As You Like It

24 March 2019

Janet and Chris, John and I went yesterday to see the RSC’s latest production of As You Like It, directed by Kimberley Sykes, in the main theatre at Stratford-on-Avon. AYLI is one of Shakespeare’s most popular plays, regularly produced in Stratford and London, always drawing good audiences. This was the third time I had seen the play since 2013. Unfortunately I think this may also have been the least satisfactory of the three.

There are, of course, some good things in it. In the RSC’s current house style several of the roles are gender-swapped, among them the melancholy Jacques, very well played here by Sophie Stanton. There has to be some edge to Jacques, to offset the sweetness elsewhere, but not so much as to unbalance the play. Stanton gets it exactly right and, in particular, delivers the famous speech about the seven ages of man with just the right degree of sardonic detachment.

I also liked the gender-swapping of Duke Frederick’s sidekick Le Beau (though should it not have become La Belle?), played with great relish by Emily Johnstone in a platinum blonde bob wig and tottering high heels.

I wasn’t so sure about Amelia Donkor as Silvia (in the original, Silvius), the shepherd in love with Phoebe, who spurns her in favour of “Ganymede,” that is Rosalind in drag. This piece of gender-swapping undermines the logic of the final scene, where Rosalind’s true identity is revealed and Phoebe, disappointed, most return to Silvius. (Work it out!) Donkor plays the role from start to finish with a charming smile, but without the earnestness of love that Silvius is usually given. Whether this bland charm was Sykes’s decision or Donkor’s, it doesn’t work.

I was also not convinced by Charlotte Arrowsmith as Audrey. Arrowsmith is profoundly deaf and she plays her entire role in sign language interpreted by Tom Dawze as her lover William. This arrangement, actor as signer, seems forced. I do not speak or understand sign language, but Arrowsmith’s signing seems to me grossly exaggerated for effect, like a comic actor who never stops shouting. The whole arrangement seems to me not only tokenism, which is scarcely in doubt, but verging on mockery. Is this somehow made acceptable by the fact that it is Arrowsmith herself who is the perpetrator?

The whole production seems to me to have this hit-and-miss quality. Some of the music, by composer Tim Sutton, is very good. In particular his setting of the famous Blow, blow, thou winter wind is gorgeous, achieving a near-perfect blend of fantasy and folksiness, and avoiding all pastiche – the trap into which most Shakespeare settings fall. But there are also a small number of irruptions of recorded music, mostly for comic effect, which seem misplaced.

The set, as usual at Stratford, is minimal. At the start the stage is occupied by a large green rug which I am sure we all expected to persist, suggesting the green forest: but in fact it was half-rolled up in an early scene as a gesture of anger, thereafter becoming a trip hazard for the performers until it was shunted out of sight at the interval. In fact for the forest scenes, basically all the play after the first act, any suggestion of greenness was conspicuously absent. Very odd, almost perverse.

The play concludes with Hymen, the spirit of marriage, appearing as a deus ex machina, to preside over the final scenes of reconciliation and unity. Here this production achieves a genuine coup de théâtre, as a 15-foot high puppet, basically a framework with some covering and a bland neutral face, is brought on from the wings erected on stage. It feels just like the kind of celebratory image a rustic community might contrive.

Perhaps the aspect of the production I most disliked was the lighting. No effort seems to have been made with it at all. Usually the RSC compensates for the largely bare apron stage with clever lighting effects to evoke mood and setting. Not here. After the action moved to Arden, which transition was itself done with horrible clunkiness, the stage remained fully illuminated more or less for the rest of the performance. It was obviously deliberate, almost Brechtian in effect. Perhaps it was intended to suggest the original open-air staging. The programme notes hint at this, and it would also explain some of the gratuitous audience participation elements. Though John really should have caught the piece of “pancake” that came flying his way. (Sorry, in-joke – you had to be there.) This kind of engagement with the audience is stock in trade at the Globe, but here it feels contrived and a bit lazy.

One good feature which we liked and hadn’t seen before was that the roles of the good and bad Dukes (the exile and the usurper) and their respective entourages are doubled. This certainly helps to point Shakespeare’s intended contrasts of town and country, constraint and freedom, good and ill nature. The Dukes are played by Anthony Byrne, and though neither is a major role he certainly succeeds in characterising them very differently. I thought I detected more than a hint of the great National Theatre stalwart Michael Bryant in his appearance and performance.

You have probably noticed that so far I haven’t said a word about the principals’ performances. I regret to say that this is because they were mostly unconvincing. There is nothing wrong with their diction: they, and indeed the whole cast, speak the lines exceptionally clearly, as we have come to expect at the RSC. But characterisation seems absent.

Lucy Phelps as Rosalind has earned plaudits elsewhere (see for instance this review in the Evening Standard: https://bit.ly/2HEuAxz), but I found her disappointing. There is a lot of physicality in this performance, full of gesture, striding and leaping across the stage. But this is no substitute for personality or passion. In the crucial scenes where Rosalind, as Ganymede, induces Orlando to imagine that she is Rosalind, there is neither frisson nor laughter. This is where Shakespeare’s wit should be most on display; sadly, in this production it is absent.

David Ajao as Orlando turns out similarly bland. In the opening scenes where he confronts his wicked elder brother Oliver (Leo Wan) and defeats Oliver’s wrestler Charles (Graeme Brookes) there is a real air of physical confrontation which promises well for the rest of the show, but when the scene shifts to Arden Ajao seems out of his depth, lacking any lightness of touch. Shakespeare of course intends Rosalind to run rings round Orlando, but as played by Ajao he seems too dull-witted even to be bewildered. If Rosalind loves this Orlando it is for his muscles, not his mind. We will be seeing Ajao later in the summer, in Measure for Measure, where I expect him to give a better account of himself.

It is the supporting roles which shine most brightly here. I’ve already mentioned Sophie Stanton and Anthony Byrne as Jacques and the Dukes. But I also liked Sophie Khan Levy as Celia, which can be a thankless role as Rosalind’s sidekick and stooge: she makes the most of her opportunities, mostly in the first act, and earns her laughs. Perhaps she should have been cast as Rosalind.

And, although he cuts a grotesque caper, it is hard to dislike Sandy Grierson as the jester Touchstone. Here he seems to be playing much more to the audience than to the exiled Duke’s court, and quite a lot of his courtship of Audrey seems to have been cut, or neutered by the complications caused by her deafness. But the physicality which defines, and in truth limits, this production is entirely apt for Touchstone, and he doesn’t disappoint. Last time we saw Grierson was a couple of years ago in Dido Queen of Carthage, and before that in Doctor Faustus, in which he shared the principal roles (Faust/Mephistopheles) with Oliver Ryan. This latest performance suggests he would be equally good as Falstaff or Coriolanus. Hint to future casting directors: keep him in mind.

——————–

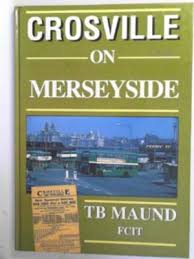

Crosville

16 March 2019

In a recent blog (23 February) I mentioned a visit to the second-hand bookshop in Cartmel. When the shop is open (it often isn’t; they do most of their trade on the internet) we can rarely resist the temptation to go in and browse. And then it only seems polite to buy a book or two, even though many of the prices are quite steep for second-hand, and there is no room on our bookshelves anyway.

Last month the bookshop was clearing out old stock and offered a 50% discount on all the books in its shelves upstairs. So we went to look; and after a while John drew my attention to a book he had found about Crosville buses. With the discount, it was just £8, too good to miss.

If you lived in or visited Merseyside, or Cheshire, or North Wales any time until the mid-1980s, you will recognise the name Crosville. Otherwise you are probably a little bemused. Crosville was the name of a bus company which operated in those areas from the early 1900s to the late 1980s when bus services outside London were deregulated. The name Crosville is a portmanteau of its founders’ names, George Crosland Taylor and Georges de Ville, and has no geographical significance.

Originally Crosville was an independent company, but in 1942 it was taken over by the Tilling Group, which owned a string of bus operators nationwide. Tilling was nationalised under the Attlee government and came under the auspices of the British Transport Commission, but Crosville and the other operators retained their brand names.

Of course, as a boy in Liverpool in the 1950s and 1960s, I knew none of this history. All I knew was that the Crosville buses were a bit special. They ran alongside Liverpool Corporation’s own bus services, but to destinations beyond the city boundary, like Prescot and Widnes, Warrington and Chester. The buses were a distinctive shade of dark green, darker than the Corporation vehicles, and they had a different shape too. The Corporation buses were a mixed bag, the older ones certainly dating back to the war and earlier, but were gradually being replaced by standard Leyland models. Most of the Crosville fleet, however, consisted of Bristol “Lodekka” vehicles, which as the name implies were specially designed with a reduced profile so as to fit under low bridges. It gave them a curious squat appearance, and tall people on board had to duck their heads, which I did not mind at all.

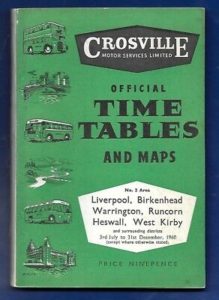

Crosville buses had other features by which, as a small boy, I was intrigued. Most of the buses had platform doors, though they were hand-operated by the conductor and I rarely saw them in use. (Perhaps they were reserved for the rural services, with longer distances between stops.) Crosville published a real timetable, like a railway timetable, showing calling times at intermediate stops and destinations, whereas the Corporation timetable merely listed starting times. And the Crosville conductors had distinctive Setright ticket machines with tickets on a roll that were printed as required, whereas the Corporation conductors used Bell Punch machines which issued five denominations of fixed-price tickets. I can still remember these details from more than 50 years ago; somehow they are engraved in my memory.

My first encounter with Crosville must go right back to the 1950s when we were still living with Mum’s father, my Grandpa B (for Bradbury – there was also Grandpa C for Coulshed), in Score Lane, Liverpool. At the bottom of the road was a bus stop where we could catch a Crosville bus, either into the city centre or out to Prescot. These routes were originally numbered 116, 116a and 168, which was interesting too, as the Corporation route numbers ran from 1 to 99. I wondered where all the other routes (100-115 and 117-167) were. Even as a small boy I had a curiously logical mind.

Then at some point Crosville renumbered all its routes, and the Liverpool services were prefixed with H. So the 116 became H8 and the 168 became H16. I never found out what the H stood for – Huyton? Halton? From the book I bought in Cartmel I now discover that it was entirely arbitrary, which I think I had dimly suspected but wanted it to be otherwise. I remember that the H coding didn’t extend across the River Mersey: in Birkenhead and on the Wirral, the Crosville routes were prefixed with F. Of such improbable details are memories made.

Mum used to take me for rides, not just on her shopping expeditions into town but for the fun of it. We would go by Crosville to Prescot, then on a St Helens trolleybus, and back home by a different route on another Crosville. The trolleybuses were withdrawn in 1958, which enables me to put a fairly specific date on this memory. We used to sit upstairs at the front and look ahead, which is still my preferred seat on buses and trams.

I must have enjoyed these expeditions, which I suppose would be rare enough in a 3-5 year old, but I now think Mum also enjoyed them because they took her out of the house and away from Grandpa. Not that he wasn’t loved, but I think he had a very old-fashioned (even for the 1950s) view of family rights and duties which I am sure drove Mum to distraction. I remember the day in 1963 when I came home from school and Mum told me he had died. Even to a 10-year old the sense of relief and freedom around the house (we had moved by this time, but Grandpa came with us) was palpable.

I have two more specific memories of these outings. Occasionally we would go upstairs on the bus and find that there was no central aisle between two rows of seats but a sunken corridor to one side of a single row of bench seats, each with room for four people. You had to step up into the seats and I wonder, now, if this was an early design feature of the Lodekkas, to provide more headroom. It’s not a very practical arrangement and was abandoned on later models. I have never seen it since, and can find no photos to illustrate it, alas.

My second memory has more recent echoes. I have an image in my mind of waiting with Mum on the top deck of a Crosville bus which was standing by a blank whitewashed wall. When first Dad and then Mum were taken into Whiston Hospital a few years ago I was astonished to find this very location at the end of the road from Huyton just next to the hospital. It was unmistakeable. I have not a clue why this particular image had stuck in my mind, but there it was.

One year for a Christmas present Dad gave me a Dinky toy model of a double decker bus which he had meticulously painted in Crosville livery (dark green with a yellow stripe). He had even managed to write Crosville in tiny letters on the side, though he didn’t quite manage to reproduce the logo, at which I was unreasonably disappointed. John still has this model bus somewhere and if he can take a photo of it I will add it to this blog.

Crosville was not the only independent bus company operating in Liverpool. Services to the north of the city, to Formby and Southport and Ormskirk, were operated by Ribble, which was owned by the Tilling group’s rival conglomerate British Electric Traction, also nationalised under Attlee and deregulated in 1986. Ribble operated the buses which ran outside the front door of my Grandma and Grandpa C in the village of Banks near Southport. One of the services was the X27 which ran from Liverpool to Skipton. Grandma and Grandpa took me once all the way to Skipton and back for an outing, but I don’t remember anything much about it, except that whatever the X designation may have implied it was certainly not an Express service.

The Ribble buses were bright red, even more exotic than Crosville, and had an even more arcane (but no doubt equally arbitrary) route numbering system. Ribble had their own bus station in Liverpool, at Skelhorne Street, next to Lime Street railway station. Ribble’s operating area extended way to the north, throughout rural Lancashire and the Lake District, but like Crosville they are now defunct. So far as I know no-one has yet written a book about them. If they do, I will buy it.

——————–

Bonnard and Berberian

15 March 2019

When John comes down to Oxted, as he does three or four times a year, we like to cram as much into his visit as we can. So last week, apart from the two plays which John and I saw on Saturday and are the subject of my previous blog, we also went, on Friday afternoon, to an exhibition at the Tate Modern of paintings by the French post-Impressonist painter Pierre Bonnard; and, on Friday evening, to see another play, Berberian Sound Studio, at the Donmar theatre. John had been to yet another exhibition on Friday morning, but I gave that a miss. One a day is enough for me.

The Bonnard exhibition was a grand affair with more than 100 paintings spanning the last forty years of the artist’s working life. We enjoyed it and spent a couple of hours in the gallery. I hadn’t previously known much about Bonnard except for the post-Impressionist label and for a vague association with bright colours. I came away with mixed feelings: some of the paintings are top class, some not so much, a few seem (to my untutored eye) a bit impatient and confused. I was right about the colours, though.

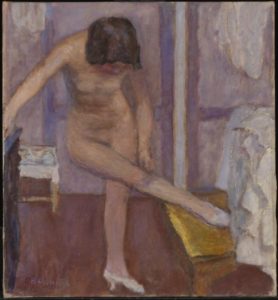

It’s not so much that Bonnard was patchy; all but the very greatest artists produce work that varies in quality. In one sense he is remarkably consistent, since his style does not seem to have changed very much over a long career. Or perhaps I should say his styles, for he seems to have several. Most of the paintings I liked best were the nudes – not erotic or voluptuous, as in Velasquez or Rubens, but in everyday poses around the house. They are beautifully drawn, with a attention to line that isn’t so noticeable in his other paintings. I believe the model was almost invariably his mistress, later his wife, Marthe: slender and petite, but in these pictures almost featureless. We did notice that Bonnard doesn’t seem to like painting faces. Mlost of the human figures in his paintings are seen in profile, or from behind, or with their features obscured as in this example.

Marthe also appears fully clothed in many of the next group of his paintings, the house interiors, sometimes with a dog or cat (you can just see the tip of its black tail in this one). The colours in these paintings are heightened, the perspective is often heavily foreshortened, and you can see the artist has a fondness for pattern. We lost count of all the check tablecloths – very French. These paintings have a warmth to them which suggests that Bonnard was a contented man and goes a long way to explaining their popularity. He painted similar scenes many times over: this doorway appears again and again, in different lights and colours.

And then there are the landscapes. Some of these are very striking, and show the impressionist roots of his style more strongly than any of his other work. These two, the Yellow Boat and the Pont de la Concorde, are among the best paintings in the exhibition.

But perhaps he needed something like the bridge or the boat to provide a focus. Some of his other landscapes, including the giant painting Summer, seem to me to lose focus in great swathes of undifferentiated colour.

I thought I detected here a similarity with another popular modern painter, David Hockney, some of whose landscapes also have sweeping expanses of bright colour. But Hockney is invariably inviting you to look at something. I cannot see any equivalent intention here.

Bonnard was very productive throughout his career, and I wonder if he was too easily distracted. I thought I detected a problem of quality control, which surfaces in the many repetitions and in the colourful but sometimes unfocused landscapes.

I had booked for Berberian Sound Studio on the strength of the Donmar’s reputation plus some decent reviews and the thought that John might be particularly interested by the theme of the play. Its protagonist is the sound engineer on an Italian giallo movie (see wiki: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giallo), a sub-genre in which I knew John was interested, and the publicity material promised that sound effects, as for film, would be produced live on stage by the actors. Sounded promising.

What I didn’t realise was that the play is itself an adaptation by writer Joel Harwood of an actual film of the same title by the British director Peter Strickland which has the same subject but, as we discovered, goes further in its twisting of reality and morality than the stage play attempts. For instance: a recurring idea is that the sound engineer, Gilderoy, is striving in vain to get reimbursement for his airline ticket to Italy. It starts as a joke and becomes gradually more sinister. But in the film (as I understand) he is eventually told that he can’t be reimbursed because his flight never existed. The play doesn’t offer that twist.

This isn’t intended as a criticism. Giallo is intensely cinematic and lurid, thematically linked to the exploitation movies of American cinema but with an added dash of Italian style. According to the programme notes, giallo often also has a hallucinatory quality in which the boundaries between art and reality are blurred, and Strickland’s film adopts a similar style. The stage play eschews most of this and instead offers a psychological horror fable. It plays for an hour and three quarters without an interval, and for once I thought the one-act structure well justified by the content.

The action all takes place indoors, with nothing to show whether it is night or day. We are in an Italian sound studio, as shown by the illuminated sign demanding Silenzio above the stage when the play begins. At the back of the stage are two glass-fronted booths: one, barely larger than a telephone box, with microphones for the performers, one somewhat larger with the sound recording and mixing kit for the engineers.

Gilderoy is young and naïve, and at the start has no idea what he has got himself into. The director who hired him, Santini, is nowhere to be seen; the technical crew treat him rudely and dismissively, and they and the performers speak mostly in Italian, which Gilderoy doesn’t understand. I understand that this is a device to emphasise Gilderoy’s alienation, but after a while it risks alienating the audience too. Overdone, I think.

We quickly realise that Santini has hired Gilderoy precisely because he can be exploited and manipulated. Snippets of dialogue – there are few extended conversations in the entire show – reveal the grotesque horror of the images for which Gilderoy has to find the sounds. He is initially appalled and unbelieving, but also fascinated by the technical challenge; by the end, he too has become a manipulator of the two young women who provide the voice acting for the film.

The Guardian describes Gilderoy as the dork from Dorking, which is pretty much spot on. He is played by Tom Brooke, whose distinctive hollow-cheeked looks and gangly manner suit the character very well. I thought he did the alienation beautifully but was a little less convinced by his absurd innocence. Perhaps the fault for that lies with the script. For all the incidental detail, including tape-recorded messages from Gilderoy’s mother in England, he and the other characters seem to me to be types, not personalities. This is not a character-driven play.

We do get the promised demonstration of Foley art (Foley, named after one of its progenitors Jack Foley, is the art of reproducing sound effects for film). Who knew that twisting a stick of celery into a microphone could so graphically represent the tearing of human bones? Ugh. The publicity material promises melons too, but they were a bit disappointing: less squelch, more thud. Could be anything really.

But all this is a sideshow. The play’s principal themes, in this unlikely and slightly unnerving setting, emerge clearly: the exploitation of innocence by power, and of women by men. The film itself (from which we hear extracts but see nothing) is exploitative and corrupting of its audience; the director exploits and corrupts his crew. Very different from our usual theatrical experiences, weird and unsettling, and very well done.

——————–

Rare plays by master playwrights

14 March 2019

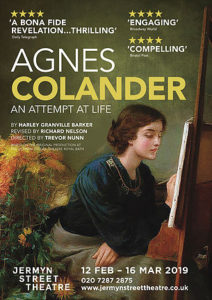

John came down to stay with me last weekend, and on Saturday we went twice to the theatre, to see two rarely-performed plays. The first was The Price by Arthur Miller, which I had never seen; the second, Agnes Colander by Harley Granville Barker, which almost no-one has seen. We’ll come back to that in a minute.

Miller is one of the twentieth century’s finest and best known playwrights. But his fame rests on only a small proportion of his total output. Wikipedia lists 37 plays (although some appear to be reworkings of earlier material) but of these only four are revived at all regularly. Critics seem to think that the quality of his work declined after the mid-1950s when he had completed just 14 of those 37. I can’t confirm this, but certainly John and I went to see his next-to-last play, Resurrection Blues, in 2006 and thought it a poor effort.

The Price was written in the mid-1960s. We enjoyed it, especially the second half which is full of classic Miller themes. But there’s no denying that the play has an odd structure. It starts like a Broadway comedy but ends as an American tragedy.

We find ourselves in a Manhattan loft where Victor Franz is getting ready to sell off the furniture and household chattels once owned by his father, who was broken in the Great Depression. The central figure in the first act is Gregory Solomon, a Jewish antique dealer with whom he negotiates. Solomon is played here by David Suchet and he makes the most of the role, playing up its comic potential to the full. It did occur to me that anyone who created a character like this today would be accused of stereotyping at best, antisemitism at worst; not that it is offensive, but Solomon is as much a caricature as Fagin.

Then Victor’s brother Walter arrives, and the mood darkens as their different responses to their father’s predicament are exposed and old hidden resentments are brought to the surface. Our sympathy swings from one character to the other as more of the family’s history is revealed. In a note for the original production, reproduced in our theatre programme, Miller wrote: “As the world now operates, the qualities of both brothers are necessary to it. The production must… withhold judgement… Each [brother] has merely proved to the other what the other has known but dared not face.” Meanwhile Solomon has retreated into the background. At one point the brothers actually make him wait for them in a bedroom (offstage) while they sort out their differences.

In this production Victor is played by Brendan Coyle and Walter by Adrian Lukis. I thought they were both pretty good: Miller can tilt into melodrama if overplayed, but that never happens here. From a seat near the back of the stalls I was able to follow the dialogue, in recognisable but not exaggerated American accents, without difficulty. Sara Stewart plays Victor’s wife, and at one point I did wonder whether we were in for a bit of Edward Albee-style matrimonial angst, but in fact she mostly fades into the background. John was not quite so convinced by the performances, Lukis in particular, and I agree that he did stumble over a couple of lines, but it seemed in character.

It is worth saying a few words about the almost expressionist set design. Not only is the stage crowded with furniture and bric-a-brac (including a harp and a wind-up gramophone, both apparently in working order), but a jumble of tables and chairs in a weird shade of purple (suggesting shadow?) is fixed to the high sloping ceiling. There’s a lot of clutter here; it needs clearing out. OK, perhaps the symbolism is a bit obvious. But it is very striking, and you need to fill the space somehow.

That was our Saturday afternoon. In the evening we went somewhere new, the Jermyn Street theatre, in a basement off Piccadilly. The theatre has just 70 seats. To get to the toilets you have to walk across the “stage” (no such thing here as an actual stage), and they are closed during the performance. According to Wiki this was once the changing area for the staff of a Spaghetti House restaurant.

Granville Barker is an important figure in British theatre history, mainly as a director, a collaborator with Bernard Shaw, an interpreter of Shakespeare and progenitor of the idea of a National Theatre. But he was also a playwright with a handful of fine plays to his name, including his masterpiece Waste, a political play with surprising modern resonance, which John and I saw at the National a couple of years ago.

He left a great archive of papers, and among these has been unearthed enough of the unpublished, unperformed Agnes Colander to enable a modern playwright, Richard Nelson, to assemble a performance text. There was a good article about this rediscovery in the Guardian in 2016: https://bit.ly/2F8eHvI. The theatre programme speculates, correctly in my view, that Granville Barker did not finish or attempt to stage the play because he was sure it would not pass the Lord Chamberlain’s censorship.

From this production there is no doubt that the play is worth staging, not just as a historical curiosity but in its own right. It is unpolished and somewhat underdeveloped, but it tackles a real subject with honesty and conviction. Agnes Colander, a young artist, has left her husband and is trying to make her own way. She falls in with another artist and goes to live with him, but by the end of the play she has left him too.

That’s it. Not much of a story, perhaps, but beautifully observed. The title role is played here by Naomi Frederick and I found her utterly convincing. The tight confines of Jermyn Street allow an actor no latitude at all; the closeness of the audience must be terribly off-putting. A false note, any histrionics, will be instantly detected and destroy the illusion. Frederick did not put a foot wrong. And Granville Barker deserves plenty of credit too. Agnes Colander is struggling for artistic and personal freedom in a society which will only accept her as an adjunct to a man. But she also struggles to understand her own thoughts and desires. Characters in theatre (for that matter, in film and TV too) are very often made unrealistically articulate. None of that here. As a result she seems all the more real and her struggle all the more truthful.

I also liked Matthew Flynn as her artist lover, Otto Kjoge. This is a man with no self-doubt, not much self-control and no time for convention. You can see both how Agnes falls for him and how she becomes disillusioned by his lack of understanding or empathy. The actor has to walk a fine line as Kjoge might easily become too large a character, too abrupt and passionate, for this tiny space, but Flynn just about carries it off.

The other roles are underwritten. Agnes’ other, more conventional suitor Alex comes across as wet and naïve. It’s quite hard to understand how he comes to have followed Agnes to France and impossible to believe that at the end of the play she is about to go off with him. If she does, that relationship will surely end as badly as the others; has she really learned so little? The other woman, Emmeline, is little more than a cipher, though she does tempt Otto enough to precipitate the final break-up. Harry Lister Smith and Sally Scott do the best they can with these unpromising roles. But really this is Agnes’ show, and Granville Barker’s.

——————–