Ministry of Flat Walks 15 : Elterwater

29 January 2019

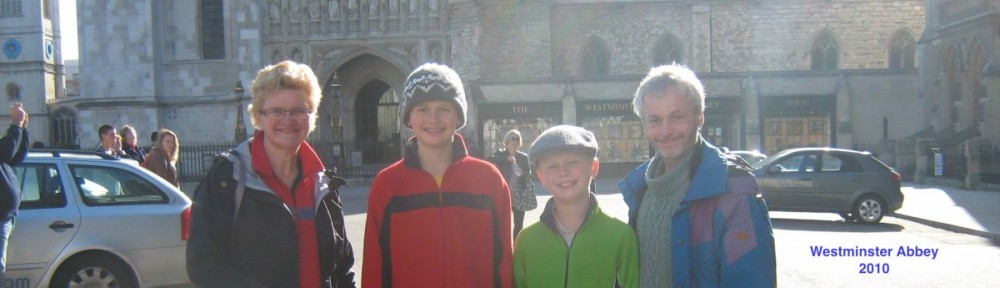

To follow this walk, open another tab in your browser and input this web address: https://bit.ly/2B7Ksng. John and I made this walk together yesterday, a bright, sunny, cold winter’s day: a little cold for walking (I wore my thick red pullover and large padded jacket) but ideal for photography, with all the features of the landscape crystal clear. John had forgotten to bring his best camera but still took some fine pictures with his pocket camera, including all the pictures in this blog except where stated. Thanks, John.

Elterwater is one of the places in Lakeland of which I have the longest memories, going back to weekend breaks with Mum and Dad in the early 1960s, perhaps even earlier. It is a classic Lake District village. (These two pictures are from online sources.) The buildings all have walls of grey slate or whitewashed plaster. There appears to have been very little new build in the last fifty years except that the National Trust has erected a discreet public convenience and opened a decent-sized car park. There is also off-road parking available to the north and east of the village, which does spoil the views a bit in that direction. The village can become very crowded in the summer, so go early or park elsewhere and walk. Yesterday was fine.

The road down to Elterwater which branches off the A593 Coniston to Ambleside road (you can see this in the bottom right hand corner of the map) has other memories for me too. In the summer of 1969 I was employed for a month by the National Trust assisting their rangers who were at the time based at Monk Coniston, just a mile out of Coniston village. One of our duties was clearing undergrowth from areas that had recently been replanted with saplings, without (if we were careful) chopping down the saplings too. It was backbreaking work and eventually they decided it was too much for me, so I was set to work in the nurseries at Monk Coniston instead. However, one of the areas we had to clear was on the slopes to the west of Elterwater and we drove in our Land Rover down this road every day before starting work.

Yesterday, as we were driving into Elterwater, we were bemused to find the way ahead completely blocked by a full-sized articulated lorry which had evidently disregarded the warning signs and attempted to pass through the narrow gap between the Eltermere Hotel and one of the cottages. Goodness knows what the driver was thinking; but anyway he was completely stuck. Fortunately we were able to bypass the obstruction by going round the hotel on the other side, along the hotel driveway.

The walk starts in the National Trust car park and is about four miles long. The first section, from Elterwater to Skelwith Bridge, is almost completely flat: perfect for a there-and-back walk with some classic Lake District scenery, if you really can’t manage any hills at all. After that, there is a short section that is quite steep, but still a walk, not a climb; and the rest of the route is a little up and down, but easily manageable with patience. I strongly recommend making this walk in a clockwise direction, for reasons that will become clear.

From the car park, the walk follows a well-maintained path alongside the Great Langdale Beck which flows through the village. After about a quarter of a mile the path bears left, just before the beck flows into the lake. This is Elterwater, like the village, not Eltermere as suggested by the name of the hotel. The path continues, dead level, with the lake still visible through some straggly trees, and eventually bends right again, close to but at a lower elevation than the B5343 main road. It emerges from the trees near the foot of the lake where it flows into the River Brathay. There is a bench here where John and I sat to eat our picnic lunch, with a terrific view back over Elterwater towards Langdale and the Pikes. We were visited by a pair of swans which seemed to want to share our picnic, but when we had none to spare they didn’t hassle us.

From here the path continues, rising very slightly and passing between road and river where the valley narrows and the river runs faster. The map shows the waterfalls here as Skelwith Force, and you can continue to follow one branch of the path down into Skelwith Bridge, where there are a pub and a good cafê. However, at the top of the falls is a sturdy modern bridge and to follow in our footsteps you should take the other branch of the path across this bridge. The falls are indeed spectacular and John took several pictures, but was hampered by the winter sun low in the sky. The picture I have used is from an online source.

The next section is the stiffest part of the walk, as it rises consistently and quite steeply for about 300 yards, up through the woods before taking a right turn and emerging into meadowland. At least the path is well gravelled and firm under foot. I didn’t enjoy this bit very much, so take your time.

Once you reach the meadowland the path gradually levels out and you can enjoy some stunning views to the north and west. Soon you will come to the first of three lanes, this one leading on your right to Park House, a highly desirable residence with a stunning view. Cross the lane and go through the kissing gate in the fence on the far side.

The path now more or less follows the contour around the side of the hill before climbing very slightly up to Park Farm. In the farmyard you may be greeted, as we were, by two or three free-range hens. They don’t appear to be fenced in at all, so I suppose they must be happy with their lives. Hereabouts I think the path and signage have been improved, as I seem to remember that last time we tried this walk we were not sure which way to go next. Don’t follow the farm lane beyond the buildings but instead go through the small gate just to the right. There is a route marker with a yellow arrow, but it would be easy to miss, so keep an eye out.

Soon enough the path comes to the third lane, which leads to Low Park, another desirable residence, just on the right. Here the owners have clearly decided that they don’t want miscellaneous hikers in their front yard and so have fenced off a narrow path around its left hand edge. Follow this path. The gravel has by now given way to well-worn bare earth, muddy in places, so take care, especially as you approach and then follow the escarpment with the river on your right. Here you will come to a set of steps, edged with pieces of wood, that have been cut into the escarpment. They are steep and lack a handrail, so take great care as you descend. These steps are the reason why following this walk anticlockwise is not recommended.

From the foot of the steps to the road is no more than a hundred yards or so. Turn right when you reach the road and follow it across Colwith Bridge. Here is a junction where the road to Little Langdale branches off up a hill to the left. This road also leads over the Wrynose and Hard Knott Passes and is a magnet for people who fancy themselves, usually with very little reason, as rally drivers, so watch out for traffic.

Take the right turn and follow the road back to Elterwater. About a third of the way along you can turn off to the left and follow a beaten path through the woods, parallel to the road, if you prefer to keep off the tarmac as much as possible. This path ends close to the Eltemere Hotel and you can follow the road from here back to the car park. We were relieved to find that the articulated lorry had gone and the buildings were all still intact. But the driver will not make that mistake again in a hurry.

——————–

Crème brulée

29 January 2019

John and I have just returned from lunch to celebrate his birthday – kindness forbids me to tell you which birthday this is. We had been planning to go to the Rogan & Co bistro in Cartmel, owned by restaurateur and chef Simon Rogan, whose other Cartmel restaurant L’Enclume is the proud possessor of two Michelin stars and has been proclaimed Britain’s best restaurant for four years running by the Good Food Guide. Rogan & Co is almost as good as L’Enclume and a lot cheaper. But it was closed (not surprising, midweek in January, with snow on the hills) so we settled for the Cavendish Arms instead.

Since we bought the house in Cark we have found a number of eating-out places to which we regularly return, and the Cavendish is one of them. I don’t think it’s quite as good as it used to be, but then, what is? The quality at pub restaurants is very dependent on having a chef who knows his business and a manager who cares, and back in 2011 the Cavendish clearly had both. The menu offered a wide choice of unpretentious but interesting dishes and made a feature of how much use was made of local produce.

Today the emphasis on local produce has gone, and the menu (admittedly for a quiet midweek lunch) is much more limited, but we were still able to enjoy home-made steak and ale pie with chips served in individual baskets. Good; not special, but more than adequate, just the thing for a cold day, and filling. For dessert John then had a crumble with apple and winter berries; I had crème brulée.

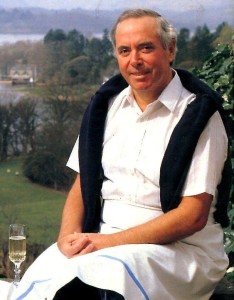

Now, I have a thing about crème brulée. I can still remember the first time we met, way back when Mum and Dad still had Woodgate (their Lake District cottage). They took me for dinner one evening at the Bay Horse pub restaurant in Ulverston. The Bay Horse had recently been taken over by Robert Lyons, a long-time associate and disciple of restaurateur John Tovey who ran the then famous Miller Howe hotel near Windermere. Lyons brought with him Tovey’s investment and goodwill, one of his staff and some of his recipes, and transformed the Bay Horse into an eating place renowned for miles around. He retired a couple of years ago but the Bay Horse is still well worth a visit.

Tovey himself is an interesting figure. He died only last September and his obituary in the Guardian tells us quite a lot about him (https://bit.ly/2Uo5C7L). However, his main significance is that he was one of the pioneers in the great culinary revolution which took place in Britain at the end of the twentieth century. Only in the 1970s the British were still being laughed at, with some reason, for the awfulness of our food. These days we are admired for its diversity, imagination and excellence, and Tovey deserves a share of the credit for that transformation.

But to return to the Bay Horse. For my dessert on that first memorable occasion I ordered crème brulée and received this amazing concoction, served in a glass, consisting of a pale yellow custard with a thin glaze on top. I was instructed to strike the glaze with the back of my spoon, which I did. It broke into shards, just like a thin piece of glass would do, and some of them almost as sharp. The combination of smooth rich custard and sweet crunchy sugar was irresistible, and crème brulée has ever since been one of my favourites.

But I quickly learned that Tovey’s recipe (which this surely was) for crème brulée is not widely followed. The custard has to set first, and then a liquid caramel is poured, carefully and gently, to float on its surface. The caramel solidifies very quickly before it has a chance to sink or merge into the custard. It’s a tricky operation; most chefs and restaurants can’t be bothered. Instead, they scatter a thin layer of granulated brown sugar on top of the custard, and caramelise it under a hot grill or by using a chef’s blow torch. The result is an uneven topping, caramel certainly, possibly burnt in places and gritty rather than crunchy. You can’t break it with the back of your spoon.

I admit that Tovey’s method isn’t easy; I knew this because I once tried it myself. I made the custard, poured it into ramekins, let then chill, then prepared the caramel by melting sugar over a very gentle flame (it’s no good if it burns, not to mention the added difficulty of cleaning the pan) and poured it over the custards. Unfortunately I had made too much caramel and didn’t know when to stop. After the caramel had set in the ramekins I couldn’t break it with a spoon, a knife or (I suspected) a household drill. It had to be dissolved away, and that was the end of my beautiful custards.

Nonetheless crème brulée, from being an exotic treat 25 years ago, is now a regular offering on many restaurants’ dessert menus. Other guests don’t seem to mind that they are being served the cheap non-Tovey version, probably because they have never had a chance to enjoy the real thing. And don’t get me wrong: I like the simple version too, but I can never eat it without a pang of reminiscence for that first encounter.

What annoys me much more than the cheap brown sugar method is that chefs never seem to know when to leave well alone. The classic crème brulée flavour of vanilla custard and caramelised sugar is quite sufficient and needs no enhancement. But at various times I have also eaten crème brulée flavoured with raspberries or chocolate or even lavender (the lavender was scented and horrible, the only time I’ve left some on my plate). Talk about overkill. I was served the chocolate version at the Bay Horse only last year, which made me particularly sad.

At the Cavendish today the menu offered caramel crème brulée, as if there was no caramel in it already. When it arrived, it had been made by the quick method, and scattered on top were tiny fragments of honeycomb toffee, a pointless decoration which stuck in my teeth. Literally. The custard, instead of pale yellow, was a sort of khaki colour and had obviously been infused with caramel in some way – I hate to say this, but probably out of a bottle. The taste was pretty much indistinguishable from natural crème brulée, which at least was an improvement on the chocolate and lavender versions, but why bother?

You can’t improve on perfection.

——————–

Hadestown

25 January 2019

Yesterday Georgina and I went to see Hadestown, a new(ish) musical, at the National Theatre. I booked for this show some months ago, before it had even opened, largely on the strength of reviews and reports from its off-Broadway run in 2016. Music, lyrics, and book were written by Anaïs Mitchell, an American singer-songwriter whose other work is contemporary folk, somewhat in the manner of Joni Mitchell or Suzanne Vega but without their genius. (Check her out on Youtube or Spotify if you think this is too harsh.) Hadestown, however, is billed as a jazz musical, and New Orleans jazz is its primary idiom with only a few traces of folk in the mix. The show was developed by Anaïs Mitchell in collaboration with its director Rachel Chavkin, and I suspect that it is Chavkin who is most responsible for its style and impact.

When the show eventually opened there were some interestingly varied views to be found, above and below the line, in the Guardian review (https://bit.ly/2FjjaPu). But that was long enough ago that I had forgotten most of it by the time we took our seats. At any rate the theatre was completely full, the first time I had seen this since Follies, which was surely a good sign.

We loved it, from start to finish. The show closes in a couple of days’ time and is sold out, so you won’t be able to see it for yourself. But if there is live broadcast or a cast album, or (better) a DVD of this production, don’t hesitate. The production is to transfer to Broadway and deserves to be a monster hit.

The story is familiar enough – Orpheus seeking to rescue his love Eurydice from the Underworld; the only tension (surprisingly strong in the final fifteen minutes of the show) is whether he will succeed. A twist is provided by using the story of Hades and Persephone, who is condemned to spend half of every year with him in the Underworld, as a counterpoint. The setting is more or less contemporary: but it is left deliberately ambiguous whether Hades is a harsh boss man profiting from his indentured workers’ labours, and Hadestown his factory town, or whether he is truly the god of the Underworld and Hadestown is Hell.

The show is almost completely through-composed and the story told through song and movement. The scene is set by Hermes, who acts as a kind of storyteller/master of ceremonies and speaks directly to the audience. Otherwise there are only a few snatches of dialogue here and there.

There are two stand-out performers: Patrick Page as Hades and André De Shields as Hermes. Even silent, Page has a presence on stage that is hard to ignore. He also possesses an extraordinary deep, gravelly voice, speaking or singing, so much so that I wondered whether he was getting a bit of help from the National’s amplification systems. Much of his performance is a kind of chant, rumbling and unpitched but faithful to the music’s rhythms and with the occasional phrase sung in deep, perfect tune. De Shields brings to his role a kind of knowing suavity that seems well suited to a master of ceremonies in a New Orleans dive, complete with mincing dance steps. When he speaks the opening lines you are instantly transported to a world in which you can’t be quite sure what is or isn’t real.

The leading ladies are also pretty good: Amber Gray as Persephone and Eva Noblezada as Eurydice. Their characters are a bit sketchy: Persephone as a sentimental lush who has become bored by Hades and his Underworld, Eurydice as a naïve waif who makes a bad choice and is punished for it. But if this sketchiness is a fault, it lies in the writing, or perhaps in the direction, rather than in their performances. They each sing their solo numbers with character and – I won’t say accurately; there is a looseness to the musical style – but faithfully.

Like some other critics, I was less convinced by Reeve Carney as Orpheus. (It’s only fair to add that Georgina thought he was fine.) He is given the most folky music to sing, less assertive than the New Orleans jazz of the rest of the piece, so perhaps it is deliberate that he seems a bit underpowered. But he sings a lot of his higher notes falsetto, and at times I thought he was unstylistically flat. I first came across Carney in the television series Penny Dreadful, in which he played Dorian Gray: he has a slightly fey quality which suited that role, and which ought to work as Orpheus, but turns out to be just a bit wimpish, although his rescue attempt is properly heroic.

Also in the cast are three Fates, who perform the traditional function of a Chorus, sometimes commenting on the action, sometimes giving it a nudge in the right direction. Georgina spotted that their costumes include a pair of scissors each, which is a nice touch. Their resemblance to groups like the Beverley Sisters or the Three Degrees is probably not a coincidence. And there is another chorus of seven Workers, residents of the Underworld, who contribute some vigorous and characterful dance and movement.

It is not, however, any of the individual performances for which I shall remember this show, but for the quality of the music and movement, and of the overall production. The seven (on-stage) musicians are kept constantly busy, but they never flag and conjure up a remarkable range of sound. The music, not quite blues but with some of the heart of the blues, truly tells the story almost on its own. Only Orpheus’ magical song, with which he gains entrance to the Underworld and even charms Hades himself, is just a bit on the feeble side. Granted that the story sets up an impossible expectation (what modern composer can write a song to defeat Hell itself?), this still seems a tremulous effort. In Wagner’s opera The Mastersingers, his hero Walther is given the task of writing and performing a prize-winning song, and Wagner makes quite sure that it is truly exceptional. Alas, Anaïs Mitchell has not quite managed to follow his lead.

The stage is set in the shape of a semicircular amphitheatre, with the musicians placed around the edge. There is not much use of props apart from some tables and chairs, which are removed half way through the first act, but the lighting (and the accompanying shadows) is effective and atmospheric.

Great use is also made of the theatre’s twin revolves. The central drum, perhaps three metres in diameter, sinks into the floor to suggest descent to the Underworld, but also rises above the stage at times, mostly to symbolise Hades’ power over his domain. Around the centre, a ring revolves and at one crucial moment reverses in direction, symbolising both distance and futility.

Perhaps the production’s greatest quality is its movement. Some is properly dance: not the beautiful pattern-making of ballet, but dance as character and story. Some could not properly be described as dance at all, as when Orpheus (without looking back), leads Eurydice out of the Underworld while the Fates mock and tempt him. Some is half-way between: pretty much every move made by Hermes or Hades or Persephone reflects their character. I don’t know how much of this is to the credit of choreographer David Neumann, how much to director Chavkin and how much improvised by the cast, but it is seamless and expressive. My friend Anne, a great dance lover, who sadly died almost twelve years ago, would have loved this show.

When Hadestown transfers to Broadway I expect it to become notorious for the final number in the first act, Why We Build The Wall. This was originally written way back in 2006, and the wall in question was purely symbolic, a futile gesture of wasted labour and pointless fear; but Donald Trump has made it painfully relevant. Anaïs Mitchell must be astonished by her own foresight. Here is a performance from the 2016 production: https://bit.ly/2ROftqL. This is not as good as the one at the National, which has more powerful orchestration and an ominous pounding beat, but you get the general idea. And you have a chance to admire Patrick Page’s basso profundo Hades.

——————–

Bones

6 January 2019

Having finished the TV series Castle (see my blog of 3 March last year), I looked around for another in similar vein, to entertain me when I was feeling too low or too idle to attempt anything else. I had heard about another series, Bones, with a similar premise but based on the best-selling forensic detective stories by Kathy Reichs which Dad used to read. Georgina bought me a box set of the first season (22 episodes), which I quite enjoyed, but not enough to invest in later sets.

Then a couple of months ago Amazon Prime acquired the rights to the show (all 12 seasons – 246 episodes, no less) and I have been gradually working my way through them, up to half way through the eighth season. At that point I finally gave up, for reasons which will become clear.

The stars are Emily Deschanel as Temperance Brennan (“Bones”) and David Boreanaz as Seeley Booth. She is a forensic anthropologist based at the Jeffersonian Institute in Washington. (The Jeffersonian is a fictional representation of the real-life Smithsonian Institute, but I have no idea whether the Smithsonian hosts real-life forensic anthropologists.) Booth is an FBI agent who calls for her assistance to solve murders where her anthropological skills may be useful. From the start Bones insists on participating in fieldwork so that soon she becomes Booth’s regular partner during cases – not remotely true to life, but hey, this is television. Their contrasting approaches to investigation are shown to be complementary, and as we watch they gradually come to appreciate each other’s abilities. They are assisted by a team of laboratory technicians and supported by a varied cast of recurring characters.

Bones is depicted as possessing genius-level scientific skills and knowledge, but lacking in social skills or awareness of much modern culture. She could descend into caricature, and some of the comedy arising from her character is pretty obvious, but Deschanel succeeds in making her an interesting, believable and (mostly) sympathetic figure. The longest story arc in the show is how she is gradually humanised by her forensic work and her relationships with the team, especially Booth.

By deliberate contrast, Booth draws heavily on his gut feelings which are clearly rooted in experience as an investigator. He seems to spend a lot of time browbeating suspects and other witnesses in the hope of provoking a reaction, but also occasionally reveals a sensitive side. Boreanaz fits the image of an uptight FBI agent to a T. He is gorgeously handsome, and the years seem to have treated him kindly: he looks much the same now as he did when he first appeared in Buffy the Vampire Slayer, back in 1997. Unfortunately his acting is just as stiff now as it was then.

In the first season there were three lab technicians (the squints, as Booth disparagingly calls them). A fourth, titular head of the lab, arrived in season 2. This team are well played by a group of talented young(ish) actors, carefully diverse in race and gender, who ensure that their characters are well defined and differentiated. Their lines include most of the show’s technical gobbledegook, designedly impenetrable, which they carry off with aplomb.

After one of the regulars left the show at the end of season three he was replaced not by an individual but by a rotating crew of four or five assistants. Usually only one of these appears in any given episode, though there are exceptions. This is a nice device employed by the producers to widen the range of characters without drawing too much focus from the principals.

Nearly all the episodes involve stand-alone investigations, but character development arcs bind it all together. Dark humour is shown as one of the ways in which the investigators distance themselves from their frequently gruesome, sometimes disturbing work. There is also a certain amount of slapstick which I find rather unfunny, and the regular display of bodies in various states of decomposition which some viewers might find disturbing (but I don’t). The show’s best comedy comes from the interaction of its range of disparate characters with strongly held opinions and beliefs.

Alongside the investigations, the show naturally focuses on the will-they-won’t-they relationship between its two principal characters. As seems to be compulsory in television drama, everyone else is aware of where Booth and Bones are heading long before they realise it for themselves. I don’t, myself, find the relationship wholly convincing. The producers have obviously heard that opposites attract, and set out to make their leading couple opposites in as many ways as they can find. That makes for sparky dialogue, sure, but not for a believable romance. In particular, Booth seems to me to be rather a bully; I don’t understand what Bones is supposed to see in him.

The problem for any television show which runs as long as Bones has done is that the writers simply run out of ideas. It is the job of the showrunners, among other things, to maintain not just consistency in characterisation and story development but also in quality and tone. This is a weakness in Bones going right back to season 1, during which, among other saner material, we also get cases involving a human hand found in a bear’s stomach, a pirate treasure and voodoo magic. The show is not intended to be taken entirely seriously, but it invariably works best when its stories maintain a certain level of plausibility. The humour then arises naturally and doesn’t feel forced.

I gave up early on a double episode from the start of season 4 which is set in a lazy American scriptwriter’s version of the UK. There are real cultural differences and similarities between our two countries, from which it ought to be possible to construct a decent story. It’s insulting to the whole audience (not just the British) not to bother with the research. And I could not sit through an episode in which Bones and Booth dress up as a knife-throwing duo in order to investigate a murder involving a circus. Best to put this absurdity out of our minds and pretend it never happened.

To offset this, there are also a number of truly outstanding episodes scattered throughout the run, most notably one from season 6 in which Bones, under pressure of work, so strongly associates with a murder victim who like herself seems to live only for work that she starts having hallucinations. This episode is sensitively written and perhaps benefits also from focusing strongly on Bones herself, very well played by Deschanel.

But there are too many episodes that simply rehash the tired clichés of television and genre fiction. In particular, during the first four seasons the team deal with no fewer than four separate serial killers, a trope which has long since been done to death (no pun intended). They are not badly done and achieve some agreeable tension, but it is simply lazy of the writers, and tedious for the viewers, to recycle this plot device over and over again.

It was the re-appearance of a fifth serial killer half way through season 8 that finally caused me to give up on the show. He was given not only superhuman skill at computer hacking (another sad trope) but also a totally implausible ability to second-guess the investigators, break into their homes and manipulate their lives. At this point Bones’s connection with reality, already tenuous at times, was decisively broken, and it was no longer possible to take the show seriously.

A few weeks ago I read one of Kathy Reichs’ Bones novels which I bought at the second-hand bookshop in Sedbergh. Honestly, I don’t see what all the fuss is about. The plot is padded and routine, the shock value minimal, the characterisation weak, the writing flabby and uninspired. Whatever the TV series’ flaws, it is a lot better than the source material.

——————–

What we did at Christmas

4 January 2019

For the last couple of years John and I have chosen to spend Christmas up at Cark. John comes down to Oxted for a few days beforehand so he can visit the latest exhibitions and we can go together to the theatre, and then we drive north together. We take a circuitous route so as to avoid the never-ending road works and consequent congestion on the M6 north of Wolverhampton.

This Christmas we set off from Oxted on the morning of 21st December and arrived in Manchester in the late afternoon, where we stayed overnight at John’s home. The following day we completed the journey to Cark. The weather was chill and drizzly, and the house, unsurprisingly, was cold. We turned on the heating and put on extra sweaters, and started our preparations for the holiday. John decorated the Christmas tree; I set out the Christmas cards. We also put up our jigsaw table, a drop-leaf table which is folded up and kept out of the way for the rest of the year, in anticipation of long winter evenings and wet winter days.

In fact we were moderately lucky with the rain. It drizzled from time to time, but only once did we have a real daytime downpour. However, the skies were persistently grey and threatening, and we did not venture on any long walks. We only had one sunny day, Christmas Eve, and unfortunately that was the day John chose to put a safety pin into his ear.

John had been suffering from a sniffly coughs and cold, which caused a loss of hearing in one ear. He decided he needed to scoop some wax out of his ear and that the blunt end of a safety pin was the best available instrument to do so. Unfortunately he lost his grip on the pin. He came to me complaining that he thought the pin had got stuck in his ear, and would I have a look?

I couldn’t see the pin at all, so we had little choice but to head off to the urgent care unit at Westmorland Hospital in Kendal. There were seven or eight other patients waiting for attention and I feared a long delay, but in fact the unit was quite prompt; we had to wait for less than an hour. When John was called for examination I had to wait outside, but he tells me that two separate nurses looked in his ear and failed to find anything. They told him they would arrange an urgent outpatient appointment; we should go home and wait to be called.

So we went home; and John found the safety pin on the bathroom floor. Neither of us had thought to look for it. He cancelled the appointment.

The wettest day was the 28th, when we drove north to visit my cousin Tanya and family at their home in north Cumbria, on the edge of the Tindale Fells, east of Carlisle. They have been living there for more than a year but this was our first visit. John and I loved the house, which is three old mining foremen’s cottages knocked together into a single home, warm and welcoming. But the location is awfully bleak and remote.

Around the house they have quite a bit of land where they are keeping (at the last count) two cats, five hens, three alpacas and two tortoises. Tanya calls them her menagerie, though she may also have been including her family in that description. The tortoises stay indoors during the winter but even so they were very drowsy, rather a shame as when they are up and about they can be very characterful and amusing. Evidently, even indoors, they feel the cold and don’t like it.

We managed some short walks at favourite places: out on the sands at Bardsea where the tide was very low, at Tarn Hows, Coniston, Cartmel and Hawkshead. Some of these may eventually get blogs of their very own (Tarn Hows already has: see 31 October 2017). We also had some nice meals: Tanya cooked roast beef with all the trimmings, we visited the Bay Horse pub/restaurant at Canal Foot, Ulverston for our favourite ciabattas and chips, and I cooked spiced beef and roast ham.

In between times we managed to complete not one but two 1000-piece jigsaws, both of which Georgina had lent to us: the Bizarre Bookshop 2 (these days even jigsaws come with sequels, it appears) and I Love Winter by Mike Jupp. We must have worked hard at these, or perhaps they were not so very difficult, as to complete two jigsaws in nine days is good going for us. Unfortunately, somewhere along the way we managed to lose a piece from I Love Winter. Georgina suggested, rather unfairly, that we should look for it in John’s ear.

The first time I can remember doing jigsaws was at the age of thirteen, in a side ward at Mossley Hill Hospital in Liverpool, where I was confined to bed after having my appendix removed. I don’t recall what the jigsaws were, but my memory of doing them is absolutely clear. I remember the appendicitis too, and the aftermath: for about a week it was too painful for me to stand up straight, and I was not allowed to play cricket at all that summer, much to my disappointment, because of the risk that I might tear open the scar.

It’s funny how some memories, like this one, are so clear when others vanish without trace. The next time I remember doing a jigsaw was during a family holiday in Plymouth in 1975. It was our last family holiday together before I started work in September, and the only holiday I have ever had in the West Country. I have several memories from that holiday: travelling on a diesel train from Plymouth up to Gunnislake; Dad going to a fish-and-chip shop (something I think he liked more than Mum did) for our supper; crossing the River Tamar on a car ferry; map-reading us along the byways of Devon to avoid the horrendous traffic on the A38. But the jigsaw on the dining table is as vivid as any of these.Jigsaws have become a tradition for John and me at Christmas. I think it may have been our first Christmas at Cark when we did a jigsaw of Rousseau’s famous painting, Surprised! I have always liked this painting for its drama, and for the wonderful tiger – just look at those eyes, and that stripy (not in the least true-to-life) tail. But doing the jigsaw gave me an entirely fresh appreciation of the artist’s skill. Rousseau’s style may be naive – in his lifetime he was frequently mocked. But when you put the jigsaw together piece by piece you get to see the remarkable range of greens, greys and browns which he conjures up. The plants, like the tiger, are entirely imaginary, yet equally vital.

Encouraged by this success we have done more art jigsaws, including Renoir’s famous The Ball at the Moulin de Galette and Cézanne’s The Card Players. We also attempted Seurat’s La Grande Jatte, but were defeated, after completing most of the puzzle, by the large dark-shaded area along the bottom edge. No doubt we could eventually have completed it by sheer trial and error, but there would have been no joy in doing so, only dogged persistence, and that wasn’t enough.

Over time Georgina has given us several fun jigsaws, not just the two we did this year but also one with a design based on Barcelona landscapes, one with an abstract Australian pattern which turned out to be surprisingly engrossing, one with a Christmas flavour which we did in Oxted the year I had my radiotherapy, one in black and white showing construction workers in New York high above street level, and another Mike Jupp design. We have yet to attempt the last two of these. Georgina is obviously a jigsaw connoisseur, which John and I would never claim to be.

On my way home from Cark I stopped in Shrewsbury to visit Chris and Janet. They took me out for lunch – very nice, but I ate far too much; and afterwards we had a look at a jigsaw Janet has just started, a detailed contour map of the northern Lake District. Janet is a fellwalker and I think she hoped this would give her an advantage. I like map jigsaws – actually, I just like maps; but this one was really hard, not least because the picture on the box had print so small that it was scarcely readable even with a magnifying glass. There is no point in a jigsaw that is too easy, but this struck me as not playing fair.

Thanks to John, as always, for the pictures from Tanya’s house and of the jigsaws.

——————–

Company

2 January 2019

A couple of weeks ago Georgina and I went up to the West End to see a new production of Stephen Sondheim’s musical Company. It was a Christmas treat for us both: I had been looking forward to the show for months.

It was good, but not quite as good as I, or I think Georgina, had hoped. Perhaps our expectations had been raised unfeasibly high by Follies, which we saw a year ago (see my blog of 16 September 2017). Somehow this show never quite caught fire.

Company was first produced in 1970. Sondheim wrote the music and lyrics. The book (story and script) is by George Furth, who also collaborated with Sondheim on Merrily We Roll Along but was otherwise best known as a film and television actor. The show is not through-composed: there is quite a lot of spoken dialogue.

The central figure is a single man, Bobby, living in Manhattan. We see him first on his 35th birthday and most of the show implicitly takes place in a series of flashbacks. There is next to no story development. Instead, we see Bobby’s interactions with five couples (four married, one about to be married) who are his friends and with his three not-too-serious girlfriends. The married couples all have problems of their own, but all seem worried that Bobby is still single and want to see him find a partner.

For this production Company has been updated, with Sondheim’s blessing. Bobby is now a woman, Bobbie, with three not-too-serious boyfriends. The about-to-be married couple are two gay men. The producers’ intention, apart from giving the show a more contemporary flavour, seems to be to sharpen the implied dilemma for Bobbie. As Hadley Freeman writes in a programme note: “the single-woman story is more interesting … because it comes with a built-in deadline. If a single woman wants to have a child, she needs to make her decision by her late thirties.”

I understand the point; but it is not as effective as the producers intend. In the original, Bobby is under a lot of social pressure to conform and settle down. During the show he has the chance to observe the pros and cons of his friends’ marriages, to see the companionship and bickering, the love and misunderstanding. Indeed it is all very neatly summed up in his final number, Being Alive. But there is barely a word about children, nothing at all about the joys and travails of becoming a parent. The dilemma as described by Hadley Freeman is notable only by its absence. As a result the gender-swap seems slightly pointless.

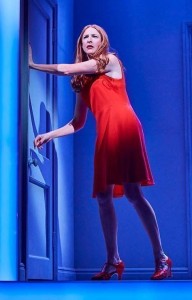

Bobbie is played by Rosalie Craig, whom we had seen five years ago in Tori Amos’s musical The Light Princess at the National Theatre. She was very good in that, better in fact than the show as a whole, which suffered from so-so production (some very good, some a bit corny) and ho-hum music, rather derivative despite Amos’s songwriting credentials. Then I saw Craig again a couple of years ago as an excellent Rosalind in Polly Findlay’s production of As You Like It, also for the National. So I know she can both sing and be funny. You might think she would be perfect for Company: evidently the producers though so too.

But she isn’t, not quite. On reflection I think she is a little underplayed. For much of the show Bobbie is a spectator, observing the lives of her married friends. In her scenes with two of her not-too-serious boyfriends (PJ and Theo) they do most of the work, and when she loses them she seems neither surprised nor disappointed. Only with the third, Andy, who is a flight attendant, do we see a brief spark: they sing a duet, Barcelona, which is half satirical, half poignant – very Sondheim. But by the end of the scene Andy has gone the way of the others. So Bobbie is a bit of a blank slate. She needs work to make her into a character you will empathise with or care about, and Craig doesn’t quite deliver.

Possibly she also suffers from the fact that her music wasn’t written for a female voice. On Youtube there is a short clip of Craig belting out Being Alive: https://bit.ly/2GSqa6J. She is pitch perfect, but I don’t find much character in this. By comparison, here is a performance by the Broadway and TV star Neil Patrick Harris: https://bit.ly/2RrkeFL. Vocally he is a lot less precise, but far more relaxed. His tenor voice brings weight to the final verse without shouting, which Craig’s soprano, almost a yell towards the end, does not.

There are some good moments in the show. In particular the director and cast have dreamed up some terrific visual comedy to accompany the number Not Getting Married Today. This is a horribly difficult patter number, performed faultlessly here – despite all the distractions – by Jonathan Bailey as Jamie (renamed from Amy in the original). Several versions can be found on Youtube and I strongly recommend, even if you never follow up any of my other links, that you have a look at this one, by Katie Finneran: https://bit.ly/2VpChuY. Just while preparing this blog I have watched this clip three or four times through and it makes me smile every time.

Of course we didn’t pick up all the words in this number. I defy anyone to do so on first hearing. The gist was enough. We did find, though, that despite our best-in-house (well, almost) seats, we missed quite a lot of the spoken dialogue throughout the show. I’m not sure whether the problem was with us, or with the theatre acoustics, or with the performances: the show is set in Manhattan, and perhaps all the actors are speaking authentically fast, or just trying too hard to get their New York accents right.

What else is good? Apart from the slight disappointment of Craig, the performances are fine and the five couples are deftly characterised. The singing is well up to scratch and the several ensemble numbers, some of them very difficult, work well. But I must mention Patti LuPone, an authentic Broadway star, who performs her iconic number The Ladies Who Lunch with considerable verve. Of course, she’s done this before. Here’s another link, to a truly matchless concert performance: https://bit.ly/2vjO42R. It’s just a shame we don’t get more from her; this is her only solo number in the piece.

I was a little disappointed with the movement and choreography: there is too much shuffling around from one position to the next. But I may here be subconsciously, and unfairly, making a comparison with Follies, in which dance and movement are an integral part. Company is not really a dance musical at all.

The musicians are conducted by Joel Fram and placed, not in an orchestra pit as usual, but in a kind of loft built (but visible) above the stage. I’ve never seen this before in a West End theatre. The conductor is invisible to the performers on stage, and so cannot direct them: it must all be worked out, every last detail, in rehearsal. This kind of music demands absolute rhythmic precision, and their togetherness was extremely impressive.

While I was preparing this blog I looked at a lot of Youtube videos and there are two more I want to mention. First is a clip showing Sondheim coaching three young Guildhall students in Not Getting Married Today. The young girl singing Amy is remarkably good, but what’s most interesting is the detail which Sondheim points out for the students, showing us how carefully he has crafted the music and words: https://bit.ly/2QhIyFp. There are several other videos showing him coaching students in numbers from his other shows, if you find this one interesting.

And second, a performance from New York in 2011. It’s fairly remarkable to find the entire show on Youtube, so catch it now before the copyright police get it removed. There are Spanish subtitles, but that shouldn’t worry you. To be honest I think this is a better production, despite being only semi-staged, than the one which Georgina and I saw. It makes a virtue out of the limitations on the staging, and you can hear all the dialogue: https://bit.ly/2CKeG0G. The performances by Neil Patrick Harris and Katie Finneran, mentioned above, are from this show.