Emergency service

30 November 2018

Yesterday I travelled up, by train, to Cark from Oxted. I nearly always make this journey by train; it normally takes five hours. The distance by road is almost exactly 300 miles, and though in principle you could manage to drive, mostly on motorway, in roughly the same time as the train, that is without allowing for refreshment stops or heavy traffic. Six hours would be a better estimate. The train is also cheaper, thanks to my Senior Citizen’s Railcard which knocks one third off the total fare: £75.25 return as opposed to £86 in petrol, plus wear and tear on vehicle and driver. As the station at Oxted is within 5 minutes of my home, and at Cark our house is literally just across the road from the station, convenience barely comes into the equation.

Yesterday I travelled up, by train, to Cark from Oxted. I nearly always make this journey by train; it normally takes five hours. The distance by road is almost exactly 300 miles, and though in principle you could manage to drive, mostly on motorway, in roughly the same time as the train, that is without allowing for refreshment stops or heavy traffic. Six hours would be a better estimate. The train is also cheaper, thanks to my Senior Citizen’s Railcard which knocks one third off the total fare: £75.25 return as opposed to £86 in petrol, plus wear and tear on vehicle and driver. As the station at Oxted is within 5 minutes of my home, and at Cark our house is literally just across the road from the station, convenience barely comes into the equation.

But that is on a normal day. Yesterday was not normal.

The first thing that went wrong was that I forgot my railcard, which I realised when I reached Oxted station. I had to go back home to collect it. That caused me to miss my planned train from Oxted, but for a £30 difference in fare was worth the extra delay. The next train from Oxted was half an hour later and it would be touch and go whether I could get across town to London Euston station in time to catch the 11.30 to Lancaster; but so be it.

When I eventually reached Euston I realised I needn’t have worried. All the mainline trains heading north were delayed and, though it was already past half past eleven, the 11.30 departure had not yet even been announced. There had been weather warnings earlier in the week, so I wasn’t entirely surprised. High winds were forecast, and that is bad news for railways where electric power is provided by overhead catenaries, as is the case on the West Coast Main Line between London and Lancaster. In these conditions Network Rail imposes speed restrictions so as to reduce the risk of swaying catenaries being torn down by a passing train.

When I eventually reached Euston I realised I needn’t have worried. All the mainline trains heading north were delayed and, though it was already past half past eleven, the 11.30 departure had not yet even been announced. There had been weather warnings earlier in the week, so I wasn’t entirely surprised. High winds were forecast, and that is bad news for railways where electric power is provided by overhead catenaries, as is the case on the West Coast Main Line between London and Lancaster. In these conditions Network Rail imposes speed restrictions so as to reduce the risk of swaying catenaries being torn down by a passing train.

Just the same, the amount of disruption seemed out of proportion to the severity of the weather: winds of 50 mph (as per the forecast) are not all that unusual in the winter.  However, Euston’s Twitter account (!) has reported today that the problem was not the wind in itself, but a piece of corrugated iron roofing that had been blown by an unusually strong gust on to the tracks at Leighton Buzzard. A photograph (left) was provided as evidence. Perhaps I should allow the railway operators a pass on this one.

However, Euston’s Twitter account (!) has reported today that the problem was not the wind in itself, but a piece of corrugated iron roofing that had been blown by an unusually strong gust on to the tracks at Leighton Buzzard. A photograph (left) was provided as evidence. Perhaps I should allow the railway operators a pass on this one.

At Euston, I had time to buy lunch to eat on the train and return to the crowds on the concourse waiting for their trains to be announced. I was quite worried by the crowds. The trains are not often full, and I usually manage to be one of the first passengers on to the platform. But when the service is disrupted, all bets are off. A couple of years ago I had a problem with the ticket machines at Oxted station, which resulted in my having to pay twice (though I did get the money back eventually), and so I now buy my ticket when starting the journey, which means I do not have a seat reservation and the risk of being left without a seat is a little higher.

Crowds on the concourse aren’t unusual. Either Virgin Rail or Network Rail, or possibly both of them in an unholy alliance, have adopted a policy of not allowing passengers on to the trains until about 10 minutes before departure time. I suspect this is one of the many little ways in which the railway is run to suit its operators, rather than its passengers. I know that the Pendolino express trains are in constant use (sweating the assets, in management-speak), but they are certainly standing at the platforms a good deal more than 10 minutes before due departure.

So at Euston you have to keep your eye on the departure board (risking a cricked neck in the process) and be ready to head off down to your platform as soon as it is revealed. The announcement over the station tannoy invariably comes after the board has changed. If you are quick, you may be able to avoid the scrum which develops as the passengers funnel down the ramp to the platform.

You may even be able to get one of the better seats, though this has become more difficult recently, again I think to suit the operator rather than the passengers. It used to be the case that one full carriage was set aside for unreserved seating. But in the last few months Virgin have changed this so that the unreserved seating is now provided in the buffet car which has only two-thirds as many seats.

Some Pendolino train sets have 11 carriages, some have only 9. You might think Virgin would ensure that the longer sets, which have an extra unreserved carriage, should be rostered to operate the more heavily used services, but so far as I can tell that doesn’t happen at all: you are as lilkely to get 11 carriages as 9 on the Manchester trains which run every 20 minutes and are rarely more than half full, but only 9 carriages rather than 11 on the Glasgow via Lancaster trains which run every hour and are always heavily loaded.

Some Pendolino train sets have 11 carriages, some have only 9. You might think Virgin would ensure that the longer sets, which have an extra unreserved carriage, should be rostered to operate the more heavily used services, but so far as I can tell that doesn’t happen at all: you are as lilkely to get 11 carriages as 9 on the Manchester trains which run every 20 minutes and are rarely more than half full, but only 9 carriages rather than 11 on the Glasgow via Lancaster trains which run every hour and are always heavily loaded.

Yesterday’s train had 9 coaches. I managed to get down to the platform soon enough to get a seat, but the unreserved carriage was crowded. The train eventually departed 35 minutes late and proceeded north, stately rather than swift because of the temporary speed restriction imposed (the passengers were told) because of the wind. By the time the speed restriction was lifted, we were running an hour late.

There was then a further delay of about 15 minutes at Preston, where there is always a crew change. I suspect the replacement crew hadn’t yet arrived. When the train eventually left Preston we were told it was no longer the 11.30, or the 12.30, from Euston but an “emergency service.” That means it was following an improvised timetable hastily put in place to make the best of a bad job. I suspect it was also a way of weaselling out from Virgin’s obligations under its franchise agreement: if the train is an emergency service then it probably means that franchise obligations are deemed to have been superseded by force majeure. Not that this matters much to the passengers, who just want to get to their destination in as near to good order as can be managed.

So I arrived at Lancaster too late to connect either with the 14.02 or the 15.03 service to Barrow. I, and several other passengers, had to wait until the 16.15. It was particularly galling that, although the platform for the train was being shown on the departure boards and the train was standing in the platform, it was unlit and the doors were closed. We were not allowed on board until about ten minutes before the departure time, when the train crew rolled up. I eventually arrived into Cark at about a quarter past five after a journey of seven hours.

So I arrived at Lancaster too late to connect either with the 14.02 or the 15.03 service to Barrow. I, and several other passengers, had to wait until the 16.15. It was particularly galling that, although the platform for the train was being shown on the departure boards and the train was standing in the platform, it was unlit and the doors were closed. We were not allowed on board until about ten minutes before the departure time, when the train crew rolled up. I eventually arrived into Cark at about a quarter past five after a journey of seven hours.

You can read the franchise document yourself if you have the patience for it: https://bit.ly/2PJoBaq. There are 528 pages, but so far as I can see says nothing about when passengers are to be allowed on to waiting trains, or about how much of the seating should be unreserved. It does include an obligation to avoid the need for long-distance passengers to stand, but does not otherwise specify how the 11 and 9 coach trains are to be deployed. Perhaps that is fair enough, but Virgin’s approach to rostering does seem a bit odd.

——————–

——————–

Aftermath

27 November 2018

Quite a long time after, in this case. John and I went to this exhibition at the Tate Britain gallery back in late August. But it has taken a little while for my thoughts about it to crystallise. At my hand I have the exhibition catalogue, to help jog my memory.

Quite a long time after, in this case. John and I went to this exhibition at the Tate Britain gallery back in late August. But it has taken a little while for my thoughts about it to crystallise. At my hand I have the exhibition catalogue, to help jog my memory.

The subject of the exhibition was British, French and German art in the wake of World War One. Most of the exhibits were paintings, though there were also some prints, drawings and photographs, and a small number of sculptures. There wasn’t much on show that was beautiful or inspiring, but more that was striking. At the time I was a little disappointed, without quite being able to articulate why.

I didn’t dislike the exhibition, and I wasn’t bored by it (except by some of the drawings and sculpture, of which I have no appreciation whatever). But it didn’t quite fulfil my expectations. I think perhaps I was hoping for more expressionist paintings. The Phaidon art website has a good simple explanation of expressionism, with illustrations: https://bit.ly/2DQyJfb. It’s a style which seems to me both interesting and powerful, a bridge between realism and abstraction. Expressionism was certainly in vogue around the time of the Great War, and I had, perhaps naively, imagined that it as a style ideally suited to wartime and postwar paintings, giving the artist an opportunity to express their feelings and experience directly on canvas.

I should have known better. I know more about music history than I do about art, and any history of music would regard the early twentieth century as a turning point, when classical music splintered into a wide array of different styles. The shattering impact of the Great War certainly intensified this process. The exhibition suggested that a similar fracturing of style happened in art, as different artists responded to the impact of the war in different ways.

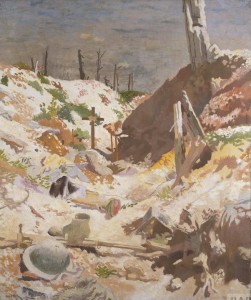

The first two rooms (out of eight) contained art that was actually created during the war, by officially appointed war artists and others. Some are quite good at evoking the horror of the battlefield, for instance CRW Nevinson’s Paths of Glory, which fell foul of the censors when it was first shown. Others attempt to do something similar, but less effectively. Look for instance at Charles Sims’ The Old German Front Line or William Orpen’s A Grave in a Trench, both of which I thought ill-focused and rather uninteresting.

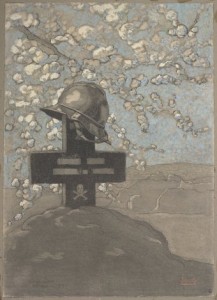

One or two contain images with a symbolism so obvious that they now seem almost trite, though no doubt they had considerable impact at the time: for instance Paul Jouve’s Grave of a Serbian Soldier or Orpen’s To the Unknown British Soldier in France, which was first completed in 1921 but still considered so shocking that Orpen had to repaint parts of it.

Most of these wartime paintings seem to me possibly valuable as historical documents but not very interesting as art. I might make an exception for Nevinson’s Ypres after the First Bombardment, but this isn’t a battlefield picture, and what I find most remarkable is how it anticipates Edmund Hopper (see my blog of 11 July 2018). The most interesting historical document in the show was not a painting at all but a short film by Lucien Le Saint, The First World War from Above, apparently shot from a dirigible balloon, showing the utter devastation of a French town near the front line. For documentary value it seemed to me to render the wartime artworks almost redundant.

One incidental benefit from the exhibition is that it has made me aware of Nevinson’s work. Here are two more of his paintings from the exhibition, He Gained a Fortune but he Gave a Son and The Soul of the Soulless City.

I had barely heard his name before this; he is not mentioned in any of my art encyclopedias. He seems to have been his own worst enemy. Wikipedia notes that “Nevinson’s boasting and exaggerated claims concerning his war experiences, together with his depressive and temperamental personality, made him many enemies in both the USA and Britain.” However that may be, the paintings are very striking and their range of style is remarkable. Input Nevinson Images into Google, and you will get a fuller idea.

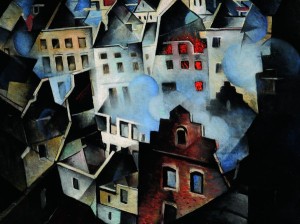

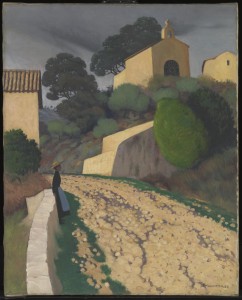

The rest of the exhibition consisted of postwar paintings broadly grouped by theme. In some a wartime influence was very apparent, as in the very striking War by Marcel Gromaire, another artist I had never heard of. In others you could scarcely see it at all, for instance Felix Vallotton’s Road at St Paul: he seems to have been taking lessons from Cézanne and to have ignored anything else since.

Actually that’s a bit unfair, as a quick look at Vallotton Images in Google will show, but it’s hard to see any wartime influence in his work. A few of the other paintings were flat-out peculiar, like Georg Schrimpf’s Swineherd. What’s that all about?

One group of paintings and drawings by German artists including Georg Grosz and Otto Dix had a very clear political message about postwar inequality and injustice. Most notable of these was Grosz’s Grey Day, which I think catches both the spirit and the style of many of these pictures, half way to being political cartoons.

However, the best of the work in the exhibition very clearly used wartime experience to create something more universal. Most striking of all of these was Winifred Knights’ The Deluge, which seems to me to have exactly this transformative quality, and to do so with a palate that is scarcely broader than Paths of Glory. Look closely, and you can see the wall of water that is about to engulf the figures in the picture.

For horror and pity, this far outdoes every piece of more explicitly wartime art in the show. It is a masterpiece. The Tate website has an article by poet Owen Sheers exploring his response to this painting: https://bit.ly/2AuTWb5. I also found a Guardian article about Knights (https://bit.ly/28XTwdI) which names her as a forgotten genius and reproduces more of her pictures. I regret not having seen the article when it was first published and, as a result, missing the exhibition last year to which it refers.

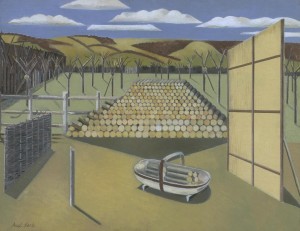

The war is equally near the surface in another picture exhibited here, Paul Nash’s Landscape at Iden. Is it just me, or is there a stylistic similarity with Knights? The subject matter could scarcely be more different… and yet, there is something unnaturally still about this scene with its bleached colours. Look at those logs, neatly cut and stacked. Could they perchance be bodies?

And finally, one other picture from the exhibition which further illustrates the fracturing of art after the war: Fernand Léger’s Discs in the City. If you didn’t know Léger’s biography you might find it difficult to discern any particular wartime influence on the painting. In fact he was mobilised as a soldier at the outbreak of war, nearly died in a mustard gas attack in 1916, and while convalescent painted the not-quite-abstract The Card Players, whose reinterpretation of human figures as metallic cones and cylinders appears to have been influenced by his wartime experience. The Card Players was not on show in Aftermath (rather a pity), but it is currently at the Tate Liverpool and will be there until next March. Perhaps we should plan a visit.

On reflection, I clearly got more out of Aftermath than I first realised. But the exhibition was undeniably patchy. In preparing this blog, I found a review in the Spectator magazine by its art critic Martin Gayford (https://bit.ly/2Q1Usbn). He sums up pretty accurately my own feelings.

All too often Aftermath is a jumble of the good, the bad and the indifferent… That’s the drawback of shows like this, which are fundamentally concerned with history rather than art. Sorrow and pity are no guarantee of artistic success.

——————–

The Future Starts Here

25 November 2018

A couple of weeks ago, I went with Michelle to the V&A Museum (for Australians: that’s the Victoria & Albert, but these days scarcely anyone uses the full name) to see this exhibition, The Future Starts Here. Actually the museum visit was really just an excuse for us to see each other, which we hadn’t done for several months. I gave Michelle her birthday present which was due in July. Afterwards we had a nice walk across St James’ Park and dinner at an old favourite, the Archduke wine bar near Waterloo. Nonetheless, we did at last pretend to look at the exhibits in the V&A. I also bought the catalogue.

A couple of weeks ago, I went with Michelle to the V&A Museum (for Australians: that’s the Victoria & Albert, but these days scarcely anyone uses the full name) to see this exhibition, The Future Starts Here. Actually the museum visit was really just an excuse for us to see each other, which we hadn’t done for several months. I gave Michelle her birthday present which was due in July. Afterwards we had a nice walk across St James’ Park and dinner at an old favourite, the Archduke wine bar near Waterloo. Nonetheless, we did at last pretend to look at the exhibits in the V&A. I also bought the catalogue.

I had been thinking of writing about the exhibition, but had somehow never got round to it, when I was prompted afresh by an article which appeared yesterday on the Guardian website (https://bit.ly/2FERwMN):  “Mars is lovely at this time of year.” This turned out to consist of four mini-essays by futurologists speculating about what life might look like in 2050.

“Mars is lovely at this time of year.” This turned out to consist of four mini-essays by futurologists speculating about what life might look like in 2050.

What exactly qualifies you to be considered a futurologist? I could write about the dubious credentials of at least two of the writers featured here, but I think it is more interesting to write about their predictions. They range widely from the quite interesting and plausible to the frankly outlandish. What I immediately notice, however, is how they totally ignore the most pressing scientific question of the age: climate change.

Perhaps they do not want to generate a pall of gloom. The Guardian already has its very own environmental pessimist, George Monbiot. But it isn’t necessary to view climate change only in gloomy terms. There is a wealth of science, actual and potential, around the mitigation of climate change and adaptation to its effects. To be fair, the Guardian article is clearly trying to paint a larger picture, not looking at specific innovations. But the absence of any reference to climate change is horribly blinkered.

The exhibition at the V&A is focused in the opposite direction, looking at specific innovations without much thought to a wider picture. It does at least have one climate-related exhibit, about the Great Green Wall, a project to create a mosaic of green, productive landscapes across North Africa (http://www.greatgreenwall.org). Apparently the project is already one-sixth complete: given its ambition you might think it should be better known. When complete it will be a true wonder of the modern world. However, the exhibit which most caught my eye was the very first, a simple robot arm carefully picking up a teatowel from a jumbled heap and placing it in an empty basket. Alongside is a video of a pair of similar arms in action except that they were picking up cloths of different sizes and folding them neatly before placing them in a pile. What this illustrates (I thought) was the difference between robot and human. A human eye quickly recognises a teatowel; a human hand treats it with appropriate but not excessive gentleness; eye and hands combine to fold it with adequate but not perfect neatness. The computer “eye,” on the other hand, takes time to recognise the item, and to find its corners, but the robot arms then fold it up very quickly and precisely.

However, the exhibit which most caught my eye was the very first, a simple robot arm carefully picking up a teatowel from a jumbled heap and placing it in an empty basket. Alongside is a video of a pair of similar arms in action except that they were picking up cloths of different sizes and folding them neatly before placing them in a pile. What this illustrates (I thought) was the difference between robot and human. A human eye quickly recognises a teatowel; a human hand treats it with appropriate but not excessive gentleness; eye and hands combine to fold it with adequate but not perfect neatness. The computer “eye,” on the other hand, takes time to recognise the item, and to find its corners, but the robot arms then fold it up very quickly and precisely.

In fact the development of artificial intelligence is a theme at the exhibition (insofar as it has any themes; many of the exhibits seemed to me somewhat randomly selected). AI is of course a recurring feature of popular fiction, and the threat of rogue AI has been a well-worn theme since HAL in the movie 2001. The robot arm, however, seemed to me to show just how far distant is a true AI from a human mind. It is certainly possible to construct computers to perform complex tasks, with or without the assistance of robotics. It is also now possible to construct computers to learn from their own experience: another exhibit is an AI playing a game of Breakout (a computer game from the early 1980s which involves knocking down a “wall”), and gradually learning a better strategy as it plays.

In fact the development of artificial intelligence is a theme at the exhibition (insofar as it has any themes; many of the exhibits seemed to me somewhat randomly selected). AI is of course a recurring feature of popular fiction, and the threat of rogue AI has been a well-worn theme since HAL in the movie 2001. The robot arm, however, seemed to me to show just how far distant is a true AI from a human mind. It is certainly possible to construct computers to perform complex tasks, with or without the assistance of robotics. It is also now possible to construct computers to learn from their own experience: another exhibit is an AI playing a game of Breakout (a computer game from the early 1980s which involves knocking down a “wall”), and gradually learning a better strategy as it plays.  But these functions are strictly in accordance with the computer’s programming. The ability to learn is itself programmed and circumscribed.

But these functions are strictly in accordance with the computer’s programming. The ability to learn is itself programmed and circumscribed.

Let me offer another example. A computer is programmed to play pinball, and to learn from its mistakes so it is able to achieve higher and higher scores, eventually surpassing the best human players. But it will never occur to the computer to kick or thump the pinball machine, like players in arcades regularly do, unless you programme it to think of this. All in all, I do not think we will see the rise of the robots in my lifetime, or yours.

One of the V&A’s exhibits is an (immobile) mock-up of a driverless car, branded Volkswagen who are one of the sponsors of the exhibition. What a giveaway. There has been quite a lot of talk recently about driverless vehicles, but that’s something else I don’t believe in, partly because of the difficulty of getting there from here. No doubt it will be possible in due course to develop an AI to control driverless vehicles which interact smoothly and efficiently with other such vehicles on road networks which have been engineered for the purpose. But as for operating in the same environment as careless, reckless, inattentive, ignorant human drivers – forget it. I would have been more interested to see an exhibit about developments in fuel technology, into which vehicle manufacturers have been putting a lot of research effort. Surely there must be some non-commercial secrets worth exhibiting.

Another popular theme which turns up both at the V&A and in the Guardian is the exploration of space. The exhibition seemed to me speculative almost to the point of fiction, consisting of models of possible future habitats on Moon or Mars. Frankly, you get better on Netflix. On the other hand, the Guardian article is at its best in the section by Neil deGrasse Tyson, director of a planetarium in New York, in which he speculates on the future of space exploration.

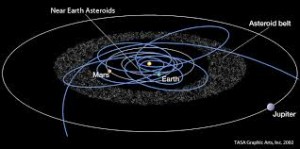

Inspired by the article, I have done a little research of my own. There are over 18,000 near-Earth asteroids. Of those, about 800 are currently thought to be at some risk of colliding with Earth within the next 100 years; most of them are very small. These asteroids represent a valuable potential source of scarce minerals. Tyson suggests that the next step in space exploration may be not a manned expedition to Mars but an ambitious commercial attempt to exploit those minerals, and I think I agree with him.

Inspired by the article, I have done a little research of my own. There are over 18,000 near-Earth asteroids. Of those, about 800 are currently thought to be at some risk of colliding with Earth within the next 100 years; most of them are very small. These asteroids represent a valuable potential source of scarce minerals. Tyson suggests that the next step in space exploration may be not a manned expedition to Mars but an ambitious commercial attempt to exploit those minerals, and I think I agree with him.

The final exhibits at the V&A are grouped together under the heading “Who wants to live forever?” Sounds promising. But by this stage Michelle and I were gasping for a cup of tea. Of course any public museum has to strike a balance between scholarship and accessibility, but the V&A seems to be erring towards condescension, and we both found it a little wearying. On a previous visit, a couple of years ago, I had felt that the museum had dumbed itself down; now I had the same feeling. Anyway, if there was anything worthwhile in this final group of exhibits, I’m afraid we missed it.

The Guardian writers tackle the same broad subject, but with more imagination than rigour. There are a few sensible observations. Yes, AI can help with differential diagnosis – it will mimic the process that doctors already follow. But it will not so easily replace the subtle skills of the best doctors, who hear what the patient doesn’t say, observe his behaviour and appearance, and exercise their bedside manner. Yes, gene therapy may well help to treat or prevent cancer and oher diseases. Yes, regrowth of damaged organs may become possible. But brain nets? Exowombs? Someone has been reading too much Aldous Huxley.

The Guardian writers tackle the same broad subject, but with more imagination than rigour. There are a few sensible observations. Yes, AI can help with differential diagnosis – it will mimic the process that doctors already follow. But it will not so easily replace the subtle skills of the best doctors, who hear what the patient doesn’t say, observe his behaviour and appearance, and exercise their bedside manner. Yes, gene therapy may well help to treat or prevent cancer and oher diseases. Yes, regrowth of damaged organs may become possible. But brain nets? Exowombs? Someone has been reading too much Aldous Huxley.

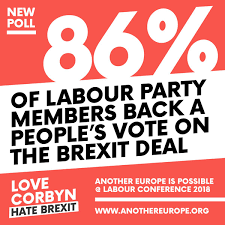

There is one subject, of which I suppose climate change might be considered to be an aspect, which is considered neither by the V&A nor by the Guardian, but which I stumbled over while looking up references and illustrations for this blog. Have a look at the Wiki entry for global catastrophic risk (https://bit.ly/1RdSHle), which has become a subject for serious scientific enquiry. My final illustration isn’t in the Wiki list, but it turned up when I put “global catastrophe” into Google and asked for images. Enough said.

Sorry for polluting the blog photo library. But the joke was too good to ignore.

Sorry for polluting the blog photo library. But the joke was too good to ignore.

——————–

Brexit

23 November 2018

I have until now refrained from writing here about Brexit, for several reasons. The story, full of twists and turns, is still evolving almost daily; whatever I write may be overtaken by events within days, even hours. And there are dozens of commentators in the media already mapping out its progress. John and I particularly like Andrew Rawnsley, who writes in the Observer every week. Even David, half a world away in Australia, has offered his twopennyworth (his blogs of November 2016 and November 2017). I have been reluctant to add to the clamour.

I have until now refrained from writing here about Brexit, for several reasons. The story, full of twists and turns, is still evolving almost daily; whatever I write may be overtaken by events within days, even hours. And there are dozens of commentators in the media already mapping out its progress. John and I particularly like Andrew Rawnsley, who writes in the Observer every week. Even David, half a world away in Australia, has offered his twopennyworth (his blogs of November 2016 and November 2017). I have been reluctant to add to the clamour.

When John and I talk, the subject of Brexit is barred, so much so that it has become a joke between us. But the truth is that he is deeply depressed by Brexit. Perhaps, as the youngest of us, he has the most reason. He cannot understand why I have remained so phlegmatic, since he knows that we share the same views.

I voted Remain in the referendum. I think the arguments over the loss of sovereignty are massively overstated; the sovereignty of nation states is overvalued and underpowered in the modern world. Brexiteers have dishonestly aroused fears over EU migration by conflating it with asylum seeking and economic migration from outside the EU; migration from the EU is good for our economy and has very little impact on the UK jobs market. I expect the UK will be worse off, economically and politically, if and when we leave.

I voted Remain in the referendum. I think the arguments over the loss of sovereignty are massively overstated; the sovereignty of nation states is overvalued and underpowered in the modern world. Brexiteers have dishonestly aroused fears over EU migration by conflating it with asylum seeking and economic migration from outside the EU; migration from the EU is good for our economy and has very little impact on the UK jobs market. I expect the UK will be worse off, economically and politically, if and when we leave.

The EU is not without its flaws. In recent years it has taken two serious wrong turnings that will take time and vision, or possibly crisis, to remedy. Its rapid expansion from nine members in 1973 and twelve in 1986 to 25 in 2004, in which year no fewer than 10 countries joined the Union, has not been matched by streamlined decision-making processes, so the organisation is now sclerotic and bureaucratised. The accessions were justified by post-Cold War politics: the EU wanted to help stabilise and modernise the former Iron Curtain nations, a worthy goal. But too little consideration was given to the practicalities.

The second wrong turning, entirely avoidable, was the introduction of the single currency, or more precisely its extension across almost the whole of the Union. In the UK we all owe a vote of thanks to Gordon Brown who kept us out of this folly. The single currency requires congruent economic policies for which a number of EU members were not ready. Its introduction has led directly to massive poverty in Greece, of which we should all be ashamed, and the threat of the same in other Mediterranean states. It underlies a dispute currently taking place between the EU and the right-wing government in Italy. Whichever way the dispute is resolved, it will be painful.

The second wrong turning, entirely avoidable, was the introduction of the single currency, or more precisely its extension across almost the whole of the Union. In the UK we all owe a vote of thanks to Gordon Brown who kept us out of this folly. The single currency requires congruent economic policies for which a number of EU members were not ready. Its introduction has led directly to massive poverty in Greece, of which we should all be ashamed, and the threat of the same in other Mediterranean states. It underlies a dispute currently taking place between the EU and the right-wing government in Italy. Whichever way the dispute is resolved, it will be painful.

It is arguable that there has also been a third strategic error. The preamble to the original 1957 treaty speaks of “closer union among the peoples of Europe, in which decisions are taken as openly as possible and as closely as possible to the citizen.” In context it is clear that this reflects the desire to promote mutual understanding as a bulwark against European war, which in 1957 was still a recent memory. Nothing is said about closer union of government. But over time politicians in the EU have come to reinterpret the phrase as an ambition to achieve a federal Europe, and have pushed towards that goal, well ahead of public opinion, let alone popular demand. This has poured fuel on the flames of anti-EU sentiment, not just in the UK.

Despite these flaws, I have faith in the EU. I am certain that it is a force for political moderation and economic prosperity. It has an increasingly impressive record in the protection of human rights, including employment rights, and of the environment. And it has achieved the fundamental goal of its founders, to secure a lasting peace. I am bewildered that Jeremy Corbyn continues to sit on the fence about Brexit. In his old-fashioned socialist’s heart of hearts he clearly believes that the EU is some kind of capitalist monster. If this is still his position when a general election is held, it will cost the Labour Party their best chance of power for a generation. He will be a class traitor.

Despite these flaws, I have faith in the EU. I am certain that it is a force for political moderation and economic prosperity. It has an increasingly impressive record in the protection of human rights, including employment rights, and of the environment. And it has achieved the fundamental goal of its founders, to secure a lasting peace. I am bewildered that Jeremy Corbyn continues to sit on the fence about Brexit. In his old-fashioned socialist’s heart of hearts he clearly believes that the EU is some kind of capitalist monster. If this is still his position when a general election is held, it will cost the Labour Party their best chance of power for a generation. He will be a class traitor.

However, my purpose in this blog is not to consider the current political scene, which anyway is in constant flux. My reasons for voting Remain were not just the EU’s economic benefits or its track record of achievement, but its capacity to address what I believe will be the primary challenges facing the world over the next fifty years:  climate change (and other environmental challenges), migration, and the increasing power of multinational corporations. What all of these have in common is that they are beyond the power of individual governments to control. The UK on its own will have next to no influence in these issues, but as a member of the EU it will be able to contribute. I do not want us to be sulking lonely in a corner while the grown-ups talk among themselves. I want us to have a voice, and the only realistic way we can do that is through the EU.

climate change (and other environmental challenges), migration, and the increasing power of multinational corporations. What all of these have in common is that they are beyond the power of individual governments to control. The UK on its own will have next to no influence in these issues, but as a member of the EU it will be able to contribute. I do not want us to be sulking lonely in a corner while the grown-ups talk among themselves. I want us to have a voice, and the only realistic way we can do that is through the EU.

It is a tragedy that the actual and prospective benefits of the EU have never been convincingly spelled out. The Project Fear strategy of the Remainers during the referendum campaign was deeply flawed. But for years before then, opponents of the EU had constantly dripped poison into public debate in the UK. Straight bananas, freeloaders on the NHS, job stealers, bloated bureaucrats: all these, and more, were grist to the mill. No matter that they were grotesque exaggerations or flat-out untruths. They were never effectively challenged or an alternative narrative established. We are now paying for that complacency.

Even if at the last minute we are somehow rescued from the folly of Brexit, these poisons will remain. It will take a generation for UK politics to be detoxified. Suppose that there is a second referendum, which this time votes Remain: it is idle to pretend that the Brexiteers will fold their tents and go meekly into history. Having once come so close to achieving their goal, they will redouble their efforts. We will never hear the last of them.

Even if at the last minute we are somehow rescued from the folly of Brexit, these poisons will remain. It will take a generation for UK politics to be detoxified. Suppose that there is a second referendum, which this time votes Remain: it is idle to pretend that the Brexiteers will fold their tents and go meekly into history. Having once come so close to achieving their goal, they will redouble their efforts. We will never hear the last of them.

The odds are still against a second referendum being called, but they are shortening all the time. If it happens, I shall vote Remain and hope for the best, because I think a slow detoxification, however uncomfortable, will do less damage than the purging which will occur if we leave. But it may be that a purging is what is needed. Shortages, weakened NHS, unemployment, redoubled austerity:  the impacts will be painful indeed, though I hope we will not quite be reduced to growing vegetables in our back gardens (sprouts, anyone? No wonder John is worried.) To begin with the EU will be blamed, or the Prime Minister for a botched Brexit deal, but soon enough the truth will dawn that we were better off in the EU than out.

the impacts will be painful indeed, though I hope we will not quite be reduced to growing vegetables in our back gardens (sprouts, anyone? No wonder John is worried.) To begin with the EU will be blamed, or the Prime Minister for a botched Brexit deal, but soon enough the truth will dawn that we were better off in the EU than out.

At that point I hope we will still have enough friends in the EU for our readmission to be speedily granted. I hope they tie us down more firmly next time so a future exit becomes unthinkable. I fear that there may be other stipulations: we will lose Margaret Thatcher’s “rebate” for sure, and may well be required to join the Euro. If the final consequence of Jacob Rees-Mogg’s Little Englander act is that sterling is abolished, it will be a fittingly ironic end.

The truth is that we are caught up in the middle of what future generations will regard as historic events, as significant as, say, the repeal of the Corn Laws. No-one chooses to live in tumultuous times (remember the old Chinese curse), but there is no point in being depressed about it. In future times, Britain taking its place in Europe will seem as inexorable a historical process as the Industrial Revolution or universal suffrage. Brexit will merely be a blip along the way.

In order to ensure that this blog is based securely on fact I have used various online resources. For the impact of EU migration, the Centre for European Policy Research online portal: https://bit.ly/2uMz7Iu. On the same subject, a report by the Financial Times on research by the Migration Advisory Committee: https://on.ft.com/2ML02bA. For the history of the EU’s growth, the European Commission website: https://bit.ly/2cnX6Dg. For “ever closer union,” the FullFact fact-checking website: https://bit.ly/2DUyS20. For analysis of the referendum results by age, sex, social class and education, the IpsosMori website: https://bit.ly/2zu1iMW.

In order to ensure that this blog is based securely on fact I have used various online resources. For the impact of EU migration, the Centre for European Policy Research online portal: https://bit.ly/2uMz7Iu. On the same subject, a report by the Financial Times on research by the Migration Advisory Committee: https://on.ft.com/2ML02bA. For the history of the EU’s growth, the European Commission website: https://bit.ly/2cnX6Dg. For “ever closer union,” the FullFact fact-checking website: https://bit.ly/2DUyS20. For analysis of the referendum results by age, sex, social class and education, the IpsosMori website: https://bit.ly/2zu1iMW.

——————–

Clash of Titans

21 November 2018

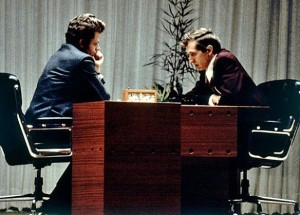

A couple of days ago, I happened to notice a link on the Guardian’s website to a story about the World Chess Championship match between the champion Magnus Carlsen and challenger Fabiano Caruana which is currently taking place in London. I have been following the match, in a slightly desultory way, since it began a couple of weeks ago. For each game the Guardian has provided a running commentary by a staff writer and a Youtube link to a live feed from a studio where three grandmasters are offering comments on the play.

A couple of days ago, I happened to notice a link on the Guardian’s website to a story about the World Chess Championship match between the champion Magnus Carlsen and challenger Fabiano Caruana which is currently taking place in London. I have been following the match, in a slightly desultory way, since it began a couple of weeks ago. For each game the Guardian has provided a running commentary by a staff writer and a Youtube link to a live feed from a studio where three grandmasters are offering comments on the play.

Chess has become more interesting again since its dominance by Russian grandmasters was definitively broken by Viswanathan Anand when he won a championship tournament in 2005. (The title is usually decided in a head-to-head match between champion and challenger; this was an exception.) Anand went on to defend his title three times before he was defeated by Carlsen in 2013. Carlsen has already successfully defended his title in two championship matches and, according to the complex algorithm used to determine the relative strength of chess players, he is currently the strongest player of all time.

So I clicked on the link, and was immediately hooked. The eighth game of the match was already in progress, the first seven having all been drawn. And Caruana, who had been slightly worse than Carlsen in the previous games, appeared to have a much superior position. Neither player had achieved an advantage in material (ie taken more of the opponent’s pieces), but Caruana seemed to have several attacking options, while Carlsen’s position was congested. Most of his pieces were blocked in with few useful moves available.

The position caught my eye. I switched on the live feed and was riveted to the screen for the next hour. For the next few moves Caruana continued to apply pressure; you could almost feel Carlsen squirming as he tried to find some counter-play. Then, out of the blue, Caruana made a weak move which allowed Carlsen completely off the hook. After an hour the game was drawn.

On the live commentary there was quite a lot of waffle (imagine Test Match Special when the covers are on the pitch and nothing is happening), but also some incisive analysis. The experts in the studio knew at once when Caruana made his fateful mistake, and gave a clear explanation of why it was the wrong move. The below-the-line comments by Guardian bloggers were also illuminating. It appears that Caruana is not rated too highly by the online community – as soon as the opening moves, memorised in advance, give way to mid-game complications, it is said that he slows down and becomes much more tentative. Carlsen on the other hand is admired for his ability in complex situations and his ability to grind out a win from slight advantages, but is thought to be lazy. Some bloggers suggest that he has not prepared for the match anything like so thoroughly, and is relying on his superior matchplay ability. I’m not smart enough, and haven’t been paying enough attention, to say whether any of these criticisms are valid, but it evidently makes for an interesting contrast between the players.

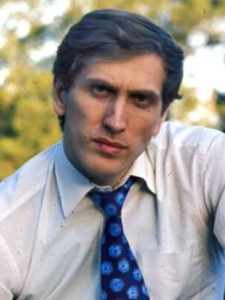

To find the last chess match which I followed with anything like the same degree of interest you have to go right back to the summer of 1972 when Bobby Fischer won the title from Boris Spassky. I remember that we spent the summer holiday that year up in the Lake District. I arranged to have a copy of the Times newspaper (those were pre-Murdoch days) delivered every day, so that I could follow the match. The paper was left for me in the mailbox by the crossroads just down the road.

To find the last chess match which I followed with anything like the same degree of interest you have to go right back to the summer of 1972 when Bobby Fischer won the title from Boris Spassky. I remember that we spent the summer holiday that year up in the Lake District. I arranged to have a copy of the Times newspaper (those were pre-Murdoch days) delivered every day, so that I could follow the match. The paper was left for me in the mailbox by the crossroads just down the road.

The match itself was an astonishing event. It took place in Rejkjavik at the height of the Cold War and put chess on the front pages; Fischer and Spassky became household names. Fischer was possibly the greatest chess genius ever. (The fact that Carlsen is now rated higher is misleading – the ratings are calculated by reference to players’ win/loss records and the strength of their opponents, and there is a slow but inexorable ratchet upwards.) But he was also completely paranoid about Russian conspiracies, and the story of the match is one of Fischer’s constant complaints, most of which seem to have had no basis in reality.

Fischer did have some reason to be suspicious. He had previously asserted that in the 1962 Candidates turnament, to determine who would be the challenger for the world championship in 1963, three of the five Soviet players had prearranged quick draws in their games against each other in order to conserve their energy for playing against Fischer. Chess historians now generally agree that this accusation is correct. However, there is no evidence of any malpractice at Rejkjavik in 1972.

Fischer did have some reason to be suspicious. He had previously asserted that in the 1962 Candidates turnament, to determine who would be the challenger for the world championship in 1963, three of the five Soviet players had prearranged quick draws in their games against each other in order to conserve their energy for playing against Fischer. Chess historians now generally agree that this accusation is correct. However, there is no evidence of any malpractice at Rejkjavik in 1972.

In those days the championship title was contested once every three years in a match of 24 separate games. So Fischer held the title until 1975, when he was due to meet the next great Russian chess grandmaster, Anatoly Karpov. That would have been a clash of the titans indeed, if it had ever happened. But it didn’t. Fischer had very strong and immovable views on the format for the match: he wanted there to be an unlimited number of games, all draws discounted, the winner being the first to win 10 games. Karpov wouldn’t sign up to this and the chess authorities agreed with him. Fischer refused to play and Karpov won the title by default.

Fischer’s desire to discount all draws had some merit. In the current match, Carlsen and Caruana have now drawn nine consecutive games, with three to go. If the match remains tied they will move on to rapid chess (25 minutes, plus 10 seconds for each completed move) per player, and then if necessary to blitz chess (5 minutes plus 3 seconds increment). Carlsen is a noted exponent of rapid and blitz; Caruana is not. So the run of draws suits Carlsen more than Caruana. Some chess players clearly think that it is wrong for the world championship to be decided in this way. It’s a bit like resolving a drawn Test series by playing T20.

But Fischer was his own worst enemy. His endless complaints and demands left him more or less friendless – still admired, revered even, but with no-one to take his part. He withdrew altogether from active play and became a recluse. When he eventually died in 2008 he was once more, outside the world of chess, virtually unknown.

But Fischer was his own worst enemy. His endless complaints and demands left him more or less friendless – still admired, revered even, but with no-one to take his part. He withdrew altogether from active play and became a recluse. When he eventually died in 2008 he was once more, outside the world of chess, virtually unknown.

A book about the 1972 match has been sitting on my bookshelves, unregarded, for years. Re-reading it now, I was transported back, not just to Rejkavik 1972 but to the days when I was still playing. At school the chess captain was David Evans, a very good player for a boy. I remember once playing a stubborn defence against him which he couldn’t break down. That was fun. However, there was another boy, David Lynch, who was not as good as David E but who beat me every time. Somehow I could never see through his plans. I know I played for the school team three or four times, but curiously I only remember one of them, when we went to Ormskirk on the train for a match and I won my game early.

At Oxford the story was similar. I played three or four times for the college, with outcomes which I have now completely forgotten. I also played in a tournament at the Oxford Union, beating Colin Maltby (father of Kate who has been in the news recently) in a positional game the first round, then losing in the second round against a player who used an old-fashioned gambit opening against me. That was very annoying.

However, what I most remember from that time is borrowing a copy of a chess handbook, Modern Chess Openings. I was fascinated, but also intimidated, by the range of possible openings and the depth (ie number of follow-up moves) to which they had been analysed. I realised that if I wanted to continue with chess I would have to study and memorise a lot of this stuff. It seemed more like work than play. Which is why, in the current match, my sympathies lie more with Carlsen than with Caruana.

——————–

Two half Measures

17 November 2018

The Donmar is a small studio theatre of just 250 seats, located in an old hops warehouse in London’s Seven Dials district, just north of Covent Garden. I have been a regular visitor since the RSC took over the theatre in 1977, soon after I first came to live in London. It was at the Donmar that I saw the RSC’s legendary production of Macbeth with Ian McKellen and Judi Dench. I only wish I could remember more about that show. I have a nasty suspicion that I may have dozed off.

The Donmar is a small studio theatre of just 250 seats, located in an old hops warehouse in London’s Seven Dials district, just north of Covent Garden. I have been a regular visitor since the RSC took over the theatre in 1977, soon after I first came to live in London. It was at the Donmar that I saw the RSC’s legendary production of Macbeth with Ian McKellen and Judi Dench. I only wish I could remember more about that show. I have a nasty suspicion that I may have dozed off.

In 1982 the RSC moved its London base to the Barbican Centre, and for the next few years the Donmar hosted a variety of ad hoc or touring productions. But in the early 1990s there were new owners and new investment which radically improved the facilities for performers and audiences alike. At the same time a permanent production company was formed, initially under the direction of Sam Mendes. He was succeeded in 2002 by Michael Grandage and in 2012 by Josie Rourke. Thanks to their efforts, tickets for Donmar productions are now among the most sought-after in all of London.

John and I have been regular visitors to the Donmar. Among the most memorable shows we have seen there was the classic Greek tragedy Hecuba, which we saw with Mum in 2004. There was a pool of water representing the sea at one side of the stage, and at the start of the play a previously unseen Eddie Redmayne, playing the ghost of Polydorus (Hecuba’s son), rose from the water. I don’t think we have ever seen a better, or more arresting, coup de théâtre at the start of any play. Redmayne, of course, has since become much more famous for his film roles.

We haven’t been to the Donmar quite so often recently, partly because tickets have been so difficult to obtain, and partly because under Josie Rourke the productions have become increasingly radical and (to us) unattractive. As a result we missed Rourke’s trilogy of Shakespeare plays with all-female casts, including Harriet Walter as a widely acclaimed Julius Caesar. I didn’t want to miss out again, and so for the Donmar’s current production of Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure, directed by Rourke herself, I booked seats well before the production opened.

When we read the reviews, we feared the worst. Apparently, instead of giving us the full play, Rourke had reshaped it into its bare essentials so that the play could be performed twice, once (before the interval) in traditional dress, and a second time (after the interval) in a modern setting with the gender of the protagonists, Isabella and Angelo, reversed. The intention, reportedly, was to bring out the play’s theme of sexual exploitation more starkly. We were afraid that we would be presented with some kind of right-on interpretation which converted Shakespeare’s ambiguous, troubling original into some kind of feminist tract. Still, I had bought the tickets. Better not waste them.

We needn’t have worried. True, the second-half repetition adds nothing and is just a bit tedious. It really makes no sense in a modern setting that Claudio is condemned to death, in accordance with the letter of the law, for having extramarital sex with his long-term girlfriend – an implausibility that the production treats, in the only possible way, as though it is nothing out of the ordinary.

But the repetition and anachronism don’t spoil the show, I think for two reasons. First, the text is exceptionally well edited. As noted in the Rough Guide to Shakespeare, “the scabrous humour of the play’s Viennese fleshpots… threatens to overwhelm the main business of the plot.” Not here. The sub-plots are winnowed out, allowing the size of the cast to be reduced and the principal themes to emerge more clearly. Long speeches are cut back and Elizabethan language is modified or omitted. Perhaps there is some loss in poetry, but the drama emerges very clearly and swiftly.

But the repetition and anachronism don’t spoil the show, I think for two reasons. First, the text is exceptionally well edited. As noted in the Rough Guide to Shakespeare, “the scabrous humour of the play’s Viennese fleshpots… threatens to overwhelm the main business of the plot.” Not here. The sub-plots are winnowed out, allowing the size of the cast to be reduced and the principal themes to emerge more clearly. Long speeches are cut back and Elizabethan language is modified or omitted. Perhaps there is some loss in poetry, but the drama emerges very clearly and swiftly.

One other minor loss may be that there is scarcely time for Isabella’s dilemma to sink in before the Duke arrives to sort things out. I don’t know the play well enough to be sure, but I had a distinct feeling that the scene where Isabella’s brother Claudio pleads with her to preserve his life, at the expense of her chastity, has been quite severely cut. It can and should be a harrowing moment, but here some of the effect may have been sacrificed. Of course in Shakespeare we know the outcome well in advance, but a good production will still develop dramatic tension; in this MfM it is largely missing. But this is offset by the gain in clarity. No-one in the audience, however unfamiliar with the play, could possibly miss its essential points.

Second, the protagonists Isabella and Angelo are brilliantly played by Hayley Atwell and Jack Lowden. I recognised Atwell from television but had quite forgotten that she was in an outstanding production of Arthur Miller’s A View from the Bridge which John and I saw a few years ago. I didn’t remember Lowden’s name at all, but in fact him, too, we had seen previously, in an equally fine production of Ibsen’s Ghosts, at the Almeida. Neither has much pedigree as a Shakespearean, but in this MtM they speak the sometimes knotty verse to the manner born.

Second, the protagonists Isabella and Angelo are brilliantly played by Hayley Atwell and Jack Lowden. I recognised Atwell from television but had quite forgotten that she was in an outstanding production of Arthur Miller’s A View from the Bridge which John and I saw a few years ago. I didn’t remember Lowden’s name at all, but in fact him, too, we had seen previously, in an equally fine production of Ibsen’s Ghosts, at the Almeida. Neither has much pedigree as a Shakespearean, but in this MtM they speak the sometimes knotty verse to the manner born.

And the one big advantage of the reversed roles is that we get to see Atwell’s and Lowden’s versatility. The transformation of Atwell, in particular, was sensational. As the novice Isabella she begins the play quiet and self-effacing, only to develop into a passionate defender of her rights over her own body. Then in the second half she becomes a cynical, sexually exploitative lawyer and is just as credible.

And the one big advantage of the reversed roles is that we get to see Atwell’s and Lowden’s versatility. The transformation of Atwell, in particular, was sensational. As the novice Isabella she begins the play quiet and self-effacing, only to develop into a passionate defender of her rights over her own body. Then in the second half she becomes a cynical, sexually exploitative lawyer and is just as credible.

Lowden similarly conveys the corruption of his character very effectively.  In particular, he matches Atwell point for point in the scene where Angelo bluntly tells Isabella that it is his word against hers, and he, not she, will be believed. At this point the contemporary echoes are unmistakable. Perhaps Lowden is not quite so convincing in the second half, but that may be because the whole premise is quite hard to swallow.

In particular, he matches Atwell point for point in the scene where Angelo bluntly tells Isabella that it is his word against hers, and he, not she, will be believed. At this point the contemporary echoes are unmistakable. Perhaps Lowden is not quite so convincing in the second half, but that may be because the whole premise is quite hard to swallow.

In fact John and I wondered whether Rourke’s original concept may have been to perform a stripped down version of the play, and that she added the second-half repetition only to satisfy playgoers who might very well not be happy with an MfM that lasted just seventy minutes. It’s hard to see that its themes emerge any more clearly: if anything, they are undercut by a second act in which the exploiter is a woman and the exploited a man. Perhaps the concept only emerged in early rehearsals and its pointlessness was obscured by the sheer brilliance of Atwell and Lowden in their reversed roles.

The third principal character in MfM is the Duke, played here by Nicholas Burns, who is better known for his wide ranging television work. Here he does nothing wrong but is rather outshone by Atwell and Lowden, and does not really succeed in making the manipulative Duke a credible figure. It’s easy enough to understand the Duke at the beginning of the play: he wants to re-establish the rule of law in Vienna without having to take the blame for it. But by the end it is the Duke who is pulling all the strings and who enforces something like a happy ending, or at least a resolution, with three couples married off in the traditional manner of a Shakespearean comedy – though only one of those couples, you imagine, will be truly happy at the outcome. What, exactly, has the Duke been playing at? Neither Rourke nor Burns really finds an answer.

The third principal character in MfM is the Duke, played here by Nicholas Burns, who is better known for his wide ranging television work. Here he does nothing wrong but is rather outshone by Atwell and Lowden, and does not really succeed in making the manipulative Duke a credible figure. It’s easy enough to understand the Duke at the beginning of the play: he wants to re-establish the rule of law in Vienna without having to take the blame for it. But by the end it is the Duke who is pulling all the strings and who enforces something like a happy ending, or at least a resolution, with three couples married off in the traditional manner of a Shakespearean comedy – though only one of those couples, you imagine, will be truly happy at the outcome. What, exactly, has the Duke been playing at? Neither Rourke nor Burns really finds an answer.

So the show has some weaknesses: an unnecessary second act, an underdeveloped Duke, a certain lack of dramatic tension. But overall this is an interesting production with two outstanding protagonists in which the play’s themes, not just of sexual exploitation but of law and morality, emerge very clearly.

——————–

A Star is Born

1 November 2018

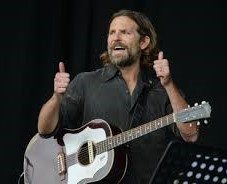

A few days ago Georgina and I went to see the movie A Star is Born at the Oxted Everyman cinema. This was not the original film from 1937, starring Fredric March and Janet Gaynor, nor the 1956 version (James Mason and Judy Garland), nor the one from 1976 (Kris Kristofferson and Barbra Streisand), but a brand-new 2018 version starring Bradley Cooper and pop icon Lady Gaga. Perhaps this movie would not have been at the top of my list, but I thought Georgina might like it, and it would be a nice change for us both. As it happens, I probably had a better time than she did.

A few days ago Georgina and I went to see the movie A Star is Born at the Oxted Everyman cinema. This was not the original film from 1937, starring Fredric March and Janet Gaynor, nor the 1956 version (James Mason and Judy Garland), nor the one from 1976 (Kris Kristofferson and Barbra Streisand), but a brand-new 2018 version starring Bradley Cooper and pop icon Lady Gaga. Perhaps this movie would not have been at the top of my list, but I thought Georgina might like it, and it would be a nice change for us both. As it happens, I probably had a better time than she did.

This was only the third time I had visited the cinema since it was refurbished last year, and the first time I had been in Screen 3, which turned out to be a studio cinema, with perhaps 50 seats in six or seven rows in front of a full-size screen. The seats are truly luxurious two-seater sofas with a little table on either side: patrons are encouraged to bring their drinks with them. About 300% more comfortable that the typical movie house. Goodness knows how Everyman are making any money from the deal. Perhaps the new multiplex layout (three separate screens showing three different movies), and the well-appointed café and bar at front of house which welcome passers-by as well as moviegoers, are enough to keep the show on the road.

So we settled into our sofa and waited to be entertained. Not without a degree of anticipation. Critics tend to be cruel about remakes, often with good reason, but this latest iteration of a familiar story has earned excellent reviews. Here for instance is the review by Mark Kermode for his Radio 5 show: https://bit.ly/2qsnvoV. I didn’t in fact see this until after I had seen the film, but I think he’s spot on in his assessment, and for good measure adds a few movie trivia that I didn’t previously know.

So, what can I add that Kermode has not already said? Well, just to repeat, both the leads are really good. Bradley Cooper perhaps has the easier part: as his character Jackson Maine slides into alcoholism and addiction, he is able to chew the scenery a bit. Delicacy not necessary. In fact I think he is better in the more sober scenes, especially near the start of the movie when he first recognises Ally’s talent: for a while it brings back in him the sheer, and shared, joy of making music, and he expresses it almost wordlessly.

So, what can I add that Kermode has not already said? Well, just to repeat, both the leads are really good. Bradley Cooper perhaps has the easier part: as his character Jackson Maine slides into alcoholism and addiction, he is able to chew the scenery a bit. Delicacy not necessary. In fact I think he is better in the more sober scenes, especially near the start of the movie when he first recognises Ally’s talent: for a while it brings back in him the sheer, and shared, joy of making music, and he expresses it almost wordlessly.

But if Cooper is good, Lady Gaga as the ingénue Ally is a revelation. Her emotional trajectory is much more extended, from the hard-nosed young cynic at the start of the film, through her bewildered elation when she first appears on stage with him, to her growing confidence (OK, Lady Gaga shouldn’t have too much difficulty with that bit), to the final concert performance after the moment of crisis. Cooper as director perhaps deserves some credit for coaxing the performance out of her, but all the same her range is quite remarkable for someone with so little acting experience. Not quite none; but nothing to prepare her for this.

But if Cooper is good, Lady Gaga as the ingénue Ally is a revelation. Her emotional trajectory is much more extended, from the hard-nosed young cynic at the start of the film, through her bewildered elation when she first appears on stage with him, to her growing confidence (OK, Lady Gaga shouldn’t have too much difficulty with that bit), to the final concert performance after the moment of crisis. Cooper as director perhaps deserves some credit for coaxing the performance out of her, but all the same her range is quite remarkable for someone with so little acting experience. Not quite none; but nothing to prepare her for this.

Have a look at this clip from the movie: https://bit.ly/2OiNCfG. This is from the crucial scene where Jackson Maine invites a hesitant Ally upon stage for the first time and they sing together: the place where, as Kermode says in his review, their paths intersect. In this video the scene is heavily intercut with moments from elsewhere in the movie, but if you pay attention you will be able to spot the concert scenes among all the rest.  Now watch Lady Gaga’s facial expressions before, during and after the song, especially the final second (literally) of the clip, where a little twitch of her lip perfectly expresses the mixture of bewilderment and elation which Ally is feeling at that precise moment. It’s over in a flash, but that moment tells you she is a proper actor, not just a singer given an acting role.

Now watch Lady Gaga’s facial expressions before, during and after the song, especially the final second (literally) of the clip, where a little twitch of her lip perfectly expresses the mixture of bewilderment and elation which Ally is feeling at that precise moment. It’s over in a flash, but that moment tells you she is a proper actor, not just a singer given an acting role.

This was also one of the two places in the movie where I could for a moment feel the tears welling up. Not to be banal, but it was exactly the same feeling as when one of my compositions was first performed in public; the moment when you feel, well, maybe I do have something to say, and people will listen. It doesn’t happen very often; credit to Cooper and Gaga for catching it so precisely.

The second place was, more predictably, at the end, where Ally sings her farewell song: https://bit.ly/2O1GujL. But although this is very well done, it is just a little manipulative, whereas the first clip feels true. There’s a difference.

The two clips should give you a good feeling for the range of music in the film. I found this in Wikipedia:

[The music includes] elements of blues rock, country and bubblegum pop. Billboard [a music magazine and website] says its lyrics are about wanting change, its struggle, love, romance, and bonding, describing the music as “timeless, emotional, gritty and earnest. They sound like songs written by artists who, quite frankly, are supremely messed up but hit to the core of the listener.”

Jackson Maine is portrayed as a stadium-filling, guitar-heavy country rocker, a bit in the manner of Neil Young (or so I imagine; John, a Young aficionado, may mock me for this). Ally is something else, more like a confessional songwriter. As the film proceeds we see her being transformed by her Svengali-like manager (a creepy turn by British-born Rafi Gavron) into a pop songstress, rather like Lady Gaga herself; and that final song is something different again, a classic belter such as you might find in any hit musical you care to name. Apparently the songs were written by Cooper and Gaga, and the music by Gaga and Lukas Nelson, who performs in Maine’s band. A Star is Born isn’t a musical, but it would be half the film, or less, if the music were poor, or poorly judged. In fact each song, whether or not directly related to events on screen, fits perfectly into its context. I think that is why I liked the movie so much.

Jackson Maine is portrayed as a stadium-filling, guitar-heavy country rocker, a bit in the manner of Neil Young (or so I imagine; John, a Young aficionado, may mock me for this). Ally is something else, more like a confessional songwriter. As the film proceeds we see her being transformed by her Svengali-like manager (a creepy turn by British-born Rafi Gavron) into a pop songstress, rather like Lady Gaga herself; and that final song is something different again, a classic belter such as you might find in any hit musical you care to name. Apparently the songs were written by Cooper and Gaga, and the music by Gaga and Lukas Nelson, who performs in Maine’s band. A Star is Born isn’t a musical, but it would be half the film, or less, if the music were poor, or poorly judged. In fact each song, whether or not directly related to events on screen, fits perfectly into its context. I think that is why I liked the movie so much.

So why didn’t Georgina like it better? She confessed to me afterwards that she was uncomfortable with the free use of the F word. I was quite surprised, as I hadn’t previously detected this degree of squeamishness in her; but then, I scarcely swear at all, and mostly we have not been together anywhere that bad language is at all common, so perhaps the subject just hasn’t come up. In the film I am sure she was referring mainly to a single scene in which there is a furious quarrel between Jackson Maine and his elder brother, Bobby (played with great conviction by Sam Elliott). Every line of dialogue is peppered with Fs: we are clearly meant to notice. Whether it was strictly necessary, I don’t know: it is the anger of the scene, not the language, that is truly shocking. Perhaps the scriptwriters felt the Fs were necessary in order to be true to life.

So why didn’t Georgina like it better? She confessed to me afterwards that she was uncomfortable with the free use of the F word. I was quite surprised, as I hadn’t previously detected this degree of squeamishness in her; but then, I scarcely swear at all, and mostly we have not been together anywhere that bad language is at all common, so perhaps the subject just hasn’t come up. In the film I am sure she was referring mainly to a single scene in which there is a furious quarrel between Jackson Maine and his elder brother, Bobby (played with great conviction by Sam Elliott). Every line of dialogue is peppered with Fs: we are clearly meant to notice. Whether it was strictly necessary, I don’t know: it is the anger of the scene, not the language, that is truly shocking. Perhaps the scriptwriters felt the Fs were necessary in order to be true to life.

But that was just one scene. More to the point, Georgina evidently knows the 1976 version with Barbra Streisand, which I do not, and all along I think she was making silent comparisons. That’s the trouble with remakes: people remember. Kermode suggests that there may be a version of A Star is Born for every generation, so perhaps Streisand’s Star is Georgina’s. But if so, then my Star is Gaga’s.