Ministry of Flat Walks 14 : Gait Barrows

30 September 2018

To follow this walk on a map, open another tab on your browser and input this address: https://bit.ly/2NbZgnT.

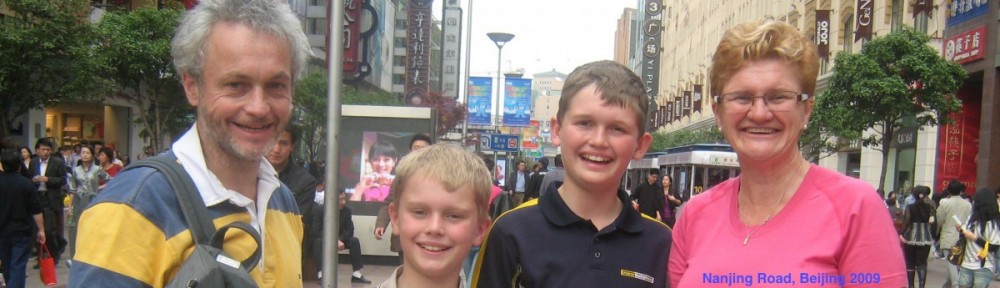

John and I have attempted this walk twice this year, and eventually completed it yesterday. In time it may become a favourite, as it is a good length (4-5 miles), without many gradients and none of them severe, in pleasant and varied countryside, mostly along clearly defined paths but with little road walking. Our first attempt was incomplete because one of the paths was closed – but more of that later on.

The route lies wholly within the Arnside and Silverdale Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, and passes round and through the Gait Barrows Nature Reserve which is owned and maintained by Natural England (a Government-sponsored agency). The walk starts near the village of Yealand Storrs, in the south east corner of the map. Just to the west of the village is a road junction, with a single chevron on the map to show that the road westwards goes down a significant hill at this point. The road northwards is signposted to Arnside and Milnthorpe, and immediately on the left hand side of this road is a parking space with room for several cars. You should be able to park here, as we did.

Between the westward and northward roads is a footpath, the entrance to which is gated. Go through this gate and follow the path. There are trees on either side, and in the sunshine the leaves, now showing their autumn colours, are very attractive. A little way along you will come to another gate; go through that too. After half a mile or so the trees on the left give way to a stone wall, through which there is a narrow stile. You will be coming back this way. For now, continue along the path.

Between the westward and northward roads is a footpath, the entrance to which is gated. Go through this gate and follow the path. There are trees on either side, and in the sunshine the leaves, now showing their autumn colours, are very attractive. A little way along you will come to another gate; go through that too. After half a mile or so the trees on the left give way to a stone wall, through which there is a narrow stile. You will be coming back this way. For now, continue along the path.

You will soon come to a junction with paths leading left and right. Don’t miss it; the leftward branch is not visible until you get quite close. Turn left here and go down the hill, now with meadow behind a wall to your left. At the bottom of the hill is a gate, but just before you get there you will see a path leading off through a stile to the right.

You will soon come to a junction with paths leading left and right. Don’t miss it; the leftward branch is not visible until you get quite close. Turn left here and go down the hill, now with meadow behind a wall to your left. At the bottom of the hill is a gate, but just before you get there you will see a path leading off through a stile to the right.

Take that path, which is less well defined than previously, and follow it up a slight incline. After a hundred yards or so it opens out into a meadow. This next section of the walk may cause you a few moments’ hesitation, as there is no proper path across the meadowland, although you may just be able to see how the grass has been flattened by previous walkers. But if you look ahead you should be able to spot route markers (yellow arrow signs, on posts or fixed to fences or walls), and when you come to the next line of trees the path is clearer.

Take that path, which is less well defined than previously, and follow it up a slight incline. After a hundred yards or so it opens out into a meadow. This next section of the walk may cause you a few moments’ hesitation, as there is no proper path across the meadowland, although you may just be able to see how the grass has been flattened by previous walkers. But if you look ahead you should be able to spot route markers (yellow arrow signs, on posts or fixed to fences or walls), and when you come to the next line of trees the path is clearer.

Continue to the second line of trees where you will find two gates set at right angles and a stile between them. Cross the stile into the next meadow. There is now no defined path at all, but the way ahead should be clear enough, keeping fairly close to the woods on your left and looking out for route markers. We crossed first through a wooden gate in a wire fence, then across a line of stones which bisect the field (you can just see these on the map), then through another two stiles, and finally downhill to a gate which opens out into the road at Leighton Beck Bridge.

Continue to the second line of trees where you will find two gates set at right angles and a stile between them. Cross the stile into the next meadow. There is now no defined path at all, but the way ahead should be clear enough, keeping fairly close to the woods on your left and looking out for route markers. We crossed first through a wooden gate in a wire fence, then across a line of stones which bisect the field (you can just see these on the map), then through another two stiles, and finally downhill to a gate which opens out into the road at Leighton Beck Bridge.  The stream here forms the county boundary between Lancashire and what is now Cumbria but used to be Westmorland, and someone has carefully maintained the old boundary marker.

The stream here forms the county boundary between Lancashire and what is now Cumbria but used to be Westmorland, and someone has carefully maintained the old boundary marker.

Turn left along the road for fifty yards or so and then right along a well-used farm track. Even after a very dry summer we found the track hereabouts was quite damp and muddy, so be prepared. The track runs parallel to the beck and peters out in front of a gap in a wall, with another wall leading ahead and away from you. Continue straight ahead, keeping the wall on your left. From here, on a clear day, almost straight ahead in the middle distance you should be able to see a barred gate in a line of hedge. That is where you are heading for. Presently you will cross into another field, with a hedge and a ditch on your right. After another hundred yards or so you there is a rough-and-ready wooden footbridge across the ditch. Go across this bridge, turn left and head directly for the gate.

Go through the gate and turn left along the bridleway. In the field to your left you may see, as we did, a flock of pheasants, which a passer-by told us are being kept by a local farmer. I thought pheasants were hunted and shot, not farmed. Why don’t they escape? Anyway, you should continue along this bridleway for another quarter mile or so until you come to a road. Hazleslack Farm (top left corner of the map) is to your right, and appears to be one of the old fortified farmhouses you can see in the north, protecting against raids by Scots and Celts. But even for John it is only a moderately interesting structure.

Go through the gate and turn left along the bridleway. In the field to your left you may see, as we did, a flock of pheasants, which a passer-by told us are being kept by a local farmer. I thought pheasants were hunted and shot, not farmed. Why don’t they escape? Anyway, you should continue along this bridleway for another quarter mile or so until you come to a road. Hazleslack Farm (top left corner of the map) is to your right, and appears to be one of the old fortified farmhouses you can see in the north, protecting against raids by Scots and Celts. But even for John it is only a moderately interesting structure.

Turn left here and follow the road (which is very quiet) down to a T junction. There may be a bit more traffic here. Turn left again for a hundred yards or so and then go through a stile in the wall to your right. We found a post here which was probably a footpath sign that has been broken off. I suppose it may be mended sooner or later; you may find it has been repaired.

Turn left here and follow the road (which is very quiet) down to a T junction. There may be a bit more traffic here. Turn left again for a hundred yards or so and then go through a stile in the wall to your right. We found a post here which was probably a footpath sign that has been broken off. I suppose it may be mended sooner or later; you may find it has been repaired.

From the stile, turn left, but not too sharp left. There is a line of trees to your left, but with a gap more or less ahead of you. Go through the gap and down a short slope to a gateway without a gate in a fence. From here you should be able to see a stile across to your right. After crossing the stile, you should find you are back on a recognizable path. Follow this path through the woods for another quarter mile or so up to the next road.

This is where our previous attempt at this walk came to a halt. Directly across the road is another path, but it had been closed by Natural England for repairs. We nonetheless ventured along it for a couple of hundred yards and found the reason for the closure: a group of workmen were constructing a boardwalk across a marshy area on the edge of a shallow mere, named on the map as Hawes Water. (There is another Haweswater, a large artificial reservoir in a valley south of Penrith. Don’t be confused.) On that occasion we had to turn around and return to our car by walking along the road for a mile and a half, which wasn’t much fun. Better signage would have been helpful. However, the boardwalk is now complete and yesterday we were able to proceed unhindered.

Anyway. Cross the road and walk down through the woods until you come to a wall. Turn left in front of the wall and you will soon find Hawes Water on your right. Follow the boardwalk and turn left through a gate into a pasture. The path here is not very worn but can be seen heading upward across the pasture. Follow this path, across one stile and up to a second, where your path crosses another and there is a signpost. Continue straight ahead and you will soon come back to the stile in the stone wall which I mentioned at the start of the walk. And so back to your car.

Anyway. Cross the road and walk down through the woods until you come to a wall. Turn left in front of the wall and you will soon find Hawes Water on your right. Follow the boardwalk and turn left through a gate into a pasture. The path here is not very worn but can be seen heading upward across the pasture. Follow this path, across one stile and up to a second, where your path crosses another and there is a signpost. Continue straight ahead and you will soon come back to the stile in the stone wall which I mentioned at the start of the walk. And so back to your car.

As you can see from the map, this whole area is crisscrossed with paths, and many variations in the route are possible. But do keep an eye on the contour lines. The area in the centre is a limestone outcrop into which I have not ventured, and will certainly require some scrambling if you do.

Thanks to John for his excellent, if sometimes unflattering, photographs.

——————–

——————–

Tamburlaine

27 September 2018

Last weekend John, Janet, Chris and I went to Stratford-on-Avon to see the RSC’s current production of Tamburlaine, by Christopher Marlowe. Strictly speaking I suppose I should describe it as an adaptation by director Michael Boyd and his assistants, since the original was not one play but two, which are here edited down into a single 3-hour version. Apparently the second part was written by Marlowe in response to public demand: the first instance that I can recall of the sequelitis (https://bit.ly/2xKDRxi) which now plagues movie-making, television and computer games.

Last weekend John, Janet, Chris and I went to Stratford-on-Avon to see the RSC’s current production of Tamburlaine, by Christopher Marlowe. Strictly speaking I suppose I should describe it as an adaptation by director Michael Boyd and his assistants, since the original was not one play but two, which are here edited down into a single 3-hour version. Apparently the second part was written by Marlowe in response to public demand: the first instance that I can recall of the sequelitis (https://bit.ly/2xKDRxi) which now plagues movie-making, television and computer games.

The plays were tremendously successful in their day, but fell out of favour quite quickly thereafter, and have never really re-established themselves in the repertoire. Their original success seems to have been caused by a combination of factors including novelty and exoticism, sensation and notoriety. At the time they must have seemed quite edgy. Tamburlaine disdains gods, whether classical, Christian or Islamic; Marlowe himself reputed, shockingly, to be an atheist. And the story, in which an upstart from a  background triumphs over the established ruling class, must have had resonance in an England where the old aristocracy was being challenged by religious change, by social mobility and the appearance of a middle class, especially in London. In modern terms, Marlowe’s Tamburlaine captures the zeitgeist.

background triumphs over the established ruling class, must have had resonance in an England where the old aristocracy was being challenged by religious change, by social mobility and the appearance of a middle class, especially in London. In modern terms, Marlowe’s Tamburlaine captures the zeitgeist.

But the reasons for the plays’ eclipse are also not hard to imagine. They are lengthy (even this abridged version lasts over three hours), require a large cast of actors in mostly unrewarding roles, and place an enormous burden on the protagonist, who is rarely off-stage. And the story which they tell might easily become monotonous. Tamburlaine proceeds from one victory to the next, performing horrendous acts of cruelty along the way, until he eventually dies, not at the hands of his enemies but from a seizure, brought on (we might imagine) by excess or exhaustion, or both. Characterisation, except for Tamburlaine himself, is minimal. There is little dramatic tension.

For the play to be successful thus requires an actor of unusual power, charisma and stamina, to command our attention and retain our interest. In this production Tamburlaine is played by a black actor whom I had not previously seen, Jude Owusu. We see his charisma at work early on when he induces an opposing general, Theridamas, to change sides. He makes Tamburlaine’s grotesque cruelties seem natural to his character and background, the upstart who sweeps all before him by being more decisive and ruthless than his enemies can imagine. And when his beloved wife Zenocrate dies, early in the second part, he becomes even more driven, more desperate; we can see how her death has pushed him over the edge.

For the play to be successful thus requires an actor of unusual power, charisma and stamina, to command our attention and retain our interest. In this production Tamburlaine is played by a black actor whom I had not previously seen, Jude Owusu. We see his charisma at work early on when he induces an opposing general, Theridamas, to change sides. He makes Tamburlaine’s grotesque cruelties seem natural to his character and background, the upstart who sweeps all before him by being more decisive and ruthless than his enemies can imagine. And when his beloved wife Zenocrate dies, early in the second part, he becomes even more driven, more desperate; we can see how her death has pushed him over the edge.

Owusu commands the stage, as the role requires. But he also speaks the verse with clarity and conviction. Marlowe never lets up: every speech, every sentence, every line of iambic pentameter is suffused with rhetorical power, heightened language that could easily collapse into self-parody. Owusu is equal to the challenge. He uses the power of Marlowe’s verse to underpin Tamburlaine’s glamour and charisma. Yet he also responds to the poetry. There is a speech early in the play, when Tamburlaine meets Zenocrate and is smitten by her beauty:

Zenocrate, lovelier than the love of Jove,

Brighter than is the silver Rhodope,

Fairer than whitest snow on Scythian hills,

Thy person is more worth to Tamburlaine

Than the possession of the Persian crown…

Owusu delivers this, and acts it, flawlessly. On this showing he is a major talent. I would love to see him as Henry V, or Richard III, or Antony, or Macbeth.

It is hard to compete with such a charismatic figure on stage, but I was also very impressed with Rosy McEwen, in her first role at the RSC, as Zenocrate. She is ice to Tamburlaine’s fire. While Owusu flings himself around the stage, McEwen is still and self-contained. She makes what could be an almost entirely passive role into something much stronger. She, like Theridamas, has been captured by Tamburlaine’s charisma, but she retains a pride and hauteur of her own. She is never a mere satellite revolving around him, but an alternative centre of gravity, so it makes sense that when she dies he goes off the rails.

It is hard to compete with such a charismatic figure on stage, but I was also very impressed with Rosy McEwen, in her first role at the RSC, as Zenocrate. She is ice to Tamburlaine’s fire. While Owusu flings himself around the stage, McEwen is still and self-contained. She makes what could be an almost entirely passive role into something much stronger. She, like Theridamas, has been captured by Tamburlaine’s charisma, but she retains a pride and hauteur of her own. She is never a mere satellite revolving around him, but an alternative centre of gravity, so it makes sense that when she dies he goes off the rails.

In such an epic production, with 44 different named characters and many other hangers-on, there is inevitably some doubling of parts. Indeed Mark Hadfield, who plays successively two kings and a jailer, makes a joke out of it with a nod and a wink to the audience. James Tucker turns up as a series of wily, cowardly opportunists: the programme notes list him in five different roles, looking exactly the same each time, and we are clearly meant to make the connection.

In McEwen’s case, however, doubling causes problems. In the second half of the play she is also given the role of Callapine, an emperor of Turkey who manages to escape and eventually outlive Tamburlaine. Her performance distinguishes neatly between her roles, but she is given so little time to switch from one to the other that there is no costume change, and this makes Callapine an ambiguous figure. If Michael Boyd is making a point here it doesn’t come through, and I think could have been better managed.

In fact the second half of the show, roughly corresponding to Part II of Marlowe’s original, is generally weaker. Typical of many sequels, it is more repetition than development. No amount of clever or subtle direction can conceal this; but it does seem a mistake that the exotic curved swords carried by Tamburlaine and his supporters in the first half are replaced, in the second, by rifles and machine-guns. Costuming in the play is unobtrusively present-day, so the modern weapons are not out of place, but the lack of consistency makes no sense that I can see.

Some early reviews suggested that this is an excessively bloody production. Given the story, it would not have been surprising if this were so: there are many murders and battle scenes. But in fact most of the violence is heavily stylised. Battles take place offstage. Violent deaths are symbolised by an unnamed, shrouded figure carrying a bucket and paint brush; he paints the faces, and sometimes clothing, of the dead in brushstokes of bloody red. This has two effects: the meaning is clear without the absurdity of a bloodbath, and the rare on-stage violent acts are all the more shocking, as for instance when the captive Bajazeth bashes his brains out on the cage in which he is confined.

The programme notes invite us to see a parallel between Tamburlaine, who recognises no constraints on his actions, and the modern post-rules universe in which Trump, Putin and others behave as if the law has no meaning for them. I can see some parallel with Trump, who was consistently discounted by the political elites until he was elected and has since been met with a mixture of fawning and loathing. But it is only a loose equivalence. Fortunately the production never makes the contemporary echoes explicit. No-one is given an orange wig or a fake golden tan. At most Tamburlaine offers a warning, not a lesson. He shows us what may happen when power is unfettered by law or morality, but not how, or even whether, it may be brought to heel.

——————–

Mortality plays

8 September 2018

John came to stay with me in Oxted last weekend, and we went to the theatre twice: to see Alan Bennett’s new play Allelujah! at the Bridge Theatre, which we hadn’t previously visited, and then a revival of Eugène Ionesco’s Exit the King at the National Theatre. We also went to see Aftermath at the Tate Britain, an exhibition of art in the wake of World War One, but that will have to wait for another blog.

John came to stay with me in Oxted last weekend, and we went to the theatre twice: to see Alan Bennett’s new play Allelujah! at the Bridge Theatre, which we hadn’t previously visited, and then a revival of Eugène Ionesco’s Exit the King at the National Theatre. We also went to see Aftermath at the Tate Britain, an exhibition of art in the wake of World War One, but that will have to wait for another blog.

It turned out that the two plays each deal in their own way with the subject of mortality. Alan Bennett’s play is set in the geriatric ward of a local hospital threatened with closure, somewhere in the north of England, where the patients are in effect waiting to die. Ionesco’s takes place in an imaginary, surreal kingdom whose 483 year old monarch is told at the start of the play that he has just 90 minutes to live. Both plays are well produced and well acted, but curiously it was the surreal Ionesco, not the ironic Bennett, which I ultimately found the more moving.

Perhaps the reason for this is that Allelujah! slightly lacks focus. It has a cast of 23 and among them we see many familiar character types: apart from the dozen patients, we meet a self-satisfied local politician, a kindly doctor whose immigration status is uncertain, a briskly efficient (too efficient?) nurse, an opportunistic TV crew, a cynically ambitious management consultant, a lad on work experience. Their characters are deftly sketched in. The politician and TV crew are caricatures, more or less, but the others reveal unexpected aspects to their characters; you could imagine a TV series in which each in turn had their own story.

Perhaps the reason for this is that Allelujah! slightly lacks focus. It has a cast of 23 and among them we see many familiar character types: apart from the dozen patients, we meet a self-satisfied local politician, a kindly doctor whose immigration status is uncertain, a briskly efficient (too efficient?) nurse, an opportunistic TV crew, a cynically ambitious management consultant, a lad on work experience. Their characters are deftly sketched in. The politician and TV crew are caricatures, more or less, but the others reveal unexpected aspects to their characters; you could imagine a TV series in which each in turn had their own story.

As for the dozen patients, Bennett captures that mixture of distressing insight and sheer distress which the very old can display. In some their original personality has been erased; in others, distilled. They can say what they think, however cruel, however embarrassing it may be. This might have been exploitative but in Bennett’s perceptive hands is simple truth.

As for the dozen patients, Bennett captures that mixture of distressing insight and sheer distress which the very old can display. In some their original personality has been erased; in others, distilled. They can say what they think, however cruel, however embarrassing it may be. This might have been exploitative but in Bennett’s perceptive hands is simple truth.

Added to all this, one of the ward nurses has encouraged the patients to come together in a choir and we are given renditions of several classic songs, together with a little (deliberately) creaky dancing.  Nursing staff in care homes do sometimes encourage the residents in communal activities, but I doubt whether these activities often include song-and-dance routines, and I don’t feel they add all that much to the play. If they were intended purely for laughs it would be a bit cheap. In fact I think Bennett’s intention may be more subtle, to lighten a play whose satire might otherwise be too pointed and whose subject too grim for comfort, as if he can’t quite bring himself, or expect his audience, to confront them head-on. Whether you see this as lacking the courage of his convictions, or trying to eat his cake and still have it, I think it makes the play less coherent.

Nursing staff in care homes do sometimes encourage the residents in communal activities, but I doubt whether these activities often include song-and-dance routines, and I don’t feel they add all that much to the play. If they were intended purely for laughs it would be a bit cheap. In fact I think Bennett’s intention may be more subtle, to lighten a play whose satire might otherwise be too pointed and whose subject too grim for comfort, as if he can’t quite bring himself, or expect his audience, to confront them head-on. Whether you see this as lacking the courage of his convictions, or trying to eat his cake and still have it, I think it makes the play less coherent.

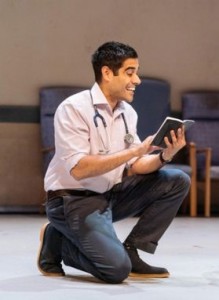

This is an ensemble piece with no star billing but good performances from the entire cast. I particularly liked Deborah Findlay as the ward sister and Sacha Dhawan as the doctor, who has the privilege in the final scene of breaking the fourth wall to address the audience directly. In that scene Bennett at last seems to speak clearly, with all the sardonic whimsy stripped away. The play is also very well directed by Nicholas Hytner, who has several other Bennett premières to his credit including The Madness of George III, The History Boys, The Habit of Art, and People, all at the National Theatre. I don’t think this is as strong a play as George III or The History Boys, but for a writer who is himself now 84 years old it is a clear sighted and far from mawkish piece of work, if a little lacking in edge.

This is an ensemble piece with no star billing but good performances from the entire cast. I particularly liked Deborah Findlay as the ward sister and Sacha Dhawan as the doctor, who has the privilege in the final scene of breaking the fourth wall to address the audience directly. In that scene Bennett at last seems to speak clearly, with all the sardonic whimsy stripped away. The play is also very well directed by Nicholas Hytner, who has several other Bennett premières to his credit including The Madness of George III, The History Boys, The Habit of Art, and People, all at the National Theatre. I don’t think this is as strong a play as George III or The History Boys, but for a writer who is himself now 84 years old it is a clear sighted and far from mawkish piece of work, if a little lacking in edge.

Exit the King is the first play by Ionesco every to be produced at the National Theatre. This seems to me shameful: he is a significant figure in the history of the European theatre, even if his star is, for the moment, in the eclipse. John and I have seen two other plays by him, both in 2007: Macbett, which we saw at Stratford-on-Avon, and Rhinoceros, which we saw at the Royal Court in London. I can no longer recall anything about Macbett, but we rather enjoyed Rhinoceros.

Ionesco is generally linked with the Theatre of the Absurd, though this seems to be a term more often used by critics than by authors: it extends from the nihilism of Beckett to the witty philosophising of early Stoppard, which makes it a bit of a catch-all. In Rhinoceros, the central concept is that people are gradually turning into rhinoceroses, and however absurd the idea there is clearly a point being made about conformity and fascism. It is also quite funny. Similarly, in Exit the King we are introduced to a king, his two queens, a doctor, a servant and a guard, who are apparently all that remain of what was once a kingdom. The king has defied death while his domains shrink and crumble around him; now at last, 483 years old, the time of his death is appointed, and we see him move in rapid sequence through the stages of denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance.

It’s interesting to read the comments on the Guardian blog about this play, with contributors sharply divided: some think the whole thing pretentious and, well, absurd, while others really enjoyed it. John and I are in the latter camp. If there is a problem with the play, it is that its initial tone belies its content; the absurd trappings suggest farce, and the extreme theatricality seems pretentious, though there are also some good verbal and visual jokes. But as the mood darkens the play takes shape and gathers weight, and its final scene is truly gripping.

Perhaps it would work less well with a lesser actor in the central role of King Bérenger. Here he is played by Rhys Ifans who takes even the greatest absurdities with seriousness and gives the role a monumental, Shakespearean weight. I thought he was matched, especially in that final scene, by Indira Varma as Queen Marguerite, who has throughout the play been the voice of chill warning, but now becomes an aspect of Charon as she leads her King over the threshold into death.

Perhaps it would work less well with a lesser actor in the central role of King Bérenger. Here he is played by Rhys Ifans who takes even the greatest absurdities with seriousness and gives the role a monumental, Shakespearean weight. I thought he was matched, especially in that final scene, by Indira Varma as Queen Marguerite, who has throughout the play been the voice of chill warning, but now becomes an aspect of Charon as she leads her King over the threshold into death.

The staging at this point is equally stunning. Until the last fifteen minutes of the play, the action has all taken place in front of what appears to be a solid wall in which are set, at varying heights, a number of windows and doors. Characters appear and disappear at these apertures in the manner of the Joke-Wall from television’s Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-in. (I suspect that this is an unintended resemblance; director Patrick Marber is not old enough to remember that show.) It seems a weak use of the Olivier Theatre’s stage resources.

The staging at this point is equally stunning. Until the last fifteen minutes of the play, the action has all taken place in front of what appears to be a solid wall in which are set, at varying heights, a number of windows and doors. Characters appear and disappear at these apertures in the manner of the Joke-Wall from television’s Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-in. (I suspect that this is an unintended resemblance; director Patrick Marber is not old enough to remember that show.) It seems a weak use of the Olivier Theatre’s stage resources.

Then, in the final scene, the wall starts cracking up. Parts slowly rise into the flies above the stage; others sink into the well below. Eventually nothing is left except a pathway like a red carpet leading from the front of stage into a far blackness, and Queen Marguerite first leads, then encourages, King Bérenger to pass along it.

The play was written in the early 1960s when Ionesco thought he was dying from liver disease. Eventually he recovered, and lived until 1994, though his later work is not so highly regarded. However Exit the King seems to me to transmute his thoughts and fears into art. It feels personal, and I found that final scene genuinely moving.

——————–

Ministry of Flat Walks 13 : Sedgwick

7 September 2018

To follow this walk on a map, open another tab on your browser and input this address: https://bit.ly/2x40EmT. John and I took this walk about a month ago, so my memory is not quite as fresh as it might be and some of my directions may not be precise. It is, however, an easy walk and flat almost all the way round, following the course of the River Kent and then the Lancaster Canal. Four miles at the most. We dawdled (especially when John was taking his photographs) and were finished in a little over two hours.

In the left centre of the map you can see the split-level roundabout where the A590 westwards to Barrow diverges from the A591 north to Windermere. Another, minor, road leaves this roundabout to the east and immediately bends southwards. On the outer side of this bend is a long lay-by where you can park your car. Just to the north from here, southeast of Sizergh Castle (a National Trust property with beautiful gardens) is Low Sizergh where there is a farm shop that John and I now visit regularly. It stocks John’s favourite beer plus a wide range of local produce including jams, cheeses, cakes and ice cream. Judging by the number of vehicles in the car park, we are not the only ones to find these wares attractive.

From your car, walk a short way along the road in the direction away from the roundabout and take the first left turn into another minor road with little motor traffic. On your right, some way below road level, is the River Kent. We have never seen the river really full here, but when it is in spate it must be quite a sight. The Kent flows down from the fells through the town of Kendal (just off the map to the north) and has been known to flood, most recently in December 2015 but also on at least three other occasions since 2000.

From your car, walk a short way along the road in the direction away from the roundabout and take the first left turn into another minor road with little motor traffic. On your right, some way below road level, is the River Kent. We have never seen the river really full here, but when it is in spate it must be quite a sight. The Kent flows down from the fells through the town of Kendal (just off the map to the north) and has been known to flood, most recently in December 2015 but also on at least three other occasions since 2000.

Walk along the minor road, past a turning to the left up to Low Sizergh. This side of the river is tree-lined, and separated from the road by a fence. About a quarter of a mile after the Sizergh turning, you will come to a suspension footbridge across the river.  John loves this bridge. At either end is a notice warning that a maximum of 25 people should use the bridge at any one time, but that should probably be fewer if they all behave as he does, jumping and up and down and deliberately causing the bridge to sway. Actually it looks, and no doubt is, quite solidly built. I can just remember as a boy being fascinated by a similar bridge at Betws-y-Coed in North Wales, which I could cause to sway slightly. But I had an excuse: I was eight years old at the time.

John loves this bridge. At either end is a notice warning that a maximum of 25 people should use the bridge at any one time, but that should probably be fewer if they all behave as he does, jumping and up and down and deliberately causing the bridge to sway. Actually it looks, and no doubt is, quite solidly built. I can just remember as a boy being fascinated by a similar bridge at Betws-y-Coed in North Wales, which I could cause to sway slightly. But I had an excuse: I was eight years old at the time.

Cross the footbridge and turn left, following the riverbank northwards. This part of the walk is not quite as picturesque as suggested by the map, being separated from the course of the river by a steep bank and a line of trees through which the water may only intermittently be seen. But if you are energetic enough you can scramble down to the water’s edge.

Cross the footbridge and turn left, following the riverbank northwards. This part of the walk is not quite as picturesque as suggested by the map, being separated from the course of the river by a steep bank and a line of trees through which the water may only intermittently be seen. But if you are energetic enough you can scramble down to the water’s edge.  The path is easy to follow, gravelled in places and hard-packed earth in others, and there are a couple of benches where you can take a break if you like.

The path is easy to follow, gravelled in places and hard-packed earth in others, and there are a couple of benches where you can take a break if you like.

After about three quarters of a mile, the track peters out and you have to cross a meadow, including a short, not especially stiff, climb. Your route then drops down to a minor road which runs west from Natland across the River Kent towards the village of Brigsteer (partially visible on the left of the map). Just to your left should be the picturesque bridge where this road crosses the river. You can get down to the riverside here if you want, and throw stones in the river like my brother.

Turn right into the minor road and follow it in the direction of Natland for no more than a couple of hundred yards. If you meet any motor vehicles I should be quite surprised. The road takes a left turn near a clump of farm buildings and goes over a shallow hump which is in fact a bridge over the now vanished Lancaster Canal. Just beyond on the right hand stile is a stile of that simple design which consists of a pair of vertically planted slates separated by a narrow gap through which you can squeeze but sheep, with any luck, will not. Go through the stile and down to the field below.

Turn right into the minor road and follow it in the direction of Natland for no more than a couple of hundred yards. If you meet any motor vehicles I should be quite surprised. The road takes a left turn near a clump of farm buildings and goes over a shallow hump which is in fact a bridge over the now vanished Lancaster Canal. Just beyond on the right hand stile is a stile of that simple design which consists of a pair of vertically planted slates separated by a narrow gap through which you can squeeze but sheep, with any luck, will not. Go through the stile and down to the field below.

You have arrived at the course of the Lancaster Canal. At one time the canal was planned to flow from Westhoughton near Wigan, where it would join the Leeds-Liverpool Canal, to Kendal, crossing the Rivers Ribble and Lune on aqueducts. However, the Ribble aqueduct was never completed, and the northern end of the canal was drained and filled in around the time of the Second World War, so the navigable section now stretches from Preston to Tewitfield, north of Carnforth. The Lune aqueduct still exists, a massive stone structure, and with its aid the canal is free of locks apart from two branches by which it is now connected to other waterways.

When you go through the stile you can just detect the route followed by the canal, as much as anything by its flatness, which contrasts with the gently sloping fields on either side. Apart from the bridge over which you have just crossed there is nothing left of the canal at this point; the channel has long since been filled in. However, the path is clear enough and you should follow it through the fields for about a mile and a half until you come to the village of Sedgwick. Along the way the line of the canal is visible in places and there are a few other tokens of its former existence, including a milepost standing forlornly in a meadow and a bridge, now completely isolated in the middle of a field, which was presumably built to enable the farmer and his livestock to cross from one side to the other.

When you go through the stile you can just detect the route followed by the canal, as much as anything by its flatness, which contrasts with the gently sloping fields on either side. Apart from the bridge over which you have just crossed there is nothing left of the canal at this point; the channel has long since been filled in. However, the path is clear enough and you should follow it through the fields for about a mile and a half until you come to the village of Sedgwick. Along the way the line of the canal is visible in places and there are a few other tokens of its former existence, including a milepost standing forlornly in a meadow and a bridge, now completely isolated in the middle of a field, which was presumably built to enable the farmer and his livestock to cross from one side to the other.

This is a really pleasant walk. There are a few stiles but none of them is difficult. The views are not spectacular, but there is open countryside all around, and you can if you are interested look out for the few remaining relics of the canal, mostly stonework of various kinds. However, when you get to Sedgwick you will find a most imposing relic, a stone aqueduct which bisects the village, crossing the road underneath. You can walk across the aqueduct if you like, follow the line of the canal a little further and turn right at another isolated bridge.  However, we preferred to climb down the steps into Sedgwick village so we could admire the aqueduct from below.

However, we preferred to climb down the steps into Sedgwick village so we could admire the aqueduct from below.

Apart from the aqueduct, which seems out of scale with its surroundings, Sedgwick is a fairly typical Cumbrian village, very grey with slate and stone buildings and walls, enlivened by the residents’ gardens. You should follow the road here down towards the River Kent, keeping Sedgwick House, now converted into apartments, on your left. This section of road is modrately busy, so take care. At the river, where a minor road diverges to the right, you should turn left, dropping down towards a road bridge over the Kent which you should cross and so return to your starting point.

Thanks to John for the excellent photographs, and for his patience when I ask him to illustrate a particular something.

——————–

Rail strikes

6 September 2018

For over two years now there have been intermittent strikes on several of Britain’s rail franchises, including two which I use regularly: Southern (which serves Oxted) and Northern (which serves Cark). The strikes are usually for 24 hour periods, with the clear aim of maximising disruption without too much impact on union members’ pay packets. Of course the impact of the strikes is also diluted. Many people I know simply work at home on strike days, and businesses have no doubt found ways to adapt.

For over two years now there have been intermittent strikes on several of Britain’s rail franchises, including two which I use regularly: Southern (which serves Oxted) and Northern (which serves Cark). The strikes are usually for 24 hour periods, with the clear aim of maximising disruption without too much impact on union members’ pay packets. Of course the impact of the strikes is also diluted. Many people I know simply work at home on strike days, and businesses have no doubt found ways to adapt.

There have been various complicating factors, but the underlying issue in these strikes is the same in each case. The operating companies, probably at the instigation of Government, want the opening and closing of train doors to be a duty of the driver. After some negotiation, the ASLEF union, which represents most of the drivers, has agreed. However, the RMT union, which represents train guards, wants this duty to remain with them. It is the RMT which is responsible for the continuing strikes.

The RMT has asserted that this is a matter of passenger safety. How can the train driver, from his position in the cab (which, for good reasons, he is not allowed to leave) be sure that the whole length of the “train despatch corridor” along the platform is clear, particularly in the dark, or for a train that may be up to 12 coaches long, or when the platform is crowded, or on a curve?

The RMT has asserted that this is a matter of passenger safety. How can the train driver, from his position in the cab (which, for good reasons, he is not allowed to leave) be sure that the whole length of the “train despatch corridor” along the platform is clear, particularly in the dark, or for a train that may be up to 12 coaches long, or when the platform is crowded, or on a curve?

These are all legitimate issues, but they are capable of practical solutions. Here is an interesting little report by HM Chief Inspector of Railways: https://bit.ly/2j7KIHD. Despite a small amount of technical jargon the underlying message is clear. The RMT’s assertion that “the report does not give driver-only operation a clean bill of health” is paper-thin. The independent Rail Safety and Standards Board, which draws up the official Rule Book for railway operation, has come to the same conclusions as HM Chief Inspector: https://bit.ly/2MXYtvF. As the RSSB shows, driver control of train doors has been standard practice on many London suburban services for 35 years without causing any concern.

The RMT’s safety argument is entirely specious. It was probably deployed in an effort to gain some public sympathy, and may have done so for a while, but as time has passed the effect has worn off. On Southern, for the last year, guards’ functions have been changed and their job title changed to train manager or on-board supervisor or some such. There has been no report of any increased risk to passengers and we would certainly have heard about it if there had been any incidents.

The effect has been that the RMT’s credibility has been undermined, not only with the general public but, I suspect, with its own members. Strike days are still regularly announced on Southern without any perceptible impact upon services, certainly not off-peak or in the evenings when I make my journeys. Timetable curtailments, which were introduced for a while, have now been withdrawn and the full service is being run. It would appear that RMT members on Southern have ceased to follow the union’s instructions.

I did wonder whether the RMT might be continuing its action on Southern in order to sustain the strike on Northern. If so, this would be secondary action, which is unlawful, so the RMT cannot admit it; but that would not make it untrue. And until quite recently the strikes on Northern seem to have been more effective. For a while there were no train services at all through Cark on strike days. (Bolshie Northerners!) But today I noticed in Grange-over-Sands station that a timetable has now been published for a revised service that will run on strike days. There are about half as many services as on a normal day, which shows there is still an impact; but the strike appears to be weakening here too.

It is not surprising that the RMT’s own members seem increasingly reluctant to support the strikes. Southern has made very public promises that none of the currently employed guards will lose their jobs or pay. Their duties have been redefined, but that is all. I do not know whether Northern has issued any similar guarantees, but it seems quite likely. Union members no doubt heeded the initial strike calls out of loyalty to their union, but as time has passed they must have realised that they are losing pay with no prospect of personal benefit. Guards are not badly paid, but their families will be feeling the pinch. The RMT cannot be surprised if fewer and fewer of its members are heeding its strike calls.

Of course the RMT has its reasons. Partly, I suspect, they are simply political. The union believes that it is the Government which has instigated the change in the role of guards; as a matter of principle, the Government must be opposed. But, more fundamentally, if guards lose their duty of closing train doors, that opens the way to driver-only operation of trains. And whether or not guards are retained as on-board supervisors, they are not actually a necessary part of the train crew. In that case the RMT loses most of its industrial muscle. It can call a strike and the trains still run. So I don’t think it fanciful to say that the RMT is fighting for its relevance. But it is still losing.

Of course the RMT has its reasons. Partly, I suspect, they are simply political. The union believes that it is the Government which has instigated the change in the role of guards; as a matter of principle, the Government must be opposed. But, more fundamentally, if guards lose their duty of closing train doors, that opens the way to driver-only operation of trains. And whether or not guards are retained as on-board supervisors, they are not actually a necessary part of the train crew. In that case the RMT loses most of its industrial muscle. It can call a strike and the trains still run. So I don’t think it fanciful to say that the RMT is fighting for its relevance. But it is still losing.

All the above can be observed, or read about, and understood. What I don’t really understand is why the RMT has been so confrontational. An alternative strategy might have been to work with the train companies, to show them that guards can be useful in other roles. Most obviously, revenue collection. Many stations are now unstaffed, which means tickets have to be purchased in advance or on the train. But not all guards are equally assiduous in this duty. Of my last four trips from Cark, an unstaffed station, I have only twice been asked for my ticket. Oxted has a ticket office, but other stations down the line are unstaffed off-peak, yet my ticket is checked perhaps one journey in four. Revenue is certainly being lost.

The union also had potential allies in the disabilities lobby which it has neglected. If there is no guard, at unstaffed stations there is no-one to help wheelchair-bound or otherwise disabled passengers to board or leave the train. I’m not sure this is even compliant with disabilities legislation, though I suppose some way must have been found to weasel out; it is certainly reprehensible. Why did the RMT not develop a joint campaign? It might well have been more effective, and harder to rebut, than the specious safety arguments.

The union might also have made more use of the public belief that the presence of guards adds a measure of security, particularly in the evenings. Guards need not be expected to put themselves in the way of terrorists or muggers, but they ought to be competent to deal with the rowdyism and drunkenness which many travellers fear. One advantage of this argument is that it is hard for any government, sensitive to public anxieties, to ignore. But, apart from bloggers on news websites, it is not much heard.

I suspect that insofar as the RMT has a strategy which goes beyond a simple reluctance to admit defeat, it is to hold out until the next election, when a change of government might bring new Ministers more sympathetic to the union’s cause. If Jeremy Corbyn becomes Prime Minister his union supporters may be looking for some payback. One way or another, they may be disappointed. ——————–

——————–

Macbeth at the RSC

5 September 2018

Coincidence is a funny thing. We notice when it happens, and don’t notice all the far more frequent times when it doesn’t. And when it does happen, we can find it hard to believe: is there some hidden plan at work?

Coincidence is a funny thing. We notice when it happens, and don’t notice all the far more frequent times when it doesn’t. And when it does happen, we can find it hard to believe: is there some hidden plan at work?

It is probably just a coincidence that the artistic directors of the National Theatre and the Royal Shakespeare Company decided to stage new productions of Macbeth within a few weeks of one another. They would surely not have chosen to compete so directly: at the margin they cannot have avoided stealing some of each other’s audience, since there must be many people quite keen to see the play but not to see it twice. Perhaps, say, eighteen months ago there was a meeting, perhaps a dinner party, at which Rufus Norris (NT) and Gregory Doran (RSC) got talking, as a result of which they were separately inspired to commission their new productions. Theatre is quite a small world; it’s not at all improbable that something like this might have happened.

Or perhaps there is a simpler explanation. Macbeth is commonly used as a set text for examinations. I remember studying the play myself while at school, and the first four lines of the great “Is this a dagger….?” speech have somehow stuck in my mind over the last fifty years. And set texts mean good business for playhouses.

Whatever the explanation, an opportunity was missed. Each production had a star name in a leading role: the RSC had Christopher Eccleston as Macbeth, the NT had Anne-Marie Duff for Lady Macbeth. Two actors who you would think perfectly suited to the roles, Eccleston as the man of action with a dark heart, Duff as the steel-willed embodiment of female ambition. They would surely have struck sparks off one another. As it is, we got two separate productions which never really catch fire.

I wrote on 19 July about the show at the NT, which owed more than a little to the tropes of horror movies. The RSC’s version, which John and I saw at Stratford-on-Avon a couple of weeks ago, is rather more conventional, largely in the RSC house style with a mostly bare stage. I’m afraid I thought it consistently uninspired, and the one or two original touches were unconvincing. There was not a single memorable scene to compare with the NT’s witches. The best words I can think of are competent and routine, well below the RSC’s usual standards.

The setting and costumes are generically modern-day. The aged Duncan comes on stage in a wheelchair; Macduff, wielding a briefcase. But we aren’t, I think, meant to perceive any specific contemporary references. This is probably just as well. I still have a memory of Patrick Stewart as Macbeth in a production which was given a rather too specific WWII-type setting that made no sense.

At least in that production Stewart himself was mesmerically good, moving through all the emotions demanded by the role: military pride, seduced by ambition which turns to cruelty, horror and eventually a doomed defiance. I had hoped for something similar from Eccleston; but I was disappointed. He gives a more conventional reading of the part than Rory Kinnear at the NT, which might please some people, but there is very little passion, and he is inclined to mumble. The RSC usually makes a point of ensuring that Shakespeare’s verse is clearly spoken; Eccleston, here, is a rare exception.

At least in that production Stewart himself was mesmerically good, moving through all the emotions demanded by the role: military pride, seduced by ambition which turns to cruelty, horror and eventually a doomed defiance. I had hoped for something similar from Eccleston; but I was disappointed. He gives a more conventional reading of the part than Rory Kinnear at the NT, which might please some people, but there is very little passion, and he is inclined to mumble. The RSC usually makes a point of ensuring that Shakespeare’s verse is clearly spoken; Eccleston, here, is a rare exception.

I had thought there was a danger that he would overwhelm his Lady Macbeth, Niamh Cusack, but in fact they are well matched: just not as dangerous as the characters demand. Cusack at least speaks the verse clearly but I didn’t get from her any sense of the character’s flintiness. She does play the panic of the banquet scene well, but can’t match up to Duff’s brilliance in the same scene. Cusack’s CV is impressive and varied, but I wonder whether Lady Macbeth may be a little outside her comfort zone.

I had thought there was a danger that he would overwhelm his Lady Macbeth, Niamh Cusack, but in fact they are well matched: just not as dangerous as the characters demand. Cusack at least speaks the verse clearly but I didn’t get from her any sense of the character’s flintiness. She does play the panic of the banquet scene well, but can’t match up to Duff’s brilliance in the same scene. Cusack’s CV is impressive and varied, but I wonder whether Lady Macbeth may be a little outside her comfort zone.

Any modern-dress production of Macbeth faces the problem of what to do about the witches. Here, director Polly Findlay has cast them as children, little girls dressed all in pink, each carrying her own tiny doll. This appears to be another horror movie trope, but I don’t know which movie. Someone suggested Carrie, but I don’t think that’s right. Answers on a postcard please…

I’ve mentioned previously that the RSC seems to have a blind spot with its coaching of child actors, but for this particular purpose their stilted, artificial speech adds an acceptable weirdness. Perhaps the children are intended as an image of the Macbeths’ childlessness; but if so that makes them a kind of mixed (visual) metaphor, and doesn’t explain, either, how Banquo also comes to see them. In any event I don’t think it works. Whatever the subtext, it is the witches’ prophecies which inflame Macbeth’s ambition and ultimately cause his downfall. These little girls simply cannot bear that dramatic weight.

I’ve mentioned previously that the RSC seems to have a blind spot with its coaching of child actors, but for this particular purpose their stilted, artificial speech adds an acceptable weirdness. Perhaps the children are intended as an image of the Macbeths’ childlessness; but if so that makes them a kind of mixed (visual) metaphor, and doesn’t explain, either, how Banquo also comes to see them. In any event I don’t think it works. Whatever the subtext, it is the witches’ prophecies which inflame Macbeth’s ambition and ultimately cause his downfall. These little girls simply cannot bear that dramatic weight.

Other concepts in this production similarly misfire. When Duncan is killed, a digital clock is hoisted above centre stage, and counts inexorably down to the moment of Macbeth’s death. I admire the actors’ discipline and timing, but really, what is the point? Key phrases from the text (such as “what’s done cannot be undone”) are projected on to an upstage screen, as if we need our hands held to steer us through the story. That seems vaguely insulting.

Played by Michael Houghton, the Porter is given a much greater role, appearing at the side of the stage throughout the play, occasionally on stage (as in the famous scene when there is a hammering at the castle gates while Duncan is being murdered) but more often as a kind of silent chorus. Or is he keeping score? Michael Billington, in his review in the Guardian, suggests that we are being invited to see the whole proceedings from the Porter’s perspective; but to me it seems like another rootless idea, remote from any consistent reading of the play as a whole.

Played by Michael Houghton, the Porter is given a much greater role, appearing at the side of the stage throughout the play, occasionally on stage (as in the famous scene when there is a hammering at the castle gates while Duncan is being murdered) but more often as a kind of silent chorus. Or is he keeping score? Michael Billington, in his review in the Guardian, suggests that we are being invited to see the whole proceedings from the Porter’s perspective; but to me it seems like another rootless idea, remote from any consistent reading of the play as a whole.

One feature which I did like was the reinvention of Macduff (very well played by Edward Bennett) as a bureaucrat. A difficulty in the original play is that when Macduff joins Malcolm in England, he leaves his wife and children unprotected. From Shakespeare’s point of view this facilitates the dreadful scene when Macbeth’s henchmen murder the wife and children; but Macduff’s action is hard to explain. Polly Findlay imagines him as a dutiful civil servant who suddenly comes to the realisation that he is serving a dangerous criminal regime; it has become his paramount duty, whatever the personal risks, to oppose that regime. Germany in the 1930s? The White House under Trump? These parallels are in no way suggested by the production, but to me at least they make sense.

One feature which I did like was the reinvention of Macduff (very well played by Edward Bennett) as a bureaucrat. A difficulty in the original play is that when Macduff joins Malcolm in England, he leaves his wife and children unprotected. From Shakespeare’s point of view this facilitates the dreadful scene when Macbeth’s henchmen murder the wife and children; but Macduff’s action is hard to explain. Polly Findlay imagines him as a dutiful civil servant who suddenly comes to the realisation that he is serving a dangerous criminal regime; it has become his paramount duty, whatever the personal risks, to oppose that regime. Germany in the 1930s? The White House under Trump? These parallels are in no way suggested by the production, but to me at least they make sense.

For all its faults, Rufus Norris’s production at the National offers a consistent vision of the play. That is what Polly Findlay’s version seems to lack. I could swallow the countdown, and the surtitles, and the pink child witches, and the ubiquitous Porter, if they served some wider vision; but they don’t. I enjoyed our afternoon at the theatre, but I was disappointed too. Macbeth is a great play, and will survive pretty much whatever you throw at it. But it deserves better than this somewhat passionless mishmash.