Troilus and Cressida

31 October 2018

Last weekend John and I, with Chris and Janet, went to see the RSC’s current production of Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida, playing in the main theatre at Stratford-on-Avon. It was only the second time I had seen the play. The first time was a positively dire production in 2006, appallingly directed by Peter Stein, that Stratford had imported from the Edinburgh Festival. Stein is better known for his work in opera, a genre well known for indulging its directors’ wild fancies, and had obviously been similarly indulged by the Festival. They should have known better. Anyway, I have wiped that one from my mind so far as possible. So I came to the play afresh.

Last weekend John and I, with Chris and Janet, went to see the RSC’s current production of Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida, playing in the main theatre at Stratford-on-Avon. It was only the second time I had seen the play. The first time was a positively dire production in 2006, appallingly directed by Peter Stein, that Stratford had imported from the Edinburgh Festival. Stein is better known for his work in opera, a genre well known for indulging its directors’ wild fancies, and had obviously been similarly indulged by the Festival. They should have known better. Anyway, I have wiped that one from my mind so far as possible. So I came to the play afresh.

It’s an odd, unclassifiable play, by turns comic, tragic, romantic (not much of that) and satirical. Modern audiences may not be unduly troubled by this genre-crossing, which is a staple of many admired television dramas like Mad Men or Breaking Bad. But it has always puzzled Shakespearean scholars, and perhaps some directors too, who struggle to find an appropriate tone for their productions. Not all directors: according to the programme notes, the great John Barton, one of the RSC’s founding fathers, considered it his favourite of all the plays, precisely because of its ambiguity, and produced it three times during his tenure at Stratford.

I had high hopes for this production. William Walton wrote an opera on the same story (but not using Shakespeare’s words) which I much admire. The music is by turns romantic and dramatic, and the tragedy, when it comes, shows Cressida as a despairing victim of war, guilty not of inconstancy but only of losing faith and hope. I was looking forward to seeing how Walton’s treatment compares with Shakespeare’s. And I had confidence too in Gregory Doran as director of the play. Doran is the RSC’s current Artistic Director and has been responsible for several top-class productions, including The Tempest (see my blog on 20 July last year), a brilliant all-black Julius Caesar in 2012, and Antony and Cleopatra in 2006, with Patrick Stewart and Harriet Walter, which was possibly the best Shakespeare I have ever seen.

I had high hopes for this production. William Walton wrote an opera on the same story (but not using Shakespeare’s words) which I much admire. The music is by turns romantic and dramatic, and the tragedy, when it comes, shows Cressida as a despairing victim of war, guilty not of inconstancy but only of losing faith and hope. I was looking forward to seeing how Walton’s treatment compares with Shakespeare’s. And I had confidence too in Gregory Doran as director of the play. Doran is the RSC’s current Artistic Director and has been responsible for several top-class productions, including The Tempest (see my blog on 20 July last year), a brilliant all-black Julius Caesar in 2012, and Antony and Cleopatra in 2006, with Patrick Stewart and Harriet Walter, which was possibly the best Shakespeare I have ever seen.

Alas, I was disappointed. The show is a misfire. It’s nowhere near as bad as Peter Stein’s attempt, and it has some good points, but overall it is a wasted opportunity.

Alas, I was disappointed. The show is a misfire. It’s nowhere near as bad as Peter Stein’s attempt, and it has some good points, but overall it is a wasted opportunity.

For one thing Doran has chosen to apply 50:50 casting to the play, which means that several obviously male roles are taken by women. Last year I admired Tamsin Greig as Malvolia at the National Theatre (4 April) and Jackie Morrison and Martina Laird as the tribunes in Coriolanus (28 September). And the cross-casting in this production works well in some cases: Adjoa Andoh as the scheming Ulysses (right, above) and Sheila Reid as the ultra-cynical Thersites (right, below) are among the best things in the show. But Suzanne Bertish, in an absurd shock of grey hair, as the unyielding Greek war leader Agamemnon is ridiculous, and the best that can be said about Amanda Harris as Aeneas is that she is more or less anonymous.

(right, below) are among the best things in the show. But Suzanne Bertish, in an absurd shock of grey hair, as the unyielding Greek war leader Agamemnon is ridiculous, and the best that can be said about Amanda Harris as Aeneas is that she is more or less anonymous.

That’s the trouble with applying a strict 50:50 rule; you end up with nonsenses. In an interview last year (https://bit.ly/2PuzctJ) Doran showed that he understood this, so it is doubly disappointing that he has not followed his own sensible advice.

But the 50:50 rule is not all that is wrong with the casting here. Unfortunately the lovers are weakly played. Granted that Troilus is not an especially heroic figure, Gavin Fowler is underpowered in the role and fails to project his lines clearly. And Amber James as Cressida is far too bland, failing to answer one of the play’s central questions: when she yields to the Greek Diomedes and forsakes her love of Troilus, is she a desperate woman (as William Walton makes her), or merely an inconstant one?

But the 50:50 rule is not all that is wrong with the casting here. Unfortunately the lovers are weakly played. Granted that Troilus is not an especially heroic figure, Gavin Fowler is underpowered in the role and fails to project his lines clearly. And Amber James as Cressida is far too bland, failing to answer one of the play’s central questions: when she yields to the Greek Diomedes and forsakes her love of Troilus, is she a desperate woman (as William Walton makes her), or merely an inconstant one?

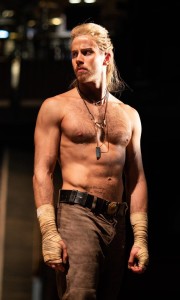

The play is only partly about Troilus and Cressida. It is, at least as much, about heroic but doomed Hector, the Trojans’ champion, and the Greeks’ increasingly desperate attempts to coax Achilles, who is sulking in his tent, out to face him. Among the warriors, the only one I found at all convincing was shaven headed Daniel Hawksford (right) as Hector. When he gives a speech rejecting the pleas of his wife Andromache and goes into battle because honour demands it, you know he is wrong, but it is true to his character.

The play is only partly about Troilus and Cressida. It is, at least as much, about heroic but doomed Hector, the Trojans’ champion, and the Greeks’ increasingly desperate attempts to coax Achilles, who is sulking in his tent, out to face him. Among the warriors, the only one I found at all convincing was shaven headed Daniel Hawksford (right) as Hector. When he gives a speech rejecting the pleas of his wife Andromache and goes into battle because honour demands it, you know he is wrong, but it is true to his character.

Most of the others are absurdly exaggerated. Shakespeare’s words make clear that Ajax is a vainglorious fool, but Theo Ogundipe’s performance in the role takes it to extremes, though at least he is good for a laugh. Andy Apollo (can that be his real name?) as Achilles sulks in his tent for most of the play, and then when his toy boy Patroclus is killed avenges him by an unheroic act of treachery (which I think must be Shakespeare’s invention; in Homer Achilles defeats Hector in single combat, though he dishonours the body afterwards).

It is the most shocking moment in the play. I can just about imagine the character that could give rise to these extremes, but I could not believe in this performance at all. Achilles may be sulky, but he’s also the Greeks’ finest warrior, better far than Ajax; you would never know that here.

It is the most shocking moment in the play. I can just about imagine the character that could give rise to these extremes, but I could not believe in this performance at all. Achilles may be sulky, but he’s also the Greeks’ finest warrior, better far than Ajax; you would never know that here.

The bridge between the two aspects of the play is Pandarus, very well played by RSC stalwart Oliver Ford Davies, who speaks the words clearly and characterises the role deftly.  Although Pandarus fits more into the lovers’ story than the warriors’, his archness is obviously intended to be satirically amusing, and the actor shows us how this can be done without the exaggeration that taints some of the other performances.

Although Pandarus fits more into the lovers’ story than the warriors’, his archness is obviously intended to be satirically amusing, and the actor shows us how this can be done without the exaggeration that taints some of the other performances.

As usual the play has been cut to make it acceptable in length to a modern audience. Perhaps inevitably this leaves various loose ends. One way and another I know the story well enough to recognise the characters of Cassandra (the prophetess, doomed never to be believed) and Calchas (the priest who is Cressida’s father, or in this production her mother), but I wonder what a less well informed audience member might have made of them. Calchas is an important figure in the story, as it is his/her intervention which causes Cressida to be handed over to the Greeks and thus forced to desert Troilus.

One aspect of the production which turned out better than I had feared was the music, which various reviewers have described as intrusive, but which I thought well judged and not at all overdone. The score is by Evelyn Glennie and is dominated by percussion (she is a notable percussion virtuoso), but it is used as theatrical music should be used, to underpin the action but not to overwhelm it. We have been to other productions this last year in which the music has been far more obtrusive than this. Perhaps it has been toned down in response to audience feedback.

It is possible to see Troilus and Cressida as a bitter satire on war – in fact that may be the best way to read the play. I wonder if Shakespeare had in mind the generations of conflict across Europe between Catholics and Protestants, which had caused endless waste as well as countless individual tragedies. In a still-divided England he would have had to dress up his moral lesson pretty thoroughly. And it is consistent with that to play the individual story as a romantic tragedy while the larger scene is given a more satirical twist. In this production, though, the tragedy is limply played and the satire, despite some good individual performances, is too close to out-and-out farce to have much bite. ——————–

——————–

Cup fever

30 October 2018

Last month, after I returned home from Cark I was too tired to do anything very active, and instead spent a couple of hours watching the BBC’s two-hour programme of highlights from the third (and final) day’s play in the Ryder Cup.

Last month, after I returned home from Cark I was too tired to do anything very active, and instead spent a couple of hours watching the BBC’s two-hour programme of highlights from the third (and final) day’s play in the Ryder Cup.

OK. New readers start here. The Ryder Cup is a golf contest played biennially between a team representing the USA and one representing the UK and Europe. A contest lasts three days and comprises 28 individual matches, with one point for a win and half a point for a tie (a “half” in golfing parlance). On the first two days, matches are between pairs of players – foursomes, in which each pair has a single ball and the players take alternate shots, and fourballs, in which each player has his own ball. On the third day there are 12 singles matches.

Originally the Cup was contested by the USA and the UK alone, and the matches were almost invariably, sometimes embarrassingly, one-sided in the USA’s favour. However, during the 1970s a new generation of European golf professionals emerged on the scene, led by the charismatic Seve Ballesteros. They were invited to join the UK in the Ryder Cup in 1979, and since then the match has been fiercely contested.

Originally the Cup was contested by the USA and the UK alone, and the matches were almost invariably, sometimes embarrassingly, one-sided in the USA’s favour. However, during the 1970s a new generation of European golf professionals emerged on the scene, led by the charismatic Seve Ballesteros. They were invited to join the UK in the Ryder Cup in 1979, and since then the match has been fiercely contested.

Most of the best golfers in the world, as measured by performance in tournaments, are Americans, but that seems to count for little in the Ryder Cup. The Americans have not won in Europe since 1993, while the Europeans have won in the States three times during that period. In this year’s match, played in France, the Americans made a strong start but were eventually outplayed and lost by 17½ points to 10½. Nonetheless, each time the Cup is contested the Europeans are regarded as underdogs. So even if you do not know much about golf it can be quite fun to watch the last day’s play as the plucky underdog may well triumph (hooray) and the arrogant favourites may well lose (double hooray).

No-one really knows why the Americans do not win every time. Some have suggested that the American players’ egos get in the way: they don’t feel themselves a team, as the Europeans do. Some think they are less comfortable with the matchplay format, in which each hole is contested separately, whereas almost all American tournaments are contested as strokeplay, that is the best score over four rounds. Some think the support given by European home crowds intimidates the Americans (that seems most unlikely to me). Some think the Americans lack motivation as the Ryder Cup is contested for glory, not dollars. Some think that the courses are set up differently, and Americans are less used to the European set-up, whereas Europeans play regularly in the States and so have more familiarity with American conditions. All I can see is that the Europeans invariably raise their game for the Ryder Cup, and the Americans, quite often, don’t.

No-one really knows why the Americans do not win every time. Some have suggested that the American players’ egos get in the way: they don’t feel themselves a team, as the Europeans do. Some think they are less comfortable with the matchplay format, in which each hole is contested separately, whereas almost all American tournaments are contested as strokeplay, that is the best score over four rounds. Some think the support given by European home crowds intimidates the Americans (that seems most unlikely to me). Some think the Americans lack motivation as the Ryder Cup is contested for glory, not dollars. Some think that the courses are set up differently, and Americans are less used to the European set-up, whereas Europeans play regularly in the States and so have more familiarity with American conditions. All I can see is that the Europeans invariably raise their game for the Ryder Cup, and the Americans, quite often, don’t.

Ryder Cup matches are attended by massive crowds, but I do wonder how much of the play they manage to see. You can take a place in the stands and watch each match play the hole where you are waiting, or you can choose to follow a single match around the course and hope to find adequate spots among the crowds along the way from which to watch. Neither seems very satisfactory to me. Golf fares much better on television with cameras all around the course, a skilful producer to switch scenes from one match to the next depending on state of play, and knowledgeable commentators who can explain the technicalities.

Ryder Cup matches are attended by massive crowds, but I do wonder how much of the play they manage to see. You can take a place in the stands and watch each match play the hole where you are waiting, or you can choose to follow a single match around the course and hope to find adequate spots among the crowds along the way from which to watch. Neither seems very satisfactory to me. Golf fares much better on television with cameras all around the course, a skilful producer to switch scenes from one match to the next depending on state of play, and knowledgeable commentators who can explain the technicalities.

BBC television used to be good at golf, broadcasting from the Open Championship and sometimes from other tournaments as well as the Ryder Cup. But, like many other sports, golf has succumbed to the lure of the money offered by Sky television, and Ryder Cup highlights are all that is now left on the BBC. Golf has always been an elite sport, as the equipment is expensive and golf club memberships more so, and is thus less reliant on mass participation; but just the same I wonder whether in the long run it will rue the lack of television exposure in terms of recruiting new generations to the game. Perhaps in twenty years’ time we will be bewailing Ryder Cup failures and attributing them to a paucity of talented young players as so many have failed to be exposed to the game at a formative age. Just as is now happening in cricket.

At various times I have toyed with the idea of taking up the game. Dad loved golf. He was a member at Formby Golf Club for more than thirty years and played at least weekly, more often if he could (and if Mum could spare him). I did play a couple of rounds with him, not at Formby where I would have been an embarrassment to him but on the municipal course at Allerton in Liverpool and once at Ulverston Golf Club. But somehow it didn’t quite grab me, I suspect because golf can be so humiliating. There is the ball, standing quite still on the grass in front of you. All you have to do is to hit it. Yet when you swing the club it is quite easy to miss the ball altogether, or to hit it so it trickles away just a few yards, or in the wrong direction. The first tee, where there are usually other groups of players looking on while they wait their turn, is particularly agonising.

At various times I have toyed with the idea of taking up the game. Dad loved golf. He was a member at Formby Golf Club for more than thirty years and played at least weekly, more often if he could (and if Mum could spare him). I did play a couple of rounds with him, not at Formby where I would have been an embarrassment to him but on the municipal course at Allerton in Liverpool and once at Ulverston Golf Club. But somehow it didn’t quite grab me, I suspect because golf can be so humiliating. There is the ball, standing quite still on the grass in front of you. All you have to do is to hit it. Yet when you swing the club it is quite easy to miss the ball altogether, or to hit it so it trickles away just a few yards, or in the wrong direction. The first tee, where there are usually other groups of players looking on while they wait their turn, is particularly agonising.

I also found it quite difficult to bring myself to play fairway shots effectively. In order to strike the ball cleanly, you have to aim the edge of your club to hit the bottom of the ball, which in practice means you have to hit into the turf just behind the ball and scoop away a large divot. I could never get the hang of this. As for hitting the ball with the rapid elevation required to get out of a bunker, forget it. I could easily spend hours in a single bunker and never get the ball out.

I also found it quite difficult to bring myself to play fairway shots effectively. In order to strike the ball cleanly, you have to aim the edge of your club to hit the bottom of the ball, which in practice means you have to hit into the turf just behind the ball and scoop away a large divot. I could never get the hang of this. As for hitting the ball with the rapid elevation required to get out of a bunker, forget it. I could easily spend hours in a single bunker and never get the ball out.

But I did enjoy walking round Formby with Dad and his golfing partners, some of whom I got to know quite well. Mark Twain reputedly once described golf as “a good walk spoiled.” I don’t know about spoiled, since Dad certainly enjoyed the game and would never have gone walking round Formby otherwise, but it’s true that the game is only part of the pleasure. At club level, at least, it is also about companionship, which you share with the other players as you walk around, and which Dad and his friends were good enough to share with me. So when I watch golf on the television, part of the pleasure is nostalgia.

This companionship notoriously extends to the nineteenth hole, that is, the bar in the clubhouse where players can enjoy a drink (or three) after their round is complete. I shared in that too, though the conversation often veered towards people that I didn’t know and events I could only guess at. Politics was rarely, if ever, mentioned, but it was a standing joke in the family that, but comparison with other golf club members, Dad was a dangerous radical.

This companionship notoriously extends to the nineteenth hole, that is, the bar in the clubhouse where players can enjoy a drink (or three) after their round is complete. I shared in that too, though the conversation often veered towards people that I didn’t know and events I could only guess at. Politics was rarely, if ever, mentioned, but it was a standing joke in the family that, but comparison with other golf club members, Dad was a dangerous radical.

When I started this blog I thought the only hole I could remember at Formby was the short 16th, which Dad used to fret about; he jokingly said that when he died he wanted his ashes scattered in the bunker there. We didn’t carry out that wish (though his colleague and golfing partner David Ramsdale did offer to arrange it for us). But looking at the Formby Golf Club website I find a picture gallery which brings back many more memories of the different holes, and of the clubhouse too. There are things in life we don’t realise we miss until we are reminded of them. I miss walking around Formby golf course with Dad.