Tristan and Yseult

23 June 2017

Georgina and I went on Wednesday to the Globe Theatre in London to see Tristan & Yseult in a touring production by the Kneehigh company. It was a glorious day, in fact sweltering – the Globe theatre staff handed out free bottles of water to the audience as we went in. There was some aircraft noise, though I’ve been at the Globe when it was much worse, and thankfully there were no helicopters. Georgina had not been to the Globe before and I think she enjoyed it, though the backless seats in the lower tier took a bit of getting used to, as did the hired cushions which provide some comfort on the wooden slatted benches.

T&Y is Kneehigh’s signature production and has brought them international acclaim. I confess that I didn’t really know what to expect. But Georgina seemed really keen when I tentatively suggested we see the show, so off we went. And on the train home, and since, I have been trying to work out what I felt about it.

First, the good points. There is a lot of movement in the show and I think that’s what I enjoyed the most. Some of it is dance, in a variety of styles, from street dance to something approaching ballet: the choreography is outstanding, fluid and never forced. Some of it is closer to mime, as in silent films where action takes the place of words.

The principal performers did full justice to the material. They were all excellent, but none more so than Hannah Vassallo as Yseult. It came as no surprise to find that she is a graduate of the Rambert School of Ballet and Contemporary Dance. Of all the cast, it was she whose movement was most expressive – desperate when first claimed as a trophy of war, infatuated with Tristan, torn between him and Mark, remorseful when Mark takes her back, desperate again when she returns to Tristan too late. A word should also go to Kyle Lima as Frocin, whose jealousy of Tristan sets the tragedy in motion. His initial break dance, and the later scene when he spies on Tristan and Yseult, are beautifully performed in totally contrasting styles.

The storytelling is admirably clear. For me, the story of Tristan is familiar, from the Arthurian legends I read as a boy as well as from the Wagner opera, which in fact differs in significant details. But anyone not knowing the story – and there is no plot synopsis in the programme to help them – should have found it easy to follow. One or two details are left unresolved: in particular, the figure of Yseult’s maid Brangian (camply played by Niall Ashdown), who crafts the fatal love potion, remains a mystery. But it doesn’t really matter. Nor does the incongruity of seeing King Mark of Cornwall dressed in a modern business suit. Apparently the original brief to the writers was to steer clear of anything medieval which would get between the audience and the story, and it works. More importantly, the whole story which Wagner takes five and a half hours to tell was completed in barely two and a half hours, including the bits that Wagner leaves out. The show certainly does not lack pace.

The storytelling is admirably clear. For me, the story of Tristan is familiar, from the Arthurian legends I read as a boy as well as from the Wagner opera, which in fact differs in significant details. But anyone not knowing the story – and there is no plot synopsis in the programme to help them – should have found it easy to follow. One or two details are left unresolved: in particular, the figure of Yseult’s maid Brangian (camply played by Niall Ashdown), who crafts the fatal love potion, remains a mystery. But it doesn’t really matter. Nor does the incongruity of seeing King Mark of Cornwall dressed in a modern business suit. Apparently the original brief to the writers was to steer clear of anything medieval which would get between the audience and the story, and it works. More importantly, the whole story which Wagner takes five and a half hours to tell was completed in barely two and a half hours, including the bits that Wagner leaves out. The show certainly does not lack pace.

The music and musicians were very good, as they need to be in a show which makes so much use of them. I particularly admired the way that recorded and live sound were seamlessly blended; it’s not an easy thing to do. The show began and ended with Wagner, but in between we had live versions of Only the Lonely, Every Breath You Take and a good deal else that I didn’t recognise. There was also deafening rock music, complete with heavy beat and screaming guitars, to accompany the battle scene when Tristan comes to Mark’s aid in defeating the Irish invader Morholt. That was very effective. I did however think that elsewhere in the show there were slightly too many nondescript songs interrupting, rather than underscoring, the action. Perhaps they provided time for costume changes, or simply for the cast to get their breath back.

I also enjoyed the show’s sense of humour. There is not much comedy at the Round Table, except for the boorish Sir Kay (who anyway comes good in the end). And there is even less in Wagner. But Kneehigh’s T&Y is quite often funny, without ever resorting to cheap or smutty gags, to slapstick or to puns. Some of the humour is in action, as when Brangian gives Yseult two bottles, one of wine and one of love potion, that are effectively identical: you can see what’s going to happen. Some of it is wit, as when Morhaut talks up his own Ireland and denigrates Cornwall. Some has clearly been rewritten to keep it up to date – there was the obligatory Brexit joke for what I’m sure was a Remainer audience.

In a nutshell, everything in this show is calculated to communicate easily with its audiences, not just regular theatre-goers but anyone at all. The story is clearly told, the language is simple, emotions are recognisable, the dance is spectacular, and there are jokes. No wonder it has been a hit. I only detected one false note and that came right at the end, when the final minutes of Wagner’s opera (orchestra only) are played to accompany Tristan’s death and Yseult’s return, just too late to see and possibly save him; instead, she dies from grief. There’s nothing wrong with borrowing a bit of Wagner. But this music is saturated with doomed romanticism, and is a poor match for T&Y’s breezier, primary-colours quality. Borrowing the music is one thing; borrowing the emotion which it conjures is a bit cheap.

Given the nature of the show it seems pointless to complain that there is no character development. The principal figures are scarcely characters at all, but archetypes. They convey emotion, and you can empathise with their feelings and dilemmas, but they don’t seem real. Only Yseult, who finds herself loving two men, shows much individuality, and I suspect that is thanks to Hannah Vassallo’s performance.

It may also be a little unkind to complain that the script, written to be accessible and plain, is no more than serviceable. Much of it is written in rhyming verse, in a variety of forms to match character and circumstance; for instance, only King Mark speaks in iambic pentameters. But rhyme is treacherous, and rhyming verse isn’t necessarily poetry. I did not detect much that was poetic about the script. It is just as well that the spoken word is only a relatively small part of the show.

But these are quibbles. The aspect of the show with which I was least satisfied was more fundamental: the framing device which is used in a similar way to the chorus in Greek drama, to introduce, comment on and facilitate the drama. T&Y begins with a neon sign backstage, Club of the Unloved, and with a number of anonymous figures, dressed in balaclavas and anoraks (they must have been most uncomfortable in the heat) and wielding binoculars, on stage. They are members of the Club, and are described as Love Spotters, as in bird spotters (twitchers) – their costume is plainly a parody. They are led by a woman dressed in an elegant all-white outfit, named in the programme as Whitehands, whose true role in the drama only becomes clear late in the show.

But these are quibbles. The aspect of the show with which I was least satisfied was more fundamental: the framing device which is used in a similar way to the chorus in Greek drama, to introduce, comment on and facilitate the drama. T&Y begins with a neon sign backstage, Club of the Unloved, and with a number of anonymous figures, dressed in balaclavas and anoraks (they must have been most uncomfortable in the heat) and wielding binoculars, on stage. They are members of the Club, and are described as Love Spotters, as in bird spotters (twitchers) – their costume is plainly a parody. They are led by a woman dressed in an elegant all-white outfit, named in the programme as Whitehands, whose true role in the drama only becomes clear late in the show.

I’m afraid I thought this a misjudgement. The audience is already being asked to accept the essence of the story without being distracted by the incongruities of dress or set or music or language. But the Love Spotters are an insistent distraction. Who are they? What role do they have in the story? Greek choruses were anonymous, which gave them freedom to fulfil different roles in an unfolding drama. Giving T&Y’s chorus such a specific identity removes that freedom. Giving them the identity of the unloved, in a show whose entire story is about doomed love, seems perverse, notwithstanding the story’s final twist. And dressing them in parody costumes trades consistency of style for a cheap joke.

The funny thing is that Georgina didn’t seem worried by this at all. She saw they were functioning as a chorus and wasn’t put off by the incongruity. I guess we all have our sticking points at which we are no longer willing to collaborate with the necessary compromises of stage production. It seems that Georgina’s is in a different place from mine. Still, we both enjoyed our evening out.

——————–

Madrid : Toledo and Segovia

18 June 2017

(See below for my first two blogs about our trip to Madrid.)

John and I made two day trips from Madrid: to Toledo, with David, Sue and their friends, and to Segovia, on our own. In each case we travelled on the smart new high-speed trains operated by Renfe, the Spanish national rail company.

The train to Toledo leaves from Atocha station, not too far from our apartment, and covers the 46 miles in just 30 minutes. Since the high-speed line was opened, Toledo has in effect become a commuter town, with hundreds travelling by train to work in Madrid every day, though their cars (which we saw standing in the station car park) must be like ovens by the time they return.

The journey is interesting, not just for the rail enthusiast or economist but for the views across the open countryside south of Madrid. The land, at least at this time of year, is an ochre colour, somewhere between yellow and brown, dotted with buildings and, here and there, groves of trees. I suspect these are olives, which tolerate drought well, rather than oranges or other fruits which need more water, as there is little sign of systematic irrigation. Several of the buildings are ruins, enough to be a noticeable feature. It is probably easier to start afresh than to attempt to rebuild on site; there is, after all, no shortage of land.

Toledo station is itself a fine building, inside and out. According to Wiki it has been declared a Property of Cultural Interest and classified as a monument. But the old town of Toledo stands on top of a hill while the station lies at the foot, so, after the obligatory railway photographs, I carefully selected a route up to the town centre which appeared to have the gentlest gradients. This turned out to be a good idea for other reasons too. We crossed the Tagus River on the new road, which gave an excellent view of the Roman Puente de Alcantara, and climbed up to the town centre through city lanes some way off the main tourist routes.

The streets of Toledo reminded me of the Greek islands which I visited many years ago. They each have plain-walled buildings with small windows and are separated by narrow lanes. True, the island buildings are usually white, whereas Toledo shares the same ochre colouring as the surrounding countryside. But the feel of a community seeking collective protection from the burning Mediterranean sun is very similar. In several places Toledo’s residents have strung canvas sheets at roof height across the lanes to provide extra shade – a good, simple, low-tech idea, though not so helpful for photographers.

Our main objective in Toledo was to view the historic buildings, and they are certainly striking, in a mixture of styles reflecting the town’s history as a melting-pot for different cultures. We went first to the Cathedral, a massive Gothic edifice built over several centuries. Hemmed in by the narrow streets, it’s quite difficult to get a good overall idea of the building from the outside, but the interior shows the Gothic style in full flower with its high columns and pointed arches. There is also some fine stained glass, mostly in the high windows.

Around the cathedral interior are a series of chapels dedicated to various saints, each with its own altarpiece, some of them being very rich and ornate, several also decorated with fine art including paintings by Goya and van Dyck. On display among other treasures is a remarkable gold and silver object called the Great Monstrance of Arfe, which houses a smaller monstrance (also gold and silver) used to parade the Host on certain holy days. I have to say this object made me feel rather uncomfortable; whatever your beliefs, does God really demand all this ostentation?

Our guidebook took us to several other buildings, but we were disappointed to discover that the El Greco Museum was closed. John is almost as keen on El Greco as he is on Goya, and the El Grecos that we saw elsewhere in Toledo certainly show him to have an interesting, distinctive style and approach, with their narrow faces, sharp jaws and deep-set eyes. Elsewhere the buildings were as interesting for how they illustrate Toledo’s multicultural history as for their architecture, though the grey stone walls of the Monasterio de San Juan de los Reyes (St John of the Monarchs) and their elaborate architectural detail stand in contrast to the rest of the town. We also visited the Museum – more El Grecos but not too much else of general interest.

Toledo has an enduring reputation for the manufacture of steel, especially blades. The tourist shops had a large display of replica swords on display (I tested one; they were blunt) in a wide range of different shapes and sizes – long or short, curved or straight, broad or narrow, single or double edged, smooth or serrated. I had been considering whether to buy one as a souvenir, but came to my senses just in time. John and I did however buy various other souvenirs in Toledo, including decorated ceramics and metalwork.

A couple of days later we travelled to Segovia, this time from Chamartin station in north Madrid. This was also a high-speed service, covering 43 miles in 28 minutes, but we were disappointed that much of it was through the 17-mile Guadarrama tunnel under the sierra north of Madrid. We were also disconcerted to find that Segovia’s high-speed rail station is a characterless block 5 miles from the town, so we had to complete our journey on the connecting bus service, though this at least meant that we did get a brief look at the countryside and the mountains.

Segovia’s principal feature is the magnificent double-arched Roman aqueduct, built of unmortared granite blocks.

It is a recognised world monument and a testimony to Roman engineering skills, though I do wonder how many slaves died from accidents or heat exhaustion during its construction. John explored it at ground level (you cannot walk across) from end to end while I rested my feet, but really it is the central section with the double arches which makes it so special. We wondered whether it qualifies as one of the seven surviving wonders of the ancient world, but perhaps it is narrowly beaten to that honour by another Roman aqueduct, the triple-arched Pont du Gard, in southern France. Nonetheless, Segovia’s aqueduct was probably the single most striking building we saw all week.

Segovia’s town centre has the same yellow-brown colouring as Toledo’s, but I thought I perceived an interesting difference in style. Segovia, to me, felt more Italianate, with a good deal more decorative ironwork at the windows and doors. There were however the same narrow, winding alleys. It was easy to imagine Spanish bravos with blades bared, feathered hats and swirling cloaks, pursuing some rival up and down the lanes.

We visited the cathedral (again, Gothic) and were disappointed by the museum (closed), but also walked out to the far end of the town to see the Alcazar in its imposing position overlooking the confluence of the Eresma and Clamores rivers.

The Alcazar was partially rebuilt in the 19th century after a fire, but in authentic style, and it gives a good feeling of the impregnable mediaeval fortress it once was. On display was an interesting collection of weaponry, including several complete suits of plate armour – a welcome diversion from artworks and architecture. No doubt the armour gave its wearers solid protection, but it must have been hellishly hot and heavy to wear.

On our way home from Spain, last Thursday, John and I arrived at Gatwick on a warm evening (22º or so). People were saying it was hot, but we knew better. We caught the train north from Gatwick to East Croydon, and felt renewed affection for the green rolling countryside. Then at East Croydon we found that two successive trains to Oxted were cancelled and we had to wait the best part of an hour for the next. I wouldn’t swap our countryside, or our climate, for Spain’s at any price, but I’d swap our commuter trains for theirs in a heartbeat.

Many thanks to John who provided most of the pictures for this blog. Those for my other Madrid blogs came from public sources.

——————-

Madrid : Art

18 June 2017

(See below for my first blog about our trip to Madrid.)

Madrid has some of the finest art in the world on display, and John and I made strenuous efforts to see the best of it. The Prado (National Gallery of Spain) is the best known, and we visited it first. We only had an hour and a half there (and John had another half-hour later in the week), but it was enough.

If I say the Prado was slightly disappointing, it is only by reference to my expectations; the gallery has a formidable reputation which no doubt, to an art expert, is fully deserved. But there are an awful lot of religious paintings on show: Annunciations, Nativities, Flights to Egypt, Crucifixions, Resurrections, Ascensions. After a while it becomes a bit difficult to appreciate their individual merits. I did however come away with a better idea of why Velasquez is considered such a great master – the only previous exhibition of his work that I had seen, in London a couple of years ago, had left me unconvinced. There are also a large number of Goyas, which seemed to me to have more life than most of the paintings around them. In fact there were Goyas to be seen in many places that we visited, and John searched them out assiduously.

Of all the paintings in the Prado, the one I admired the most was not Spanish at all; it was Hieronymus Bosch’s triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights.

Bosch clearly had a peculiar and hyperactive imagination, but the triptych is undeniably fascinating, and it drew a crowd. (Most of the Prado, though busy, did not seem crowded; this was an exception.) It is not just the extraordinary subject matter but the vivid colours that stand out. Many of the older paintings we saw in the Prado and elsewhere have clearly faded, in particular the green pigments, but the Garden of Delights still looks as if Bosch had painted it yesterday. Which indeed he might have done, such is its timelessly surreal quality.

The second gallery we visited was the Reina Sofia, which houses modern paintings, mostly by Spanish artists, most notably by Picasso. Once we had solved the mysteries of the gallery’s layout – in most of the galleries we visited, we found the signage not visitor-friendly, let alone to foreign visitors – we enjoyed its exhibition quite a lot. The star painting on display there is Picasso’s Guernica, and it is currently featured as the climax of a long series of his paintings.

Whatever you may think of Picasso, Guernica is a stunning piece of work. It is a perfect fit of style to subject, almost as if Picasso’s entire development as an artist had been heading towards this one painting. The display panels noted that Picasso himself did not consider it his finest work, preferring The Three Dancers, which is also at the Reina Sofia. And Guernica is certainly not a likeable painting, nor is it meant to be. But it is, in the proper meanings, awesome, both for its content and for its mastery. I am very glad to have seen it.

Also at the Reina Sofia, once we had found them, were several paintings by two other Spanish 20th century masters, Joan Miró and Salvador Dali. We saw a large exhibition of Miró at the Tate Modern a few years ago, and he seemed to me to be a very uneven painter. I liked best his early paintings and the Constellations series, and there were some related to each of these at the Reina Sofia, but later in his life, when he was most famous, I think his inspiration faltered, and some of his latest work “innovates” in a lazy if not cynical way. If we return to Barcelona later his year, as we may, we will have the chance to visit the Miró Gallery and my impression of his work will be put to the test.

As for Dali, I’m sure I remember reading criticism that he can’t draw, but on this evidence that is quite false. The Reina Sofia has a couple of his early, orthodox paintings, which are no masterpieces but perfectly adequate and (to my untutored eye) well drawn; but of course it is his surrealist pieces which most catch the imagination. The gallery had several of these, all of them startling, thought-provoking and in some cases quite menacing. Well worth the effort to see them.

What I did think, seeing other Spanish artists’ work alongside Picasso, Miró and Dali, was how difficult it must be to be influenced by an artistic innovator, as all three clearly were, without devolving into imitation. In particular the pictures placed alongside Picasso’s seemed derivative without adding much that was original.

The Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, which we visited third, is simply stunning. There is an excellent website which I believe shows all their paintings: I recommend browsing first through the masterpieces (www.museothyssen.org/en/collection/masterpieces) and exploring further from there. But of course nothing beats seeing the original pictures. Unlike the Reina Sofia and, to a certain extent, the Prado, this is a truly international collection, extending from the fourteenth to the mid-twentieth century, and there is scarcely a dud piece on display. I even enjoyed the very early paintings, which usually leave me cold. Look for instance at the Portrait of Giovanna Tornabuoni (c.1490) which the gallery uses in its own publicity material. It is a stunning picture.

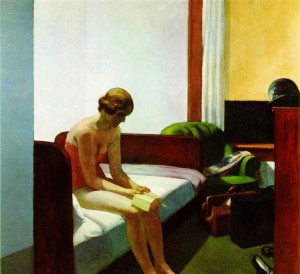

John and I spent more than four hours at the Thyssen and I am sure we could happily have spent longer. The family whose collection this was, before it was sold to the nation in 1993 (for $350 million, which was a bargain), had tastes which were both eclectic and acute. There are three floors, sixty-odd rooms in all, simply and logically laid out, with all the paintings clearly labelled and dated, so you can follow the development of the art of painting. One notable feature is the inclusion of several 19th century American works, mostly landscapes, not quite masterpieces but some of them very good indeed. I shall look out now for other pictures by Frederick Edwin Church and Martin Johnson Heade, of whom I had not previously heard. There are also good selections of both Impressionist and Expressionist works which I particularly admired. However, if I were told I could take away and keep one painting from the entire collection, I think it would be Edward Hopper’s Hotel Room, simple in style yet full of significance and feeling.

Our final visit, on our last day in Madrid, was to the Museo Lázaro Galdiano, which is in the exclusive Salamanca district, a mile or so away from the other museums and galleries. By this time my feet were very sore from an excess of walking and standing around, so my patience for painting and art had ebbed away a little; and it was also the hottest day of the week. So perhaps my judgement is slightly clouded. But I did find this the least satisfactory of our visits. The Lázaro Galdiano is a legacy to the nation from an ultra-wealthy collector; but Lázaro’s taste in artwork does not seem to have been entirely reliable. Some of the pictures are good (although religious themes are dominant) but many seem more the work of artisans than artists.

Still, the gallery, housed in Lázaro’s own mansion which he had specially built to show off his treasures, has its points. It includes Goya’s wonderfully grotesque The Witches’ Sabbath, Bosch’s St John the Baptist and a couple of paintings by the German Lucas Cranach which stand in interesting contrast to the collection around them. There are also some splendid pieces of inlaid furniture and a large collection of jewellery, silverware and ceramics.

Most of the ceilings are painted too, which has always seemed to me a dubious endeavour as you really have to crane your neck to see them at all and, without lying on your back, are unlikely ever to take in all the detail. As John said, living in the house must have been quite stressful, since one slip on the polished floor (perhaps while straining to see the ceiling) could easily bring down and damage some priceless painting or other treasure. But perhaps if I were to make another visit, when my feet were less painful, I would enjoy this gallery more.

——————–

Madrid

18 June 2017

John and I have just returned from a week’s holiday in Madrid with David, Sue and some of their friends from England. David had rented an apartment for us in the Retiro district, not far from the Atocha main line railway station and the tourist heart of Madrid where most of the museums and galleries are located.

It was a good holiday and we were very pleased to see David and Sue again, especially Sue, who shuns the use of Facetime to talk to us from their home in Australia. I don’t think we had seen her since we were last in Australia, more than three years ago; but she looks just the same, though more harassed by her work than ever. And we were very pleased to have the chance to explore Madrid. Our only previous visit to Spain was to Barcelona, in September 2014, and that was only for a few days.

But it was hot, very hot. And dry, and dusty, but mostly just hot. Afternoon temperatures approached, and on our final afternoon exceeded, 40º (that’s 104º in old money). Even for Madrid this was a bit of a heatwave, more like what they expect in mid-August than early June. According to online sources the average high temperature for Madrid in June is 29º, hot but not scorching, and the average rainfall for the month is 3 cm, with six days when rain falls. We didn’t get any of that, and there were times when, holiday or no, I thought a bit of rain would be a welcome relief.

On our first arrival, and again the following day, Sue (who had already been in Madrid for a few days) took us walking through the old city to see the principal sights: churches, squares (the Plaza Mayor and the Puerta del Sol, though the latter has been horribly disfigured by a massive Netflix poster), palaces and parks. It was an energetic introduction, and set the tone for the holiday: most of the places we visited were easier reached on foot than any other way. But I became progressively more footsore and weary.

Not surprisingly John and I spent a good deal of our time in the galleries and museums, which are air conditioned and more comfortable (how in the world did they manage before air conditioning was invented?), though no less tiring. I will write separately about our visits to the galleries, which we much enjoyed. After our first full day, when we all visited the Prado (National Gallery) together, John and I followed our own course, meeting up with the others for evening meals. Evidently our appetite for art is greater than the Australians’.

Meals were interesting. John and I found a little cafe nearby where we ate a small breakfast of croissant with ham and cheese, orange juice and coffee, or in John’s case tea. John doesn’t really like coffee, but some of the tea he received in various places was a bit odd. On one occasion the teabag arrived immersed in hot milk, with no water. On another he was given what may have been green tea or mint tea with milk. Eventually he bought some teabags and heated water for tea using the microwave in the apartment, as there was no kettle; I’m not sure this produced any better results. He didn’t get a recognisable cup of tea anywhere until Madrid Airport on the way home, but he kept trying.

John and I usually had no more than a snack for lunch, often in a museum cafe (I can recommend the one at the Archaeological Museum). One day David and the others had a set-menu lunch at a restaurant and were effusive afterwards in its praise; but my appetite all week was unusually small, perhaps because of the heat, and anyway we didn’t want to sit around eating and gossiping for 90 minutes while there was art waiting to be seen.

For our evening meals we tried a succession of cafe-restaurants in the heart of Madrid, where we could indulge ourselves in tapas. If I had been hungrier I might have found this a bit frustrating, as David and his friends regularly ordered two or three fish dishes which I couldn’t eat, being allergic to fish and shellfish. Apparently the octopus was consistently good. However, there was sufficient variety in tortillas, patatas bravas, Iberico ham and Padron peppers to keep me happy.

Apart from galleries and museums, we also visited the Palacio Real (Royal Palace) and several of the city’s fine churches. The opulence on display, not just in the palace but in the cathedrals and churches, is extraordinary, and reveals quite a lot about Spanish history, in which the Catholic Church has played a prominent part. I do understand the desire to glorify God, but find it hard to understand how the Church could reconcile such extravagant decoration with the plight of poor people in its care. The gold and silver treasures should were no doubt a joy to the Church when they should have been an embarrassment.

I don’t believe the Catholic Church wields the same power in Spain that it once did (though without reading the language, or staying for longer, it’s hard to be sure about this). But the gap between rich and poor is still wide, and visible. Everywhere we went in and around Madrid were signs of new building, especially infrastructure: a splendid new airport which knocks spots off Heathrow or Gatwick; new motorways – the one from the airport to the city centre is like one long spaghetti junction; new high-speed trains, and a suburban and Metro network to match Paris; museums and galleries which are well kept and curated. All this development seems to have occurred since the death of Franco and Spain’s accession to the EU, and much of it has been done with EU assistance.

But there is also visible poverty, with street vendors scratching a living and outright beggars haunting the cafes. Sue had her wallet stolen by one such; she was only distracted for a moment, and discovered the loss later. Spain has received its share of refugees, more generously than some European countries, but some of this poverty is clearly home-grown. The police and the cafe proprietors seemed remarkably tolerant. Either they fear what would happen if there was a crackdown or, as I suspect, the sight of beggars is nothing new.

Perhaps one of our final museum visits helps to explain this, or at least put it in context. John and I spent most of one day at the Archaeological Museum; it was perhaps the best visit that we made, and certainly the most enlightening. The Museum was fully renovated only a couple of years ago and is now fitted out with the best lighting and multimedia displays I have seen. The main exhibition tells the story of the Iberian peninsula straightforwardly and without condescension, and thus puts the artifacts on display, many beautiful and fascinating objects, into their proper context. Spain, it seems, has for centuries received waves of immigrants, colonists or outright invaders, each of whom have left their mark on its culture, with different influences predominant in different areas. I had never properly appreciated this, and now want to seek out a good history in English to fill out what the exhibition started to tell me.

John and I spent over half our time on the ground floor, with the displays and interpretations leading up to when the Romans defeated the Carthaginians in Spain, thus arguably setting the whole direction of Western civilisation. We didn’t exactly rush through the first floor, but we certainly skimped a bit, through the whole period of Roman occupation – for which there is a treasury of archaeological evidence – up to conquest by the Visigoths and then by the forces of Islam. Towards the end of his floor were the exhibits which I shall remember the most clearly, six complete or near-complete Roman mosaics which had somehow been lifted from their original sites and placed intact in the Museum. We didn’t have time for the second floor, which apparently continues the story of Spain almost to the present day and also has a free-standing exhibition about Egypt.

I now understand why the city puts so much effort and takes so much pride in the Museum. If we ever go back to Madrid, this will probably be the first place we visit. If you ever go there, you should do the same.

——————–

General Election

7 June 2017

Tomorrow (as I write this) will be Theresa May’s General Election. We didn’t need one, but she called it anyway. The opportunity to beat up a Labour Party which appeared to be in terminal crisis was too good to miss.

The idea which she put about that her intention was to strengthen her hand in Brexit negotiations was either deluded or a flat-out lie. I hope it was just deluded. But in any event it has backfired. It matters not to the EU whether the British Government with which it negotiates has a Parliamentary majority of 20 or 120. But it does matter that Mrs May has been shown to be weak, to turn tail when the going gets rough: making commitments on the hoof, reversing her own manifesto policy on the “dementia tax,” fighting shy of public appearances when possible and wobbly under pressure, illiterate on the economy and out of step with her own Ministerial colleagues, including her Chancellor and Foreign Secretary. All this will be stored up in the EU negotiators’ minds. And it was all unnecessary.

Her best hope – and, despite everything, it will probably carry her to victory – is that enough electors, given the appalling choice between her and Jeremy Corbyn, will stick with the devil they know. Corbyn has fought a brilliant campaign, but has been in most difficulty when his own past has caught up with him. He is just too exposed on the company he has previously kept, and he has not been adequately prepared for the questions that he must have known would come his way. In the last couple of days he has been forthright in his unequivocal condemnation of the terror attacks in Manchester and London, and effective in exposing Theresa May’s weakness on police numbers and financing. But it has been too little, too late.

In fact I have a good deal of sympathy with Corbyn’s view that eventually it is necessary to talk to people with whom you profoundly disagree. That is, after all, what the Major and Blair governments both did, behind the scenes, with the IRA. But they did it quietly, and in the meanwhile did not water down their public condemnation of IRA atrocities. Corbyn did not, and it has come back to haunt him.

Corbyn has three reasons for hope. The first is that he has stirred up enough enthusiasm among young voters for them to turn out and vote for him. I suspect that he has not, or at best that the effect will be patchy. The second is that the voting public has grown wise to, and weary of, the campaign of fear which the Conservatives have pursued. Some of the tendentious misrepresentation and outright nonsense which the Daily Mail has produced has been disgraceful: so over-the-top that it may, just, backfire. During last year’s referendum campaign too much of the Remainers’ argument was based on fear, and voters were not impressed. It might happen again. If the Daily Mail’s worse excesses proved to be counter-productive it would be poetic justice.

The third reason is that voters are smart, smart enough to vote tactically when it may make a difference. The Liberal Democrats have been faring badly in national opinion polls, but there are half a dozen seats where they lost narrowly to the Conservatives in 2015 that they may be able to reclaim if enough Labour supporters switch their votes. The same may be true, in reverse, elsewhere. It is a shame that the opposition parties have been unable to advocate tactical switching more openly, but the Conservatives’ warnings about a “coalition of chaos” put paid to that, as they were no doubt intended to do. Many among the generation of Labour politicians for whom I worked, the Prescotts and Blunketts, disliked the Liberals intensely and would have opposed any kind of collaboration; but that generation has now gone. However, the voters may still see the possibility even when the politicians deny it.

I shall be voting Liberal Democrat here, as I have in every national election since I came to live in Oxted. Labour has no chance here. Indeed it would be a monumental upset if anyone other than the Conservatives ever won in South East Surrey, even now with an MP seeking re-election who is one of Cameron’s carpet-baggers, rarely seen or active in the constituency. (By contrast his predecessor, Peter Ainsworth, was well-known and liked across the district.) It is a continuing disgrace that our electoral system effectively disenfranchises millions of people like me, living in “safe” constituencies where our voices can never be heard.

Unfortunately, at this time of opportunity which surely would have been seized by David Steel, Paddy Ashdown or even Nick Clegg, the LibDems are currently led by a lightweight. Tim Farron’s constituency includes our house in Cark (though we have no voting rights there) and I know that he is an excellent local MP. He was also by all accounts a good President of the LibDems, where his engaging enthusiasm and people skills were put to good use. But as leader, even against lacklustre May and vulnerable Corbyn, he comes up short. If the LibDems gain a handful of seats, and they might, it will be because their candidates were first class, not their leader.

I have not always voted Liberal. When I was first able to vote, while I was at university in the mid-1970s, I favoured the Conservatives: I was pro-European, as the Tories were at that time, and I disliked the company then being kept by Labour (Arthur Scargill and his associates). Oxford at the time was a two-way marginal; the Liberals were irrelevant. In 1983, living in London, I spoiled my vote, out of equal disttrust (for different reasons) for both Thatcher and Foot. In 1987, though, I supported the Lib/SD Alliance candidate, and have stuck with the Liberals ever since. This is probably more because I am a cautious centrist than out of any great conviction. I do believe Nick Clegg gets less credit than he deserves for his share in Cameron’s coalition, keeping the wilder excesses of the Tory right at bay, as we may find out to our cost in the next five years. But Clegg did not do as well as he might, in particular failing to block Lansley’s NHS reforms as he could have done, and that is a black mark against him.

I shall cast my vote first thing tomorrow morning, but shall be out of the country on election night, unable to follow the TV coverage as I usually do. I still remember the excitement in 1992 when the Conservatives held Basildon, indicating that Major had held on against Kinnock, and in 1997 when Michael Portillo lost his seat in Blair’s first landslide. (What would we give for Portillo as PM today?) I may, however, find it hard to tear myself away from my iPad, especially if the results turn out not to be a procession.

Making predictions the day beforehand, when most of my readers will probably know the outcome, is a bit of a mug’s game. But for what it’s worth: I think May will win, but with a majority some way short of three figures. I think there will be more than the usual number of surprises, in pockets where Corbyn has galvanised the youth vote, but also that Labour may struggle to keep hold of some traditional safe seats where UKIP voters in 2015 revert not to Labour but to the Tories. I think (or maybe this is merely hope) that the LibDems will achieve a modest increase by regaining a handful of seats narrowly lost in 2015, especially in and around London where Remainers are strongest.

What I would like to see is May returned with a majority that has barely changed. (Hoping for her not to win at all is unrealistic.) That would shake her complacency and stall her bulldozer tendencies, and help to secure some of our more liberal institutions like the BBC and the NHS. What I fear – and this is a real fear, because it could easily happen – is that May and the Tories will be strengthened, and their right wing emboldened. I also fear that Corbyn will do just well enough (against rock-bottom expectations) to cling on to his leadership, condemning us to another five years without effective opposition. And I fear that the LibDems will stagnate, or even decline. My only solace is that David, Sue and their family have survived well enough in Australia despite a series of governments and Prime Ministers more crass than even Theresa May is likely to prove. We learn to cope; life goes on.

——————–

Eli and Arun’s wedding

5 June 2017

I went on Saturday to the wedding of Michelle’s daughter Eli. The ceremony was secular and took place in the Porchester Hall, in London’s Bayswater district. I had a bit of difficulty getting there, as half of London’s tube network seemed to be out of service for planned maintenance work – both of my first two planned routes turned out not to be possible, and I was glad I had allowed plenty of time. Fortunately the weather was bright (there was a drop of rain in the early evening, I believe) as it was a fair walk from the station to the Hall and I travelled light, without coat or hat. For once I wasn’t caught out by this temerity.

The wedding was a splendid occasion, impeccably planned by Eli and her new husband Arun, with a fair amount of assistance beforehand from Michelle (who had, among other things, baked and iced a gorgeous three-tier cake: there was a fruit cake tier, a carrot cake tier and a madeira cake tier, which I can testify was excellent) and no doubt many other helpers. There were something like 200 people present for the ceremony and more arrived afterwards, which made it comfortably the largest such occasion I have ever attended.

The wedding took place in three Acts. I use the term advisedly; Eli and Arun used it themselves on the various invitations, the order of service, the menus and no doubt elsewhere, and the theme was carried through. For instance the 24 tables for the reception – each with eight or more people around it – were designated, on the table and on the seating plan, by tickets for some past musical or theatrical event. Round each table were groups of friends or family with some connection, so your neighbours at table were people you knew and could comfortably talk to. My table was a group of Michelle’s friends, and our ticket was for a concert at St John’s Smith Square, where many of us have met in the past. There were also tables for friends from King’s College London, where Eli studied music; for Boosey and Hawkes, the music publishers, where she used to work; for the BBC, her current employers; and no doubt others with similar connections which I didn’t spot. The whole occasion was planned with this mixture of style and thoughtfulness which is really hard to beat.

But I am getting ahead of myself. The first Act was the ceremony itself, performed by the deputy Westminster Registrar. (I imagine that the Registrar him- or herself only turns out for royalty or celebrities, and Eli and Arun are not quite that, yet.) She had a fairly quiet voice, but I had cunningly stationed myself in the third row back, not to miss anything. I was interested by how closely the ceremony followed the pattern of a typical CofE wedding, stripped of all the religious trappings. So there were no hymns, prayers or sermon and no references to God, but there were the familiar formal pause for objections, the solemn statement by the Registrar about the purpose and commitment of marriage, vows repeated separately by husband and wife, the exchange of rings, and a wholehearted round of cheers and applause when they kissed.

During the ceremony there were a couple of readings. Michelle read Wendy Cope’s poem The Orange (www.poemhunter.com/poem/the-orange-7) which I thought was an inspired choice, whoever made it: a simple poem about sharing, love and the joy of everyday life. While the register was being signed, an a cappella choir made up of Eli’s and Arun’s musical friends performed La Rose Complète by Morten Lauridsen (www.youtube.com/watch?v=LUeBmYfoiYw) and an arrangement of Stevie Wonder’s song Golden Lady. To be honest the Stevie Wonder left me unmoved and the Lauridsen, though an excellent (and highly à propos) piece in itself, sounded exactly like all of Lauridsen’s music I have ever heard. But here and now that didn’t matter, and both songs were beautifully performed.

After Act 1 was complete there was an intermission while the Hall was re-set for the evening and we all went out into the park across the road for photographs. There were no fewer than three photographers, but the guy who took the big group photos had brought with him a tall stepladder, and for such a large group he certainly needed it. Here too the planning and forethought were in evidence. He was working from a list of photos to be taken, and the group pictures came early, so we didn’t all have to wait around for instructions, but could wander off, talk among ourselves or stay to watch, as the mood took us.

Eli looked stunning in her oyster-white layered dress sewn with hundreds of crystal gems, and Arun was no less dashing in a beautiful teal-coloured turban. Teal seems to have been a theme colour: all the men in the wedding party wore teal ties. The bridesmaids, five of them including Eli’s elder sister Jess, all wore the same dark blue but in different styles (so I’m told; I can’t say I noticed this for myself) and with sashes in different colours. Arun’s two best men wore turbans of the same dark blue, two really big guys whose height was accentuated by the turbans, like London bobbies. They were really hard to miss.

Act 2 was the reception. The food was Indian style, with poppadoms and chutney, a mild chicken curry with spiced vegetables, rice and naan bread, and Indian mango ice cream. I had taken the offer of an English alternative as I was a bit worried (though, as I quickly realised, I absolutely needn’t have been) about the risk of hidden ingredients, nuts or coconut, to which I am allergic. Nothing spoils an occasion like this more than having to deal with a guest who is taken ill. My dinner too was fine, with plain chicken and roasted peppers. An inspired choice, as I love roasted peppers. Most of the guests were braver than I; I was told that Jess, who likes her food severely plain, and I were the only two hold-outs. There were several speeches, all mercifully brief, which from where I was sitting I couldn’t hear too well but seemed to include the usual roll of thanks, acknowledgements to those who couldn’t be present, and a leavening of humour.

Act 3 was music and dancing. The part of the Hall where the ceremony was held had been cleared, so we could stay at our tables or get up to dance. Though staying at our tables was a moot choice, as the live band, who were just as excellent as the earlier music, were extremely loud. They had three brass players, two keyboard players, a drummer, a bassist and a lead singer who occasionally beat a tambourine, and the music they played was what I think of, possibly quite wrongly, as funk, though with a jazz fusion element to it. The brass players were really put through their paces. I danced quite a lot (which I really had not expected to do), first with Michelle’s friend Janet and then with Michelle herself. I’d feared that there would be ballroom dancing and Michelle, who has been going to classes, would make me dance with her, though it’s 35 years or more since I did my ballroom dancing. But this was not a ballroom occasion at all. I looked out for Jess in case she wanted to dance too, but she had disappeared. I found out later that she really didn’t care for the noise and had taken herself off to a quiet room backstage which I didn’t know about.

When the live band was done there was a disco, and after about twenty minutes they switched to music I can’t categorise: loud, with droney Indian-style vocals, a mixture of Western and Indian instruments, and a rapid Western-style beat. I stayed just long enough to see a kind of celebratory dance by Arun: the women of his family, apparently spontaneously and with some interlopers, formed a circle while he danced in a kind of furious joyfulness, joined from time to time by one from the women in the circle, and culminating in Arun being lifted on the shoulders of his best men while he was still swaying and dancing. It was a physical expression of joy and – I don’t know, exaltation? – like nothing I’ve ever seen, and curiously moving.

I’d have to say, though, that this music did nothing for me at all, and anyway it was time to go home. (Not too soon; either; I caught the last East Grinstead train from Victoria that evening.) I thought I would pay in the morning for all the unaccustomed physical effort of dancing that much, but in fact I’m fine. Altogether it was a great day.