Ministry of Flat Walks 24 : Arnside

23 April 2019

To follow this walk, open another tab on your browser and go to this web address: https://bit.ly/2Zv0odK.,

This was the longest walk, about six miles, of an enjoyable week. There are a couple of annoying minor climbs along the way, but they are short, no more than 50 yards in each case. John and I have done the walk once before, though he could not remember doing so. On that occasion the conditions were more favourable, as the tide was out and we were able to walk a fair distance on the sands (actually, mud) of Morecambe Bay. This time the tide was up and we had to stay on dry land.

It was a hot Bank Holiday Sunday and all the parking spaces along the waterfront at Arnside were already taken, but we managed to find a spot, almost the last one, in the little car park on the marshy land by the railway viaduct. The map shows not a car park but a public house symbol (it looks like a blue petrol pump). This car park is sometimes closed, as it is in danger of flooding if the tides are especially high; from a passing train I have seen it under water more than once. However, if you can’t find a parking spot in Arnside there are several other places along the route where you can stop.

Starting from this car park, you walk along the promenade away from the railway viaduct. The bay to your right is the estuary of the River Kent, flowing into Morecambe Bay. There is occasionally a tidal bore here – I have never seen it, but YouTube has several videos, including this one which I think is the most dramatic: https://bit.ly/2GBhejI. The bore isn’t all that high but it comes in very quickly.

The promenade continues past the end of the road and then a residential home, but gradually dwindles into discontinuous slabs of concrete, stone and pebbles. A short section is under water at high tide, but to avoid this you can turn inland and walk through Grubbins Wood.

About a mile from the start the path turns away from the sea, with a delta of marshy grass to your right, and you come to a road. The map doesn’t make clear that this is a public road with a few parking spaces which, when we came, were less crowded than the main promenade. Turn right here and you come to a group of buildings at New Barns, where there is a café and a road leads away to your left towards a caravan site.

Up to this point John hadn’t taken any photographs so I have had to source them elsewhere. All the photos from here on are his; thank you, John.

Rather than walk among the caravans, continue across the shingle on the shoreline – there is a path, although in places it is hard to discern. At first you cannot enter the woods on your left as they are guarded by a wire fence. But after a couple of hundred yards the fence retreats and you can join a path, at first indistinct but gradually becoming better-worn, through the trees.

There are no signs, so each time the path divides you have to decide whether to take the left or the right hand branch. However, so long as you have a decent sense of direction you should not go seriously wrong. You need to keep the estuary in view through the woods to your right. Alternatively, and much more easily, at low tide you can simply walk along the muddy shore all the way around Blackstone Point.

The path gradually climbs through the trees so that by the time you reach the little bay south of Blackstone Point you are on the edge of a low cliff. Take care: the footing is not totally secure, and though the cliff is not all that high, in places it is an almost sheer drop down to the shore, with nothing to break your fall if you slip.

On the map, a wriggly blue line shows the normal high tide mark, and the area to its east, appearing on the map as sand, is in fact marshland, difficult to traverse. At low tide you can safely walk across the sands outside this marshy patch. If you follow the path, at a couple of places you will find yourself on the southern edge of the caravan site which you avoided earlier.

The path continues through the woods, past the marshy bay, past Arnside Point and along to Park Point, where it climbs through the woods over a slope and back down towards the coastline, now heading east. If you have continued all this way on the shore, there are two or three places here where you can climb up to rejoin the path. Eventually you will see a stone wall ahead. The path turns left in front of the wall and comes to a broader track. Turn right through a gate. You are now on the edge of another caravan site. Follow the road through the site, turning left near the end to pass through the site entrance where there is a red-and-white pole barrier, and past a group of houses at Far Arnside. Continue along this metalled road until you come to a T junction – Arnside to the left, Silverdale to the right.

Go through the gate on the far side of this junction and on to a path which dips across a meadow, with a gate half way and a fence to your right. On the far side, up a gentle slope, is another gate, leading into another caravan site. Turn left here and follow the drive to the corner of the site where another footpath leads down a lane with hedges on both sides. We have been here before, on the Eaves Wood walk (1 April 2018), but going the opposite direction.

This lane continues for 400 yards or so and opens out on to a hillside near Arnside Tower. You will now need to scroll the map a little to the right to follow the rest of the walk.

From Arnside Tower you have two choices. The better and more interesting route is to pass the tower on its right and go downhill to join a path through Middlebarrow Wood, just along the edge of the wood. Eventually you come to the railway with paths in both directions. Turn left and cross the meadow alongside the railway tracks.

The problem with this route is that the meadow alongside the railway can become very wet. Last time I passed this way on the train, only a few weeks ago, it was almost entirely under water. I suspected that it might still be very boggy, so instead we turned left at Arnside Tower, past Arnside Tower Farm and turned right around the edge of the farm into the farm drive which leads down across the hillside.

There is a sign at the start of the drive saying No Public Right of Way, but that is not the same thing as No Public Access and I don’t think they can stop you so long as you are doing no damage. Anyway, that is the route which John and I followed – less boggy, but less interesting.

The drive eventually passes under the railway, but just before you reach the bridge you come to a pair of gates, one on either side. The right hand gate leads to the path across the meadow. Turn instead through the left hand gate – straight ahead if you came across the meadow – and follow a footpath through a small patch of woodland, into a farmyard and so back to the road.

Now follow the road back to the car park. For most of the way there is a pavement. I have to admit that this last half mile is fairly boring, but I reckon the rest of the walk makes it worth while. John didn’t agree. He didn’t like the fact that we walked through or past three different caravan sites, though in total I would reckon that they only add up to half a mile or so, and though they are not particularly exciting they are not objectionable. All three sites consist of those large caravans that are barely mobile at all – in fact I think some of them had their wheels removed. They have all been painted pale green so they merge into their surroundings, and the sites have been carefully landscaped. I don’t personally understand the attraction of cramped living spaces and chemical toilets, but perhaps if it was the only way I could get to enjoy the Lake District I would think differently.

——————–

Ministry of Flat Walks 23 : Wasdale Head

21 April 2019

To follow this walk, open another tab in your browser and input this web address: https://bit.ly/2UsT7r9.

Wow! I had no idea until a couple of days ago, when John and I completed this walk, that it was even possible. It is perhaps two and a half miles in length, flat all the way round (though in a couple of places the footing is difficult), and has instantly achieved a place among my favourite Lakeland walks.

I have always been fond of Wast Water. It is grand, remote and – for want of a better word – looming. Its remoteness means that, although it has become better known over the 50 years since I first came here, it has never been quite spoiled by throngs of people in the same way as Tarn Hows or Grasmere. And the wildness of the landscape makes the visitors, however numerous, seem insignificant anyway. We used to come to Wast Water regularly for picnics; along the road on the west side of the lake there are lots of good places to stop, with views up and down the lake and plenty of space for running around over the grass and through the bracken..

I used to think that the only thing wrong with Wast Water was the lack of opportunity for walking. Sure, it is the starting point for numerous fell walks, including a famous ascent of Sca Fell, if you are that way inclined, which I am not. And you can walk all the way around the lake if you are prepared to tackle the path across the screes on the east side. I did that once; it was quite strenuous and insufficiently rewarding in other ways. You can also walk along the road, if you don’t mind the traffic, but all you can do is return the way you came, which I always find a little unsatisfying.

A few years ago the National Trust, which is the major local landowner, constructed a bridge across the stream at the head of the lake, and on the far side opened a new camping site and car park, carefully screened from view by trees and bushes. You don’t even have to pay parking fees if you belong to the NT – just remember to bring your membership card. On the map, the car park is at the foot, just above and to the right of the lake. You can see the little blue wigwam sign indicating a camping site on the map here too.

Start the walk by returning along the drive across the bridge on to the road, and turn right. This is fell country, and on the slopes, during the summer at least, there are sheep. John and I were amused and a little puzzled to observe a long procession of them, following one another in single file, along a fellside track towards the head of the valley. They picked up stragglers from the fields along the way. It is of course a well-known saying that people follow another’s lead blindly, “like sheep” [insert Brexit reference here], but I have rarely seen the actual thing so vividly demonstrated. There didn’t seem to be anything particular attracting the sheep: but where one went, others followed.

After a quarter mile or so the road turns right on to a low bridge and crosses Mosedale Beck. Don’t go across the bridge. Instead, go through the gate straight ahead and continue along a path through the gorse bushes and across the grass on the side of the beck. Don’t go through the second gate, soon after the first, which opens on to the fell on your left. This path continues for another quarter mile, following the beck, straight at first and then bearing a little to the right. Ahead you should see an ancient packhorse bridge across the stream, and on the far side a group of agricultural buildings.

Cross this bridge and turn left, so the beck is now on your left and a new barn (I suppose it’s a barn) on your right. You soon leave the buildings behind you, and come to a junction where one path goes straight ahead up Mosedale and on to the fells towards Pillar, while the other turns right between two walls, following a tributary stream, Fogmire Beck. Take the right turn here.

I fancy that this section of the walk may be newly opened; I don’t recall seeing it on earlier maps. The path crosses the stream several times and someone (National Park or National Trust) has installed foot bridges, little more than boardwalks really, so you do not have to pick your way across stepping stones or get your feet wet. Eventually, the beck turns away to the left while your path goes right and through a gate to the group of buildings at Burnthwaite

Believe it or not, Burnthwaite has its own website (http://burnthwaite.co.uk) – it is both a working sheep farm and a B&B with what look to me like very reasonable prices. If we were not otherwise provided for it might look quite attractive. Turn right here through another gate between the buildings and on to the gravelled lane which leads back down into the valley. About half way along the lane, you can find St Olaf’s church, one of the smallest in England (https://bit.ly/2VWcSsV). John and I missed this completely and walked straight past (and I missed the tiny + sign on the map), but towards the end of the walk we met some people who asked us about it. Something for next time.

The lane emerges into the Wasdale Head car park (not the one we parked in, another one further up the valley) and so back on to the road. On the left here we found a temporary building – it looked like a portakabin, but in fact it must have been erected on site as there is no way a large cabin could have been brought by road up the valley – containing public toilets. Unfortunately they were closed, and on the wall were pasted no fewer than three separate notices, evidently placed there by different people, to apologise for the closure.

After we got home I investigated further. Apparently there is a problem with lack of toilet provision at Wasdale which is causing various … unpleasantness (you can just imagine) on the fell paths. The National Trust proposed to erect new permanent toilets at Wasdale Head, had designed something suitably environmentally sensitive and obtained planning permission, but in the face of local objections has abandoned the plan. One of the posters was from a local shop owner who obviously acknowledges the problem and was very unhappy with the local objectors. I must say I find the NT’s reluctance hard to fathom myself. Nonetheless the plan is now to rely on a new set of toilets (not yet built) back at the camp site/car park. I doubt it that will solve the problem. Meanwhile planning permission for the temporary toilets has expired; they had to be closed and will be removed shortly. This is an outcome that will satisfy no-one; I really feel that some of the people involved need their heads knocked together.

Continue along the road for a short way to where it turns right and there are two gates on the left. Go through the right-hand gate; the other leads up to the fells, and there is a fence between them. From here there is a path down the gravelly valley floor between gorse bushes and so back to our starting point.

I had thought this last bit would be straightforward, but not at all. A couple of hundred yards beyond the gate, the path emerges on to a broad strip of pebbles with no very clear features along the line of Lingmell Beck. I can’t remember enough physical geography to recall its name, and cursory online research hasn’t helped, but I am sure this gravelly surface is a characteristic feature left behind by the retreat of the glaciers, and Wasdale is a classic U-shaped glaciated valley. In any event the pebbles are rather awkward to walk across, like shingle on a beach, but from about half way across you can see where the path resumes on the far side, and from there it is easy to return to the car park.

Thanks to John once again for the use of his photographs.

——————–

Ministry of Not So Flat Walks 22 : Ulpha Park

18 April 2019

To follow this walk, open another tab in your browser and input this web address: https://bit.ly/2GsVwOY.

The route, about four and a half miles long, is only flat for about half its length. It begins and ends uphill: the final stage in particular is quite demanding and, yesterday, defeated me. But I have included it here anyway because, despite the difficulties, this is a good walk in the Duddon Valley, which has been one of our favourite places in the Lake District since Mum and Dad first came to live at Woodgate.

On the map you can see the River Duddon running from north to south towards the sea. Just to the east is the road leading up the valley from the main A595 Barrow to Whitehaven road (beyond the south edge of the map) towards the villages of Ulpha and Seathwaite. One of our favourite picnic spots is along this road, just off the map to the north, at Ulpha Bridge. David and John used to go leaping around on the rocks by the river under Mum’s watchful eye, while Dad snoozed and I read a book.

Towards the lower left of the map is another road, which also starts from the A595 and climbs towards Corney Fell. To the west of a steep hill on this road (marked on the map by >) is a Y junction. The Corney Fell road takes the lower branch of the Y. The upper branch bridges a stream at Beckstones and extends northwards along the left hand side of the map. This is in fact a narrow, twisty road, steep in places, not a useful through route to anywhere. For this walk, however, you can find roadside parking opportunities along here between the Y junction and the Beckstones bridge. That is where we left our car yesterday.

Just beyond the bridge, turn right on to a track signposted to Millbrow. This track quickly starts to climb, steadily but not too severely, with a dense pine wood to your left, a stone wall and open moorland to your right. The footing here is loose rock and gravel with a few grassy patches.

Eventually the track levels out and at the same time the moorland is replaced by a field of what look like Christmas trees, named New Plantation on the map. Ahead of you a view of the fells and the upper Duddon Valley slowly emerges, but is not fully revealed until you reach the end of the pine woods and cross a stretch of open moorland, now heading gently downhill.

To your right here are the ruins of Frith Hall (https://bit.ly/2Xo0XEC), formerly a hunting lodge, then a hostelry, then a farm, now abandoned. John of course could not resist hiking up the hillside to look at the ruins but reported back that though the location is picturesque there is nothing exceptional to see here. You might wonder who could have thought this remote place was a suitable spot for an inn, but apparently it was associated with smuggling from the Isle of Man, so perhaps being so out-of-the-way was an advantage.

The track continues downhill, crosses another bridge over a stream and passes through a gate. On the far side of this gate it divides: the left hand branch climbs over the shoulder of another hill and disappears, the right hand branch drops down towards the valley floor. You can choose either path, but we didn’t fancy another climb and so preferred to go right. The path here is deeply rutted for a while and you may prefer to stay on the grass, higher up the slope. But be careful: today was quite dry, but the ground here was spongy and damp in places, and I guess may become marshy after wet weather.

At the foot of this hill, before you arrive at the road, your path is joined by a track coming in from the right, with the stream, partly hidden behind a line of trees, just beyond. Turn sharp right here and follow this track, which proceeds gradually downhill with the stream now on your left. You go through one gate and come to a second, but the track turns sharp right in front of this gate and proceeds across the foot of a field alongside a wall. Over the wall you can see the River Duddon and the east side of the valley.

At last you have reached a section of this walk which really is flat. It’s almost impossible to miss the way ahead. John amused himself here by chasing after butterflies with his camera and eventually took this beautiful photo of a peacock butterfly which was resting on a stone wall. Patience rewarded.

Follow the track, which soon enters the pine woods, for a mile or more. There are stretches where one side or the other of the track is open to the sky, but mostly it’s just trees, and very quiet. Today the woods were carpeted with wild daffodils and, later, with bluebells, and we didn’t meet a single soul.

Eventually the path turns right, away from the river, and passes between the buildings at Beckfoot. This was probably a farm at one time, and there is still a yard with farm machinery in it, but the houses have been refurbished and I’d guess are now in use as holiday homes. There is also an attractive low bridge here over a stream.

From Beckfoot the path becomes a drive and soon leads on to the Corney Fell road. John left me here today and went on alone to collect the car, as the final section of the walk is really steep. I could have done it eventually, but only very slowly, with frequent pauses and much discomfort, and it didn’t seem worthwhile even for the bragging rights. Good for you if you want to complete the circuit. But be careful. Despite the steep gradient, people drive quickly along this stretch of road, especially after shift change at the Sellafield nuclear plant, 15 miles to the north. Many of the plant’s workers live in Barrow or Ulverston, and this road, which was never intended as a commuter route, is their quickest way home.

From the exit at Beckfoot where John left me, the road continues uphill for 600 yards or so, becoming gradually steeper until you emerge from the trees and come to a cattle grid. You are now on the open fells. Turn right at the Y junction and back to your parking place.

We did consider whether it might be a better idea to do this walk anticlockwise rather than clockwise, so as to avoid the two stiff hills I have described. But I don’t recommend it. The walk up the fell side past Frith Hall would be equally steep, remorseless and prolonged; and the footing, loose stones and gravel, is treacherous too. Clockwise is difficult in parts, but at least the steepest sections are well separated.

Thanks once again to John for providing the photographs.

——————–

Ministry of Flat Walks 21 : Hawes – Hardraw – Appersett

16 April 2019

To follow this walk, open another tab in your browser and input this web address: https://bit.ly/2GqCBUI.

One advantage of our location in Cark is that the upper stretches of the Yorkshire Dales are within reach. I’ve written previously (6 April 2018) about a walk at Dent. Today, persuaded by a weather forecast which was markedly (and, as it turned out, correctly) better for North Yorkshire than for South Cumbria, John and I set out for Hawes in Wensleydale. We have been to Wensleydale three or four times before, to the waterfalls at Aysgarth and to Bolton Castle near Leyburn, as well as to Hawes. But today our plan was to attempt a longer walk than on any of these occasions.

We left the car in the car park, which you can see on the map just south of the primary school on the west side of the town, and set off through the town centre, where it turned out to be market day (Tuesday). On the eastern side of the town we turned along a road leading north which is also the route of the Pennine Way. This road crosses the railway line, long since closed, on a bridge.

Just to the right is the old railway station, where we found a tank engine and three passenger carriages on a short stretch of track, obviously fascinating to John, though less so to me as they cannot actually go anywhere. The station buildings have been modernised and extended, and are now the Dales Museum. On another day we might have stayed to explore.

Beyond the bridge the road loops briefly to the right while a footpath, constructed of paving flags, turns slightly to the left and crosses a meadow. The path rejoins the road just before you come to a bridge over the River Ure, where I was amused to see that there is a depth indicator rising to the full height of the bridge. You can just see it in this photograph. Evidently severe flooding is not unknown or unexpected here.

Continue a little further along the road, which the map names as Brunt Acres Road (sic – I suspected a misprint, but apparently not). Before you reach the foot of the slope which you can see ahead of you, turn left through a gate on to a path which leads across the water meadows.

This path starts off as an easily visible worn track across the grass, at one point coming very close to the river on its north bank. After half a mile or so you sidestep through a gate in a stone wall and continue along the north side of this wall. The path again becomes a line of paving flags across an otherwise blameless meadow. A sign on one of the gates urges you to stay on the path as this is a hay meadow, but this claim is false, as there are sheep and young lambs grazing here. No hay will have a chance to grow while they are there.

The path bends slightly to the right, with Hardraw Beck on your left, as you enter the village of Hardraw. Just as you turn left into the road, there is a walled garden on your left, open to the public, where John and I enjoyed our picnic. The garden has become dilapidated, presumably because of lack of interest or money or both from the local parish, but at one time it must have been a charming spot. Its main virtue today was that it was out of the wind. In Hardraw you can purchase access to a path leading up to Hardraw Force, a high waterfall, further north up the beck. John and I remember our previous visit, when the grandeur of the scene was somewhat diminished by large numbers of children playing in the pool at the foot of the falls. Today we passed by.

From Hardraw, follow the road westwards, with rising ground on your right and the river well below you on your left. This road turns downhill and after half a mile or so runs into the main road down Wensleydale, the A684. Turn left here and cross the river on the road bridge, then continue to a second bridge over Widdale Beck just as you enter the village (hamlet, really) of Appersett.

From Appersett you can if you wish follow the main road back into Hawes, possibly diverting on to one of the footpaths along the south bank of the river. We, however, had more ambitious plans. Turn right directly after crossing the second bridge on to the minor road which starts alongside the beck. At the turning there is a road sign warning of a low bridge just ahead, and after a hundred yards or so you see the bridge, which is in fact a viaduct of four spans, the Appersett Viaduct, on the old railway line. It is like a little brother of the much grander, better-known viaducts nearby at Garsdale and Ribblehead, and we scratched our heads a little at the cost of this edifice on a minor branch line. John suggested that the line may not have been considered so minor when it was first opened, and perhaps he is right.

The road climbs, not too steeply, in fits and starts across the hillside, passing Thorney Mire House, a superior B&B, on your left. Just beyond the house the road takes a right-angled turn to the right, but leading off through a gate to the left is a bridleway, signposted BW B6255. Go through the gate and follow this bridleway, which is little more than a barely worn track between stone walls and across the grassy slope, around the hillside. Presently the bridleway bears right and emerges on to the B6255, the road from Hawes to Ingleton. You have another opportunity here to take a more direct route back to your starting-point.

To follow in our footsteps all the way, turn left in the direction of Hawes, but almost immediately right again through a stile on to another footpath. At this point the word path is somewhat misleading, as there is scarcely anything to indicate which way you should go. You have to pay careful attention to the map and look out for gates or stiles in the stone walls on the far side of each field, which fortunately are not too difficult to spot. After passing through a couple of these gates you emerge on to Mossy Lane, a slightly sunken lane across the hillside. Turn right here and almost immediately left again on to another similar path. The route here is harder to spot, but you should be aiming for the cluster of farm buildings that you can now see ahead.

The map shows the path here briefly emerging on to a minor road between some buildings, but we left those to one side and continued across the meadow (more paving stones here) and arriving at a gate into an alleyway among some rather unattractive modern houses. Follow this alleyway, crossing an estate road at one point, and turn left into the road which leads down from the village of Gayle, where you are now, back to Hawes and the car park.

If you like, before returning to your car you can take another footpath here, which turns right around the rising ground (on which, according to the map, the Wensleydale Creamery is situated) and down into Hawes town centre, passing the parish church, with its unusual tower-cum-steeple, on the way.

The whole walk is about five miles long, less if you take one of the shortcuts I have mentioned. Apart from the climb up from Appersett, which is not too severe or prolonged, it is very flat and easily managed. This is not the most rugged part of the Dales but there are some nice views, and Hawes is a pleasant little town with several tea shops if you feel the need to slake your thirst after your exertions. We can recommend the Bay Tree: the home-made Victoria sponge and lemon drizzle cake were excellent.

Thanks as always to John for the photographs which illustrate this blog.

——————–

Ministry of Flat Walks 20 : Derwent Water (West)

15 April 2019

To follow this walk, open another tab in your browser and input this web address: https://bit.ly/2UkcUZV. To follow the walk all the way, you will need to scroll the map northwards.

At Cark John and I are on the southern edge of the southern half of the Lake District. We do not venture into the northern half very often, and have to pick the right time to do so, as the roads get very crowded, especially at Ambleside and Keswick, and journeys can easily be prolonged. Nonetheless, today we made the effort, and drove, not without some delays, through Ambleside and across Dunmail Raise to Keswick and Derwent Water.

Keswick itself is a charming town with old buildings, narrow streets and some nice shops; but today we bypassed the main part of the town and parked our car in the long-stay car park near the theatre and the landing stage. You can see these on the map at the edge of the lake south of the town centre. John struggled with the ticket machine, which did not seem to want to accept his debit card – bring coins if you can, but be warned, the charges are exorbitant (£7.70 for five hours). Eventually he succeeded and we walked on down to the landing stage where we bought round-trip tickets for the Derwent Water launch.

There is an hourly service around the lake in either direction – I believe the frequency is increased if demand justifies, but not today. There are supposed to be seven other stops at various points round the lake, but we discovered that three were not operating today, allegedly because the level of water in the lake was too low. I suspect that the operators had other reasons, of convenience or economy, for curtailing the service. But in any case be warned. There is a website (https://keswick-launch.co.uk/status) which should tell you the day’s timetable, but today its information on which jetties were in use was quite wrong and upset my planning. Be prepared to improvise.

We took the clockwise service and spent a pleasant half hour on the lake, admiring the mountains all around. Today the views were slightly hazy, which created some pleasing shadow effects that John tried to capture on camera. I noticed that there now seems to be an off-road path along the eastern shore which we might explore on a future visit; but not today. We disembarked at High Brandelhow, which is the southernmost stop on the western shore of the lake. The map shows the route of the launch (described as Ferry, which is a euphemism) quite accurately, but unfortunately doesn’t name the individual landing stages.

This is where the walk begins. You are joining the Cumbria Way, which extends southwards to Borrowdale and into the fells, a route for more doughty walkers than ourselves. Instead, turn northwards along the well-made path which at this point sticks closely to the side of the lake. John and I last came this way three or four years ago, and in the intervening time the Lake District National Park has been at work so there is now a well-gravelled path where once there was well-trodden earth. It is as easy a walk as you could possibly desire, firm but not hard underfoot, almost completely flat and impossible to miss.

After about three quarters of a mile you will come to the next jetty, at Low Brandelhow. I suppose you could end your walk here, but that would scarcely have been worth the effort, would it? Instead, carry on along the main path, which turns inland along the side of a meadow. Alternatively you may continue along a subsidiary path which follows the lake up to a headland at Otterbield Bay before looping back, but there is no obvious advantage in this except a bit more exercise.

The main path now leaves the lake behind and climbs gently up through a gate and into woodland. You can turn right here and follow a track (black dots on the map) down to the Hawse End jetty. Today it turned out that this was the last stopping point for the launch before returning to Keswick, but we did not fancy curtailing our walk so soon, and decided instead to continue around the lake. The main path continues a little away from the shore, briefly joining a metalled minor road past an outdoor activities centre. The road, however, soon turns away and the path continues onward, briefly downhill, across a meadow and back into woodland on the far side.

Presently you come to the Lingholm Estate (https://thelingholmestate.co.uk), a former Victorian mansion and grounds which have been converted into self-catering accommodation. In the adjoining meadow was a small group (herd? flock? gaggle?) of alpacas, which had attracted the attention of several other walkers beside ourselves. Alpacas still seem a little exotic in these surroundings, but they are an increasingly common sight in the Lakes and are amusing, placid beasts. The timetable for the Derwent Water launch lists a stop at Lingholm but today it was closed.

Just past the entrance to the estate, the path divides. A broader track turns gently downhill to the right; a narrower path, uphill, continues straight ahead. We chose the broader track, a slightly longer route (according to the map) but more comfortable. This leads to a metalled road and then to a small marina at Nichol End. My original plan had been that we would return to Keswick by launch from here, but this jetty too was out of service today.

The rest of the walk is less attractive, and much of it is along roads, but not without interest. After Nichol End you join a minor road – which if you followed it southwards would eventually lead you over the Newlands Pass to Buttermere – into the village of Portinscale. There is not much traffic, and for most of the way there is a pavement, first on the right, then on the left. Approaching the centre of Portinscale you will come a large café on the left and then a T junction, with the road turning to the left and a lane to the right. Follow this lane, which passes the Derwentwater Hotel on its right. The lane quickly reaches a dead end for motor vehicles on the bank of the River Derwent, but for pedestrians there is a suspension bridge, sturdy enough that John could not make it sway however hard he tried. This must surely once have been the route of the main road through Portinscale, but there is no sign now of whatever road bridge used to be here.

After crossing the bridge the road resumes, but within a hundred yards or so there is a well-made path turning off to the right between two wire fences across a meadow. We passed a lot of pedestrians here, and I guess it is the established route for workers, shoppers and schoolchildren from Portinscale to Keswick, a 10 minutes walk or so. The path emerges on to the road next to the bridge over the River Greta on the edge of Keswick town centre.

Turn right across the bridge, then right again after another 100 yards or so, and follow this road round for another quarter mile until you come to the mini-roundabout where the road leads off to the right down to the long-stay car park from where we started and the main landing stage. The total length of the walk is, I’d guess, a shade under 5 miles, but you can cut it short at any of the jetties along the route, Just remember to check first whether the jetty is in use that day.

Thank you to John for the use of his excellent photographs.

——————–

Blade Runners

10 April 2019

When the film Blade Runner 2049 was released a year or so ago Georgina and I very much wanted to see it, but somehow we never managed to find a mutually convenient date, and missed the opportunity. Now Georgina has given me a DVD of the original (1982) movie, and I have borrowed BR2049 from the Cinema Paradiso DVD library. So I have been able to watch the films on consecutive nights, albeit only on my large-screen TV and not in the cinema. I’m glad I had the opportunity to do this. BR2049, though undoubtedly a sequel, stands well enough on its own. But neither film is altogether easy to follow: quite a lot of the dialogue is elliptical and you have to work to keep up. It definitely helps to watch them together.

Let’s begin with a brief explanation, in case you have been living in a cave. Replicants are artificial humans, products of bioengineering. They can be employed to do dangerous or uncongenial tasks that humans don’t want. But sometimes they go rogue. When they do, blade runners are the agents dispatched to track them down and kill them.

I saw the original BR in a cinema soon after its release. Like most audiences, I remember being amazed by the visuals. I had read my share of dystopian science fiction, but this was the first time I had seen it brought so vividly to screen. The novelist William Gibson is widely credited with the creation of the cyberpunk genre, but BR predates Gibson’s seminal first novel Neuromancer by two years.

Watching again now, even on my TV screen, I am still awed. The opening image, of a seemingly endless grey metropolis, with great gouts (unexplained) of flame erupting randomly skywards, is stunning. The famous scene in the neon-lit outdoor market with rain bucketing down is equally memorable. It always seems to be raining in BR, though whether this is symbolic or merely for atmosphere I am not quite sure. I had forgotten the grotesque figure of genetic designer J F Sebastian and his household of automatons, but he too has this ambiguous quality: symbol, or just creepy?

BR is also remembered for Harrison Ford as the blade runner Deckard. Ford was already a star from his appearances in Star Wars and Raiders of the Lost Ark, but this is a role with a good deal more dramatic heft, following the footsteps of other great noir protagonists like Bogart and Mitchum, though Ford’s lack of affect also puts me in mind of Eastwood.

The film’s subtext explores ideas of what it is to be exploited, and to be human. Fans apparently spend a good deal of time debating whether Deckard is himself a replicant, and interestingly the makers of the film themselves seem undecided on the point (which BR2049 does not resolve). Honestly, I don’t care. The ambiguity serves the film well.

It is just as well that BR has subtext, because viewed purely as a film noir it has a pretty sketchy plot. The protagonist is tasked with tracking down a group of outlaws, and does so. That’s pretty much it. None of the reversals or double-crosses typical of the genre. It is design and atmosphere and ideas, and I suppose Harrison Ford, which make this a film to remember.

No such complaint about BR2049. The film is set thirty years later but takes the final events of BR as its starting-point. I do not want to be any more specific than that, because you may not yet have seen it and I don’t want to give away any spoilers. The protagonist here is K, a blade runner who is himself a replicant. K is played by Ryan Gosling, whom I last saw in the very different La-La Land – see my first ever blog, on 17 January 2017.

I may as well admit that I didn’t find him totally convincing here. Where Ford is deadpan, Gosling is lugubrious, which doesn’t seem to work so well. You can, however, believe very easily in his doggedness: he is determined to find the answers even though he suspects they may cost him dear. He finds himself in possession of information whose significance he gets to understand only gradually, and which two other factions are also seeking. I found the clues here a little easier to follow than in BR, but there was still at least one revelation which came as quite a shock.

Harrison Ford also turns up (not a spoiler – he is in the opening credits). When he first appeared I thought he was going to give a phoned-in crazy-old-geezer performance, but he quickly gains depth and his final scene is genuinely touching. I wouldn’t say he acts Gosling off the screen, but even at 77 he has the charisma that the younger man lacks.

However, BR2049, like its predecessor, is ultimately not about the performances but the visuals and the ideas, and it doesn’t disappoint. The environmental degradation that was mostly implied in the earlier film is here highly visible. There are no exposition scenes as such, but from scattered references in dialogue we learn that there has been a complete collapse of ecosystems. An important character makes his money from protein farming – a euphemism for breeding maggots. At some point in recent history there was a nine days’ blackout when all power failed; and Ls Vegas has been devastated by a nuclear explosion, though whether by weapon or accident is nor made clear. Landscapes are barren earth and rubble. One character says they have never seen a tree; the only tree in the film is dead (and, I’m sure, symbolic). BR2049 won Oscars for cinematography and visual effects, among many other awards. Perhaps it has no single image with quite the impact of BR’s market scene, but it offers a whole range of memorable images making up what one critic has called “a future world breathtaking in its decrepitude, a gorgeous ruin.”

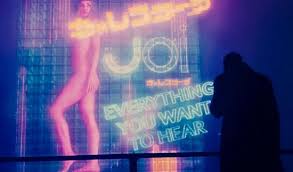

BR2049 offers one entirely new futuristic concept, and that is K’s live-in companion, an artificial intelligence embodied in a 3D hologram, called Joi. She is a commercial product, and initially she behaves much as you would expect, supportive and submissive. Of course since her presence is only an image she cannot touch or be touched, and this leads to one very creepy yet curiously emotional scene later in the movie, which I will not describe further for fear of spoiling the effect. If you watch the film you will know exactly what I am talking about.

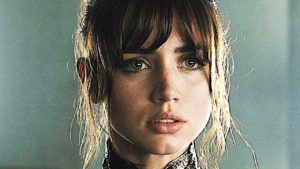

As the film proceeds Joi (played with devastating conviction by Ana de Armas) develops agency of her own, showing increasing awareness of K’s dilemmas and culminating in a very human-seeming act of possible sacrifice to protect him. Whether this is very smart programming of her AI or shows evolution beyond it (in the same way as replicants have evolved beyond their programming), the implications are significant. Are we all programmed for self-interest? Is it a sign of true self-awareness to be able to rise beyond that? What if our creations show that same capability? The original BR raises similar questions, but Joi’s presence adds a further dimension. I don’t think it is an accident that the most sympathetic character in the film is also the least “human.”

BR2049 has been criticised in some quarters for its apparent misogyny. The critic who complained that all the film’s women were either prostitutes, holographic housewives or victims was just plain wrong: two of its most significant figures, one (presumably) human and one replicant, are female. But it’s true, and clearly intended, that the film’s imagined world is, well, sexist. Another critic seems to me to be nearer the mark, writing: “The movie is about secondary citizens. Replicants. Orphans. Women. Slaves. Just by depicting these secondary citizens in subjugation doesn’t mean that it is supportive of these depictions.” BR2049 is set in a world of exploitation and prejudice. All SF dystopias are in some way Awful Warnings, and this one is no different.

Despite its award-winning credentials BR2049 was not a great hit with audiences. Though there are some brutal action sequences, its overall tone is thoughtful, elegiac and downbeat. It’s also 163 minutes long. But I couldn’t detect any padding: a few seconds could no doubt have been snipped out here and there, but I can’t think of a single scene that is unneeded. BR2049 doesn’t quite have the novelty or impact of the original BR. It requires patience, and Gosling can’t match up to Ford. Just the same, I found it a much more engrossing movie.

——————–

Brexit, again

8 April 2019

Friends in the choir where I sing have started asking me, as a former civil servant, what in my “expert” opinion will happen next in the endless drama that is Brexit. My usual response is to throw up my hands and say that I haven’t a clue. That is true, so far as it goes, but I am starting to think that it isn’t enough.

No matter how we got here. No matter all the lies and subterfuges and misrepresentations and arrogance and bluster and sheer outrageous illegality. We are where we are, and though I can’t say what will happen next, I know what I think should happen.

But first, what shouldn’t happen: a no-deal Brexit. There seems to be a majority in Parliament against this at least, if for nothing else. The backbench Bill introduced by Yvette Cooper and Oliver Letwin will probably pass Parliament this week, forcing Theresa May to accept whatever offer the EU is prepared to make on a further extension of Article 50 rather than allow a no-deal outcome. It is notoriously difficult to read May’s mind, but I think there are signs that she too has at last realised that no deal cannot be countenanced. Perhaps the 14-page no-holds-barred briefing provided to the Cabinet this week by Mark Sedwill, head of the Civil Service, has had something to do with that.

The greatest threat in this respect is not Boris Johnson or Steve Baker but Emmanuel Macron, as it is reported that he just wants the UK to leave with no further delay, with or without a deal. Fortunately there are other influential voices in the EU, notably Angela Merkel and Donald Tusk, who see things differently, and I think they will persuade Macron to allow more time.

Of course, if the EU insists – as it well might – that the price of further delay is UK participation in the European elections, due at the end of May, it will precipitate fury and outrage among the Tories beyond anything we have seen so far. Theresa May might well be a casualty; and if, as seems quite likely, the Tories end up with a hard-line Brexiter as their next leader, he or she may well not survive a vote of confidence in Parliament, precipitating a general election. And so there will be further delay without any guarantee, even after an election, that any party (let alone any vision of our future relationship with the EU) will command a stable majority. We could end up six months from now and be no further forward. Which is a further reason why we badly need some indulgence from our EU neighbours.

However, all this, however momentous, is still a side issue. The central issue remains: what deal can, or should, be made? So far Parliament has failed to find an answer. One reason why May has been so stubborn in pressing for her own deal against all the Parliamentary odds is that she is right about this at least: it is the best deal that could have been made which addresses all the substantive reasons why people voted Leave in the first place. It curbs EU immigration, it removes us from the sway of the European Court of Justice (though not the European Court of Human Rights which is not an EU institution), it allows us to make our own laws different from the EU when it pleases us, and it allows us to pursue our own trade policy. You may disagree that these outcomes are worthy, or worthwhile at the price, but the deal faithfully delivers the outcome of the referendum.

However, the deal has not found favour in Parliament. All the other viable alternatives which were paraded during Parliamentary debates over the last weeks involve sacrificing one or more elements of the deal in order to reduce its impact in one way or another. (I say viable because the Malthouse compromise, and other similar proposals to sidestep the Irish backstop in some way, are not viable: they will never find acceptance with the EU.)

The Norway option, leaving the EU but rejoining EFTA, would keep us in the customs union, allowing free travel within the EU (to everyone’s relief) but at the price of no independent trade policy. Since the independent trade policy is a chimera anyway, certain to leave us at the mercy of the rapacious USA and China, it is no surprise that this option has more Parliamentary votes than May’s deal, though still not a majority.

The Common Market 2.0 proposal would keep us in the single market as well as the customs union. The additional price would be that we would have to allow freedom of movement, though many employers, not least the NHS, would be mightily relieved. The idea of this option is that it would avoid the encroachment of EU competence into other areas of government – the ever-closer union. Parliament also favours this option over May’s deal, though it still cannot command a majority.

And third, there is the option of a second referendum, a People’s Vote. I do not understand why this is seen as an alternative: it is, strictly speaking, an add-on. Whether it is the May deal or Norway or Common Market 2.0, or some other compromise, it can and in my view should be the subject of a further referendum. I do wonder whether it is a combination of one of the sub-May compromises with a second referendum that might ultimately clear the deadlock. My own preference would be for a referendum pitting May’s deal against Remain: for the reasons above I think May’s deal comes closest to delivering the outcome of the 2016 referendum, and so would be least open to objection. But, given the margins by which MPs have voted against May’s deal, I doubt whether Parliament would accept it as an option for a People’s Vote. It has been too soundly rejected.

The objections in principle to a People’s Vote seem to me quite wrong. There is no law or principle or expectation that the outcome of a referendum held three years ago holds good indefinitely. We have elections every five years (at least) and frequently change our minds about who should form our government. The referendum expressed support in principle for a policy to be pursued; but now we know what it will entail (which we certainly did not know at the time) it is common sense that we should have a chance to endorse or reconsider our earlier preference. A commentator on the radio pointed out that this is quite a common pattern in industrial relations: a trade union ballot endorses strike action, and there is then a second ballot once a detailed settlement has been worked out. This seems to me quite a good parallel.

I greatly regret that Remainers and soft Brexiters have allowed this argument to go by default. The idea that it is somehow undemocratic to hold a second referendum has not been challenged as strongly as it should have been. It seems clear that Brexiters are not confident they would win a second referendum, hence their passionate resistance. Otherwise they ought to welcome the idea. A second vote for Leave would settle the issue for a generation. There is nothing else that will have that effect. With 6 million names on a petition to withdraw Article 50, and a million people parading for Remain in London a fortnight ago, there is no chance that the issue will go away, even if we leave without a deal at the end of the coming week. Efforts to reverse that action will simply be intensified. But they would be quietened by a second vote for Leave.

I have heard otherwise sensible people argue that a narrow victory, especially for Remain, in a second referendum would be bad for public confidence in our democracy. I don’t understand this at all. How can conducting a referendum be bad for democracy? It is true that the issue of the UK’s relationship with Europe seems set to be the defining political issue of our times, with strong opinions on both sides and much public disquiet, often egged on by people who should know better. But that is true anyway, with or without a People’s Vote. We are facing turbulent times in any event. The one thing we must not do, though the temptation is strong, is to close our eyes and ears and wish it would all go away. Silence is a betrayal; which is why I no longer think it is enough to throw up my hands and say I don’t know.

——————–

Fantasy General

7 April 2019

OK, I know. Feedback is consistently that whatever I write about computer games is less interesting to my readers than pretty much anything else. That’s a shame, but I refuse to be cowed. I like games, and a picture of my life wouldn’t be complete without them. I suspect that some of you may suffer from a mistaken idea of what computer games are all about. Most media reporting about computer games is sensationalised, superficial and just plain wrong.

Not all computer games are lurid or violent. They do not induce antisocial behaviour (see https://bit.ly/2UApys2 which cites primary research). They are not played mostly by spotty nerdish teenage boys in smelly bedrooms. They can scarcely be described as a minority pursuit: according to reliable online statistics (https://bit.ly/2KdXkiB), in the first quarter of 2018 there were 23.1 gamers in Great Britain. That is a little more than one third of the total population.

That said, I doubt whether, over the last three months or so, more than a couple of hundred others have been playing the game that has occupied my attention: Fantasy General, which was first published in 1996, pretty much the Dark Ages of the gaming world. Most computer games typically have quite a short lifespan: the continuing advance of computing technology means that most older games are quickly forgotten. But there are exceptions, and judging from online comments I am not the only player to find FG still worth their time and attention.

Older games have some advantages which many more recent games lack. The limitations of computer technology in the pre-broadband era made online play more or less impracticable, so games had to be designed for the solo player. By contrast, many of the most recent games are designed for online play and the solo option, if present at all, is weak. In the 1990s computer graphics were still in their infancy, so it was not possible for game companies to use flashy video to conceal deficiencies in the game itself. Many of the game designers had graduated from board gaming and were focused on actual gameplay, including the development of a worthwhile computer opponent. They also knew the value of clean presentation without unnecessary frills.

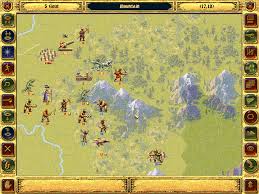

FG is a game of fantasy warfare in which you represent a freedom fighter leading a popular rebellion against the Shadowlord, who, like all Dark Lords from Sauron onwards, cannot quite grasp that his power is under threat. A campaign consists of a long series of scenarios, of increasing size and complexity: the first will take barely ten minutes to play, but the longest and most challenging may take three or four hours. Each scenario takes place on a different map, divided into hexagonal spaces (hexes) in a manner familiar to board game players. The hexes show different terrain types, each of which has a distinctive effect upon combat and/or movement. The graphics for terrain and units are admirably clear and uncluttered.

You have to win every scenario in order to win the campaign, while the Shadowlord only has to win once in order to defeat you utterly. You also need to increase the size of your army and the strength of your individual units, which carry over (if they survive) from one scenario to the next. You earn gold from your victories, which you spend to buy new units and to research better units; at the same time your existing forces are gaining experience in battle which improves their strength and defence.

So the game designers have given the AI two specific modes, varying from one scenario to another. There is a turn limit for each scenario, and in some of them the AI is set up to fight defensively: if it can prevent you from securing your victory goals (typically, to capture three or four key objectives on the map) within the turn limit, you lose the scenario and the campaign. In others the AI fights aggressively, aiming to damage your forces as much as possible in order to weaken your army for later in the campaign.

In some scenarios you already hold one or more victory locations at the start, but need to capture others. The computer is smart enough to try to sneak units past your advancing front line in order to capture your undefended heartland. That’s pretty good for a 1990s AI.

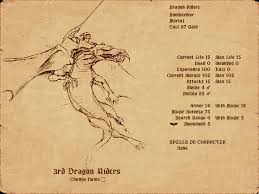

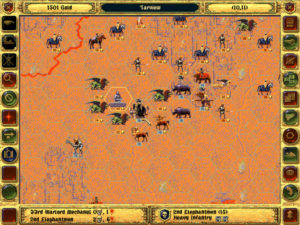

The essence of gameplay is that combat takes place whenever an attacking unit enters a hex occupied by an opposing unit. There are ten different classes of units – heavy and light infantry, heavy and light cavalry, archers and so on. Each has different and quite distinctive qualities in attack, defence and movement. They also function differently on different types of terrain. Thus, for instance, heavy infantry have the best overall strength and defence, and they alone are able to defend against cavalry charges, but they are very slow, especially on heavier terrain. Light infantry are weaker, but they are more effective on rough terrain, and move more quickly across all terrain. Cavalry are the best attackers in the game on open ground, and they move quickly (though less so on rough terrain) but they are less strong in defence and vulnerable against aerial attack and archers. Archers are relatively weak and slow, but because they attack from a distance they are not vulnerable to counterattack, and unlike infantry and cavalry they can directly attack aerial units.

Combat results are not preordained, but are determined randomly within a range which is set by comparing the strength and defence of the opposing units. Most units have 15 “lives” which are gradually whittled away in combat but may be restored by resting or recruiting in friendly locations. Each unit also has a morale rating which determines its propensity to retreat. A major part of gameplay is understanding when a unit is likely to retreat, since a planned series of attacks can force a unit to move several hexes away from its starting location.

For all the fantasy trappings, FG is not wholly unlike chess. The large hex-based battlefields, the semi-randomness of battle results and the terrain effects on movement and combat are obvious differences; but, as in chess, success requires forward planning and using the different types in combination to maximise their strengths. Sacrificial plays can draw out a dug-in opponent, and traps can be laid for an over-ambitious attacker.

Given its provenance, FG really only has one deficiency which I think is partly due to its age. For a fantasy game, the magic element is weak. There are magical artifacts which can be retrieved, most of which serve simply to improve the combat effectiveness of the unit which carries hem. (One artifact per unit.) There are also a handful of spells which may be wielded by leaders or individual units, but except for the healing spells they are underpowered. Essentially this is a semi-abstract battle game with fantasy trappings.

Over the years I have made several attempts at playing the main campaign in FG, but this is the first time I have stayed the course. The game isn’t especially difficult – actually the difficulty is adjustable; you can choose to play as one of four different leaders (such as Mordra, illustrated here), each of whom has their own advantages and disadvantages. You can also vary the difficulty by giving the AI more resources to buy units and starting its units off with more experience so they are tougher. I set the difficulty level for this campaign just above half-way up the scale, which was quite hard enough, thank you; by repute FG at maximum difficulty is a severe challenge indeed.

But, at whatever difficulty level, the game requires stamina, and though you can take a break between scenarios, if you leave it too long your interest is liable to fall away. In January this year I started a new campaign, taking advantage of the fact that I would be at home most of the time until Easter which is relatively late this year, and so wouldn’t lose the thread as has happened with all of my previous attempts. Having at last finished the campaign I do definitely feel a sense of satisfaction.