders’ heads down to the boundary, which no doubt irritated the bowlers some more. When I eventually got out I remember I was given a sympathetic round of applause by the fielders: I had been outclassed, but not cowed. That probably earned me some credibility with my own team too.

I must have frustrated the Manchester boys a bit, because at one point they brought on a slow left arm spinner, hoping (I thought) to tempt me into an indiscretion. It didn’t work. 12 of my 19 runs came from ambitious cover drives against the fast bowlers that I edged safely over the close fielders’ heads down to the boundary, which no doubt irritated the bowlers some more. When I eventually got out I remember I was given a sympathetic round of applause by the fielders: I had been outclassed, but not cowed. That probably earned me some credibility with my own team too.

After six or seven matches without a win I was getting a bit desperate, and suggested to the master in charge that we should make a couple of changes to the team, bringing in players whom I had seen elsewhere: Ollie Mortensen, to keep wicket, and Paul Carter, to open the bowling. He agreed, but made me break the bad news to the players who were being replaced, which I hadn’t expected; but I suppose it was fair enough. One of them, Steve Peers, didn’t really deserve to be dropped as he was our best fielder. He made his feelings known, and refused to be selected for our remaining matches. I still feel a bit guilty about that.

The next match was against St Margaret’s school in Aigburth and I remember quite a lot about it, starting with the fact that I spent about half an hour trying to find the sports ground. We bowled first, and Carter was a disaster: I had to take him off after a couple of overs, but fortunately Rodgers and Jackson were able to restore order. We chipped away, but eventually I had to change the bowling, and brought myself on to bowl as third change, against (I think) their numbers 7 and 8. In those days I was a slow spinner, trying to bowl off-breaks.

I didn’t turn the ball much, or at all, but I had an unusual bowling action and a low trajectory which occasionally fooled the batsmen. In my second over the number 7 holed out to midwicket, whereupon I took myself off straight away and brought back Jackson, who polished off their tail-enders. In our reply, I made only 5, but everyone chipped in a bit and we won by five wickets. Mortensen had kept wicket neatly, and was batting when we reached our target. Not everything I tried had worked, but overall I felt that my leadership had contributed to the victory.

Alas, the season concluded on a less happy note. Our last match was against local rivals Quarry Bank, and none of our other teams was playing that day, so I was able to bring into the team a couple of my friends who would otherwise have been in the First XI, Les Abbie and Steve Tetlow. I opened the innings myself, in partnership with Steve, but for the first five or six overs we were not able to scratch a single run between us. It couldn’t last: eventually we tried to snatch a single that wasn’t there, and I was run out. Neither Steve nor Les did much better. I gave them both an opportunity to bowl, but with no more success, and Quarry Bank won easily. All I remember from their innings is that they had a batsman who struck a couple of straight drives, quite an unusual shot for a boy cricketer; I adjusted the field placing, to cut off the shot, and earned approval afterwards for this astuteness. But in my heart of hearts I think I felt that Les and Steve was a bit too much like ringers, players added to a team who are not properly qualified to play for it; perhaps we deserved to lose.

In later years I captained other teams occasionally: my college team at Oxford once (in that match also, I secured our first victory of the season after several failures), my London club once, both times in the absence of our regular captains. But it wasn’t the same.